Abstract

The two studies examined how food disgust affected the perception of a foreign culture and was associated with outgroup dehumanization. The first study focused on how groups could be dehumanized based on the level of disgust displayed by participants who were introduced to different food options of a made-up culture. The aim of the other study was to understand how modifying the cultural origins of a foreign dish and, hence, making it more culturally acceptable could impact empathy and disgust levels in participants. For both studies, participants were recruited via Harvard’s Digital Lab for the Social Sciences (DLABSS); they were offered a survey comprising Likert-scale questions. The results of the first study suggested the made-up Tilistran culture was identified as an outgroup and dehumanized on elevated levels of disgust. The second study showed that making a controversial dish a product of cultural blend does not mitigate disgust or lower the level of empathy for the animal slaughtered for preparation.

Keywords: blatant outgroup dehumanization, state disgust, intergroup disgust, empathy for the animal.

Introduction

Groups are inclined to dehumanize outgroups especially when the outgroup is distinct (Haslam & Stratemeyer, 2016). Kunst et al. (2019) show that in fact, even the slightest differences can lead to biases between groups. Food is one of the cultural dimensions that may serve as a basis for judgment for those who do not belong to the said culture (Atkins & Bowler, 2016). In a way, food is a vehicle for communicating cultural values, which, in turn, help to paint the picture of what a particular culture is like. Atkins and Bowler (2016) write that recipes often become an element of cultural exchange in which case the normalization of a previously unacceptable dish is possible. However, it does not mean that the outgroup from which the food originates will become normalized. Lalonde (2019) argues that cultural appropriation may actually harm the source culture and result in non-recognition, misrecognition, or exploitation.

The present study examines the concepts of disgust and empathy in the context of outgroup dehumanization. This state of disgust is defined as a powerful emotion that can entice people to reject whatever may seem contaminating or threatening to their civilized status (Horberg et al., 2009). Reacting to an outgroup in a repulsive manner is known as intergroup disgust (Hodson et al., 2013). Similar to state and intergroup disgust, is blatant outgroup dehumanization, a morally dangerous bias which likens those from an outside group with animalistic qualities (Buckels & Trapnell, 2013). Another construct used within the study, empathy for the animal, stems from the definition of empathy as putting oneself in another’s position to experience what they feel from their perspective (Filippi et al., 2010). The presentation of facts regarding food preparation and animal slaughtering may greatly affect levels of empathy in readers (Kunst & Hohle, 2016).

The first study hypothesizes that food disgust affects the perception of a made-up foreign culture. In turn, the hypothesis of the second study is that modifying a dish to be more culturally acceptable will result in a lower level of disgust and possibly decrease the level of empathy for the slaughtered animals. Together, the current research adds to the existing discourse by examining whether the perception of food can shape the perception of an entire culture as well as whether normalizing food through the lens of the native culture mitigates disgust.

Study 1

Participants

Participants included 733 people who were collected through Harvard’s Digital Lab for the Social Sciences (DLABSS). All participants voluntarily completed the survey online. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 99 years old (M = 33.76, SD= 18.14). There were a total of 344 men, 383 women, and 6 who answered “other”. Two attention checks were run which resulted in the removal of 85 participants, resulting in a total of 648 participants. Participants’ names were also added to a drawing for a chance to win a $50 Amazon gift card.

Procedure

Before beginning the survey, participants were told that the purpose of the study was to examine attitudes towards and reactions to various international cuisines. They were informed that the survey would take approximately 10 minutes to complete and that they would be entered into a drawing from Harvard’s DLABBS for a $50 Amazon gift card upon completion of the survey. Upon starting the survey, participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: (1) rat, (2) dog, or (3) beef. In each question, participants were shown a picture of a man eating a traditional Tilistran delicacy named Balfousum made of either rat, dog, or beef. Then, asked what their attitudes were towards that food and the individual eating it. Tilistran was created as a fake cultural group that was both regionally and nationally ambiguous.

The participants were also asked to answer an attention check question that asked the participant to please click “agree” if they are paying attention and a second one that asked what type of meat was used to make Balfousum. If a participant failed to answer these questions correctly, their data was removed from the study. Upon completion of the survey, participants were asked to answer multiple demographic questions like gender, age, income, etc. Finally, the participants were shown a debriefing form and were informed of the true purpose and hypotheses of the study.

Measures

The Empathy for the Animal Scale consisted of 5 questions and was measured using the 7-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 7= strongly agree) (Kunst & Hohle, 2016). Participants were asked to rate the 5 questions in accordance with the scale. They were asked questions such as “I feel pity for the animal that was slaughtered to produce Balfousum”. This scale showed high reliability (α = 0.95). The State Disgust Scale consisted of one question “Thinking about the dish described above, to which degree do you feel the following emotions” (Horberg et al., 2009). Participants were then asked to rate on a 7-point Likert scale similar to the previous measure on the following three emotions; grossed out, disgusted, and queasy. This scale resulted in high reliability (α = 0.93).

The Intergroup Disgust Scale consisted of 8 questions following the same 7-point Likert scale as the previous measures (Hodson et al., 2012). The survey asked questions such as “If I socialized with members of the Tilistrian cultural group, I could easily become tainted by their stigma” and participants were asked how strongly they agreed to the questions. This scale demonstrated high reliability (α = 0.81). The Blatant Outgroup Dehumanization Scale consisted of one question where participants were asked to “indicate how evolved [they] considered people from the Tilistrian cultural group to be” using a sliding scale of 5 images ranging from ape form to human (Kteily et al., 2015).

Results

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that the effect of meat type and empathy was significant, F(2, 648) = 88.73, p <.001. The participants in the dog condition had higher levels of empathy (M = 4.95, SD = 1.77) than the participants in the rat condition (M = 2.97, SD = 1.61) and the participants in the beef condition (M = 3.24, SD = 1.77). There was no significant difference between those in the rat meat and beef conditions (p =.110).

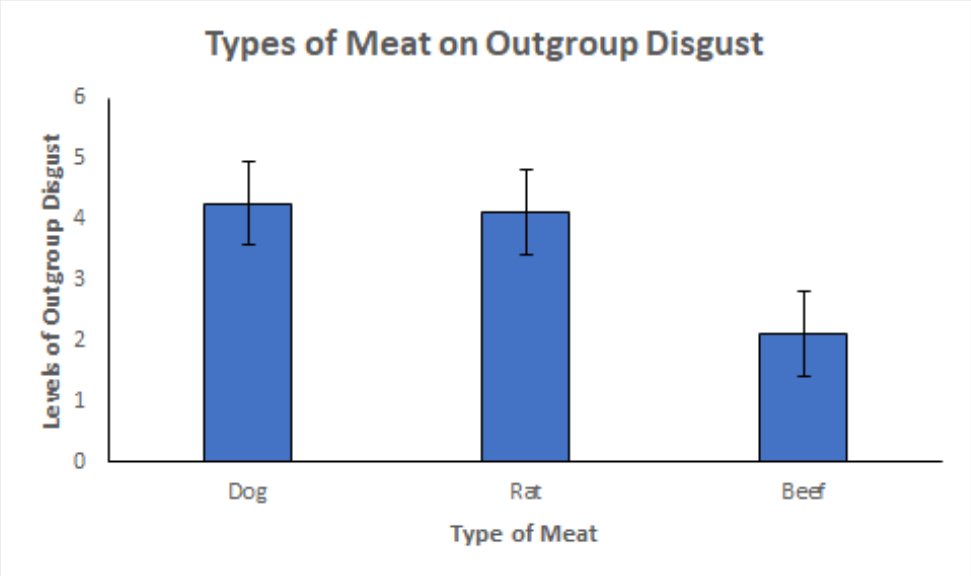

A second ANOVA showed that the effect of meat type and disgust was significant, F(2, 648) = 102.92, p <.001. Participants that were assigned in the dog condition showed more disgust (M = 4.27, SD = 1.65) than those in the beef condition (M = 2.12, SD = 1.38). The rat condition participants showed higher disgust (M = 4.13, SD = 1.77) than those in the beef condition (M = 2.12, SD = 1.38). There was no significant difference between those in the dog and rat meat conditions (p =.386).

A third ANOVA showed the effect of meat type and intergroup disgust was significant, F(2, 648) = 7.42, p =.001. The participants in the dog condition showed higher levels of intergroup disgust (M = 2.53, SD = 1.19) than those in the beef condition (M = 2.14, SD =.86). Participants in the rat condition showed higher intergroup disgust (M = 2.14, SD = 1.06) than those in the beef condition (M = 2.14, SD =.86). There was no significant difference between those in the dog and rat meat conditions (p =.153).

A fourth ANOVA showed that the effect of meat type and dehumanization was significant, F(2, 648) = 5.06, p =.007. The participants that were in the beef condition showed higher levels of dehumanization (M = 96.38, SD = 8.88) compared to those in the dog condition (M = 92.57, SD = 14.73). There was no significant difference between those in the rat meat and beef conditions (p =.073). These findings suggest that participants viewed dog and rat meat to be more disgusting to digest over beef and that people tend to also be more empathetic to eating dogs as opposed to eating rat or beef. It was also found that dehumanization was highest for those who were thought to eat beef compared to dog meat (see Figure 1).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to measure how groups may be dehumanized based on the level of disgust expressed by individuals who were presented with food options from the fabricated Tilistran culture. It was hypothesized that (1) dog and rat meat would evoke empathy towards the animal compared to beef, while rat meat will only evoke more disgust compared to beef and (2) that dog meat will evoke the most outgroup prejudice, while rat meat would evoke the second-highest, compared to beef and rat meat. The results showed that the Tilistran culture was seen as an outgroup and dehumanized based on high levels of disgust expressed by participants when presented with Tilistran delicacy. These results shed light and add knowledge about the biases that exist within individuals from different cultural groups that differ in their eating habits.

Study 2

Participants

Participants for the second study were recruited through Harvard’s Digital Lab for the Social Sciences (DLABSS). This time, it was mostly young people who decided to take part: their ages ranged from 18 to 33, with the mean age of 21.64 (SD = 4.55). All participants were of age, which they confirmed when they registered for the survey. The survey form included two attention checks that led to the removal of 85 participants; N participants proceeded further. All respondents were informed on the purpose and procedures of the study and clearly communicated that their identifying information will not be shared in any materials (Dresser, 2016). Only email addresses would be retained for a draw for a $50 Amazon gift card. The participation in the study would not result in any losses of benefits, nor will it affect respondents’ relations with California State University San Marcos.

Procedure

Before taking the survey, respondents learned that the purpose of the study was to examine individual preferences for various types of foreign foods and international cuisines. They were informed that the survey will not take any longer than 15 minutes, and to complete it, they would need to read a short description of a cultural group and their traditional dish. It was clearly stated that there are no physical risks and only small inconveniences to participating in this study, such as experiencing some discomfort when answering the survey questions. The first part contained one attention check, and those who did not pass it were disqualified from the survey.

Upon starting the survey, respondents were asked about the number of full means that they eat daily and their willingness to try the national cuisines of foreign countries (Korea, Iran, Pakistan, and others) on a scale from 0 to 6. The next part contained a description of a made-up dish with exotic, unconventional meat (cat meat). Some respondents were randomly assigned to the version of the test that stated that the dish was Chinese, while the other essentially called it a blend of two cuisines – Chinese and American.

Following the description of the recipe and its taste properties, the survey offered questions measuring respondents’ empathy for the animals killed for the preparation of the said dish on a scale from 0 to 6. Further questions examined the level of disgust and the perceived similarity or difference between the American culture and Chinese cuisine. The closing part of the survey covered the topic of influence, control, respect, and admiration with regard to American and Chinese cultures. Upon completion, demographic information was gathered, and the participants were informed about the true purpose and hypotheses of the study. At this stage, participants could withdraw from the study and remove all their data but were encouraged to keep it.

Measures

The survey helped two examine two key dimensions: empathy and disgust. The Empathy for the Animal Scale comprised five questions that used the seven-point Likert scale where 1 meant “strongly disagree” and 7 – “strongly agree (Kunst & Hohle, 2016).” Some examples of the questions were “I feel pity for the animal that was slaughtered to produce Nanjing cat soup” and “I feel sad when I am thinking about the animal that was slaughtered to produce Nanjing cat soup.” Cronbach’s alpha for the Empathy for the Animal Scale (0.945) suggests its high reliability.

The second dimension was examined using The State Disgust Scale, which consisted of one question “Thinking about the dish described above, to which degree do you feel the following emotions” (Horberg et al., 2009). Respondents evaluated their emotions (grossed out; disgusted; queasy) on the Likert scale from one to seven (α = 0.934). Lastly, the Symbolic Threat Scale (α = 0.84) employed the so-called ladder of influence, control, respect, and admiration where participants needed to choose where they would put American and Chinese culture.

Results

The first ANOVA test showed that the type of culture (pure or blend) did not have any significance with regard to empathy in respondents (F-statistic = 0.902; p = 0.347). The alternative hypothesis had to be rejected due to the p-value larger than the value that is acceptable at the chosen level of confidence. As per the second ANOVA test, the alternative hypothesis regarding disgust was also rejected (F-statistic =0.027; p = 0.599). Therefore, it was safe to assume that modifying the recipe would not mitigate the disgust levels in respondents. Similarly, the last ANOVA test proved the insignificance of modification with regard to the perception of the symbolic threat (F-statistic =0.027; p = 0.869). The mean score for the Empathy Scale was 26.92 (SD = 7.62). The mean for disgust is 14.21 and the standard deviation is 5.30. The mean for symbolic threat is 5.63 and the standard deviation is 2.80.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine whether modifying foods to be more culturally acceptable would influence attitudes towards outgroups in comparison to means that have not been “assimilated” to comply with cultural norms. It was hypothesized that dishes that were changed to be more culturally acceptable would evoke less disgust in participants compared to culturally unacceptable foods. Another hypothesis was that negative attitudes toward foreign foods would correlate with negative attitudes toward the outgroups from which the said foods originate. The results have demonstrated that presenting a dish with questionable/ culturally unacceptable ingredients as a blend of two cuisines – native and foreign – did not mitigate disgust in respondents. In addition, the claim that the soup recipe originates from the US as well did not lower the level of empathy; the majority of respondents still showed sadness for the animals used for preparation.

General Discussion

The present research revealed the powerful role of food perception and, namely, food disgust in shaping individuals’ attitudes toward a foreign culture. The results of the first study have proven to be consistent with those made by Horberg et al. (2009). Indeed, disgust served as a motivation from rejecting its source, which, in this case, was a foreign culture, and distancing oneself from what could be seen as unacceptable and even contaminating. The findings of Kunst et al. (2019) were also confirmed by the first study. Even though the respondents learned only one fact about Tilistran culture, and namely, a recipe with exotic meat, they were ready to use it as a basis for their judgment. The second study demonstrated that the normalization of a dish through its partial adoption by the native culture does not benefit the status of the source culture. In line with what Lalonde (2019) said, cultural appropriation did not result in lower levels of outgroup disgust because the source culture was still misrecognized or misrepresented.

These studies included the possible limitation of participants giving socially desirable answers which might have resulted in some dishonest answers from participants. Further research implies that fear may be a contributing factor to dehumanizing outgroups. An earlier study showed participants who did not identify with the outgroup had impacted negative feelings toward the outgroups (Mackie & Devos, 2000). This suggests the importance of future research on exploring behavioral intentions in relation to dehumanizing outgroups.

References

Atkins, P., & Bowler, I. (2016). Food in society: Economy, culture, geography. Routledge.

Buckels, E. E. & Trapnell, P. D. (2013). Disgust facilitates outgroup dehumanization. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16(6), 771-780.

Dresser, R. (2016). Silent partners: Human subjects and research ethics. Oxford University Press.

Filippi, M., Riccitelli, G., Falini, A., Di Salle, F., Vuilleumier, P., Comi, G., & Rocca, M. A. (2010). The brain functional networks associated to human and animal suffering differ among omnivores, vegetarians, and vegans. PLoS ONE, 5(5), 1-9.

Haslam, N., & Stratemeyer, M. (2016). Recent research on dehumanization. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, 25-29.

Hodson, G., Choma, B. L., Boisvert, J., Hafer, C. L., HacInnis, C. C., & Costello, K. (2013). The role of intergroup disgust in predicting negative outgroup evaluations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 195-205.

Horberg, E. J., Oveis, C., Keltner, D., & Cohen, A. B. (2009). Disgust and the moralization of purity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 963-976. Web.

Kunst, J. R. & Hohle, S. M. (2016). Meat eaters by dissociation: How we present, prepare and talk about meat increases willingness to eat meat by reducing empathy and disgust. Appetite, 105, 758-774.

Kteily, N., Bruneau, E., Waytz, A., & Cotterill, S. (2015). The ascent of man: Theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 901-931. Web.

Kunst, J. R., Kteily, N., & Thomsen, L. (2019). “You little creep”: Evidence of blatant dehumanization of short groups. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(2), 160–171.

Lalonde, D. (2019). Does cultural appropriation cause harm? Politics, Groups, and Identities, 1-18.

Mackie, D. M., Devos, T., & Smith, E. R. (2000). Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 602–616.