Abstract

To find out the effect of background music on short term memory, an experiment was carried out on two groups. This was to investigate the hypothesis that background music when played during cognitive processing would disrupt the participants’ level of concentration for the memory recall test compared to the control group, which by having no auditory distractions, these participants should have better scores on the memory recall test. The experiment was carried out on twenty-four females randomly selected and grouped into two: – an experimental group and a control group. The research study was between-subject design consisting of one group exposed to the independent variable and another group not exposed to the independent variable. The dependent variables consist of the number of words set recalled in sequence and the number of sets recalled in sequence music. The scale of measurement of the results obtained was a ratio scale; and the statistic to analyze the results was based on a repeated measure. Research findings did not outrightly support the study’s hypothesis.

Introduction

Evidence of interference of memory recall on information or material that is visually presented is quite vast. The effect of music on serial short term memory still transpires despite students or participants being overtly instructed to ignore the sounds. Interest is attached to the phenomenon for what it may reveal about the flow of information from the senses and the interplay of perceptual and memorial functions (Macken, Mosdell & Jones 1999).

The hypothesis of this study was to find out whether background music when played during cognitive processing would disrupt the participant’s level of concentration for the memory recall test compared to the control group, which by having no auditory distractions, these participants should have better scores on the memory recall test. The study further on the rationale on whether background music will provide a negative effect on memory recall predicted; the experimental group (exposed to background music) would have lower scores on the memory recall test in comparison to the control group (no music) (Campbell, Beaman & Berry, 2002).

Serial recall of ordered lists of words and pictures is impaired significantly when background noise is introduced. It is particularly pronounced when the sound changes rather than remaining one constant tone, called the “changing state effect.” Due to this particular auditory distraction effect, we believe that certain types of music can exhibit these same detrimental effects on serial recall. The independent variables for this experiment were the presence of music, the difficulty of words (set in easy medium and hard levels), and difficulty of number sets (divided into single digit and double digits) (Savan 1999).

Methods

Participants

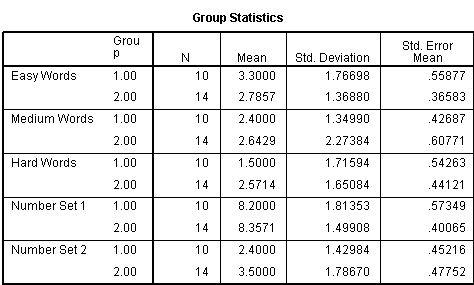

The participants of this research were a group that consisted of twenty-four females selected using a random selection method. They were all averagely 22 years old and students undertaking undergraduate studies. Neither of the participants had hearing problems nor any vision impairments despite some of them having spectacles. The participants were randomly assigned to two groups (a random number generator was used to assign participants into either control or experimental group): group 1 (without music) 10- the control group, and group 2 (with music) 14- the experimental group. Potential harm/injuries that the participants were likely or risked obtaining included embarrassment/ridicule and or stress/anxiety (Sörqvist, Marsh & Jahncke, 2010).

Procedure

A random number generator was used to assign participants into either control or experimental groups, and the experimental group was asked to leave the room. But before this was done consent forms were given out to all the participants and they were asked to fill out the necessary details. All participants were given the required and necessary instructions.

The test was carried out first on the control group which took a memory test without music. It was later asked to step out and the experimental group was then asked to take a memory test with background music. The participants were all provided with information regarding the effects of music on a serial short memory. They were asked not to look at the names of participants on the consent forms. The participants were asked to remember a sequence of randomized numbers. They had one full minute to encode the information that was supplied to them and they had two minutes to record their answers in the same sequence (Savan 1999).

The experiment was carried out between a subject design consisting of one group exposed to the independent variables and another group not exposed to the independent variables. The dependent variable is the number of words set recalled in sequence and the number of sets recalled in sequence music. It was operationally defined as the correct sequence remembered from the sets of numbers, words, and shapes shown to each participant. There were a couple of un-controlled and extraneous variables that needed to be monitored and steps are taken to reduce them. Irrelevant background sound intruding into the control group from outside the classroom was one such variable, it was necessary to try and keep the immediate area outside the classroom as quiet as possible. An individual difference in serial recall abilities is another variable that needed control by randomly assigning subjects to the two levels of the independent variable. The measurement scale was a ratio scale; and the statistic to analyze the results was a repeated measure (Campbell, Beaman & Berry, 2002).

The study did not assess any other behaviors/responses or characteristics. All participants were debriefed at the end of the test and the data collected. A slight setback was observed as two participants were disqualified both from the control group as they failed to follow the specific instructions. To reduce the risk of the potential harm mentioned above the results were kept anonymous, this was to reinsure participants that the experiment does not correlate to any known aspect related to intelligence. Also, participants received class credit for participating in the experiment (Beaman & Jones 1997).

Dissemination of the results was done through a PowerPoint presentation that documented the findings of the research collected from the study in hopes to find a connection between music and memory. Also, there was a verbal presentation of the results to the participants as a whole; combining both the control group and the experimental group, informing them if the information gathered helped support the research’s hypothesis that changes in the tone of music would negatively affect their memory or show no positive correlation between changes in musical tones and memory (Beaman & Jones 1997).

Results

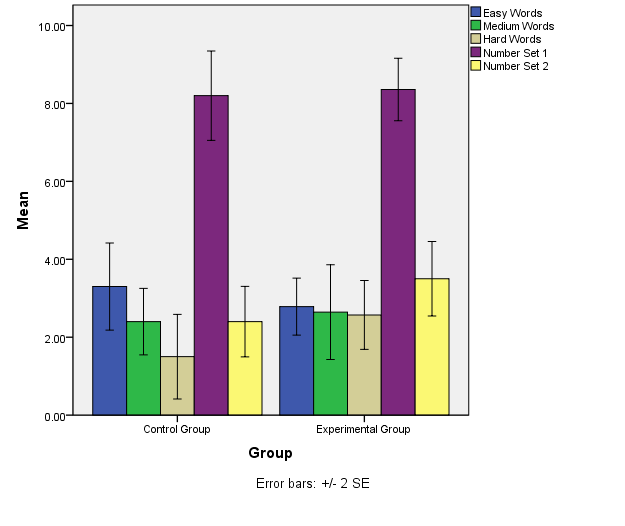

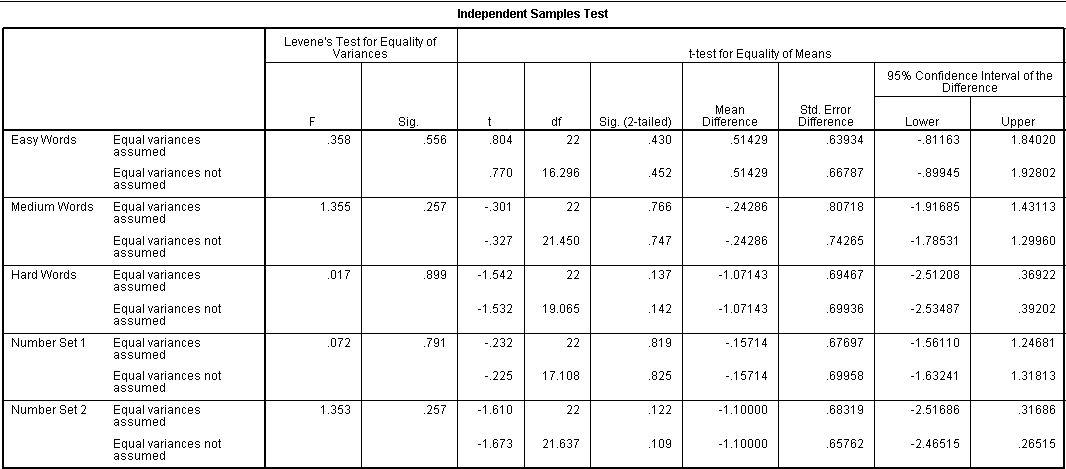

The research found out that from the results, there was no significant difference in scores between the two groups, a critical t value of 1.717 was needed to reject the null hypothesis.

- Easy Words: Control (M=3.3, SD=1.8), Experimental (M=2.8, SD=1.4), t(22)=.804, p=.43

- Medium Words: Control (M=2.4, SD=1.3), Experimental (M=2.6, SD=2.3), t(22)=-.301, p=.766

- Hard Words: Control (M=1.5, SD=1.7), Experimental (M=2.6, SD=1.7), t(22)=-1.542, p=.137

- Number Set 1: Control (M=8.2, SD=1.8), Experimental (M=8.4, SD=1.5), t(22)=-.232, p=.819

- Number Set 2: Control (M=2.4, SD=1.4), Experimental (M=3.5, SD=1.8), t(22)=-1.61, p=.122

Discussion

The results obtained from the experiment did not generally support the study’s hypothesis as they were based on the mean totaled from both the control group and the experimental group. The research found out that no notable or significant effect on the ability to recall with background music was observed across the experimental group. On the other hand, the alternative hypothesis showed there was a slight notice of improvement in most scores that had background music, but not enough to be significant in changing the results (Savan 1999; Macken, Mosdell & Jones 1999)).

The results demonstrated that the dependent variable is the memory of sequential numbers while listening to music with unpredictable tones vs. no music. There was a slight changing state of disruption of memory in both groups. This showed no overall modality differences between the groups. It will be operationally defined as the correct sequence remembered from the sets of numbers, words, and shapes shown to each participant. There are a couple of un-controlled and extraneous variables that we will need to watch out for and take steps to reduce. Directions to the participants might have been unclear that is why the result came out as they did (Savan 1999).

The experiment encountered some challenges which included; lack of surveying participants’ adeptness for music preferences and study habits; fatigue and minor stress was evident among some of the participants; some participants were closer/farther from the source of music and these all contributed to the outcome of the results. The research apart from giving its findings on the effect of music on serial short-term memory recommended for future studies/experiments on several considerations. First, the survey should use a larger sample size from the target population; this will reduce the size of the zero error expected, hence increase the accuracy and reliability of the results. Also, larger sample size will enhance idea generation, which is essential during the brainstorming stage. Secondly, the research should use fewer independent variables. Unlike in this study, we used too many independent variables (Music and No music, Difficulty of word sets, and Difficulty of Number sets) making it hard to see our main agenda of distraction.

This study can be generalized into an analysis of the whole population, argumentative generalizations, inductive arguments, or general formulations; however, the sample size of 24 respondents is a bit small to come up with an assertive conclusion or a theory (Sörqvist, Marsh & Jahncke, 2010).

Conclusion

From the experiment carried out on the two groups, it is not clear whether the effect of short-term recall is hindered in any way by background music. The research cannot be termed as either a success or a failure as it does not address the hypothesis and at the same time does not outrightly dispute it. Thus, from the challenges encountered, the research can be summed up as not as conclusive as expected but has paved way for better and improved further study/experiment to be carried out.

References

Beaman, C. & Jones, D. M. (1997). Role of serial order in the irrelevant speech effect: Tests of the changing-state hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 23(2), 459-471. Web.

Campbell, T., Beaman, C. & Berry, D. C. (2002). Auditory memory and the irrelevant sound effect: Further evidence for changing-state disruption. Memory, 10(3), 199-214. Web.

Macken, W. J., Mosdell, N. & Jones, D. M. (1999). Explaining the irrelevant-sound effect: Temporal distinctiveness or changing state? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 25(3), 810-814. Web.

Savan, A. (1999). The effect of background music on learning. Pscychology of Music, 27(2), 138-146.

Sörqvist, P., Marsh, J. E. & Jahncke, H. (2010). Hemispheric asymmetries in auditory distraction. Brain and Cognition, 74(2), 79-87. Web.

Appendix