Abstract

This dissertation aims to test the validity of the initially proposed thesis that the transforming essence of ‘global governance’, triggered by China’s intention to become its rightful agent, should be seen as indicative of the fact that it is specifically the Realist model of IR, which better than any other explains the discursive significance of geopolitical developments in today’s world. The study’s subject is the thematically relevant publications (conventional and web-based) that discuss different aspects of China’s continual affiliation with the concept of ‘global governance’. It is assumed that the proposed research project will deepen our understanding of what accounts for the practical implications of current trends in the arena of international politics.

The methodological approach to conducting the dissertation’s empirical phases is concerned with: a) obtaining the preliminary insights into the subject matter in question (Literature review), b) identifying/codifying the recurrent ‘clusters of meaning’ in the reviewed literature, and assessing the would-be obtained data within the framework of the Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). To make the process of codification more effective and less time-consuming, we decided in favor of using the OpenCode software.

The study concludes that the initially proposed thesis was thoroughly viable. There are indeed many reasons (backed by the conducted research) to think that China’s stance on ‘global governance’ is reflective of both: a) the process of this world becoming ‘multipolar’ once again, b) the fact that the agents of ‘global governance’ are driven by the clearly defined Realist agenda, on their part.

Introduction

One of the most notable aspects of today’s geopolitical situation in the world has to do with the fact that, as time goes on, a number of classical notions/concepts, concerned with the theory of international relations (IR), become either outdated or transformed to a degree of beginning to convey entirely new meaning. For example, the ongoing process of Globalisation has resulted in undermining the soundness of the notion of ‘national sovereignty’, which even today continues to represent the actual cornerstone of international law, as we know it – at least in the formal sense of this word.

The most contributing factor, in this respect, is that the mentioned process results in the gradual delegitimization of the idea that nation-states are in the position to exercise full control over the political and economic dynamics within the national borders. As one of the most ardent advocates of Globalisation, Ohmae (2005) pointed out, “The traditional centralized nation-state… is ill-equipped to play a meaningful role on the global stage” (p. 4).

This point of view is shared by another supporter of ‘global governance’, as the essentially anti-Westphalian undertaking, Weiss, “A narrow focus on states fails, even more obviously now than in the past, to capture the multifaceted nature of contemporary world politics” (2015 p. 403).

Therefore, it can be safely assumed that there were indeed many objective preconditions for the concept of ‘global governance’ (as such that implies the unification of legal, economic, and political rules/regulations across the planet) to be perceived increasingly viable through the 20th century’s late nineties and the first decade of the 21st century. After all, throughout the historical period in question, the U.S. (the West) has attained the undisputed geopolitical dominance on this planet – something that made such a hypothetical unification thoroughly realistic.

Nevertheless, the concept of ‘global governance’ is now itself undergoing a semiotic transformation, in the sense that more and more political scientists use it in conjunction with the notion of inter-state multilateralism. The reason for this is that it now becomes increasingly clear that it is not only too early to assume the sheer outdatedness of the traditional concept of ‘statehood’ but also that the dynamics in the domain of international politics continue to remain explicitly Realist – something that implies that ‘global governors’ cannot be unbiased, by definition.

As Forman and Segaar (2006) argued, “Many developing countries experience a real sense of futility when they are faced with… the unauthorized interventions by ad hoc coalitions of the willing, or, more generally, the overwhelming power and influence of wealthy, industrialized countries” (p. 211). This trend, of course, undermines the soundness of the idea that ‘global governance’ can be effectively exercised by non-state actors and that there must be some prominently defined ‘progressive’ subtleties to it. As a result, the concerned concept does not quite refer to what it used to, even as recent as a decade ago.

The recent rise of China, as a ‘regional power’ that is on the pathway of becoming a ‘superpower’, is fully consistent with the mentioned development. After all, this development did contribute rather substantially towards the process of this planet becoming increasingly ‘multipolar’, in the geopolitical sense of this word. Consequently, the concerned process results in prompting the Chinese government to believe that China is not so much of the ‘global governance’s’ subject, as it happened to be its actual agent.

As a result, the concept is being deprived of one of its main discursive attributes – the Eurocentric assumption that one of the foremost aims of ‘global governance’ is to ensure that just about every country remains strongly committed to the cause of protecting ‘human rights’. China’s decision to contribute actively towards addressing the most pressing global concerns naturally resulted in bringing about this development.

After all, it is not only that the Chinese government continues to refute Western claims about the violations of ‘human rights’ in China, but also the country’s governmental officials never hesitate to resort to the undiplomatically strong language while pointing out to these claims, as such that are meant to undermine the integrity of Chinese society from within. At the same time, however, today’s China is recognized as the thoroughly legitimate agent of ‘global governance’. As a result, political scientists around the world are now prompted to reassess the validity of the Western take on such governance – something that creates the objective preconditions for the concept in question to be seen increasingly divergent from the notion of Pax Americana.

As of today, there is no shortage of academic publications that establish a dialectical link between the mentioned semiotic transformation of the concept of ‘global governance’ and the fact that China’s economic/political influence in the world continues to increase. Because of it, we are in the position to gain quite a few preliminary insights into how both phenomena interrelate.

One of these insights has to do with the fact that it was named in the year 1995 that the high-ranking members of the Communist Party of China (CPC) began to denote the term ‘global governance’ as being thoroughly consistent with the country’s official ideology. While delivering his speech at the U.N. Conference in Melbourne in that year, Wang Yizhou used the term in reference to what he saw the Organisation’s increased role in preventing the escalation of armed conflicts on this planet (Wang & Rosenau 2009).

The available literature of relevance also makes it possible to identify the main difference between the Western conceptualization of ‘global governance’ and the Chinese one. Whereas, in the West, it is commonly assumed that the concept in question is synonymous with the notion of ‘enforced standardization’, the Chinese paradigm of this type of governance is based on an entirely different idea. That is, according to the Chinese, instead of trying to impose the universally applicable rules and regulations upon different countries, the ‘global governance’ agents should be concerned with establishing the objective prerequisites for the civilized reconciliation of the acute political, ideological, and economic tensions between nations.

However, China insists that under no circumstances should independent nations be coerced to reconsider the ways in which they go about taking full advantage of their endowment with statehood (Lai-Ha, Lee & Chan 2008). In fact, the Chinese have coined up their own term for the idea of global governing – hexie shijie (harmonious world). This term implies that, even though the establishment of the internationally recognized arbitration authorities is indeed crucial for the speedy and efficient resolution of territorial and economic disputes between different countries, these authorities should not be allowed to meddle in the internal affairs of the former.

There is yet another qualitative aspect to how the concept of ‘global governance’ is now perceived in China – the Chinese government never ceases stressing out that even though the so-called ‘Non-governmental organizations’ (NGOs) do contribute towards addressing the issues of global importance, they can never be considered independent players in the arena of international politics (Safdar 2011). Moreover, China insists that under no condition may ‘global governance’ impede the ability of nation-states to exercise sovereign authority. This, in turn, explains why China remains highly critical of the idea that the ‘protection of human rights’ should be incorporated into the conceptual paradigm of what this type of governance stands for.

Many authors also point out the fact that China never ceases to apply a continual effort into expanding the sphere of its geopolitical influence, which can be seen as indicative of the fact that the Chinese leadership tends to assess the concept’s discursive implications from the Realist (as opposed to Constructivist) perspective – something well consistent with the country’s Confucian legacy. After all, China’s conceptualization of ‘harmonious world’ is clearly reminiscent of the Western-born (Realist) concept of ‘power-balanced politics’, which presupposes that a nation’s ability to contribute towards solving the issues of global significance is reflective of its economic and military capacities (Yiwei 2010).

At the same time, however, the outlined insights into the subject matter cannot be considered thoroughly enlightening, in the discursive sense of this word. After all, there is a good reason to believe that while elaborating on the phenomenon of ‘global governance’, in general, and on China’s approach towards becoming affiliated with it, in particular, most authors remain well within the ideological boundaries of Eurocentrism, as the analytically based approach to defining the nature of fluctuating dynamics in the domain of IR.

Therefore, there is nothing too odd about the fact that there is a well-defined weakness to the provided accounts of the ‘cause-effect’ interrelationship between the geopolitical rise of China, on one hand, and the mentioned process of the ‘global governance’ paradigm continuing to drift further away from what used to be its initial connotations, on the other. This weakness is concerned with the authors’ tendency to assume (at least formally) that China’s stance on the mentioned type of governance is rather culturally than dialectically/historically predetermined. Consequently, this appears to have prevented many of them from being able to refer to the Chinese vision of ‘global governance’, as such that provides us with the clue as to what is going to be the nature of ‘things to come’ in the arena of international politics in the near future.

In our study, we will aim to tackle the problem within the methodological framework of the Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), concerned with identifying the “the interrelation of language and social reality and how the one influences the other” (Schrieier 2012, p. 48). The rationale for choosing in favor of this specific research-tool has to do with the fact that, as practice shows, just about any analytical article, concerned with exploring a particular IR-related issue, contains a number of the implicitly defined themes and motifs of discursive importance – even in cases when the affiliated authors do not possess any conscious awareness of it.

Hence, the methodological approach to conducting the study’s empirical phases – the identification and codification of such themes and motifs (‘clusters of meaning’) and the sub-sequential subjection of the codified data to the discursive analysis. During the process, we expect to be able to find evidence in support of the study’s main hypothesis – China’s stance on ‘global governance’ signifies that the world has entered the era of geopolitical ‘multipolarity’, which in turn should result in undermining the concept’s overall methodological soundness, and legitimizing once again much-criticized Realist theory of IR.

The research’s time-range extends from the year 1995 (which marked the Chinese government’s decision to enter the world of ‘global governance’) up until today. The rationale for this is quite apparent – even though prior to the specified year China has already been playing an important part in the global body politics, the Chinese Communist government nevertheless remained highly skeptical of the idea that the country’s developmental priorities do resonate with those of the rest of world countries.

Another consideration, in this respect, echoed the fact that it was namely through the specified time-stretch that the uniquely Chinese conceptualization of ‘global governance’ (‘harmonious world’) came into being. The timetable of the study’s empirical phases (around one month) reflects our initial assessment of the research task’s complexity, as well as our experiential awareness of how long does it take to identify/codify the ‘clusters of meaning’ in the would-be analyzed articles with the help of the open code software.

Review of literature

China’s official position on ‘global governance’

Among the main approaches to ensuring the methodological soundness of the would-be undertaken CDA-inquiry, has been commonly considered the establishment of a proper discursive analysis-framework. The reason for this is that, within the context of conducting CDA, it represents the matter of crucial importance to make sure that the abstract terms, notions, and concepts, to which we will refer in the study’s sub-sequential phases, convey the same semiotics throughout the research’s entirety.

Because China’s involvement in ‘global governance’ accounts for a well-established (objective) fact, it will be thoroughly logical to go about constructing the study’s discursive framework by identifying the most notable aspects of how the concerned practice (and China’s role in it) are viewed by the country’s governmental officials and by the Chinese state-owned news agencies. Another justification for the chosen approach has to do with one of the foremost principles of tackling a phenomenological issue – a researcher must get as close to the phenomenon’s origins, as possible. Given the fact that, as it will be shown later, China’s decision to become the agent of ‘global governance’ was rationally driven, it is indeed important to identify the actual connotations of the officially provided rational explanations, in this respect.

Based on information available for access in the web-based open sources, we can outline many qualitative characteristics of how the Chinese leaders and the country’s news agencies elaborate on the subject of ‘global governance’, in conjunction with the process of China becoming increasingly affiliated with the concept in question.

Probably the main of them is that, as it appears from the Chinese officials’ speeches/interviews, they view the task of helping their country to become the legitimate agent of ‘global governance’ as such that is being closely interconnected with the innate logic of China’s socio-economic development. For example, the so-called ‘five development philosophies “innovation, coordination, green, open and sharing”, which now define China’s attitudes towards the discussed practice, have been incorporated into the philosophy of the country’s 5-year development plans as early, as during the nineties (Xi provides Chinese way 2016).

This, in turn, can be interpreted as the indication that the Chinese leadership’s decision to allow China to take part in managing world affairs has been evolutionary. That is, after having dropped some of the most inflexible postulates of the Socialist ideology, which still enjoys the officially-endorsed status in China, the CPC’s top-functionaries came to realize that their country is practically interested in becoming more open to the world, as well as assuming the responsibilities of one of the world major ‘governors’. In his 2015 interview, Chinese President Xi Jinping pointed out, “China pursues an independent foreign policy of peace and is committed to world peace and common development. In today’s world, it is impossible for China to develop on its own; only when the world thrives can China prosper” (Full Transcript para. 10).

Thus, it is specifically the consideration of ensuring China’s long-term economic and geopolitical well-being that can be assumed to have played a major role in promoting the country’s government to make an entrance into the domain of ‘global governance’.

Another noteworthy aspect of China’s take on ‘global governance’ is concerned with the fact that, as opposed to what is the case with their Western counterparts, the Chinese official figures tend to refer to this concept as such that implies the synergetic/systemic essence of the process of governing. President Xi Jinping exemplifies the validity of this statement perfectly well. After all, he never ceases stressing out the importance of taking into account the process’s sheer systemness, “Xi Jinping demonstrates that the virtues of Chinese systematic thinking for modern society are not simply a matter of well-chosen quotations from revered sources…. More fundamental is an underlying drive for systematic interconnectedness that characterizes both ancient and modern Chinese thought” (Albrowe 2015, para. 12).

In its turn, the notion of systemic interconnectedness presupposes that when it comes to solving a particularly complex global issue, the agents of ‘global governance’ must be thoroughly aware that their active involvement, in this respect, may bring about a number of non-linear/counterintuitive and consequently unforeseen effects. Partially, this explains why in their public speeches and interviews, the Chinese top-officials insist that China’s innovative outlook on what ‘global governance’ should be about is by no means intended to destabilize the geopolitical balances on the planet. According to Xi Jinping, “It is necessary to adjust and reform the global governance system and mechanism. Such reform is not about dismantling the existing system and creating a new one to replace it.

Rather, it aims to improve the global governance system in an innovative way” (Full Transcript para. 4). It can be suggested that China’s stance, in this regard, is consistent with the Confucian idea that the synergetic balance of potentials (order) is easily disruptable, which is why the agents of ‘global governance’ must think twice before applying an active effort in trying to make the world a better place. Therefore, it is thoroughly explainable why the country’s official representatives continue to stress out that by becoming the active practitioner of ‘global governance’, China is the least interested in undermining the integrity of this practice’s already established conventions.

According to Fu Ying (Head of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the National People’s Congress of China), “China is not challenging the existing international order, and China sees itself as part of the UN-based system, including the international institutions and norms” (Wei & Bo 2016, para. 4). At the same time, however, the Chinese never skip a chance to express their belief that the philosophy of ‘global governance’ must be fully consistent with the Westphalian provisions of international politics, concerned with the principle of non-interference. As Xi Jinping pointed out during his speech at UNGA 70th session, “The principle of sovereignty not only means that the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries are inviolable and their internal affairs are not subjected to interference.

It also means that all countries’ right to independently choose social systems and development paths should be upheld” (The full text 2015, para. 10). Such a vision of ‘global governance’, on the part of the Chinese governmental figures, does contradict the Western one, the proponents of which tend to regard the discussed concept as such that is meant to justify the neo-colonial aspirations of the West. In this respect, we can mention the recently emerged Responsibility to Protect (R2P) paradigm in IR, which validates the acts of armed aggression by the West against ‘developing’ countries, as an integral part of ‘global governance’, intended to serve the cause of ‘humanitarian relief’, “R2P redefines sovereignty as responsibility…

If the state is unwilling or unable to honor the responsibility or itself perpetrates atrocities against its people, then the responsibility to protect the victims of atrocity crimes shifts upward to the international community of states” (Weiss & Thakur 2010, p. 312). Consequently, this removes any reasonable doubt that China will only be willing to take an active part in solving the issues of global importance, for as long as it does not impede the country’s ability to exercise national sovereignty.

Moreover, China’s stance on ‘global governance’ implies that the Chinese leaders are no longer content with the idea that it is solely up to the West to set the ‘rules of the game’, within the context of how the concerned concept actualizes itself in practice. The clearest indication that this indeed happens to be the case can serve these individuals’ outspoken criticism of the assumption that, for as long as the discussed type of governance is concerned, the notions of ‘banking’ and ‘governing’ should be seen synonymous, “Global governance (should not) be seen as a matter primarily for the international financial institutions.

In the global age the issues that challenge our existence on this planet call for far more than general agreements on trade” (Albrowe 2015, para. 16). This, of course, implicitly calls for the loosening of the Western grip on the world economy. After all, up until comparatively recent times, the term ‘international financial institution’ was used to imply that the referred organization is Western-based, by definition.

Moreover, it also presupposes the necessity for the very paradigm of ‘global governance’ to cease being perceived as merely the mean of addressing ecological issues and enabling more and more people across the world to enjoy the pleasures of democratic living. Apparently, the Chinese regard this type of governance as such that is being potentially capable of keeping humanity on the path of evolutionary betterment.

This, in turn, presupposes heavy investments in the world’s infrastructural domain – despite the fact that from the neo-Liberal standpoint this type of investment will appear ‘unfeasible’. Hence, probably the most notable aspect of how China takes part in ‘global governance’ – the country’s government remains committed to the policy of helping the Third World nations to become economically self-sustainable, regardless of whether they happened to be ‘democracies’ or ‘dictatorships’ (Xi stresses urgency 2015).

The Chinese government’s ‘Belt and Road’ project, concerned with establishing the land-based and maritime trade routes between China and Europe/Africa, illustrates the full soundness of this statement. The reason for this is that the project’s completion can only be possible if the en-route countries enjoy economic prosperity and political stability on a continuous basis – the main focus of China’s indulgence in ‘global governance’ (China Focus 2016).

Western outlook on the significance of ‘global governance’ and China’s role in it.

In this part of the study, we focus on providing the general overview of the main ideas contained in the articles that will be subjected to the Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) through the study’s sub-sequential phases. The rationale behind this particular inquisitive move, on our part, is concerned with the fact that, in full accordance with the methodological provisions of the grounded theory (GT) research, we will need to identify the main theoretical premises, promoted by the would-be analyzed articles.

During the study’s analytical part, these premises will be compared with yet to be defined implicit ‘clusters of meaning’ – hence, allowing us to gain some preliminary insights into whether the currently dominant views on the significance of China’s participation in ‘global governance’ correlate with those that derive out of the domain of the authors’ unconscious. Consequently, this should enable us to elaborate on whether the currently deployed theoretical approaches towards tackling the phenomenon of ‘global governance’, in general and the role of China in the concept’s qualitative transformation, in particular, are discursively sound or not.

The articles chosen for the analysis are as follows: Wang & Rosenau (2009) “China and global governance”; Yiwei (2010) “Clash of identities: why China and the EU are inharmonious in global governance”; Hou (2013) “The BRICS and global governance reform: can the BRICS provide leadership?”; Hongsong (2014) “China’s proposing behavior in global governance: the cases of the WTO Doha round negotiation and G-20 process”; Lai-Ha, Lee & Chan (2008) “Rethinking global governance: a China model in the making?”; Shield (2013) “The middle way: China and global economic governance”; Weaver (2015) “The rise of China: continuity or change in the global governance of development?”; Weizhun (2014) “Muddle or march: China and the 21st-century Concert of Powers”; Grun (2008) “The crisis of global governance”; Dobson (2010) “History matters: China and global governance”. The main criterion for choosing the mentioned articles to be subjected to CDA was their comparative recentness, their discursive relevance, and their ideological consistency with each other (the authors tend to assess China’s stance on ‘global governance’ from the essentially Eurocentric perspective).

The following are the main theoretical premises, shared by the authors of the yet-to-be analyzed articles. These premises serve as the discursive foundation for the lines of argumentation deployed by the authors – regardless of what happened to be the nature of the affiliated argumentative claims.

- The emergence of the ‘global governance’ concept has been predetermined by the objective laws of history. As viewed by the authors, the ongoing process of Globalisation naturally results in bringing about the situation when the pressing issues of economic, environmental, and societal importance, faced by just about every country, can no longer be addressed on a regional/national level. As Hongsong (2014) noted, “By creating and acting through various international institutions, states manage global issues beyond borders collectively, thus construct and maintain global order” (p. 121). In its turn, this explains the strongly defined Constructivist sounding of the articles in question. The authors do subscribe to the idea that the consideration of being able to contribute to the overall well-being of humanity did play an important role, within the context of how the Chinese governmental officials proceed to make practical use of the concept of ‘global governance’.

- By assuming the role of the agent of ‘global governance’, China exhibits its willingness to play by the Western-set ‘rules of the game’ – at least in the formal sense of this word. This idea is explored throughout the entirety of each of the mentioned articles, including the most controversial ones (because of the contained criticisms of the Western outlook on what ‘global governance’ is all about), such as the ones by Wang and Rosenau (2009) and Grun (2008). For example, according to Wang and Rosenau (2009), “The Chinese government has actively coordinated its policies with other countries… China has come to accept the prevailing (Western) international rules and norms in various issue areas” (p. 8). As the clearest indication that this indeed happened to be the case, the authors refer to the fact that, as time goes on, China strives to strengthen its influence in a number of international organizations, such as the UN, IMF, and WTO. At the same time, however, most authors do admit that China’s agenda, in this respect, is rather utilitarian. As noted by Hou (2013), “China wishes to extract as many practical benefits as possible from their engagement with the international order while giving up as little decision-making autonomy as possible” (p. 359). In its turn, this is being explained by both: the fact that China is associated with the cultural/philosophical legacy of Confucianism, on one hand, and the fact that the history of China’s relations with the West naturally makes this country to mistrust the former, on the other.

- China’s approach to ‘global governance’ is deeply holistic, in the sense that the Chinese take into consideration the would-be ‘cause-effect’ repercussions of tackling global issues in an internationally cooperative manner. Just as it was implied in the Introduction, China refrains from referring to the task of solving the most pressing global problems (such as ‘global warming’ or ‘international terrorism’) within the methodological framework of Eurocentrism (Faustianism), based on the assumption that ‘the end justifies the means’ – the idea that is being promoted by each article. In its turn, this explains why the chosen academic materials contain either explicit or implicit references to the earlier mentioned concept of ‘harmonious world’ – the Chinese equivalent of the Western-coined term ‘global governance’ (Weaver 2015). What the authors agree upon is that the doctrine of ‘harmonious world’, as seen by the Chinese, can be linked to the legacy of Confucianism. As Lai-Ha, Lee, and Chan (2008) pointed out: “The ‘doctrine of holism’ derives from some Chinese philosophical appreciation of comprehensiveness of and balance in nature” (p. 5). It is understood, of course, that the assumption that China is committed to building a ‘harmonious world’ because of some purely ethical considerations, on its part, contributes even further towards legitimizing the Constructivist outlook on the nature of geopolitical dynamics in today’s world. Moreover, it encourages readers to believe that the specifics of China’s stance on the issues of global significance cannot be discussed outside of what accounts for the workings of one’s ‘Oriental’ mentality.

- China is still a developing country, and its geopolitical ambitions are mainly concerned with the country’s strive to expand the sphere of its regional influence. Even though most authors do point out the fact that China’s geopolitical influence continues to grow exponentially, they nevertheless continue to insist that this country’s interests are regionally restricted – not the least because China has not yet attained the status of a fully developed nation. This, in turn, presupposes that China continues to depend on other countries, within the context of how it manages its domestic politics, on one hand, and its foreign policies, on the other – the main reason why the Chinese leaders decided to adopt a favorable stance towards the concept of ‘global governance’, in the first place. As Yiwei (2010) pointed out, “The rising Chinese power is not just an independent power which China can use freely but a structural power depending on the world” (p. 104). The same idea defines the discursive sounding of other selected articles, as well. We can interpret it as the indication that while tackling the subject matter, their authors continued to assess the rise of China and its ‘global governance’-related aspirations in essentially phenomenological terms, which can be interpreted as yet another sign of the provided argumentative claims being ideologically biased to an extent.

- There is an objective need for the concept of ‘global governance’ to be readjusted to correlate with the realities of the 21st century’s living. Because the U.S. can no longer be considered the only hegemonic power in the world, the concept in question presupposes that the world’s most influential countries must be willing to subdue their selfish (national) interests so that there may be a lasting period of peace on Earth. This idea refers to the early 20th century’s notion of the ‘concert of powers’, descriptive of the situation when it was solely up to Britain, Germany, France, and Russia to preserve peace – despite the fact that these countries never ceased to remain mutually antagonistic. The state of ‘concert of powers’ also existed throughout the era of the Cold War. According to Weizhun (2014), “’Concert’ was applied to indicate security relations among Great Powers, or regarded as one type of regional multilateral security regimes with the alliance, cooperative security, and collective security” (p. 247). It is understood, of course, that the mentioned idea stands in striking opposition to the Constructivist assumption that the agents of ‘global governance’ will operate in the essentially ‘borderless’ (due to Globalisation) world.

Empirical research

Identification/Codification

The approach that we utilized to identify the ‘clusters of meaning’ in the selected articles is thoroughly consistent with the theoretical prerequisites of CDA, as such that accentuate that just about any public discourse reflects the never-ending process of the well-established discursive assumptions being challenged by the ideas that seek to attain discursive dominance. As Wodak (2006) argued, “CDA is fundamentally interested in analysing opaque as well as transparent structural relationships of dominance, discrimination, power and control when these are manifested in language” (p. 53).

The appropriateness of choosing in favor of this specific approach to analyzing the selected articles can be illustrated, with respect to the fact that the very notion of ‘governance’ presupposes its agents’ willingness to exercise a coercive authority while managing public/international affairs. This goes contrary to the main discursive implication of ‘global governance’, as such that presupposes the absence of the element of coercion, within the context of how different countries participate in it.

The above-stated implies that there is indeed a phenomenological quality to the questions of what accounts for China’s role in contributing to the methodological transformation of the concept of ‘global governance’ – something that once again justifies the deployment of CDA as the study’s analytical tool. Hence, the main subtlety of how we approached the task of identifying the semiotic ‘clusters of meaning’ in the chosen articles – our main objective, in this respect, was to pinpoint the explicitly and implicitly expressed ideas as to how China’s geopolitical power affects our understanding of the concept in question.

The validity of the selected analytical method can also be confirmed, regarding the highly systemic intricacies of the ‘global governance’–related public discourse, as such that has the notion of ‘power’ deeply embedded in its very conceptual core – despite the fact that many of the discourse’s participants often tend to downplay this fact.

Hence, yet another rationale for choosing in favor of CDA – this specific type of analysis does not only allow the identification of the emergent themes and motifs on each article’s individual level but also on a much higher ‘synthesised’ (systemic) level of all ten articles being tackled as mutually interrelated. In its turn, this made it possible for us to apply inquisitive inquiry in the selected articles, as a ‘whole’ – something that resulted in yielding many valuable insights into the subject matter in question.

The identification of the sought-for ‘clusters of meaning’ was accomplished by the mean of rereading each individual article and assigning the detected themes and motifs with specific codes, reflective of what has been determined the semiotic implications of the former. In the aftermath of the process’s completion, the assigned codes were clustered in groups and sub-groups – hence, making it possible for us to gain some spatially sound acumen into the qualitative aspects of the emerged pattern.

Because the proposed approach to gathering the data is rather time-consuming, the decision was made to take advantage of the open code software, as such that simplifies the process of the qualitative data being codified and ensures that the latter is collected in an error-proof manner. The preparatory phase involved converting the chosen articles (which initially came in the.pdf format) into text files, as the mentioned program only accepts this specific file format.

OpenCode makes it possible to import text from any.txt files so that some of its parts could be condensed (if necessary) and assigned with the specific codes of their own – each with its own semiotic connotation. The software also allows to compute the instances of each ‘cluster of meaning’ (designated by a specific code) occurring in the text and to compare their number with the number of the thematically similar ‘clusters’ in other texts. Consequently, this enables a researcher to identify the most commonly occurring themes/motifs in each individual article, and in the body of the reviewed literature, as a whole.

The theoretical premise behind the deployed data-gathering methodology is based on the assumption that while elaborating on the issue of China’s role in bringing about the qualitative makeover of ‘global governance’, the authors never ceased being affected by their own unconscious anxieties, regarding the practical implications of the process in question. In its turn, this implies that there are more semiotic connotations to the promoted ideas, on the authors’ part, than it may initially appear.

After having determined and codified the main themes and motifs (contained in the selected articles), we proceeded to categorise them as such that correlate with different theories of IR and with the synthesised essence of the authors’ own understanding of what the paradigm of ‘global governance’ will begin to stand for in the future. Consequently, this allowed us to reveal the earlier mentioned ‘clusters of meaning’ in each of the analyzed articles, as well as the associated discursive contents of these clusters.

As a result, we were able to ascertain the presence of such clusters in all ten articles and confirm the legitimacy of the suggestion that, even though most authors did diverge in their interpretations of ‘global governance’, the concerned academic commentaries can be referred to as one ‘synthesised whole’. Thus, there is indeed a good reason in assuming that the conducted analysis should be deemed enlightening, in the sense of being able to contribute towards deepening our awareness of what accounts for the relationship between the modern discourse of ‘global governance’, on one hand, and the current dynamics in the domain of IR, on the other.

Results

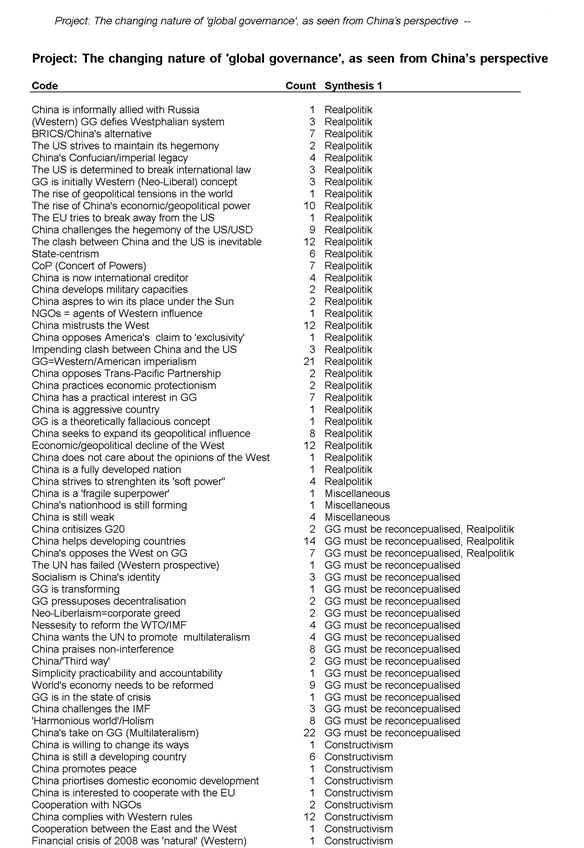

After having analyzed the chosen articles within the methodological framework of the CDA, we were able to assign the following codes to the continually recurring themes and motifs (often inconsistent with each other), articulated (either explicitly or implicitly) by the authors:

- China’s take on GG (Multilateralism), GG=Western/American imperialism, China helps developing countries, China complies with Western rules, The clash between China and the US is inevitable, China mistrusts the West, Economic/geopolitical decline of the West,

- The rise of China’s economy/geopolitical power, Worlds economy needs to be reformed, China challenges the hegemony of the US/USD, ‘Harmonious world’/Holism, China praises non-interference, China seeks to expand its geopolitical influence, CoP (Concert of Powers), China’s opposes the West on GG, BRICS/China’s alternative, China has a practical interest in GG, State-centrism, China is still a developing country, China should ‘liberalise’ its economy (Western perspective), China is now international creditor, China’s Confucian/imperia legacy, China strives to strengthen its ‘soft power, China is still weak, China wants the UN to promote multilateralism, Necessity to reform the WTO/IMF, Western criticism of China, GG is initially Western (Neo-Liberal) concept, The US is determined to break international law, Non-state actors/dialogues/cooperation (Western perspective), China challenges the IMF, Westphalian system is ‘ineffective’ (Western perspective), The impending clash between China and the US, Socialism is China’s identity, GG defies Westphalian system (Western perspective), China practices economic protectionism, Only the Western concept of GG is valid, GG presupposes decentralisation, The effects of Globalisation are objective, Cooperation with NGOs, China criticizes G20, China opposes Trans-Pacific Partnership, China aspires to win its place under the Sun, China is economically interdependent with the US, China/Third way, The US strives to maintain its hegemony, China develops military capacities, Neo-Liberalism=corporate greed, China is interested to cooperate with the EU, China is informally allied with Russia, China is willing to change its ways, The UN has failed (Western prospective), Cooperation between the East and the West, China is a ‘fragile superpower’, The US is happy with China, China opposes America’s claim to exclusivity, China promotes peace, China prioritises domestic economic development, China is aggressive country, China is a fully developed nation, Financial crisis of 2008 was ‘natural’ (Western perspective), GG is a theoretically fallacious concept, GG is in the state of crisis, GG is transforming, China’s nationhood is still forming, The EU tries to break away from the US, NGOs = agents of Western influence, Simplicity/practicability/accountability, The rise of geopolitical tensions in the world. (The abbreviation GG stands for ‘global governance’)

- Subsequently, it was determined that these codes fall into four distinctive categories (‘clusters of meaning’), broadly designated as such that belong to the discursive domains of ‘Realpolitik’ and ‘Constructivism’, on one hand, and as such that, although appearing to be ideologically unengaged, nevertheless do help us to get a better understanding of what will come of the concept of ‘global governance’ in the future, on the other. The latter two categories were designated as ‘GG must be reconceptualized’ and ‘Miscellaneous’. The first group of the codified themes/motifs adhere to the main postulate of the Realist model of IR, concerned with the assumption that the dynamics in the arena of international politics are defined by the never-ending competition between nation-states for territory and human/resources, and that war is the most natural key to solving geopolitical tensions between different countries. This specific ‘cluster of meaning’ presupposes that the concept of ‘global governance’ is nothing but yet another conversational euphemism, deployed by the West to justify its intention to keep the so-called ‘developing’ countries in the state of economic/political submission while robbing them of a chance to become fully developed. As Bew (2014) noted, “(Realpolitik) denotes an unflinching and non-ideological approach to statecraft and the primacy of the raison d’état. It involves an intuitive suspicion of grandstanding and moralizing on the international stage” (p. 49). At the opposite pole is the category of ‘Constructivism’, containing the codified references to the idea that it is not only that the discussed concept is thoroughly valid, but also that it is namely the Western (’nationless’/post-industrial) interpretation of ‘global governance’ that should be considered the only legitimate one. According to Bobulescu (2011), “In the Constructivist perspective, the change in (nation’s) interest is not only the result of constraints and opportunities in the international context but also the result of an endogenous shift in identities… States’ identities and interests are not given and fixed” (p. 53). Most commonly, these references imply that the very idea of statehood (in the classical ‘Westphalian’ sense of this word) has grown hopelessly outdated and that ‘developing’ countries (including China) will be able to benefit from cooperating with such international organizations as the UN, IMF, WTO, and with the so-called ‘Non-governmental organizations’ (NGOs).

The codified themes/motifs belonging to the ‘GG must be reconceptualized’ and ‘Miscellaneous’ categories, do not seem to be ideologically-driven (at least formally). However, most of them are used within the clearly defined Realist context, which implies that China’s influence on the changing nature of ‘global governance’ is mostly concerned with undermining the concept’s validity from within. Table 1 (see Appendices) represents the statistical pattern of the codified elements’ occurrence (in all ten articles) and shows how these elements interrelate with the designated ‘clusters of meaning’ (categories), described earlier:

As it can be seen in it, in three instances the identified semiotic references connoting ‘Realpolitik’ and ‘GG must be reconceptualised’ overlap. The following represents the typical example of such a reference: “Global governance will always be subordinate to domestic concerns, and China’s engagement with the global economic governance system will be strictly based on a realpolitik calculation of the national interest” (Shield 2013, p. 150). The table also shows that the tagged codes conveying the message ‘Realpolitik’ are the most numerous, with their number accounting for 154. These codes refer to the idea that the term ‘global governance’ is synonymous with the notion of ‘Western imperialism’, and that by claiming itself to be affiliated with it, China aims for nothing less than destroying Western hegemonic dominance in the world – pure and simple.

The reaching of such an objective the Chinese government considers the main precondition for the country to be able to remain on the path of development. The following statement typifies these references, “This (Western) model (of ‘global governance’) has led entire nations into greater poverty, debt, and bankruptcy while, at the same time, the natural resources and endowments of nations and continents are being stolen under the auspices of U.S. corporations” (Grun 2008, p. 50). The ‘Realpolitik’ suggestions, presented in each article, hint at the sheer impossibility for the concept of ‘global governance’ to prove beneficial to humanity in its present form, since there is no ‘unified humanity’ to speak of, in the first place – China’s positioning in the arena of international politics implies that the Chinese leaders understand this fact perfectly well.

The second-largest ‘cluster of meaning’ has been designated ‘GG must be reconceptualized’, with the number of the associated codes accounting for 94. As a rule, the tagged parts of the text belonging to this specific category, reveal the affiliated authors’ belief that there is something innately wrong with how ‘global governance’ extrapolates itself in practice. The codified suggestions that fall into this category also imply that there is indeed a pressing need for this concept to be transformed into something that will not only serve the interests of the West but also the interests of the ‘global periphery’.

For example, according to Lai-Ha, Lee, and Chan (2008), “China perceives global governance as an international means to building an inclusive international society in which nation-states of diverse cultures, ideologies, and politico-economic systems can coexist in peace and harmony” (p. 15), which in turn explains why, according to the same authors, “China refrains from basing its offer of aid and loans to Third World countries on the condition that liberal reforms are to be undertaken” (p. 16).

Nevertheless, the provided table also shows that there is much discursive similarity between the codified elements belonging to both of the above-mentioned ‘clusters of meaning’. This can be interpreted as the indication that there is indeed a good reason to think that China’s contribution towards inducing the qualitative transformation of the concept of ‘global governance’ is mainly concerned with exposing the erroneousness of the Constructivist assumptions, as to what this type of governance stands for.

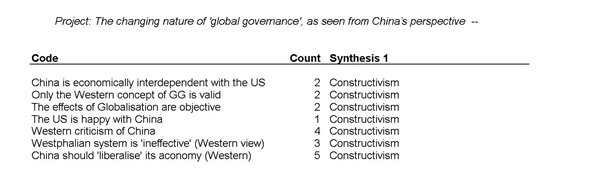

Nevertheless, while analyzing the chosen articles, we were also able to detect and codify the themes and motifs that do correlate with the Constructivist theory of IR. The most emblematic of them have to do with some authors’ promotion of the idea that China does comply with the Western-based rules and regulations of ‘global governance’. In its turn, this implies that, in full accordance with the theory’s provisions, China is in the process of adopting a new (highly Westernised) national identity – something that prompts the Chinese government to be willing to cooperate with the West and to implement free-market reforms, recommended by the WTO.

For example, according to Dobson (2010), “The 15-year negotiation to join the World Trade Organisation was instrumental in China‘s acceptance of the global rules of the road and a major driver of domestic policy reforms to change the planned economy, its institutions and its managers into more market-oriented ones” (p. 3). At the same time, however, the number of the identified ‘Constructivist’ references throughout the entirety of all ten articles does not appear to be particularly substantial – 45.

We were also able to codify what has been deemed the ‘Miscellaneous’ semiotic references of relevance (6), which nevertheless seem to correlate with the ‘Constructivist’ ones in one way or another. Most of them are concerned with encouraging readers to think that China is far from being considered fully developed, in the economic and cultural senses of this word.

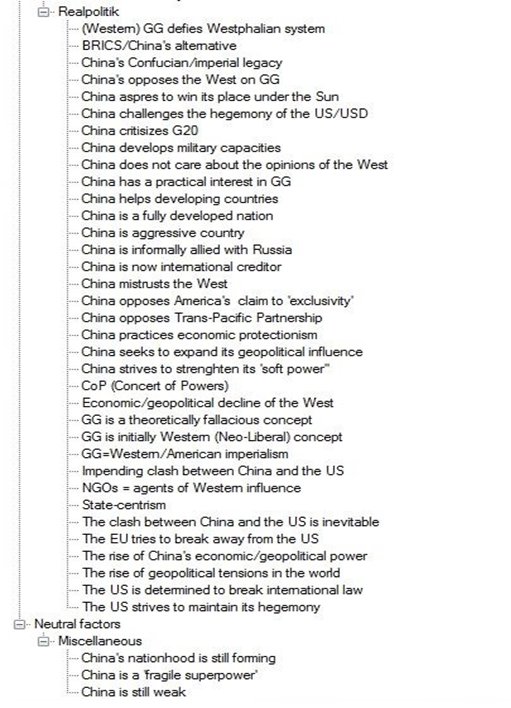

The OpenCode software made it possible for us to construct the so-called ‘synthesis tree’ as seen in Table 2 (Appendices), which shows the earlier identified ‘clusters of meaning’, in relation to their varying ability to contribute towards triggering the qualitative transformation of ‘global governance’, on one hand, and towards impeding the process, on the other.

Discussion

The obtained findings point out the fact that there is indeed a certain inconsistency between what has been determined the theoretical premises of the selected articles and the discursive significance of the majority of the tagged semiotic references. After all, whereas just about every one of these premises appears to correlate with the spirit of Constructivism in IR, the same cannot be said about most of the codified ‘clusters of meaning’.

The reason for this is apparent – as it was established earlier, the bulk of the latter is endowed with the clearly defined Realist sounding. We can speculate that the mentioned inconsistency has to do with the fact that, while elaborating on ‘global governance’, in general, and on the varying aspects of China’s participation in it, in particular, the authors strived to remain observant of the provisions of the currently dominant socio-political discourse in the West. In its turn, this discourse draws rather heavily from the ideology of neo-Liberalism, on one hand, and the Constructivist theory of IR, on the other.

The earlier mentioned Constructivist and simultaneously Western-centric concept of R2P (Responsibility to Protect), as such that supposedly defines the philosophy of ‘global governance’ in the 21st century, can be seen as the intellectual by-product of both.

Therefore, it does not come as a particular surprise that most of the analyzed articles (with the possible exemption of the one by Dobson) do subscribe to the idea that, despite its apparent deficiencies, the concept of ‘global governance’ (in its present form) is thoroughly valid. The discursive analysis of the selected articles, however, points out to the opposite, as the overwhelming majority of the codified themes and motifs reveal the authors’ subliminal anxieties/suspicions about the probability for China’s formal willingness to indulge in ‘global governance’ (while playing by the Western-set rules of the game) to serve the purpose of concealing this country’s ‘Realpolitik’ agenda.

One of the possible clues, as to why it appears to be the case, is contained in the earlier provided overview of how China’s governmental officials tend to elaborate on the subject of ‘global governance’, which helped to establish this study’s discursive ground. The logic behind this suggestion is that there is a strong diplomatic sounding to the manner, in which the country’s official representatives articulate their vision of China’s increased involvement in managing international affairs.

In its turn, this makes many of China’s official claims about its agenda in becoming an active player in the field of ‘global governing’ to appear as such that represent the primarily rhetorical value. For example, according to Chinese President Xi Jinping, “Major countries should follow the principles of no conflict, no confrontation, mutual respect and win-win cooperation in handling their relations. Big countries should treat small countries as equals, and take a right approach to justice and interests by putting justice before interests” (The full text 2015, para. 10). After all, it would prove rather challenging to refer to this objective as anything but utopian – at least when assessed within the Eurocentric discursive framework.

On the other hand, however, even the most politically neutral ‘global governance’-related statements, voiced by the high-ranking members of China’s political establishment, convey the message of dissent with the Constructivist outlook on the practice’s dialectical causes and aims. In fact, the Chinese officials often go as far as suggesting that the West no longer has what it takes to be considered the leading agent of ‘global governance’, “The West has lost its grip on ideas” (Albrowe 2015, para. 12).

There is even more to it. China persists with strengthening its ‘soft power’ in just about every region of the world – done mainly by the mean of investing in the infrastructural projects on a global scale. Because of this, and because of China’s promotion of state-multilateralism, as the conceptual foundation of ‘global governance’, the country’s current stance in the arena of IR objectively contributes towards weakening the West’s geopolitical dominance on this planet.

This is exactly the reason why the US government officials tend to refer to China (along with Russia) in terms of an acute geopolitical threat to America. As the US Defence Secretary Ash Carter noted, “We are in the middle of a strategic transition to respond to the security challenges that will define our future… We’re responding to Russia, one source of today’s turbulence, and China’s rise, which is driving a transition in the Asia-Pacific” (Zuesse 2015, para. 1).

Therefore, there can be very little effectiveness to the ‘global governance’-related cooperation between the US and China, in the factual (not merely declarative) sense of this word – the law of historical dialectics predetermines such a state of affairs by rendering both countries natural competitors. It can be argued that it is namely the realisation of this fact, on the authors’ part, which resulted in endowing their articles with the Realist overtones.

The above-stated once again illustrates that there is indeed a good reason to think that, even though China does subscribe to the idea that the globally scaled issues are better addressed by the international community, as a whole, the country’s government is mainly focused on exploring the practical (in relation to China) benefits of ‘global governance’.

Probably the main of them has to do with the fact that, as the country that actively participates in tackling the problems of global magnitude, China is able to act on behalf of its national interests in the way that is formally consistent with the Constructivist conventions of what this form of governing is supposed to be all about. This, in turn, provides China with the advantage of being able to exert an ever-stronger influence on the political dynamics in the world while avoiding the risk to end up in a state of open confrontation with the US – the country that continues to stick to its pledge to establish the essentially unipolar ‘world order’.

Based on the findings of the earlier conducted CDA, the study’s initially posed questions can be answered as follows:

- China contributes to the process of the notion of ‘global governance’ being gradually rid of its Western-centric discursive overtones. The most noteworthy implication of this particular development is that, as time goes on, more and more people throughout the world realize that the US that is no longer in the position to break international law in the most blatant manner – just as this country used to do through the 20th century’s nineties and the early 2000s. China establishes the alternative international institutions of ‘global monetary governance’ and forms political/economic alliances with countries that openly oppose the continuation of Pax Americana (BRICS, Shanghai Cooperation Organisation).

- The reason why the Chinese conceptualization of ‘global governance’ does diverge from the Western one rather substantially has to do with both:

- The historical legacy of this country has been mercilessly exploited by the West in the late 19th century under the excuse that this has helped the Chinese to enjoy ‘democracy’ (Opium Wars).

- The fact that being one of the world’s few truly independent countries (along with the U.S., Britain, and Russia), China is perfectly aware that the political dynamics on this planet reflect the geopolitical ‘balance of powers’ or the absence of such a balance. The reason why only the mentioned four countries can be regarded fully sovereign, is that along with possessing the world’s largest nuclear arsenals, they contribute towards defining the geopolitical realities on this planet to a significantly larger degree, as compared to what is being the case with the rest of influential players in the domain of international relations.

- The principle of multilateralism defines the methodological subtleties of China’s take on ‘global governance’ because the country’s government adheres to the Realist provisions of conducting foreign affairs. Since it is thoroughly natural for every country to be preoccupied with trying to expand the sphere of its political/economic influence, the geopolitical tensions between competing nations cannot be eliminated, by definition. However, it is possible to ensure the continuation of lasting peace through the establishment of the ‘concert of powers’ – the Chinese concept of ‘harmonious world’ is closely reminiscent of this term.

Conclusion

In light of the study’s findings, the initially proposed hypothesis appears thoroughly legitimate. Apparently, there can be only a few doubts that the continual rise of China results in prompting more and more political scientists to reassess the soundness of the concept of ‘global governance’, as seen in the West. This simply could not be otherwise, especially given the most recent geopolitical developments in the world, concerned with the outbreaks of the U.S.-sponsored/supported ‘orange’ revolutions all over the planet (resulting in the rise of ‘international terrorism’) and with Russia’s firm decision (supported by China) that the time has come to put an end to this kind of ‘governance’, on the part of America.

Therefore, it will only be logical to conclude that in the classical (Eurocentric) sense of this word, the term ‘global governance’ had lost the last remains of its former validity. After all, it now becomes increasingly clear to people in the ‘global periphery’ that the concerned term had never stood out for the actual governing per se. Rather, it was there to justify America’s intention to continue ‘producing’ green paper with the images of American Presidents on it (the world’s only reserve currency), as its main ‘export product’, and trading it in exchange for the valuable natural resources from other countries.

China’s uncompromising stance on defending the ‘Westphalian’ principles of international law helps to maintain the process’s momentum more than anything. Therefore, it will only be logical to conclude this research project by suggesting that China’s role in redefining ‘global governance’ is yet to be fully acknowledged.

Appendices

Table 2.

References

Albrowe, M 2015, The architectonic of Ideas: Xi Jinping’s the governance of China speech at the Booklaunch at the Chinese embassy. Web.

Bobulescu, R 2011, ‘Critical Realism versus Social Constructivism in International Relations’, The Journal of Philosophical Economics, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 37-64.

Dobson, W 2010, History matters: China and global governance. Web.

Forman, S & Segaar, D 2006, ‘New coalitions for global governance: the changing dynamics of multilateralism”, Global Governance, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 205-225.

Full transcript: Interview with Chinese President Xi Jinping 2015. Web.

Grun, N 2008, ‘The crisis of global governance’, Law and Society Journal at the University of California, Santa Barbara, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 45-58.

Lai-Ha, C, Lee, P & Chan, G 2008, ‘Rethinking global governance: a China model in the making?’, Contemporary Politics, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 3-19.

Ohmae, K 2005, Next global stage: Challenges and opportunities in our borderless world, Wharton School Publishing, Upper Saddle River.

Safdar, M 2011, ‘Global governance and mega diplomacy’, The Brown Journal of World Affairs, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 25-34.

Schrieier, M 2012, Qualitative content analysis in practice, Sage, London.

Shield, W 2013, ‘The Middle Way: China and Global Economic Governance’, Survival (00396338), 55, 6, pp. 147-168.

The full text of Xi Jinping’s first UN address 2015. Web.

Wang, H & Rosenau, J 2009, ‘China and global governance’, Asian Perspective, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 5-39.

Weaver, C 2015, ‘The rise of China: continuity or change in the global governance of development?’, Ethics & International Affairs, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 419-431.

Wei, B & Bo, R 2016, News analysis: why does China matter in improvement of global governance? Web.

Weiss, T & Thakur, R 2010, Global governance and the UN, Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Weiss, T 2015, ‘Change and continuity in global governance’, Ethics & International Affairs, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 397-406.

Wodak, R 2006, ‘Critical linguistics and critical discourse analysis’, in J Ostoman & J Verschueren (eds), Handbook of pragmatics, John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp. 50–70.

Xi provides Chinese way of thinking for global governance 2016. Web.

Xi stresses urgency to reform global governance 2015. Web.

Yiwei, W 2010, ‘Clash of identities: why China and the EU are inharmonious in global governance’, UNISCI Discussion Papers, vol. 2, no. 24, pp. 101-111.

Zuesse, E 2015, U.S. Secretary of Defence Ashton Carter implies Russia and China are ‘enemies’ of America. What next?. Web.