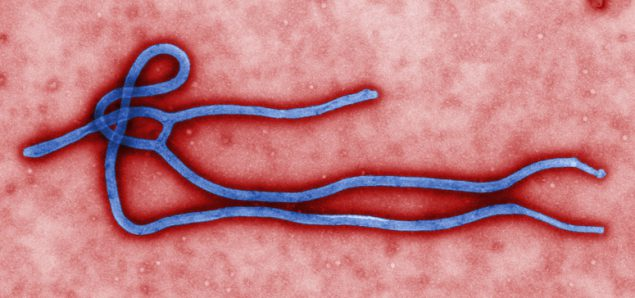

Causative Agent – Ebola virus

Fig.1 above is a microscopic representation of the Ebola virus belonging to the filioviridae family in the order of mononegaviruses (CDC,2021a). The virus is single-stranded and exhibits a distinct heterogenous threadlike structure (CDC,2021a). Upon entering the body, the virus causes cells’ death, which weakens the immune system (CDC,2021a). Subsequently, it hinders blood clotting cell formation leading to uncontrollable bleeding (CDC,2021a).

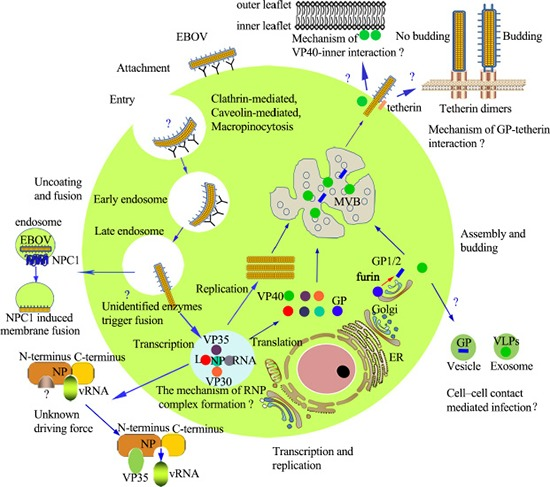

The figure above represents the virus replication stages, including attachment, whereby the cell binds the surface proteins and enters the cell (Yu et al. 2017). The next phase is the viral entry characterized by micropinocytosis, whereby the virus attaches itself to the host’s plasma membrane through invagination (Yu et al., 2017). Also, viral entry can occur through clathrin-mediated endocytosis, whereby the clathrin enables the attachment of the virus to the host cell using glycoproteins. The third step is transcription, whereby the RNA genome binds with the polymerase complex, and together they form an individual viral gene (Yu et al., 2017). The fourth phase is replication, whereby as the viral proteins increase, the positive single-stranded RNA is synthesized, resulting in rapid encapsidation. The last step is assembly and budding, in which the viral particles begin to form the nucleocapsids (Yu et al., 2017). They accumulate within the perinuclear space and are later transferred to the budding site within the plasma membrane resulting in the local concentration of the virions. The last phase is the release phase, in which the fully constituted virion is released to the host cells, and destruction begins (Yu et al., 2017).

Susceptible Population

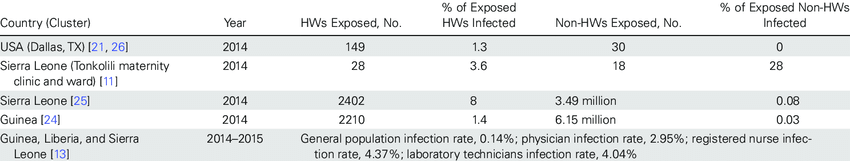

According to World Health Organization, first responders are usually pre-exposed because of the high chances of getting into contact with bodily fluids such as blood (WHO, 2021). Also, healthcare practitioners working at bio-safety organizations are vulnerable because they interact with the live Ebola virus in the laboratory, making it easier for them to be infected (Selvaraj et al., 2018). Additionally, health workers taking care of infected patients may be prone to infection because of the probability that they may be in contact with the body fluids (WHO,2021). Persons showing symptoms of Ebola should be tested immediately to curb the spread of the disease.

Healthcare frontline workers are prone to Ebola infection because of the environment in which they operate. In comparison, non-health workers are more affected by the virus, mostly contracted from patients (Selvaraj et al. 2018). In 2014, the USA had a total of 149 cases of infected health workers (Selvaraj et al., 2018). Sierra Leone had 2402 cases and Guinea 2210, representing the vulnerability of health workers working within the zoned countries (Selvaraj et al. 2018).

Symptoms, diagnosis, and vaccine side effects

The immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test determines whether a patient has antibodies related to some Ebola disease. (Niemuth et al. 2020). Symptoms of post-Ebola treatment include swelling in the area of injection, muscle pain, headache, and fever (WHO,2021). The treatment period may vary, just like the incubation period that lasts for 2-21 days (Niwmuth et al. 2020).

Prevention and treatment

Ebola can be prevented by following public health guidelines such as washing hands, avoiding contact with body fluids, and unnecessary travel (WHO,2021). The drug used to treat Ebola is Immazeb, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (CDC,2021b).

References

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a). Ebola (Ebola virus disease). Web.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). Prevention and vaccine. Web.

Niemuth, N. A., Rudge Jr, T. L., Sankovich, K. A., Anderson, M. S., Skomrock, N. D., Badorrek, C. S., & Sabourin, C. L. (2020). Method feasibility for cross-species testing, qualification, and validation of the filovirus animal nonclinical group anti-Ebola virus glycoprotein immunoglobulin G enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for non-human primate serum samples. PloS One, 15(10), e0241016. Web.

Selvaraj, S. A., Lee, K. E., Harrell, M., Ivanov, I., & Allegranzi, B. (2018). Infection rates and risk factors for infection among health workers during Ebola and Marburg virus outbreaks: a systematic review. The Journal of infectious diseases, 218(suppl_5), S679-S689. Web.

World Health Organization. (2021). Ebola virus disease. Web.

Yu, D. S., Weng, T. H., Wu, X. X., Wang, F. X., Lu, X. Y., Wu, H. B.., Wu, N. P., Li, L. J, & Yao, H. P. (2017). The lifecycle of the Ebola virus in host cells. Oncotarget, 8(33), 55750. Web.