Background

The geopolitical development of the Eurasian continent throughout history has developed according to the principle of polarity, in which ideologies, needs, and desires for territory and influence did not coincide among the most potent powers. Among these, Russia should undoubtedly be singled out as the state with the world’s largest territory, rich in natural resources, and a historical development as a powerful monarchy. On the other hand, Russia neighbors the countries of the European part of the continent, many of which — for example, Great Britain, Germany, Italy, and France — still have significant political influence today. Obviously, the geographic areas of these countries are meaningfully smaller, but in the face of concentration and the need for survival, the European powers have often joined together and catalyzed the development of military technology to intimidate Russia and demonstrate their own power. Such intimidation is part of natural political communication between countries, which is still relevant today if one follows the dialogue of major countries. Throughout history, however, Russia and Europe have not always been military rivals but instead have come together to combine efforts to fight common enemies, such as fascism. This dissertation examines the phenomenology of Russian-European relations qualitatively and in detail and demonstrates their dynamism depending on factors in the external political sphere.

Historical Background

Of primary importance is the definition of the time frame of both sides of the conflict under discussion, which will deepen the understanding of the historical value of their competition. For example, the Russian state was founded in 862 in northwest Russia today, between the key cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg, although these cities did not yet exist at that time. The foundation of the state is associated with the invitation of the Varangian brothers Rurik to the throne to rule a large country. The greater Novgorod land was a grandiose part of Russia at that time, having important economic importance as a strategic trade node of the water route from the Varangians to the Greeks (Feldbrugge 2017). Novgorod, as one of Russia’s first cities, was actively developing across the northwestern region, absorbing new territories. However, with the emergence of Moscow and the centralization of power, first in Kyiv and then in Moscow, Novgorod rapidly lost its political influence, and Russia under the leadership of the Rurik dynasty until the sixteenth century was a strong medieval Christian state built on the principle of feudalism.

On the contrary, the history of Europe goes back many more centuries if one takes into account the successive existence of the Ancient Greek and then the Ancient Roman states. In those days, there was no Russia as a formalized state yet, so there was no reason for conflict, and thus each of the European powers developed freely, with little or no serious outside pressure. The Roman Empire created Britain, which remained under the control of Julius Caesar for a long time (Redfern et al. 2018). Catalyzing state differentiation occurred due to the invasion of the fallen Roman Empire by Central Asian invaders, resulting in the Great Migration of Peoples across Europe, contributing to the formation of many current countries (Zhumagulov et al. 2018). The intensified separation of previously united peoples was realized, among others, through the arrival of Muslim culture in Western Europe, which greatly divided communities; the split of the Christian Church into Catholicism and Orthodoxy in 1054 also played a significant role in separating the European powers from Orthodox Russia (Feldbrugge 2017; Al-Bardan 2019; Kutay 2018). As a consequence, by the beginning of the new century, Europe was already a politically divided nation-state developing sovereignty.

There is no single reference point after which Europe and Russia entered the geopolitical conflict as part of international communication. While the division of Christianity was an important predictor, it was not the only one. The same can be said about the symbolic appointment of Ivan IV to the throne of Tsar of the Russian principality in 1547 (Biography 2017). Prior to Ivan IV, the leading position in Russia was given to princes or viceroys, but the political ambitions of this ruler markedly elevated Russia’s status on the European stage. In fact, there was more than a renaming of the status of the Russian monarch behind this action. This political audacity meant that Ivan IV put himself on a par with the great emperors of the ancient world, including Caesar, which could not please the European nobility. In particular, it was during Ivan IV’s reign that relations with the Livonian Confederation (modern-day Latvia and Estonia) were brought to war, which also involved Sweden, Denmark, and Lithuania (Madis 2021). Thus, the personal political needs of the Russian monarch became one of the reasons for the deterioration of relations.

The conflict between Russia and Europe has also been of a cultural nature since the countries began to move in different ideological directions. The European Age of Enlightenment, when thinkers and philosophers who qualitatively changed the moral and humanitarian values of local society began to appear in the regions of Europe, can serve as a starting point for this differentiation. Barbarism, medieval mythology, and the burning of dissenters at stake were no longer relevant among Europeans, but they were replaced by Rousseau’s humanistic thoughts, Voltaire’s oppositional sentiments, and Montesquieu’s liberal ideas (Lumen 2021). Under the Romanov dynasty in Russia, attempts to translate European culture into Russian society were made by monarchs, beginning with Peter the Great, but globally this did not lead to serious cultural success. Under Peter the Great, Russia did become noticeably stronger as a European empire and became a serious adversary to its enemies, but within the country, the cultural divide between Westerners and Slavophiles continued (Ward and Thompson 2021). The nature of the conflict between these two schools, like the nature of the conflict between Europe and Russia, came down to an attempt to define the Russian people in the history of the world.

In today’s world, tensions persist between Russia and Europe, and among the arguments in favor of their hostility are often heard military theses. In particular, it is common knowledge that the European powers (including due to the catalyzing of liberal ideas) became the birthplace of fascism. As a result of the confrontation between different ideological planes, World War I and then World War II took place. In the minds of the peoples of the post-Soviet space, these wars left a deep imprint on the internal intransigence of peoples, supported by political propaganda (Lipman 2016). However, the wars also showed another outcome: Russia was forced to unite with strong centers of European military power, and the historical alliances with Britain and France showed that relations between Russia and Europe were not built on the principle of the military conflict alone but were dynamic and adapted based on an external agenda.

In the post-war era, Russia’s key political interest was focused on the United States, with which the European country was engaged in a cold information war. Because of this, European-Russian relations cooled down noticeably, and the likelihood of a new conflict with progressive Europe decreased significantly. This is also due to the intensive globalization of the world, which is resulting in increased integration of peoples of different ethnicities. The end of the communist regime on Russian territory and the simultaneous opening of borders, including ideological borders, led to a rapprochement of countries. Today’s Russians and Europeans can visit each other’s countries and share cultural experiences relatively unhindered by visas (Tkach 2021). Although politicians continue to assert that Europe and Russia are hostile to each other, increased people with a developed critical mindset understand that this is not entirely true.

Therefore, the historical validity of the relations between Russia and the European regions makes sense since the countries were at war with each other at various points in history. The dualism of relations has persisted to this day, resulting in the ambiguity and uncertainty of this dialogue. On the one hand, the countries are collectively addressing issues of geopolitical importance and conducting joint military actions to preserve European peace. On the other hand, military tensions between the countries are increasing. It is necessary to consider the interconnectedness of both sides and to emphasize the continuity of European values in the Russian context and the Russian footprint in the European heritage.

Perception of the Other

In today’s Russia, the only politician who has the highest strategic importance for the geopolitical agenda and the building of international relations with Europe is President Putin. As for the European Union, there are many more key figures there, including French President Macron, former German Chancellor Merkel, and British Prime Minister Johnson. In addition, regional politicians from the rest of the equally respected European countries have expressed their views on Russia, which will also be taken into account in this section. In this context, it should be particularly understood that, due to the historical reasons for Putin’s long rule, European politicians have often substituted concepts, associating the whole of Russia with the person of Putin. That is why the search for relevant statements and statements should be conducted with this feature in mind.

The attitudes of individual European states toward Russia differ significantly, but the general course of this dialogue can be seen. International ties in an attempt to achieve peace between the European Union and Russia are constantly expanding to include more aspects of social, economic, and cultural life. Nevertheless, Russia, as a sizeable neighboring country to the East, remains an essential competitor for development since many economic and political decisions that carry weight for Europe are taken by Putin. It is only natural for sovereign states to never be completely united in opinion (Hicks et al. 2017). European powers, even within the European Union, have continued to clash with each other and demonstrate the cultural superiority broadcast in the minds of the local population, which means there will also continue to be some legitimate tensions between European Union countries and Russia. Public opinion polls show that only 19 percent of Europeans approve of Putin’s policies, while 27 percent favor Russia (Vice 2017). This creates a generally negative rather than positive image of Russia on the European stage, which is especially evident in the statements of local politicians looking for reasons to blame Russia. The image of the country’s economic, cultural and political rival in the eyes of the opponent is thus a natural part of the geopolitics of sovereign states.

The perception of Russia in the eyes of European politicians has never been unambiguous. An excellent demonstration of this dynamic is Angela Merkel’s 2019 tweet in which she explains that cooperation with Russia is necessary for Europe, despite all the difficulties (Figure 1). This relationship can escalate and be exposed in a particularly unflattering way when the agenda demands it. For example, Johnson’s accusatory tweet about Russia’s actions in the Salisbury poisoning (which has not been documented) illustrates the treatment of Russia as an enemy to be feared (Figure 2). Merkel also writes about the Russian authorities’ propensity to poison politically undesirable individuals, ironically pointing out that “When in Russia, it is better to avoid tea” (Merkel 2020). In this message, Merkel refers to Navalny as Putin’s main political opposition figure, poisoned by the Russian secret services, which has not been documented (Etkind 2021). The example of Navalny is not accidental, as this politician and his tragedy became the occasion for the European accusation of Russia, which European politicians have not had since the Ukrainian crisis and the case. Interestingly, Johnson previously wrote of Russia that “We may have many differences, but also much to work together…,” implying the need for cooperation to solve common European problems (Johnson 2017). An analysis of Twitter posts by the French leader showed only a respectful (rarely accusatory) attitude toward Russia and a desire for international dialogue for synergistic movement forward (Figure 3). Thus, the social perception of Russia by European politicians is dynamic and agenda-driven but always built on the principles of respect.

European powers’ attitudes toward Russia changed radically after the Ukrainian crisis in 2014 when the military presence of Russian troops on the territory of sovereign Ukraine resulted in a coup d’état, civil war, and alienation of parts of Ukrainian territories. In particular, due to the failure to follow legal procedures during the referendum, the Crimean peninsula was wholly given to the federal administration of Russia: European and Ukrainian politicians still call this procedure an annexation (Tipaldou and Casula 2019). As a result of the annexation of Crimea, Russia lost political credibility credits from European politicians, prompting the European Union to mobilize NATO military forces and impose economic sanctions against the eastern power (Horiunova 2019). The list of cooperation with NATO by European countries increased markedly after 2014, and NATO integration with Sweden and Finland intensified (Janda et al. 2017). This crisis especially clearly demonstrated Russian methods of information handling, the creation of fake news, and a “troll factory,” which aims to misinform the population and change social attitudes toward the competitor.

On Russia’s part, European powers are often perceived through the prism of the pressuring imposition of cultural values and lessons that are not inherent to Russian society. One of the most frequently mentioned recent themes in Putin’s speeches is a vector for preserving Russia’s traditional family values, including the rejection of the promotion of homosexuality and same-sex marriage (Human Right Watch 2018). Interestingly, this issue is susceptible to progressive European countries, and the attempt to destabilize Russian society has been realized through cultural interventions in Russian society through the making of documentaries about the persecution of gay people in Chechnya and active discussion of the issue (Carey 2021). For Putin, the introduction of LGBTQ+ culture into Russia is probably seen as a loss in preserving cultural sovereignty, which is why it is so important for the president to show the superiority of traditional values over the European lifestyle.

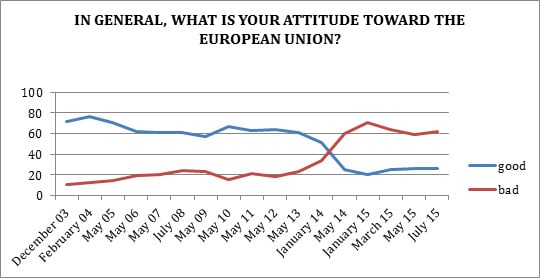

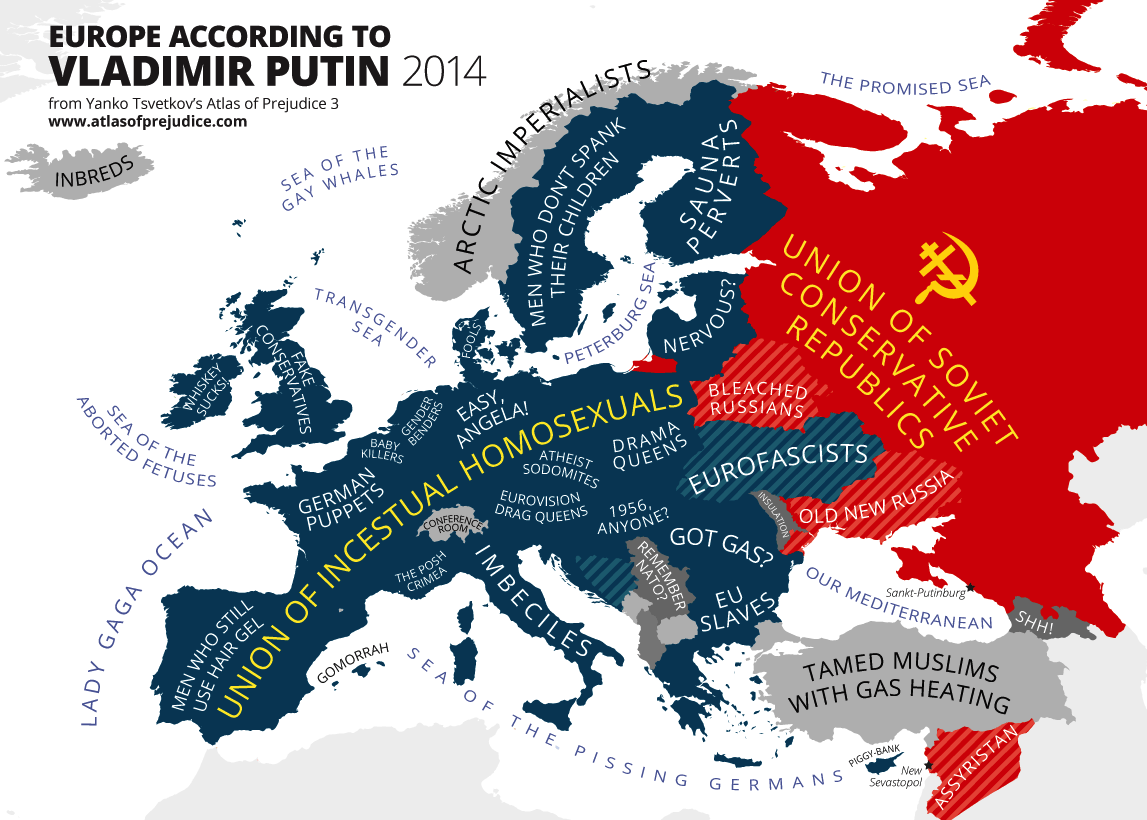

An analysis of Twitter posts by key accounts of Russian international politics shows a large number of references to the country’s history, including the wars with Germany and France. It can be assumed that these patterns are aimed at promoting Russia’s historical superiority over its European rivals, as Russia was the victor in these wars (Ward and Thompson 2021). Otherwise, a study of the publication history of official Twitter accounts yielded no results, as the main profile @KremlinRussia_E does not publish anything that allows one to judge Russia’s attitude towards European powers. However, research shows that Russian politicians’ attitudes toward Europe have changed markedly since the Ukrainian crisis as a result of developing tensions with European individuals (Daehnhardt 2018; Ikani 2019). In particular, Figure 4 shows well that Russian attitudes toward Europe have changed diametrically such that the EU is perceived by most from a negative perspective, as an enemy and an economic competitor. Understandably, such hostility may seem artificially created and reinforced for political propaganda purposes. As a result, some people may mock Russian foreign policy by creating works of art. This is the case with the Bulgarian artist Yanko Tsvetkov, who created an ironic map of Europe, indicating Putin’s supposed thoughts on what the countries of the continent are (Figure 5).

To summarize, it should be emphasized that relations between Russia and European countries are seen as highly competitive, not only economically and politically but also culturally. As a result of the military conflict in Ukraine and the sanctions that followed, diplomatic dialogue between the parties has become much more difficult. Europeans began to perceive Russia as an aggressor country, effectively manipulating information and focused on promoting its cultural vision of world development. On the other hand, for Russians, the European Union has become the birthplace of alien moral values and phenomena that are not perceived as normal by the majority of the Russian population. Through the media and statements by politicians, both sides try to portray the other in an unfavorable light while continuing to maintain and increase cooperation on key issues. As a general result, Russia and Europe cannot effectively exist without each other, but the desire to preserve and extend their ideological sovereignty leads to constant conflict and contradiction.

Persistence and Dynamics

The development of Russian-European relations may become so tense that both sides are seriously considering a military offensive to eliminate the aggressor. Undoubtedly, the military power of Russia is stronger than that of any of the European republics, but the joint action of the regions, supported by the indirect presence of the U.S. through NATO, poses a tangible threat to the Russian state. In 2021, a possible Russian military offensive against Ukraine was particularly hotly debated. European media pointed out that the main reason for such a threat was an attempt to distract the world community from mobilizing a military presence in Crimea, a Russian-controlled territory (Pengelly 2022). Regardless of the specific reason, however, the threat of a real invasion of the sovereign state of Ukraine by Russian troops has forced the European Union to discuss tactics to confront the Russian aggressor. More specifically, NATO, contrary to Russia’s requests, is expanding its borders and concentrating military power near Russia. According to diplomats involved in the talks, “diplomacy has already reached a ‘dead-end’” (Dixon and Sonne 2021, para. 1). However, such geopolitical patterns only once again confirm Russia’s importance as a strategically important player for Europe and its reluctance to engage in military conflict.

In fact, over the last decade, Russia has given many reasons for introducing a European peacekeeping mission and beginning to suppress diplomatic aggression. The Russian government has systematically ignored ECtHR judgments, restricted the central freedoms of its citizens, and violently suppressed peaceful rallies (Lukina). Any acts of dissent have become dangerous for Russian society, and the example of Navalny demonstrates this perfectly. These trends have led to intensified tensions in Europe and loud statements by European politicians. In particular, European Union President Charles Michel called Russia’s behavior “disruptive,” pointing to the provocative actions of the Russian authorities in their unwillingness to find a compromise in the dialogue with Europe (Leyts 2021). However, not a single military conflict has been realized between the parties in the last decades: it becomes evidence of tense diplomatic relations and mutual provocations, but never of crossing borders.

If one assesses Russia’s military strategies in recent years, the main areas of attack have been countries with an unstable political situation. This applies not only to Ukraine but also to the deployment of troops to Armenia and Georgia, a CSTO peacekeeping mission to manage civilian crises in Kazakhstan and Belarus (Welt and Bowen 2021). Russia did not openly introduce troops into European countries but may have acted indirectly by poisoning opposition politicians and former Russian secret service agents in other countries. These events could have been perceived as reasons to impose martial law against Russia, but European countries did not do so. From this, one can conclude that Russia is a critically important strategic foreign policy actor for Europe, and European authorities are willing to tolerate provocative behavior by their Eastern neighbor as long as it is not an emergency.

In reality, no one knows exactly what drives Putin right now, twenty years into his reign. Some journalists see the Russian president’s actions as bringing back the legacy of the Soviet Union by forming a new union state (Rosenberg 2021). Others believe that Putin has “lost his mind” amid a distortion of cognitive functions and critical thinking due to the long concentration of power (Zubov 2014). This opacity poses a particular threat to international peace, as it is not known whether a Russian politician can unilaterally initiate war. Although there is no physical war between Europe and Russia in the real world, tensions continue to build between the countries in the virtual space. In particular, this applies not only to publications on Twitter but also to tangible public propaganda broadcast through the media. It is in Russia’s interest, as well as in Europe’s interest, to create a powerful cyber information field in which the opposing side is perceived by the population as a threat. That is why Europeans have started to perceive Russia as a real aggressor with its own tactical interests in the Eastern European theater: “I do not think anyone in Europe has any illusions about how dangerous Vladimir Putin’s Russia can be” (De Waal 2021, para. 5). Accordingly, Europe has been skillfully dealing with public propaganda, making Russia look destructive to the public dialogue.

To summarize, it is true to say that Russia and Europe are in a permanent state of military conflict, and the controversial events of recent years only complicate this relationship. However, it does not seem to be in the political interest of the Russian authorities to attack Western European territory, yet Russia has been actively deploying its military presence in the surrounding areas of Ukraine, Belarus, Armenia, and Georgia. On the other hand, the European Union seems to understand its weakness against Russia clearly, so any military tactics are about finding allies and strengthening the NATO Bloc. There is no physical warfare between the conflicting sides, but information confrontations are being actively reinforced. This leads to a distortion of the real image of the opponent in the minds of the local population and entrenches public propaganda.

Termination

The confrontation between Europe and Russia is far from over and will probably never end ultimately. As shown by historical analysis, the rivalry between the parties was born long before the emergence of the current European states and is rooted in the cultural code of the inhabitants. Russia, trying to define its unique way of existence, has built its life as if in defiance of European opinion, regardless of which politician was in power. Indeed, Russian history knows of Europe-oriented monarchs who tried to transfer the lifestyle of European secular homes to Russia, but the practice has shown that these ideas did not survive in the harsh climate of Russian culture. Ironically, however, one of the most extensive periods of Russia’s existence as leader of the Soviet Union was borrowed from the ideas of European thinkers Marx and Engels, which means that Russia, without wishing to admit it, is the successor of European cultural values.

It is this pattern that leads to the idea that one day Russia will radically change its political climate and set itself up for cooperation with Europe. The focus on change on the part of Russia is conditioned by the understanding that Europe is a valuable partner for the Russian state, but that without this partnership, Russia can survive, unlike the European countries that need the resources of the largest country on the planet. The change in the political climate should be conditioned by a change in Russia’s leadership and apparatus since the current key figures are unlikely to change their attitudes on key issues of pan-European culture and values. These expectations for positive transformation reflect hopes for a mutual understanding between the countries, not only on economic issues but also on the joint regulation of aspects of social policy and the fight against threats to humanity. In the end, full cooperation between the parties, devoid of provocative and destructive diplomatic behavior, is expected to lead to incredible synergies, significantly improving the quality of life on the European continent.

Reference List

Al-Bardan, Suhaib Abdulkarim. 2019. “الإسلام في أوروبا.” AR Knowledge. Web.

Biography. 2017. “Ivan the Terrible.” Biography. Web.

Carey, Matthew. 2021. “This Is A Government-Controlled Genocide”: ‘Welcome To Chechnya’ Director David France On Russian Republic’s Anti-LGBTQ Campaign.” Deadline. Web.

Daehnhardt, Patricia. 2018. “German Foreign Policy, the Ukraine Crisis and the Euro-Atlantic Order: Assessing the Dynamics of Change.” German Politics 27 (4): 516-538.

De Waal, Thomas. 2021. “Judy Asks: Is Europe in Denial About Russia?” Carnegie Europe. Web.

Dixon, Robyn and Sonne, Paul. 2021. “Russia Says ‘No Grounds’ for Further Talks on Security amid Heightened Tensions.” The Washington Post. Web.

Etkind, Alexander. 2021. “The Art of Navalny and the History of Corruption.” Current History 120 (828): 287-289.

Feldbrugge, Ferdinand. 2017. A History of Russian Law: From Ancient Times to the Council Code (Ulozhenie) of Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich of 1649. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff.

Fisher, Max. 2014. “This Very Funny Map Shows What Vladimir Putin Really Thinks of Europe.” Vox. Web.

Johnson, Boris (@BorisJohnson). 2018. “I congratulate our security service…” Twitter, 2018. Web.

Johnson, Boris (@BorisJohnson). 2017. “Arrived in Russia…” Twitter, Web.

Hicks, William D., Carol Weissert, Jeffrey Swanson, Jessica Bulman-Pozen, Vladimir Kogan, Lori Riverstone-Newell, Jaclyn Bunch et al. 2018. “Home Rule Be Damned: Exploring Policy Conflicts between the Statehouse and City Hall.” PS: Political Science & Politics 51 (1): 26-38.

Horiunova, E. O. 2019. “Russian Militarization of Crimea as a Threat to the Security of The European Union.” Political life 1 (2019): 74-78.

Human Right Watch. 2018. “No Support.” HRW. Web.

Ikani, Nikki. 2019. “Change and Continuity in the European Neighbourhood Policy: The Ukraine Crisis as a Critical Juncture.” Geopolitics 24 (1): 20-50.

Kutay, Taceddin. 2018. “Historical Roots of ‘European Islam’.” Web.

Leyts, Barend. 2021. “Readout of the Telephone Conversation between President Charles Michel and Russian President Vladimir Putin.” European Council. Web.

Lipman, Maria. 2016. “What Russia thinks of Europe.” ECFR. Web.

Lukina, Anna. “Russia v ECtHR-Resistance or Dialogue: A Comparative Analysis.” SSRN: 1-32.

Lumen. 2021. “Enlightenment Thinkers.” Lumen Boundless World History. Web.

Macron, Emmanuel (@EmmanuelMacron). 2018. “La Russie est une grande puissance européenne.” Twitter, Web.

Madis, Maasing. 2021. “Livonia and Depiction of Russians at Imperial Diets before the Livonian War.” Studia Slavica ET Balcanica Petropolitana 1 (29): 36-62.

Merkel, Angela (@amerkel57). 2019. “While staying true to who we are…” Twitter, Web.

Merkel, Angela (@amerkel57). 2020. “When in Russia, better to avoid tea” Twitter, Web.

Janda, Jakub, Ilyas Sharibzhanov, Elena Terzi, Markéta Krejčí, and Jakub Fiser. 2017. How do European democracies react to Russian aggression? European Values 22. Web.

Pengelly, Martin. 2022. “Russia ‘Very Likely’ to Invade Ukraine Without ‘Enormous Sanctions’ – Schiff.” The Guardian. Web.

Redfern, Rebecca, Sharon DeWitte, Janet Montgomery, and Rebecca Gowland. 2018. “A Novel Investigation into Migrant and Local Health-Statuses in the Past: A Case Study from Roman Britain.” Bioarchaeology International 2 (1): 20-43.

Rosenberg, Steve. 2021. “What is Russia’s Vladimir Putin Planning?” BBC News. Web.

Tipaldou, Sofia, and Philipp Casula. 2019. “Russian Nationalism Shifting: The Role of Populism since the Annexation of Crimea.” Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-soviet Democratization 27 ( 3): 349-370.

Tkach, Olga. 2021. “Care for the Visa: Maximising Mobility from Northwest Russia to the Schengen Area.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 11 (2): 1-5.

Vice, Margaret. 2017. “Publics Worldwide Unfavorable Toward Putin, Russia.” PRC. Web.

Ward, Christopher, and John Thompson. 2021. Russia: A Historical Introduction from Kievan RUS’ to the Present. Milton Park: Routledge.

Welt, Cory, and Andrew Bowen. 2021. Azerbaijan and Armenia: The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. Library of Congress Washington DC. Web.

Zhumagulov, Kalkaman, Aigerim Akynova, Gulnar Kozgambayeva, and Aliya Ospanova. 2018. “The Time of Great Changes: The Migration Period as a Stage in the Eastern Roman Empire Origin.” Studies and Articles 2 (34): 15-24.

Zubov, Andrei. 2014. “Interview: In Crimea, Putin Has ‘Lost His Mind’.” RFERL. Web.