Introduction

Maintaining and increasing spectator satisfaction is an important goal in stadium management (Hock, Ringle, and Sarstedt, 2010). This need is more profound in multifunctional stadia that cater to different customer needs. Therefore, the stadium management process needs to cater to the needs of a wide spectrum of customers who span across business and leisure sectors. To understand the best principles that underlie effective sports venue and event management techniques, it is, first, important to understand the key management sectors that inform the discipline. Financial management, policy development, marketing, human resource management, operations management, event planning, and governance models are some management factors that underlie stadium management processes. In two sections, this paper analyses four management aspects of the above list. The first section investigates and explains the role of financial management, human resource management, policy development and marketing in sports venue management. Based on this background, the second part of the paper focuses on financial management as an important aspect of stadium management. Through a case study approach, the second section of the paper also compares the financial management techniques of two stadia – Etihad Stadium, in Melbourne, Australia, and the London-based Emirates Stadium.

Management Characteristics of Venue Operations and Management

Financial Management

Good financial management is an important aspect of sports and event management. It involves several aspects of operations, including financial reviews, funds management and policy formulation processes (Schwarz, Hall, and Shibli, 2010). Many management boards of sports venues/stadia appoint a financial director to undertake these financial responsibilities. They understand that their tasks are important to the survival of other aspects of stadium management, such as strategic planning and accountability. Corporate governance and effective risk management roles also fall within the same spectrum of importance. Financial management responsibilities, in sports venue management, involve financial reporting, asset management, petty cash management, and the budget formulation process (Rich, 2000). Some management bodies may expand the scope of these roles to include other duties assigned by financial directors. Nonetheless, all these financial management functions need to align with existing corporate laws. These laws may vary depending on the country of origin.

Different researchers have introduced varied management models for guiding financial management services in different stadia. One common model is the “private” management framework, which highlights the need to manage stadia as private entities (Rich, 2000). Many European stadia use this model to manage their facilities. For example, football clubs operate as private corporate entities that own and manage stadia. Manchester United, Chelsea, and Arsenal are some notable English football clubs that manage their facilities using this model. Financial management happens at the behest of the club and (almost) all the revenue collected goes to the club. This model exemplifies the need to operate sports facilities as profit-making entities. The public management framework is a “contradicting” model, which does not focus on profit-maximisation as its main goal. Instead, it mainly focuses on promoting public welfare (Schwarz et al., 2010). Many “welfare” countries use this model to guide their financial operations because they believe that giving private entities the power to manage a sports facility is tantamount to ignoring the interest of minority groups. The biggest drawback of this financial management model is the lack of innovation and efficiency when managing such sports facilities (Rich, 2000). Comparatively, the private management model adopts a more efficient framework for managing sports facilities.

Human Resource Management

Chelladurai (2006) says people are the most important element in sports management because other aspects of the sports industry would not operate without them. Moreover, human resource operations affect other aspects of operations management, such as financial management, marketing, and policy development. Therefore, human resource plays an important role in sports stadium management. Its influence affects top-level management, which captures decision-making and resource distribution levels. Arguably, this is the highest and most influential level in sports management. Relative to this assertion, some researchers believe the most important aspect of human resource management, in the sports industry, is the management of sports participants. For example, Chelladurai (2006) believes that all athletes make meaning of sports facilities by attracting people and turning different attributes of a stadium into resources.

Similarly, digital scoreboards are only useful when people operate them and when they inform the spectators of the prevailing scores in a game. Therefore, without human resource, sports facilities would remain like that. In this regard, Chelladurai (2006) says many sports stadia are resources when athletes compete in them and attract crowds of people who, in turn, generate revenue. Therefore, human resource management is more important than other aspects of facility management. This way, it requires a different type of attention from other management factors.

Three issues emerge as important concepts of human resource management in sports and event management. The first issue is profitability (Rich, 2000). Stated differently, if the directors of sports facilities manage their human resource effectively, they could easily increase their profitability. The second issue is the role of value systems in influencing employee practices and customer responses to align with employee inputs. The third concern involves understanding the link between sports facilities and the communities that support those (Rich, 2000). Here, sports facilities should contribute to community development. Therefore, managers need to understand how employees and sports participants support this goal.

Facility Marketing Management

Although the sports industry is an independent discipline, it mainly relies on marketing to realise its success (Higham, 2007). Furthermore, many sporting events depend on spectator involvement. In this regard, it is difficult to attract huge crowds without marketing these events. The commercial potential for sports has generated interest from corporate bodies, the tourism sector, governments and other stakeholders. For example, many spectators from around the world flocked Brazil in the recently ended 2014 world cup. They needed places to stay, food to eat, and transport to move across different sports stadia (among other basic services). The government, hoteliers, security agencies, transport companies and other stakeholders had to participate in the event to provide these goods and services. However, for their activities to yield good results, they had to formulate an effective marketing campaign. This same logic underlies the management of sports stadia. People need to know the venue of sports events, their seat numbers, how to get to the sports venue, and such issues.

The above needs stem within the main purpose of facility marketing management – profit maximisation. Practically, this means that the main purpose of facility marketing management is to increase spectator numbers and attract more corporate sponsorship deals (Rich, 2000). Different stadia have gone about these roles differently. For example, in the USA, the management of New Yankee Stadium attracted more spectators by increasing the width of their stadium seats, from 18-22 inches to 19-24 inches (Higham, 2007). While this strategy may be an effective approach of increasing spectator numbers, many scholars have questioned the logic used by some sports facility managers to increase ticket sales (Higham, 2007). They say that many sports management literature, today, focus on adhering to “best practices” in selling tickets. However, there is a debate regarding “good” and “bad” practices (Higham, 2007). It stems from the failure of some practices to work in some countries and succeeding in others. Based on this concern, there is a strong need to use proper research (about the country involved) to formulate facility-marketing practices. Higham (2007) says there is a lot of potentials for marketers to develop stadia as sports-based visitor attractions. However, they can only harness this potential if they understand the main pillars of facility marketing management (Team Sports Marketing, 2014).

Policy Development

Development policies outline the framework for stadium management. They show the rules and policies that shape institutional activities and employee conduct. This framework also explains how spectators should behave, the operational hours of a stadium, and the relationship between the sports facility and the community. Rich (2000) sums these roles by saying the policy framework should implement the strategic aims of the management committee (or the organisation that manages the stadium). The policy framework should provide a ready answer for any question that arises about an aspect of stadium management (Rich, 2000). Therefore, all stakeholders involved in stadium management have a framework for broad decision implementation.

The DIY Committee (2014) highlights the need to understand that the policy development process is only subject to national laws and the internal views of stakeholders involved in stadium management. In some jurisdictions, the historical value of an organisation and service management systems also shape the policy development process (DIY Committee, 2014). The effective adoption of a policy framework protects organisations and stadia management committees from management pitfalls. For example, the DIY Committee (2014) says such frameworks prevent these teams from unethical business practices, administration inconsistencies and inequities in management practices. This way, they enjoy continuity.

Although different bodies that manage stadia pursue different policy frameworks, the DIY Committee (2014) says they need to make sure that their policy frameworks align with their organisational goals, meet their legal responsibilities and undergo effective adoption. To make sure companies meet these criteria, the management committee needs to delegate all levels of employees with different types of responsibilities. Overall, in terms of managing stadia, it is important for management committees to ensure that the policy framework helps the organisation to achieve its goals and objectives. Management companies that adopt effective policy management programs benefit from several advantages, including increased consistency, improved reliability, and enhanced effectiveness. Similarly, they could capture whatever has evolved as “best practice” and apply the same in stadium management procedures. Since this program acts as a framework that includes all types of employees, all workers can easily learn about management practices and improve their productivity in the same regard.

Stadium Comparison – Case Study

This section of the paper focuses on the financial management plan as an important aspect of the sports venue management. It uses it as the main comparative platform for assessing the performance and management practices of the Etihad Stadium (Melbourne, Australia) and Emirates Stadium (London, England). However, before delving into the details of this analysis, it is important to understand the purpose, history and current operations of each stadium.

Etihad Stadium (Melbourne, Australia)

Purpose

Etihad Stadium is a multipurpose sports facility, which receives its funds from the Middle East-based airline, Etihad Airways. The diagram below shows its structure.

The Australian Stadiums and Sports (2014) say Etihad Stadium services the needs of about 4,000,000 spectators. Moreover, it can hold up to 55,000 fans at once (Australian Stadiums and Sports, 2014). Besides hosting major sports events in the country, the sports facility also acts as a conferencing and exhibition facility. This is why it has hosted many product launches and corporate dinners for different types of Australian clients (Australian Stadiums and Sports, 2014). Besides hosting corporate events, the sports facility also hosts different kinds of games. For example, it has hosted rugby, cricket and football matches. Furthermore, different entertainers, such as U2, and Robbie Williams have used the facility as an entertainment venue (Australian Stadiums and Sports, 2014).

History

Etihad Stadium is at the heart of Melbourne’s Dockland’s precinct. In the past (before the government branded it as Etihad Stadium), people knew the sports facility as Telstra Dome. Similarly, before it acquired the “Telstra Dome” name, another right naming deal made sure people referred to the stadium as the Colonial Stadium. Today, Etihad Stadium is a popular sports venue because it is the only roofed sports facility in its locality.

Current Operations

Currently, the management of Etihad Stadium is comprised of investment firms and owners of superannuation funds (Stensholt, 2014). It does not have any affiliation with a major football, or sports group, in Australia because it rents out its facilities to different types of clients.

Emirates Stadium (London, UK)

Purpose

Similar to Etihad stadium, in Melbourne, Australia, Emirates Stadium is also a multipurpose sports facility. For example, besides hosting football matches, the sports facility also acts as a venue for music concerts. Similarly, Rosner & Shropshire (2011) say the sports facility hosts conferences for different corporate groups. Infamously, the Emirates stadium has a politically significant relationship to the UK-French relations. This is why it hosted a summit between the UK prime minister and the French President in 2008 (Rosner & Shropshire, 2011). Nonetheless, it hosts football matches as the main activity. Emirates stadium can hold up to 60,000 fans at once. However, this number can increase to about 70,000 when it hosts a musical concert (Rosner & Shropshire, 2011).

History

The history of Emirates Stadium stems from the 1989 Hillsborough disaster, which saw dozens of fans lose their lives. The incident created special attention to spectator safety in English football stadia. It also led to major changes in the stadium’s design. These events further created the impetus to modernise the stadium and enhance the proactive involvement of Arsenal in the facility’s management. This is why many people associate the sports facility with the English football club. Therefore, Arsenal owns and maintains the London-based sports facility, as its home stadium. The facility is among the biggest sports centres in the UK.

Current Operations

Currently, Arsenal football club manages most aspects of Emirate’s operations. The stadium has a strong affiliation to the club and, besides acting a key revenue generation facility, it stands out as an iconic piece of art in the English football scene.

Comparison of Financial Management Operations

Financial Performance

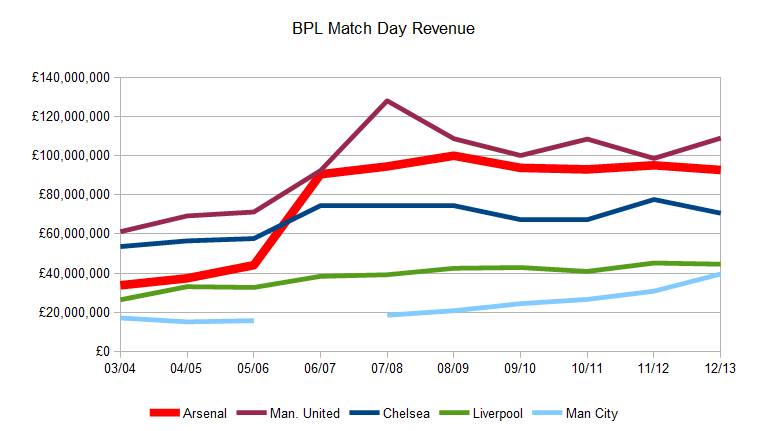

Etihad stadium uses a “private” financial model to manage its revenue and expenditure. Currently, Melbourne Stadium Limited manages the stadium’s operations (Stensholt, 2014). Arsenal uses the same model to manage the Emirates stadium. It does not receive government subsidies. Its “private” financial model has helped it maintain several years of profitability. Furthermore, this model has allowed the company to generate revenue through more innovative ways, like player transfers and corporate sponsorship arrangements. In 1999, this financial model accounted for about $50 million of the club’s revenue (Stensholt, 2014). Although this figure represents past financial transactions, it also highlights the club’s current “private” business model. The graph below shows that Arsenal is among the highest-earning football clubs in Europe (in terms of revenue collection)

Managers of Etihad Stadium also use the “private-owned” financial model to manage their finances. However, the stadium has not experienced the same positive financial outcomes that the Emirates stadium has reported. For example, recently, the stadium reported significant losses. It made a $17.3 million loss in 2012 (Stensholt, 2014). Compared to a $19.8 million loss in 2011, the stadium had slightly improved its financial performance. Interestingly, the stadium’s management reported this loss after experiencing an increase in revenue from $69.9 million, in 2011, to $72.5 million, in 2012 (Stensholt, 2014). Audits of the stadium’s assets affirm its poor financial performance. For example, during the above financial year, the stadium’s asset value decreased by $12 million (Stensholt, 2014). The value of the stadium’s licence to operate also decreased with the same margin. Today, the facility has a negative net asset of above $90 million (Stensholt, 2014).

Revenue Model

Unlike Emirates stadium, Etihad stadium gets most of its financial resources from loans. In fact, Stensholt (2014) says the stadium owes its creditors about $192 million. However, as highlighted above, both stadia have the same business model because they usually depend on one football club as the main tenant. For example, Etihad Stadium depends on the Australian Football League (AFL) as its main tenant, while the Emirates Stadium depends on the Arsenal football club. Although there are scanty details about the sponsorship deal between Etihad Airline and the management team of Etihad stadium, Stensholt (2014) says the naming deal is worth millions of dollars. In the agreement, the UAE-based airline secured the stadium’s naming rights until 2019 (Stensholt, 2014). This arrangement means that the airline will have sponsored the stadium for a decade (after completing the naming deal). This deal also means that Etihad Stadium gets money from Etihad Airways.

The management of the Emirates stadium (mainly) generates its revenue from sponsorship deals that involve big multinationals. For example, in 2000, the club generated more than $57million through a corporate sponsorship deal, which involved the Granada Media Group (Rosner & Shropshire, 2011). The deal allowed the latter entity to sell merchandise and exploit the potential for online viewership of matches that happened in the stadium. The internet-viewing project generated an extra $30 million for the club (Rosner & Shropshire, 2011). Similar to the management model of Etihad Stadium, Arsenal has also taken loans from banks to finance the stadium’s operations. For example, the club took loans from the Royal Bank of Scotland to expand its stadium’s seating capacity (Rosner & Shropshire, 2011). Lastly, since Arsenal has a strong support base, the club raises revenue through bond issues. For example, in 2003, the club issued bonds worth $4500 and $6000 to its supporters (Rosner & Shropshire, 2011). This strategy is a key part of its revenue model.

Expenditures

Unlike the financial management plan of Etihad Stadium, Emirates Stadium mixes the club’s expenditure with the stadium’s expenditure. Furthermore, its management team diverts some of its revenue to promote the “Arsenal” brand. Comparatively, Etihad stadium uses its revenue (mainly) to finance the stadium’s operations. Although the AFL club as its main tenant, the sports facility does not have a special corporate arrangement with the club to finance its activities.

Conclusion

This paper focuses on financial management, human resource management, policy development and marketing as important components of the sports venue management. Evidence points to the interrelations among the four components because no management aspect is isolated from one another. Nonetheless, this paper has focused on financial management and compared how Etihad Stadium’s financial management plans differ from similar plans by the Emirates stadium. The latter has high cash flow and enjoys an expansive source of revenue. Moreover, Emirates Stadium enjoys the support of Arsenal football club (which manages it) and its followers. In fact, this support provides it with revenue from bonds, as another revenue source. Although the names of both clubs have a Middle Eastern origin, their management structures differ. While the Arsenal club manages the Emirates stadium, a selected body of professionals manages Etihad stadium. However, this difference does not supersede the private financial model that both stadia share. Both stadia share this common management framework in their financial management models. However, their expenditures and revenue streams differ. This fact explains the numerous losses that Etihad stadium has reported in the past. Emirates Stadium has not reported such losses because of increased revenue collection and immense spectator support. Nonetheless, both entities are multipurpose sporting facilities that strive to improve the quality of services through prudent financial management techniques.

References

Australian Stadiums and Sports. (2014). Etihad Stadium. Web.

Chelladurai, P. (2006). Human Resource Management in Sport and Recreation. New York, NY: Human Kinetics.

DIY Committee. (2014). Policy development. Web,

Higham, J. (2007). Sport Tourism Destinations. London, UK: Routledge.

Hock, C., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2010). Management of Multi-Purpose Stadiums: Importance and Performance Measurement of Service Interfaces. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 14(2), 188-207.

Rich, W. (2000). The Economics and Politics of Sports Facilities. London, UK: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Rosner, S., & Shropshire, K. (2011). The Business of Sports. London, UK: Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

Schwarz, E., Hall, S., & Shibli, S. (2010). Sport Facility Operations Management. London, UK: Routledge.

Stensholt, J. (2014). Etihad stadium records $17.3m loss. Web.

Team Sports Marketing. (2014). Marketing Management. Web.

TGR. (2014). Arsenal Financial Analysis via Deloitte. Web.