The equilibrium price for Prescott single-bedroom rental units

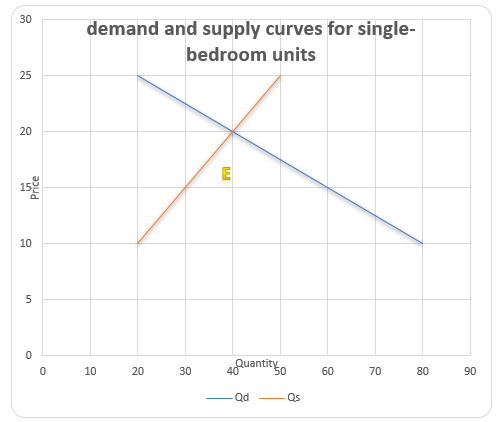

The equilibrium price is obtained at the point of intersection between the demand curve and the supply curve. First, a table is constructed from the demand and supply functions as shown in Figure 1. The second stage involves plotting a graph using the table. The stable price is 20 and the quantity of rental units demanded and supplied at equilibrium is 40. It is marked as point E on the graph in Figure 2.

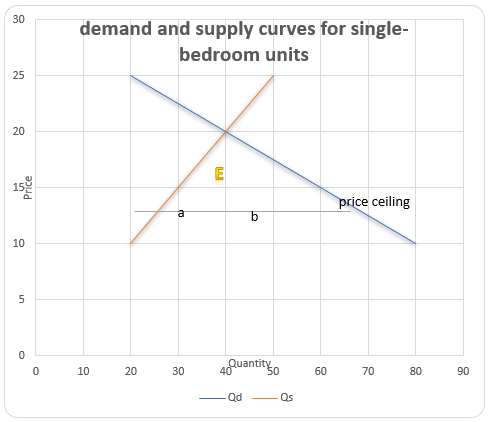

City Council in Prescott setting a price ceiling at 16

Figure 3 shows that the Council has set a price that is below the equilibrium price. It means that there will be a difference between quantity supplied and quantity demanded as shown by the gap between a and b in Figure 3. A price ceiling results in a shortage of rental units.

The price ceiling causes a state of disequilibrium. Landlords will try to find ways to reduce their costs without increasing the price. In equilibrium, landlords seek ways of improving services offered and increasing the quality of the rental units to attract customers. When there is a shortage caused by a price ceiling, landlords have no incentive to improve the quality of rental units and services offered.

In the short run, the supply of units is considered fixed and landlords are unable to reduce the supply of units. A rent ceiling makes rental units to become affordable to more people, creating increased demand and a shortage. Jenkins (2009) discusses that a rental price ceiling reduces the chance of people moving from one residential area to another. Tenants are stuck in one residential area for a long period of time because the rent is lower than the free market rent. It may result in some people, who are required to benefit from the program, missing rental units that were meant for them. Others may overstay in areas that they no longer qualify to be tenants.

Consumers of rental housing are worse off with the price ceiling because the quality of rental units will decline. A price ceiling may result in self-maintenance of rental units for tenants. The landlords may seek to reduce their cost by passing some of the cost to tenants, such as painting walls and cleaning the compound. Jenkins (2009) explains that the tenants may be unwilling to spend in some forms of maintenance because they will be unable to see the benefits of maintenance to the end of it. It results in some forms of maintenance failing to take place, which may result in tenants losing on quality of rental units. Landlords may be encouraged to let the value of their rental units to fall to match the fall in rental prices (Jenkins, 2009).

A price ceiling can result in landlords selecting tenants based on certain characteristics, such as type of job, rather than the ability to pay rent (Jenkins, 2009). In some cases, it leads to tenants offering bribes to have units reserved for them.

It can be concluded that the tenants in Prescott are not well-served by the price ceiling based on the points above. A black market and a gray market will emerge in trying to reduce the benefits that have been enforced by the price ceiling.

The Prescott City Council sets a price ceiling on apartments and leaves out rental houses uncontrolled. Tenants, who can afford rental houses, will move from apartments to rental houses. Some tenants may end up spending more than they had intended, in order to avoid the struggle to find space in rental apartments. Others may stay longer in rental apartments because they are afraid of finding a new residential area when their income level rises.

Owners of rental houses in Manhattan would prefer that there is no price ceiling because they are likely to lose tenants in the short run. In the short run, tenants who were in rental houses may choose to enter into new apartments because the rent is below the market price, even though they can afford rental houses (Childs & Palmer, 2014). It may result in more rental houses becoming vacant because of a decline in demand. In the long run, the supply side will adjust to create a new equilibrium.

Increasing the price floor for the U.S. wage rate

Recent discussion has been to increase the minimum wage to $10.10 between 2015 and 2016 or increase it to $9.00 between 2014 and 2015 (CBO, 2014). It was expected that 500,000 jobs would be lost in the process and 16.5 million workers will benefit from having their income increased (CBO, 2014).

A higher minimum wage reduces the demand for labor. Employers will want to substitute labor with other inputs, such as automated machines. The effect of raising the price floor on unemployment is lower when the economy is operating under a healthy condition. Greer, Castrejon, & Lee (2014) discuss that the unemployment level is likely to increase as a result of increasing the minimum wage. The effect of increasing the minimum wage is higher during recessions. In a healthy economy, raising the price floor for wages does not have a statistical significant effect on unemployment (Greer et al., 2014).

One of the reasons is that firms may restructure to cut costs during a recession. They may reduce the number of employees in response to higher minimum wages. Employers may also respond by cutting benefits similar to landlords when they reduce free services. Some of the benefits may be protected by law. It may lead employers to raise the qualification for employment because there is a surplus in the labor market. Greer et al. (2014) suggests that educational attainment has a stronger effect on employment than minimum wage.

In a similar manner to the discrimination in the housing problem, employers may leave out people with lower academic qualifications. They may find ways to regain higher profitability without lowering the minimum wage, such as cutting expenditure on insurance policy and free meals (CBO, 2014). They may put intense pressure on employees to increase productivity.

CBO (2014) explain that raising the minimum wage puts pressure on other income groups that are closer to the proposed minimum wage to be revised upwards. It raises the real wages of families. Employers are likely to respond with an increase in prices, reducing the purchasing power of the nominal income.

Leef (2010) discusses that one of the reasons for the wages price floor is to protect employees and ensure that firms compete on other factors of efficiency rather than lowering workers’ wages. Dufwenberg, Gneezy, Goeree, & Nagel (2007) explain that price floors do not prevent firms from increasing their efficiency and lowering costs. Their findings indicate that firms have been able to lower their costs, despite having a higher price floor.

References

CBO. (2014). The effects of a minimum-wage increase on employment and family income. Web.

Childs, J., & Palmer, J. (2014). Misallocaation costs under rent controls: Experimental evidence. SOP Transactions on Economic Research, 1(2), 49-53. Web.

Dufwenberg, M., Gneezy, U., Goeree, J., & Nagel, R. (2007). Price floors and competition. Economic Theory, 33(6) 211-224. Web.

Greer, S., Castrejon, I., & Lee., S. (2014). The effect of minimum wage and unemployment across varying economic climates. Web.

Jenkins, B. (2009). Rent control: Do economists agree? Econ Journal Watch, 6(1), 73- 112. Web.

Leef, G. (2010). Prevailing wage laws: Public interest or special interest legislation. Cato Journal, 30(1), 137-154. Web.