Abstract

This proposal presents details for a research project that will investigate the lived experiences of first-generation Latino veterans who decided to stay in the US after military service. Up to ten former military members will be recruited from locations that offer veteran services. The project will then use semi-structured interviews to collect data, which will then be analyzed for common themes. The proposed research will be directed by a theory of acculturation and a military transition model, and its rigor will be ensured by recruiting two additional investigators for triangulation. The research will have a tentative timeframe of eight months.

Introduction, Justification for Research, and Purpose of Research

Both migrants and veterans face many challenges during their transition to new lives. For migrants, the process includes becoming integrated into a new community, and for veterans, it consists of reintegrating into the civilian community (Blackburn, 2016; Kelly, 2016). For migrant veterans who decide to stay in a new country after service, the transition process is two-fold. However, no recent articles explicitly investigate this topic. The presented proposal will focus on first-generation Latino migrants who stayed in the US after military service. Its purpose will be to capture and describe their experiences with the help of phenomenology.

In Hawaii, as well as other regions of the US, the term “Latino” refers to the people “whose ethnic origins can be traced to Latin America: Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central or South America, or other Spanish, Hispanic, or Latino countries/regions” (Sánchez-Johnsen, 2011, p. 152). Furthermore, a migrant is a “person who moves from one place to another,” and the word “immigrant” refers to moving from one country to another (Oxford University Press, n.d.). The generations of migrants are used to determine the number of generations that a family has spent in a new country; first-generation migrants are the ones who had been born in one country and then immigrated (Falconier, Huerta, & Hendrickson, 2016; Sánchez-Johnsen, 2011). Finally, a veteran is a person who used to be a member of the armed forces (US Department of Veterans Affairs [DVA], 2018). To summarize, the population that is of interest for this proposal is the people born in Latin America and immigrated into the US after completing their military service in the US Army, which means that they are first-generation Latino immigrants and veterans.

It is not clear how many first-generation Latino members are engaged in the military force of the US. According to the most recent data, non-US-born service members constitute about 3% of the US armed forces, and a portion of them are Latino (“Total available active military manpower,” 2019). Also, there is some information about Hispanic veterans in the US; in 2016, there were 1,469,868 of them, and they constituted 7% of the whole veteran population (US Department of Veterans Affairs, n.d.). Combining the two numbers is difficult since the veteran information refers to all living veterans, and assuming that for the past decades, 3% of all groups of military service members were not native-born is not very realistic. Still, this information implies that the total number of all living Latino VMs might be estimated at 44,000 people.

This estimation shows that the military as a source of naturalization is not a very common vehicle for migration. However, it satisfies the need of the US military system for recruits, which is why it is socially significant (Chishti, Rose, & Yale-Loehr, 2019). More importantly, both veterans and migrants experience difficulties reintegrating into their new communities worldwide (Blackburn, 2016; Kelly, 2016). However, migrant veterans, primarily Latino migrant veterans, are not involved in research often.

The researcher is actively engaged in veteran communities and veteran services in Hawai‘i and is a Veteran himself, which calls for special attention to potential biases. The proposed research will investigate this understudied area, and the researcher will employ a sound methodology that considers the issues of positionality, ethics, and rigor. The primary stakeholders of the research are social workers since the findings will be of interest to them. Still, veterans, migrants, and the entire community of the study’s settings can potentially benefit from improved insights into the experiences of VMs.

Problem Overview

Service in the US military is voluntary, but the conditions of entering the service do not imply that anyone can randomly join. Besides fitness requirements, an opportunity to serve is provided either to US citizens or permanent residents who have already received a resident status before joining the service (Leal & Teigen, 2018). Permanent residents include immigrants to the US who are awaiting a decision on citizenship.

Military naturalization refers to obtaining citizenship after and as a result of military service. This migration pathway is not very actively used, but over the past century, 760,000 such cases have been recorded (Chishti et al., 2019). As of 2019, the active military personnel in the United States included 1,282,000 individuals (“Total available active military manpower,” 2019). Of this number, 3% (approximately 40,000) were men and women born outside of the US (“Total available active military manpower,” 2019). Of those born outside the US, a large category is represented by first-generation Latinos. These data indicate the need for a more detailed analysis of former military transition in general and Latinos in particular.

Latino migrant veterans experience two different types of transition, and each of them is connected to challenges. The core concerns of veterans who transition to civilian life include finding employment and housing, ensuring one’s health (physical and mental), and staying connected with one’s family and community (Derefinko et al., 2018; Hachey, Sudom, Sweet, MacLean, & VanTil, 2016; Pease, Billera, & Gerard, 2015; DVA, 2018). Migrant integration processes share the concerns of employment, social integration, and health. Still, for them, the issues of acquiring a new language, securing citizenship, and, possibly, being separated from their families are also important (Benton & Embiricos, 2019). Furthermore, acculturation is an additional transition process for migrants (Benton & Embiricos, 2019; Kelly, 2016; Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe [OSCE], 2018). In general, a successful transition for both groups is defined by navigating these complex journeys with maximum positive outcomes.

Military transitioning can be challenging for several reasons. First, the needs of veterans may be different from those of non-veteran people; for example, they may have retired because of health problems or experience the psychological consequences of wartime (Derefinko et al., 2018; Hachey et al., 2016; Pease et al., 2015). Second, the process of transitioning itself can be a challenge that requires a specific preparedness for some adjustments (Derefinko et al., 2018). In addition, cultural and identity changes can also occur due to military-to-civilian transition (Cathcart, 2017; Cooper, Caddick, Godier, Cooper, & Fossey, 2018). These difficulties are reflected in disturbing statistics; for example, DVA (2018) reports that over 14% of suicides in the US are committed by veterans (based on 2015 data). Thus, the challenges that are faced by veterans are an essential topic to research.

Migrants are more likely to experience problems with securing health insurance and occupation, which can affect their income and health when compared to the non-migrant population. It is noteworthy that specifically first-generation Hispanic immigrants in the US demonstrate better health than non-Hispanic American people, especially as far as mental disorders are concerned. Still, in case negative economic factors are present, that advantage can disappear (Alarcón et al., 2016). Naturally, migration is also associated with a lot of stress, which is not a positive factor for a person’s mental health (Falconier et al., 2016; Fortuna et al., 2016; Hachey et al., 2016). Acculturation processes are also health predictors; more significant conflicts between native culture and that of the country of migration are associated with more health problems (Detollenaere, Baert, & Willems, 2018). Overall, the experiences of immigrants are complex and diverse, resulting in both positive and negative factors to be taken into account.

The specifics of the setting, which is the state of Hawaii, are also noteworthy. Latino immigrants are a numerous group in the US (roughly 16% of the population). Although their percentage is slightly smaller in Hawaii (9%), it has been growing at an increased rate in the past decade (Gupta & Haglund, 2015; Sánchez-Johnsen, 2011). Gupta and Haglund (2015) and Sánchez-Johnsen (2011) report that some of the current challenges of the Latino population in Hawaii include linguistic barriers and the need for healthcare, education, and legal services. Furthermore, Hawaii is home to many veterans who constitute 11% of the state’s adults (Shaikh, Hall, McManus, & Lew, 2017). A common issue for this group is the access to healthcare because veterans may have specific health needs that can be difficult to address in Hawaii, including, for example, those related to hearing loss (Shaikh et al., 2017; Whealin et al., 2015). Thus, the experiences of Latino VMs in Hawaii are likely to be specific and worth exploring.

Finally, it should be noted that the experiences of veteran migrants incorporate those of migrants and veterans. For example, migrants are more likely to have difficulties with socialization, especially if they are separated from their families (Benton & Embiricos, 2019; Kelly, 2016). However, research demonstrates that social inclusion and support are a critical factor that facilitates the military-to-civilian transition (Hachey et al., 2016), which puts migrant veterans in a specific and challenging position. As a result, the experiences of Latino migrant veterans are likely to be shaped by multiple factors that can be both beneficial and detrimental. Given the importance of transitioning for the lives of migrant veterans, investigating the dual transitioning of first-generation Latino veterans is an important direction of research inquiry.

Knowledge Status

Within the currently available research, studies on veteran transitioning are relatively numerous (Elnitsky, Fisher, & Blevins, 2017). They focus on the investigation of veteran needs, including self-reported ones (Derefinko et al., 2018; Maharajan & Krishnaveni, 2016), as well as the process of transitioning (Albertson, 2019), including its different aspects, for instance, cultural transition or social reintegration (Cooper et al., 2018; Elnitsky et al., 2017). A sizeable recent publication is a book by Academic Press, which is dedicated to reintegration issues, including its definition, theoretical framing, and other elements (Pedlar, Thompson, & Castro, 2019; Truusa & Castro, 2019). In addition, there are studies, including quantitative ones, that look into the factors that can facilitate transition; they consider, for instance, social support and diverse psychosocial interventions (Ainspan, Penk, & Kearney, 2018; Hachey et al., 2016). However, most of the relevant research is qualitative and is introduced to investigate the phenomenon of transitioning in detail.

Researchers have explored the experiences of Indians (Maharajan & Krishnaveni, 2016), British (Cooper et al., 2018), Canadian (Cathcart, 2017), Bulgarian (Terziev, 2018), and American (Ahern et al., 2015) military members. This literature describes the process of reintegration as challenging for veterans because of multiple changes in their lives, potential health problems, and the importance of social reintegration; negotiating these challenges is typically facilitated through social support, social services, and medical and psychosocial interventions.

Similarly, the topic of migration cannot be considered understudied. Relevant studies are likely to focus on challenges, differences from the general population, and varied aspects of integration and acculturation (Detollenaere, Baert, & Willems, 2018; Painter & Qian, 2016). Researchers have explored the experiences of Latino migrants in the US (Alarcón et al., 2016; Falconier et al., 2016; Fortuna et al., 2016), including ways to measure acculturation in Latinos (Meca et al., 2017). Qualitative studies, including those by Alarcón et al. (2016), Cardoso et al. (2019), Kelly (2016), and Ni, Chui, Ji, Jordan, and Chan (2016), suggest that migrant reintegration factors include language proficiency, cultural dynamics, access to education and healthcare, and employment.

The number of studies that cover both topics is significantly smaller. Horyniak, Bojorquez, Armenta, and Davidson (2017) reported the problem of non-citizen veteran deportation and covered some of the issues that could affect migrant veterans, primarily as related to healthcare and the stress of securing citizenship. Atuel, Hollander, and Castro (2018) wrote about minority service members in the US, including Latino and Hispanic members. However, their paper focused on reasons for joining the military rather than the post-service period. Also, Leal and Teigen (2018) discussed voting practices of discharged military service members, including Latinos. Finally, Wong (2017) mentioned Latino veterans in a discussion of “ataques de nervios,” which is a factor of mental health in immigrant veterans, but it is a very narrow focus.

Gaps in Knowledge

To summarize, the amount of literature covering migrant integration or veteran reintegration is not limited, but when Latino migrant veterans are considered, almost no information can be found. Even when Latino veterans are mentioned, no premises of social adaptation are given. In addition to health issues, no social aspects are taken into consideration. As a result, it is necessary to use the information from the sources on adjacent topics to prepare a literature review for this one.

Theoretical Perspectives

No model for the phenomenon of interest (migrant veteran transitioning) exists to inform this study. However, there are models and theories that describe different aspects of military and migrant transitioning, and they are going to be used to guide this project. First, the multidimensional model of bicultural identity (MMBI) will be utilized. According to MMBI, cultural change needs to be viewed in continuity to describe the complex processes and different cultural identities that bicultural individuals adopt over their lifetime (Robbins, Chatterjee, & Canda, 2011). This framework is a helpful guideline for the migrant side of the studied question, and it can be applied to the veteran one as well since military culture is different from the civilian one (Cathcart, 2017; Cooper et al., 2018). For the proposed research, its focus on continuity and acculturation will be helpful, but acculturation is not the only process that is important for migrant veterans.

For the military aspect, a military transition model (MTM) will be used. There is no unified model (Pedlar et al., 2019), but the one described by Blackburn (2016) includes pre-release, release, and post-release factors and thus incorporates many relevant elements. Furthermore, for the purposes of determining the anticipated outcomes of transitioning, the criteria that are commonly employed by relevant organizations will be used. Specifically, the migrant integration factors by OSCE (2018) and the veteran integration factors of DVA (2018) will be considered.

It is noteworthy that OSCE (2018) is not a US organization, but for the time being, no similar assortment of migrant integration factors authored by a US body was found. Also, the tasks and challenges related to migration appear to be similar across countries, and they are reflected in the relevant literature (Alarcón et al., 2016). In addition, neither OSCE (2018) nor DVA (2018) actually presents the integration criteria as a model (or a list). However, they do discuss multiple factors, which can be extracted from their materials. As a result, it is possible to use OSCE (2018) for migrant integration criteria and DVA (2018) for those meant for veterans.

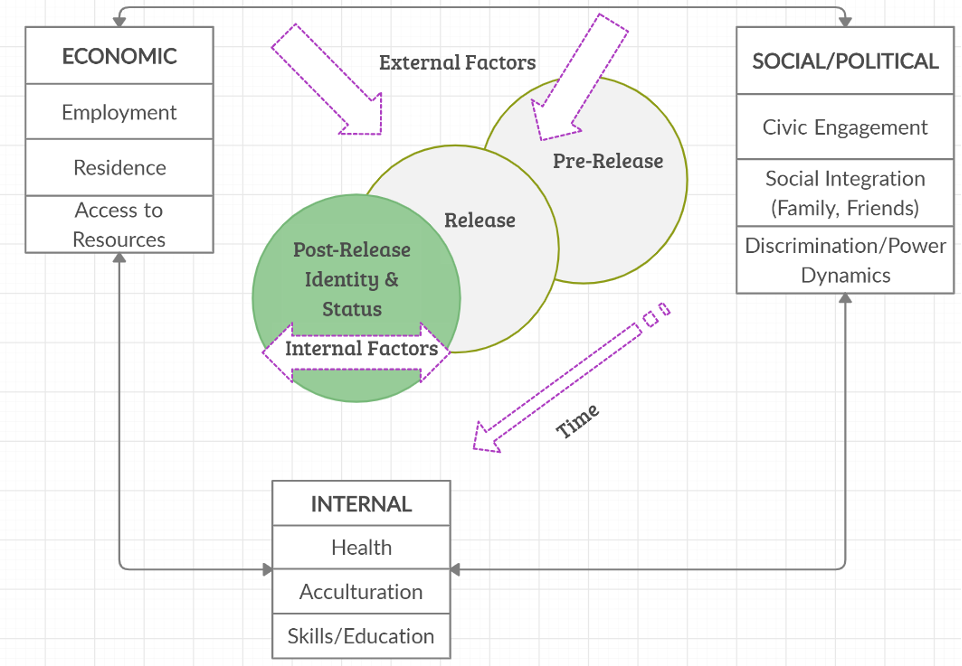

The two models (MMBI and MTM) and two integration guidelines will help to form the tool for data collection and guide data analysis. Their combination reflects the dual challenges that are faced by first-generation Latino migrant veterans, and their focus on the details of the transition experience and outcomes makes them suitable for a phenomenological, interpretivist study. A tentative merge of the four theoretical frameworks is proposed in Figure 1. As can be seen from the graphic, the final model will integrate MMBI’s attention to changes over time and cultural factors, MTM’s consideration of pre- and post-release state, and the interactions between the internal and external factors identified by OSCE (2018) and DVA (2018). All of them are likely to affect the participants’ identity and status.

Study Purpose and Questions

This research asks the following question: what is the lived experience of first-generation Latino veterans who decided to remain in the US after leaving the US military? This question is not considered by recent studies, which calls for a broad, qualitative inquiry. The proposed research will have the purpose of investigating and describing the experiences of the population of interest, and it will employ qualitative methods to achieve this goal.

Methods

Design

The presented proposal outlines a qualitative phenomenology study that will utilize individual semi-structured interviews and purposive sampling. This decision is justified by the need to respond to a research question that focuses on the lived experiences of a group and intends to produce an extensive and insightful description (Mayan, 2009). In turn, this approach implies the need for a standpoint that is not positivistic (Braun, Browne, Ka’opua, Kim, & Mokuau, 2014). As pointed out by Mayan (2009), the interpretivist paradigm pays attention to subjective perspectives and experiences, making it especially appropriate for phenomenology. A recent dissertation uses the same approach to studying veterans (Daniels, 2017), but it does not focus on Latinos, which means that a new phenomenological study is justified.

Sample

The studied group consists of the people who are Latino, first-generation migrants, and former members of the US military (veterans), which are the inclusion criteria. The sampling will be purposive (Curtis, Gesler, Smith, & Washburn, 2000; Gray, Grove, & Sutherland, 2016). I hope to recruit individuals who are considered successful and unsuccessful in their transitioning. Indeed, the idea of a successful transition and integration does appear in the literature. It often refers to positive outcomes in terms of integration, including its social, employment, and health aspects (Ahern et al., 2015; Blackburn, 2016). However, these features are difficult to assess during the research recruitment stage. Consequently, it is proposed to involve migrant veterans who report that they are either satisfied or not satisfied with their current transitioning state. Thus, the sampling strategy will be characterized by the quotas aimed at representing the two subgroups.

Another factor that is preferable to consider is the date of retiring; it would be helpful to involve people who started their transitioning earlier (for example, ten years ago) and later (for example, five years ago). Other demographic characteristics of the participants (age, gender) will be less important. The project will not exclude people with various disabilities since health problems are an important factor that affects transitioning (Hachey et al., 2016). People who are economically disadvantaged will be considered as well since this factor is another potential element of transitioning. People with limited proficiency in English will be considered if they apply, and they will be provided with translation and interpretation services. However, people who are particularly likely to be affected by coercion, especially people with impaired mental capacity, will be excluded since they are a particularly vulnerable group, as described by the University of Hawaii [UH] (2019).

As a result, the recruited sample may be quite diverse; it might include people of different ages and genders with various levels of experience in the military and with different numbers of years spent in the new country. Similarly, different military branches may be involved, although the recruitment process will not seek to diversify the participants based on these factors. Instead, the primary diversification principle will be associated with people viewing their transitioning positively or negatively.

As a former military member who is still engaged in the military community, the investigator has multiple opportunities for recruitment. The Honolulu Veteran Center, Tripler Army Medical Center, and the Navy transitioning office at Hickam Base are on the list of potential recruitment places. If the experiences of the recruitment center’s visitors result in difficulties with recruiting the veterans who are satisfied with their transition, snowball sampling and alternative sites (in particular, UH) will be considered. Regarding the sample size, it is planned to recruit up to ten people, preferably representing transition-satisfied and transition-dissatisfied participants equally. The considerations of data saturation may result in some changes in the sample size.

Data Collection: Methods and Measures

Semi-structured audio-recorded interviews will ensure the project’s ability to collect relevant data while providing its participants with the opportunity to modify the course of the procedures. This method is very common and especially appropriate for a phenomenology study since interviews are a good source of detailed information about personal experiences (Browne & Braun, 2017; Gray et al., 2016). The topics that are going to be covered include the above-specified factors that determine successful transition and the factors which affect it, especially barriers and facilitators (see Figure 1). These topics can be viewed as the measures of the project, and they are guided by the literature review and theoretical frameworks, especially the recommendations by OSCE (2018) and DVA (2018) (Alarcón et al., 2016; Blackburn, 2016; Kelly, 2016). The data collection tool was developed to reflect these factors, and it and will be pre-tested prior to finalization.

Regarding quantitative data, demographics will include the gender and age of the participants, the number of years that they have spent in the US and in the military, and self-assessed English language proficiency. These data elements can be considered measures since they are measurable; also, the participants’ self-assessed satisfaction with their transitioning will be measured as well. One final element of information that will be collected is participants’ e-mail addresses, which will be necessary for checking the findings.

The data collection site will vary depending on the participants’ preferences, and older people or those with mobility concerns may be visited at their places. However, a private room of a veteran center will be available. Skype interviews will be employed if no face-to-face interaction is possible. Only one interview will be performed with one person, and it should last about one hour, although the procedure might take longer. The interviews will be audio-recorded and later transcribed. It is not planned to check the transcripts with the participants since they are going to be based on audio-recording; instead, the participants will be involved in checking the results of data analysis.

Data Analysis Plan

The demographics information will be summarized (in percentages) to describe the sample. The interview data will be coded with the help of the guidelines described by Tolley, Ulin, Mack, Robinson, and Succop (2016). Specifically, the analysis will be inductive (as appropriate for qualitative research). It will involve the basic steps of reviewing the data to determine potential patterns, coding them, and using their interpretation to develop data-supported themes and theories (Thorne, 2000; Saldana, 2009). The theory that has been developed for the project (see Figure 1) will help to guide the process. Theorization will be continuous; a coding book and memos will be used and updated throughout the process (Tolley et al., 2016). As recommended by Tolley et al. (2016), the analysis will be continuous, iterative, and it will involve several (three) investigators. Their analyses will be compared and negotiated to reach a consensus (Pope, 2000). NVivo software will facilitate the processes of coding and theme development (John & Johnson, 2000). Data saturation will determine the final point in qualitative data collection (Marshall, 1996). Participants will be contacted to check the findings and adjust them if needed.

Procedures

First, the participants will be recruited with the help of plain, informative flyers that correspond to the UH (2019) requirements. The study will be explained, and they will be asked to sign the informed consent form if they agree to participat. Second, audio-recorded interviews will take place; they will last between one and two hours. Third, the data will be analyzed, and the participants will be contacted (with the help of e-mails) again to check the key findings, which will be sent to them as electronic newsletter documents. A revised version of the findings will also require approval; this way, the project will be iterative. Finally, participants will be provided with electronic copies of the manuscript.

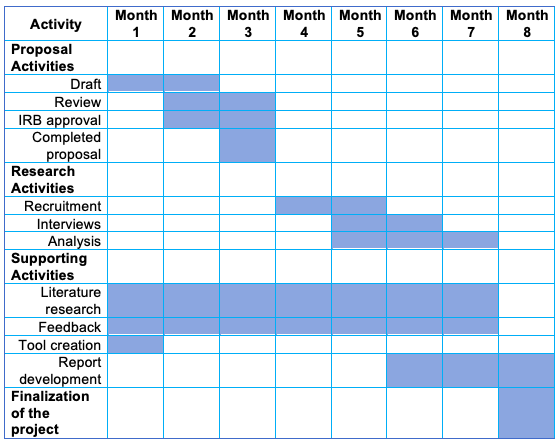

From the researcher’s perspective, the procedures will include literature review, tool finalization, work with participants (recruitment, data collection and analysis, findings verification), and reporting (see Table 1). Additionally, the process of team recruitment is noteworthy. The potential members will be from the University of Hawaii. Just like the participants, they will be recruited with the help of flyers, which will explain the specifics of the tasks associated with the project. The primary requirements will be the participants’ ability to perform data analysis and their familiarity with the NVivo software.

Ensuring Rigor

From the perspective of qualitative research, there exist four aspects of trustworthiness that need to be ensured for a high-quality study. Given the general recommendations on the topic (Gunawan, 2015; O’Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed, & Cook, 2014; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007), the following precautions are included in the present proposal. First, the study is methodologically coherent, which is important for its credibility and dependability (that is, consistency), as well as the ability of future research to reproduce it (O’Brien et al., 2014; Tong et al., 2007). Second, the project will involve a team of investigators; they will be a part of the data collection and analysis processes. An investigator team is a primary requirement for confirmable (relatively objective) findings congruent despite being produced by independent researchers (Gunawan, 2015; Tolley et al., 2016). Third, the researcher will focus on engaging participants rather than studying them, including sharing the findings to ensure that participants agree with the way their words are represented. This way, the subjective nature of the findings will be controlled by multiple people (confirmability), and participants will be empowered to correct the interpretation of their words.

Furthermore, the goal of ensuring thematic saturation is necessary from the perspective of trustworthiness. This way, the likelihood of the project’s findings being representative and transferable increases (O’Brien et al., 2014; Tong et al., 2007). Finally, as a method for detecting and controlling bias, a personal journal will be employed by the researchers, which should promote confirmability and transferability (Tong et al., 2007). In the final report, all the biases and positionality will be included for increased credibility.

Limitations and Their Control; Positionality and Reflexivity

As a qualitative research project that engages about ten people (or less), the project will not make conclusive statements about the described population. However, this small-sample approach is suitable for phenomenology and will ensure a very detailed description of the participants’ experiences (Mayan, 2009). Its findings need to be treated as applicable to the limited group that is being engaged within the community that is being described (Polit & Beck, 2017). This issue cannot be rectified, but it can be mentioned when discussing the findings.

Another problem is connected to recruitment. Due to the topic of the project, self-selection bias is not impossible (Polit & Beck, 2017); it is especially true for the people who do not consider their transition successful or have negative experiences they do not want to relive. To improve the representativeness of the sample, the stratified approach was used; this way, at least several people who are dissatisfied with their transition will be involved.

Furthermore, while multiple researchers will be involved, there is still the risk of subjectivity, which is increased because of the investigator’s positionality. Indeed, it cannot be stated that I, as the investigator, am an outsider to the described population (McCorkel & Myers, 2003). In fact, I share many features with the proposed sample; I was born in the Dominican Republic, grew up in Puerto Rico, and migrated to the US at the age of 19 to become a member of the US military. As a Latino veteran with over 12 years in the military, I can be considered a part of the engaged population in terms of ethnicity and lifetime experiences. This aspect of the described positionality implies the possibility of bias, including the projection of personal experiences onto interviewees, specific perspectives on similar experiences, and a particular understanding of similar events or notions. The recognition of these potential biases is important for reflexivity.

However, biases are a common feature of all humans. Noticing, reflecting on, and controlling biases is important for researchers in any case (Mayan, 2009; McCorkel & Myers, 2003). The methods that are going to be used by this research to reduce the positionality-related bias include triangulation, active involvement of participants, iterative analysis, and reflective journal keeping. The latter is particularly important for self-awareness and self-reflection.

Finally, the data collection tool may be affected by researcher bias, and it may be insufficient for completely capturing participants’ experiences. To avoid such problems, a trial test of the preliminary tool will be conducted with a small number of participants, who will be asked to comment on the tool’s ability to gather data and be sufficiently sensitive and appropriate given the nature of the questions. In addition, the semi-structured feature of the interviews allows some room for additional questions. Thus, the methods of the project do have their limitations, but they are going to be controlled as much as possible and fully disclosed.

Human Subjects and Ethics; Positionality (Research Hierarchy)

The project will require the approval of the Institutional Review Board of the UH. The University of Hawaii Office of Research Compliance (2019) provides templates that will be used to draft the necessary documents, including the informed consent one and the flyer. Overall, the recommendations of the UH (2019) will be the primary guideline for the ethical aspects of the study.

Throughout the research process, multiple ethical concerns can arise. From the perspective of recruitment, it is important to protect the rights of the participants and ensure that their participation is absolutely voluntary. It is especially significant since researchers tend to have some power over research subjects (UH, 2019). For this project, it is planned to view participants as collaborators. So, it is impossible to deny that a level of power imbalance between researchers and participants exists. Therefore, the protection of the participants’ rights and autonomy is of great importance.

First, since the investigator is volunteering for the center that will be the primary recruitment site, recruiting in person could be considered coercive. Instead, plain, informative flyers will disseminate the information about the research by following the requirements of the UH (2019). Interested participants will be able to contact the investigator and request some more detailed information, which will consist of the informed consent document and the opportunity to ask any questions.

The informed consent procedures will explain the project’s purpose and justify it by stating its potential benefits for the population as a whole; the participants will not receive benefits beyond a gift card as compensation for their time. Furthermore, the document will specify all the procedures that are relevant for the participants, including the activities that they will be participating in and all the actions that will be performed with their data. Risks and steps taken to reduce or eliminate them will be detailed as well. The participants’ rights will be stated, and it will be stressed that any questions are welcome and that the refusal to participate is fully possible.

The anticipated risks are unlikely to be severe, and they are probably going to be limited to psychological ones. In particular, participants might experience negative emotions as a result of recounting some of the events. Some of the participants might have psychological concerns, for example, post-traumatic stress disorder, which complicates the situation (Derefinko et al., 2018; Hachey et al., 2016; Pease et al., 2015). To resolve the issue, the informed consent will contain a list of the topics that will be discussed, and the veteran centers that will be used for recruitment will also be used for referring distressed study participants to psychological help. Veterans will be offered brochures with information about relevant services to ensure their safety.

An additional risk is a confidentiality because some demographics data will be required to describe the sample. Still, no participant will be identified by name in any documentation, and pseudonyms will be used. Some of the participants’ statements may appear as quotes in the project’s report; participants will be informed about this beforehand, but the quotes will not be identified. The interview data will be provided to other investigators only during the study. After the analysis is complete, they will resubmit any documents they have, and they will never have access to informed consent documents. All the documents, audio recordings, and transcripts will be preserved, as recommended by the UH (2019), for three years. A secure computer with a password will be used for most of the information. Any physical, paper-based documents will be kept in a locked drawer accessible only to the investigator. All raw data will be destroyed (any paper-based documents) and deleted (any electronic data) after the three-year period expires.

Expected Findings and Future Research

Since the project is meant to discover the lived experiences of participants, the anticipated findings should incorporate the themes that are important for their transitioning, assimilation, and acculturation. Certain themes are anticipated; they include barriers to transitioning and its facilitators, the prerequisites that are required for transitioning, and the outcomes that signify its success, as well as the inequality factors of one’s migrant status and the specific features of veteran experiences. The findings are predominantly meant to inform the activities of social service workers. Still, they might be helpful for developing policies meant to improve the well-being of veterans and migrants.

Regarding future research, the present project does not assume that it will provide exhaustive findings. While the exploration of participants’ lived experiences is likely to yield significant information, it would be possible to proceed in the same or similar direction in the future. Given that the presented project is rather innovative, some of its findings might indicate possible routes for a more in-depth investigation. In addition, more subgroups within the studied population could be discovered. Finally, it is possible to apply a similar methodology to a different understudied population.

Dissemination Plans

As can be seen from the literature review, the question of veteran transitioning is of interest to healthcare, behavioral, and social sciences journals, as well as those focused on veterans (or armed forces), migrants, and Latino or Hispanic populations. The Armed Forces & Society Journal, the Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, and the Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences are among the publications that are referenced in this paper, and they will be considered as platforms for disseminating the project’s findings. The Journal of Veterans Studies is also a suitable option. As an additional dissemination tactic, all the participants will be offered a copy of the final report of the research, which will be e-mailed to them.

Budgeting and Timeline

Voluntary contributions of the investigator’s peers as team members will not require payments, and all the minor expenses (for example, the researcher’s traveling costs) will be self-covered. However, to reimburse the participants’ time and efforts, $50 or $100 gift cards will be offered. Therefore, up to $1,000 will be considered the project’s budget. Also, it is currently suggested to plan an eight-month project. Table 1 was created based on the considerations of how long different research activities are likely to take.

References

Ahern, J., Worthen, M., Masters, J., Lippman, S., Ozer, E., & Moos, R. (2015). The Challenges of Afghanistan and Iraq veterans’ transition from military to civilian life and approaches to reconnection. PLOS ONE, 10(7), e0128599. Web.

Ainspan, N., Penk, W., & Kearney, L. (2018). Psychosocial approaches to improving the military-to-civilian transition process. Psychological Services, 15(2), 129-134. Web.

Alarcón, R. D., Parekh, A., Wainberg, M. L., Duarte, C. S., Araya, R., & Oquendo, M. A. (2016). Hispanic immigrants in the USA: Social and mental health perspectives. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(9), 860-870. Web.

Albertson, K. (2019). Relational legacies impacting on veteran transition from military to civilian life: Trajectories of acquisition, loss, and reformulation of a sense of belonging. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 27(4), 255-273. Web.

Atuel, H. R., Hollander, A., & Castro, C. A. (2018). Racial and ethnic minority service members. In E. Weiss & C. Castro (Eds.), American military life in the 21st century (Vol. 1, pp. 41-53). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Benton, M., & Embiricos, A. (2019). Doing more with less: A new toolkit for integration policy.

Blackburn, D. (2016). Transitioning from military to civilian life: Examining the final step in a military career. Canadian Military Journal, 16(4), 53-61.

Braun, K., Browne, C., Ka’opua, L., Kim, B., & Mokuau, N. (2014). Research on indigenous elders: From positivistic to decolonizing methodologies. The Gerontologist, 54(1), 117-126. Web.

Browne, C., & Braun, K. (2017). Away from the Islands: Diaspora’s effects on native Hawaiian elders and families in California. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 32(4), 395-411. Web.

Cardoso, J., Brabeck, K., Stinchcomb, D., Heidbrink, L., Price, O. A., Gil-García, Ó. F.,… Zayas, L. H. (2019). Integration of unaccompanied migrant youth in the United States: A call for research. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(2), 273-292. Web.

Cathcart, D. G. (2017). Navigating towards a new identity: Military to civilian transition. Canadian Military Journal, 18(1), 61.

Chishti, M., Rose, A., & Yale-Loehr, S. (2019). Noncitizens in the US Military.

Cooper, L., Caddick, N., Godier, L., Cooper, A., & Fossey, M. (2018). Transition from the military into civilian life. Armed Forces & Society, 44(1), 156-177. Web.

Curtis, S., Gesler, W., Smith, G., & Washburn, S. (2000). Approaches to sampling and case selection in qualitative research: Examples in the geography of health. Social Science & Medicine, 50(7-8), 1001-1014. Web.

Daniels, W. C. (2017). A phenomenological study of the process of transitioning out of the military and into civilian life from the acculturation perspective. Web.

Derefinko, K., Hallsell, T., Isaacs, M., Colvin, L., Salgado Garcia, F., & Bursac, Z. (2018). Perceived needs of veterans transitioning from the military to civilian life. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 46(3), 384-398. Web.

Detollenaere, J., Baert, S., & Willems, S. (2018). Association between cultural distance and migrant self-rated health. The European Journal of Health Economics, 19(2), 257-266. Web.

Elnitsky, C., Fisher, M., & Blevins, C. (2017). Military service member and veteran reintegration: A conceptual analysis, unified definition, and key domains. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1-14. Web.

Falconier, M., Huerta, M., & Hendrickson, E. (2016). Immigration stress, exposure to traumatic life experiences, and problem drinking among first-generation immigrant Latino couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(4), 469-492. Web.

Fortuna, L., Álvarez, K., Ramos Ortiz, Z., Wang, Y., Mozo Alegría, X., Cook, B., & Alegría, M. (2016). Mental health, migration stressors and suicidal ideation among Latino immigrants in Spain and the United States. European Psychiatry, 36, 15-22. Web.

Gray, J. R., Grove, S. K., & Sutherland, S. (2016). Burns and Grove’s The practice of nursing research-e-book: Appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences.

Gunawan, J. (2015). Ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research. Belitung Nursing Journal, 1(1), 10-11. Web.

Gupta, M., & Haglund, S. (2015). Mexican migration to Hawai‘i and US settler colonialism. Latino Studies, 13(4), 455-480. Web.

Hachey, K. K., Sudom, K., Sweet, J., MacLean, M. B., & VanTil, L. D. (2016). Transitioning from military to civilian life: The role of mastery and social support. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 2(1), 9-18.

Horyniak, D., Bojorquez, I., Armenta, R., & Davidson, P. (2017). Deportation of non-citizen military veterans: A critical analysis of implications for the right to health. Global Public Health, 13(10), 1369-1381. Web.

John, W., & Johnson, P. (2000). The pros and cons of data analysis software for qualitative research. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 32(4), 393-397. Web.

Kelly, D. R. (2016). Applying acculturation theory and power elite theory on a social problem: Political underrepresentation of the Hispanic population in Texas. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 38(2), 155-165.

Leal, D. L., & Teigen, J. M. (2018). Military service and political participation in the United States: Institutional experience and the vote. Electoral Studies, 53, 99-110.

Maharajan, K., & Krishnaveni, R. (2016). Managing the migration from military to civil society. Armed Forces & Society, 42(3), 605-625. Web.

Marshall, M. (1996). Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice, 13(6), 522-526. Web.

Mayan, M. J. (2009). Essentials of qualitative inquiry. New York, NY: Routledge.

McCorkel, J. A., & Myers, K. (2003). What difference does difference make? Position and privilege in the field. Qualitative sociology, 26(2), 199-231. Web.

Meca, A., Cobb, C., Xie, D., Schwartz, S., Allen, C., & Hunter, R. (2017). Exploring adaptive acculturation approaches among undocumented Latinos: A test of Berry’s model. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(8), 1115-1140. Web.

Ni, S., Chui, C., Ji, X., Jordan, L., & Chan, C. (2016). Subjective well-being amongst migrant children in China: Unravelling the roles of social support and identity integration. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(5), 750-758. Web.

O’Brien, B., Harris, I., Beckman, T., Reed, D., & Cook, D. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245-1251. Web.

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. (2018). Good practices in migrant integration: Trainer’s manual. Web.

Oxford University Press. (n.d.). Migrant.

Painter, M., & Qian, Z. (2016). Wealth inequality among immigrants: Consistent racial/ethnic inequality in the United States. Population Research and Policy Review, 35(2), 147-175. Web.

Pease, J. L., Billera, M., & Gerard, G. (2015). Military culture and the transition to civilian life: Suicide risk and other considerations. Social Work, 61(1), 83-86.

Pedlar, D., Thompson, J., & Castro, C. (2019). Military-to-civilian transition theories and frameworks. In C. Castro & S. Dursun (Eds.), Military veteran reintegration (pp. 21-50). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Polit, D.F., & Beck, C.T. (2017). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (10th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Pope, C. (2000). Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. BMJ, 320(7227), 114-116. Web.

Robbins, S. P., Chatterjee, P., & Canda, E. R. (2011). Contemporary human behavior theory (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Saldana, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Sánchez-Johnsen, L. (2011). The Hispanics. In J. F. McDermott & N. N. Andrade (Eds.), People and cultures of Hawaii: The evolution of culture and ethnicity (pp. 152-175). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

Shaikh, M. A. M., Hall III, J. W., McManus, C., & Lew, H. L. (2017). Hearing and balance disorders in the state of Hawai ‘i: demographics and demand for services. Hawai’i Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 76(5), 123-127.

Terziev, V. (2018). Building a model of social and psychological adaptation. IJASOS – International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences, 4(12), 619-627.

Thorne, S. (2000). Data analysis in qualitative research. Evidence-Based Nursing, 3(3), 68-70. Web.

Tolley, E., Ulin, P., Mack, N., Robinson, E., & Succop, S. (2016). Qualitative methods in public health (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349-357. Web.

Total available active military manpower by country. (2019). Web.

Truusa, T., & Castro, C. (2019). Definition of a veteran: The military viewed as a culture. In C. Castro & S. Dursun (Eds.), Military veteran reintegration (pp. 5-19). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

University of Hawaii Office of Research Compliance. (2019). Templates. Web.

University of Hawaii. (2019). Human Research Protection Program (HRPP): General policy manual. Web.

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2018). The military to civilian transition 2018. Web.

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). Veteran population.

Whealin, J., Nelson, D., Stotzer, R., Guerrero, A., Carpenter, M., & Pietrzak, R. (2015). Risk and resilience factors associated with posttraumatic stress in ethno-racially diverse National Guard members in Hawai׳i. Psychiatry Research, 227(2-3), 270-277. Web.

Wong, M. J. (2017). Culture-bound syndromes: Racial/ethnic differences in the experience and expression of ataques de nervios.