The impact of the culture

For ICCTC, an international consulting company, it is important to recognize that international and national culture requires careful considerations and deep knowledge of values and traditions of people. The countries selected for expansion are Iran and Malaysia (Keegan and Green 1996). One widespread understanding, though, seems to be that it is related to cultural values one way or the other and, like culture, interest in human values dates back many years.

The business culture(s) etiquette/protocol

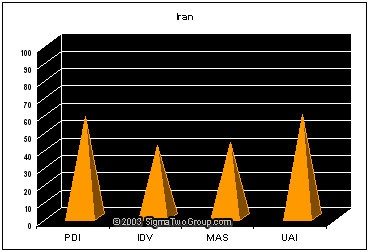

Iranian workers have little skill of working in formal organizations which, joint a high-contextual cultures. This situation means that much of what goes on as preparation, supervising and calculating is more symbolic than substantive, as will be seen.

Many Iranian institutions and business institutions are not very efficient, which is one reason why Iranian executives prefer to use personal (family and friendship) relations instead of formal communication and apply a very modified and informal management style. Iranian management style supports more detail in planning (Hofstede, 1984), and that Iranian managers thoroughly tend to take more variables into account when making strategic management decisions or in purchasing decisions than European managers, but this is for symbolic not substantive reasons (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1999).

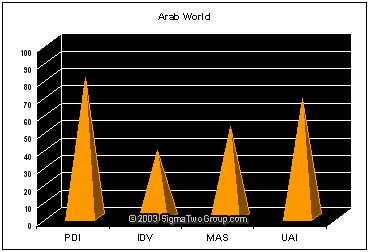

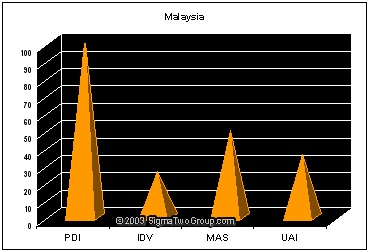

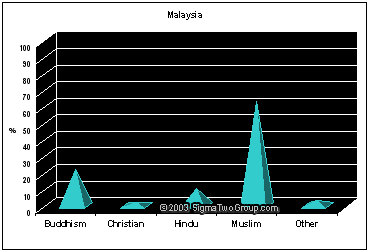

Malaysia is a South Asian country bordered Thailand, Laos and Cambodia. Characteristics of a Malaysian business organization include an autocratic, centralized style of management. Authoritarianism is a primary value in Asian cultures in general. The Malaysian management style is both a function of the family character of management and a response to the hostility so often experienced in the external environment.

The Malaysian type of culture implies (Hofstede, 1984) that Malaysian managers are seen as making decisions autocratically and paternalistically; employees fear to disagree with their boss; weaker perceived work ethic; more frequent belief that people dislike work. Hierarchy is a primary value in Eastern cultures. In the Malaysian type of culture, this means greater centralization and tall organization pyramids (Hofstede, 1984; Trompenaars, 1995).

Some say that the typified Malaysian organization structure is informal. ‘Informal’ is probably not the right word here, at least not in the sense of ‘unconventional’ and ‘unconstrained’, nor is the Malaysian organization formal in the sense of ‘planned’ and ‘impersonal’. The proper word for a Malaysian business company is rather personalized. There are conventions as well as constraints, which are not planned or impersonal, and these are given by the person in the centre of the organization (the owner or his or her representative). These conventions and constraints may change at very short notice. Another related conceptual problem is that Malaysian organizations are not personnel bureaucracies (where people, but not their procedures, are controlled), nor are they work flow bureaucracies. Personnel as well as work-flow are controlled in a typified Malaysian organization, but not as fully, consistently and impersonally (Barham and Conway, 1999).

Business Presentations: Products and Services

Iranian culture and religious traditions have a great impact on customers’ values and image of the products, brand awareness and purchasing decisions. Iranian businesses measure success by numbers and marketing limited to sales. Such Western inventions as advertising and sales promotion hardly exist at all (except in the networking sense). Concentrating so much on sales and sales numbers may occasionally mean that quality becomes of less significance. Lack of quality control is also often a problem in the workplace. Iranian companies may often appear impressive in terms of market capitalization and growth. Iranian employees value company’s image and relations with partners paying a special attention to customer satisfaction and customer loyalty (Hall, 1990).

The Malaysian workers seem to deliberately avoid entering the world of mass marketing and brand name goods. They have also no sense of after-sales service. Once a deal is done, it is done, and the nearest to anything we can call point-of-sales service would be the common Malaysian practice of ‘mooching’. Endless bargaining and a seemingly never-ending list, added to as the bargaining goes on, of ‘that little something extra’ has given the impression to outsiders that the Malaysian are among the toughest negotiators in the world. The Malaysians may appear obsessed and unreasonable, even ruthless, in negotiations. There is a Malaysian expression for this behavior when it is at its extreme, that is, to have ‘a thick face and a black heart’, to pursue one’s own ends without considering the effect of one’s actions on others, and not showing any emotion in the meantime (Brake et al, 1995).

Business Meetings and Negotiations

In Iran, all business meetings are culturally determined. During meetings, handshakes are acceptable. Iranian businessmen dress the same way as western collogues. Women should pay a special attention to their appearance and avoid short skirts or bright colors. In Iran, businessmen should be very careful about hand gestures. It is also supposed rude for businessmen to expose the soles of their feet or shoes to others (it is rude to stretch legs while sitting on the floor). The proposition to visit a home of an Iranian man should be accepted and the system of hospitality is based on sympathy. During negotiations, business decisions are slow. A western manager should not use deadlines because Iranians can cancel agreements and contracts. It is crucial to focus on financial gains and advantages of projects because it is the most important part of business for Iranians. One reason for this could be the approach taken to inheritance and succession in the Iranian business firm (Punnett, 1994).

The one thing the Malaysians are good at, though, is financial business management. Malaysian entrepreneurs “have an excellent mastery of financial levers” (Schneider and Barsoux, 2002, p. 63), and in their daily business dealing, they pay close attention to financial management. In order to always have cash available to be ready for any profitable deal that may turn up can lead a Malaysian to selling his or her goods at a lower price (even at a loss) in order to move money faster and even to borrowing money in a bank and then saving it in the same bank again to increase his or her assurance of access to ready cash, even if the bank is changing its credit policy. For Malaysians, no conflicts or misunderstanding is the main success factors (Carroll and Buchholz 2000).

During negotiations, they value patients and obedience. As long as the Malaysians make money, they feel that time is on their side. On the other hand, thinking in terms of sales and financial outcome makes the Malaysians prone to short-term thinking. However, foreign firms trying to do business with the Malaysians should not think short term. In Malaysia, much time is involved in mastering knowledge and skills and developing relations with the foreigner. The established communication with a foreign company can easily break down because of poor communication means and lack of mutual understanding. The point is not to work with the Malaysians in the sense of a complete strategic partnership, but accumulating faith, one step at a time.

Bibliography

Barham K., Conway C. 1998, Developing business and people internationally: A mentoring approach. Ashridge Research.

Bartlett, C. and Ghoshal, S. 1999, Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution. 2nd edition, London: Ramsden House.

Brake, T., Walker, D. M., and Walker, T. 1995, Doing Business Internationally.Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin Professional.

Carroll, A. and Buchholz, A. 2000, Business and Society: Ethics and Stakeholder Management 4th edn. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western Publishing Co.

Hall, E.T. 1990, Understanding Cultural Differences: Germans, French, and Americans. Intercultural Press.

Hofstede, Geert. 1984, Culture’s Consequences, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Keegan, W. J. and Green, M. S. 2000, Global Marketing 2nd edn. UpperSaddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Putti, J.M. (ed.) 1991, Management: Asian Context, Mc Graw-Hill.

Punnett, BJ. 1994, Experiencing International Business and Management 2nd edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Schneider, S.C. Barsoux. J.-L. 2002, Managing Across Cultures. Prentice Hall; 2 edition.

Trompenaars, Fons. 1995, Riding the Waves of Culture, London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.