Introduction

Variations in music for every region or locality render identity. Contemporary music has emerged as a mixture of influences from popular to the most minor of ethnic groups so that from time to time, interesting and easily acceptable tunes could become global success in the music industry. This can be said of Latino music such as “samba” and other regional tunes that the consumers of music all over the world enjoy today.

The influence of rock, pop and techno music popularity has also pushed acceptance and mixture of these genre to come up with hybrid tunes, such as Mid-Eastern pop rock and Mid-Eastern techno pop.

Aside from the distinct vocalisation and tune of these hybrid globalised tunes, the use of local instruments in these music performances and productions cannot be ignored. This paper will try to define the Turkish music instruments used in classic and contemporary music as well as provide insight to its role in the presentation of Turkish sound, unique but globally palatable among listeners. It will also include reviews on Ahmet Sendil music with electronic or techno pop and how they produced music to put people in to altered state using traditional Turkish music instruments.

Turkish Music

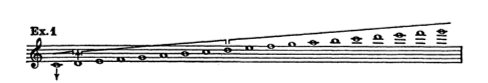

Turkish music is seen as oriental, with variegated intervals less than a semitone incomparable to European music. It is seen as exotic and peculiar. There are two distinct category of Turkish music: classical and folk with consideration to contemporary terminologies. Modern Turkish music is based on the diatonic scale with a compass of two and a half octaves as seen below:

It has a fundamental note scale of D, with very ancient modal construction representing the natural minor scale with a greater sixth.

In Belaiev ‘s survey of the contemporary scale of Turkish classical music, he noted a division of the whole-tone and the semitone without a system to a logical conclusion comprised by intervals of ultrachromatic subdivisions. These small intervals play an important role in Turkish music involving use in melodic writing. The curves and the turns of melodic phrases are based on a conjunct ultrachromatic motion employed in melismata to alter the pitch of the intervals of the diatonic modes which Turkish melodies are constructed. This makes the magnitude of the fundamental diatonic intervals in constructing the different modes possible without sacrificing a mode’s diatonic character. For Belaiev, Turkish music is diatonic even in its most refined classics.

Turkish Musical Instruments

Kemence

There are several classical Turkish music instruments that until today are used by contemporary musicians. These include the Kemence, Ud , and Kanun. The Kemence, a lyre also called keman is the only bow instrument used in Turkey with two types: the pear-shaped kemence and the fasil kemence. It entered the fasil ensemble in the mid-19th century. These are generally now known as classical kemence.

It is about 40-41 centimeters in length with around 14-15 centimeters in width. The strings are made of gut, with the yegah string in silver although today, the synthetic racquet strings or aluminum-wound gut and artificial silk strings or chrome-wound steel violin strings are used. Its sound post is fixed between the bridge and the back of the instrument under the neva string. It transmits sound or vibration to the back of the instrument. A 3-4 mm in diameter is holed at the back of the instrument under its bridge. It is usually adorned.

The word kemence is a Persian word that meant “small bow” or bowed instrument. It was used spike fiddle known today as rebab. It is aid that “The kemânçe gave way first to the viola d’amore and later to the European violin,” (Turkish Music Portal, 2009). Tanburi Cemil Bey is said to have popularized the kemence. He learned using the kemence in Vasil. He soon became a virtuoso and made kemence a “sine qua non instrument” of the fasil emsemble. The kemence was played in taverns and meyhanes for more than a century before it was considered a genuine instrument for Turkish music. It’s sound is perceived to suit Turkish music which has turned emotional and melancholic but the start of the twentieth century.

Huseyin Sadettin Arel devised the polyphonic Turkish music showcasing a five member kemence family comprising of the prototypes of soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, and bass. These have each a set of four-strings of equal length. This has been abandoned but Istanbul State Turkish Conservatory instructor Cuneyt Orhon taught Arel’s soprano kemence so that a three-stringed and a four-stringed kemence are taught separately until today.

Ud

The Ud is another pear-shaped, large-bodied and short necked instrument that belongs to the lute family. It is played in Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Iran, and Armenia. The ud is one of the oldest stringed instrument thought to have been first used in ancient Egypt circa 1320-11085 BC. A bas relief from that period resembles the instrument ud. It was likely made of a single hollowed out piece of wood and smaller than the modern uds and presumed as what the Iraninans use called “barbat”.

By the seventh century, Arabic texts have used the term “ud”. Later Iranian and Arabic text soon used ud, tunbur and barbat interchangeably. It is also believed that Farabi played ud and made modifications on the instrument the most notable of which was the addition of a fifth string previously with only four strings tuned to fourths.

According to the Turkish Music Portal, “The frets that had been preserved until Fârâbî’s time were abandoned toward the end of the 10th century, and earlier players used a wooden plectrum” (2009). It is said that the famous 9th century Andalusian musician used an eagle’s wing feather but today, flexible plastic picks are used. By the later part of the 19th century, the ud has taken a definite place in Turkish classical instruments and used by virtuosos in variety of styles. The ud sound resembles that of western bass guitar.

Kanun

The kanun belong to the kithara class of instruments. It is played in Turkey, North Africa, the Middle East, Iran, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Macedonia, Kosovo and Greece. Organology, which classifies instruments, the kanun is designated as a kithara. The kithara group are composed of instruments with taut strings arranged in an open area producing sound through vibration. The kanun term is used in Turkey believed to have come from the Greek word kanon but with other terms used in Atabic or Greek countries.

The kanun has changed form over time but its basic structure is the same — half trapezoidal shape, with sixty-four strings tuned in sets of three as described bu composer and virtuoso Abdukadir Meragi. It has a range of three and a half octaves played using ivory picks. It is also believed that the Andalusians took the kanun to Europe by twelfth century and used in Spain as caño, canon in France, Kanon in Germany and cannale in Italy (Turkish Music Portal, 2009).

It was introduced to the Ottoman by the fifteenth century and its strucuture has been modified. By the 16th century, Istanbul, Iran and Mesopotamia used identical kanun and constructed entirely of wood with metal strings. Today, only the kalun of the Uygurs resemble this period’s kanun instrument.

Hizir Aga’s Tefhîmü’l Makamât estimated to have been written between 1765 and 1770 also depicts the kanun as known today. During the reign of Mahmud II circa 1808 to 1839, kanun was said to have been played. By the 19th century, women played the instrument. It has become popular and majority of music ensembles feature the kanun. The kanun sound resembles that of western piano or keyboards in dynamism.

Tanbur

The tanbur is considered in Turkey as “the most important plucked stringed instrument of Turkish classical music.” The word is said to have originated from the Sumerian “pantur” used for the long-necked stringed instrument with a half spherical body. It is soon used in Iran and Central Asia for pear-shaped and long-necked instruments resemling the baglama. It is also called tanbura and dombra in central Asia.

The body of the tanbur resembles a half sphere. It is about 35 centimeters in diameter made up of staves of wood glued together. The frets which are tied are made of twisted glut but are replaced by nylon monofilament frets today. Frets range from 45 to 55 although modern tanburs have seven strings. In the 18th century, tanburs have 8 strings with some musicians having customized eight strings today. The tanbur sound resembles that of the western modern rhythm guitar.

Classical and Contemporary Turkish Music

Hall reviewed the first collection of Turkish music called the Master of Turkish Music, compiled by Karl Signell and Richard Spottswood and produced by the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Center for Turkish Music in 1990. It is a compilation of 21 classical, folk, mystic and nightclub repertoires represented, re-recorded from the original 78 rpm discs of companies such as Columbia, Polydor, Victor, HMV and Orfeon. Technically, the perception has been good, the collection considered invaluable with text translations as “excellent, capturing the subtlety and beauty of Turkish poetry (although needs to be) […] organized in a more logical manner.”

There are ten vocal numbers, three nightclub or popular dances, a folk gazel or vocal improvisation, as well as six instrumental improvisations. The vocal numbers include five classical gazel followed by a folk song, a durak or hymn, and three sarkis or light classical songs. Munir Nurettin Selcuk’s mystical durak is followed by the perceived love song by Refik Fresan then a folk dance or halay on zurna, “a jarring juxtaposition […] The listener needs more subtle transitions.”

Hall found the vocal examples of two women: Gulistan Hanim performs a mani or vocal improvisation which is accompanied by zurna, an unusual combination; and Safiye Ayla who sang a classical sarki and a gazel unaccompanied with interludes between lines played on rebab. There were also commentaries with ornamental embellishments as well as Tanburi Cemil Bey’s description of the tanbur taksim. The taksim by Tanburi Cemil Bey is an improvisation using violoncello found to be quite poor, claiming, “We do not need an example of taksim on a western instrument when so many Middle Eastern instruments are under-recorded.”

Ahmet Sendil’s “ Are you Kisses Dynamite?” and “Mi Angel” (original mix) are both electronic or what is commonly known as techno music. It is characterised by a seemingly robotic tune with static. What sets apart Ahmet Sendil’s music from the rest of techno music in popular recording is his use and incorporation of Turkish classical instruments to these modern tunes. The drum machine serves as background as melodic interludes and highlights using the classical Turkish instruments. What is produced are upbeat tunes, danceable and even seductive tunes. The “ Are you Kisses Dynamite?” has a vocal overture of physical and sensual nature that adds impact on the danceable off-beat techno music also laced with Turkish musical instrument sounds.

History

Degirmenci traced political and cultural formation and history of Turkey through its folk music. Accordingly, folk and folklore offer an explanation for the emergence of developmental patterns in cultural and political history of countries that highlight identity. Ziya Gokalp distinguished culture and civilisation as he stated that both Eastern and Western music emerged from Greek music, considered then as something unnatural and artificial as Greek music is based on quartertones.

He proposed that Greek music is monotonous and boring (28). The evolution of Greek music such as the opera by the Middle Ages removed quartertones from the musical structure and added harmony but comparatively, Eastern music remained the same. This was said of the Ottoman music prominent in Turkey. However, by this time, Turkey already had three types of music: western, eastern, and folk also called halk. Soon, Turkish music incorporated both local or folk tune with the Western tune as felt by Ataturk as favourable (Gokalp).

He stated that in the conflict of Eastern and Western music, “these [Eastern music] are inherited from the Byzantines. Our genuine music can be heard among the Anatolian people.” He added that the Turkish people do not have to wait for centuries to develop their music so that magic formula proposed Golkap is a mechanism to reach the musical sphere in the founding years of the Republic.

In the Tanzimat period starting 1826, Western music was introduced to the Ottoman society in Turkey. Geiuseppe Donizetti, brother of the opera artist Gaetano was invited to head the military band od Nizami-i Cedid or the Army of the New Order founded by Selim III. He taught music at the Palace Military Band School or Saray Mizika Mektebi. Western polyphonic music was popularised as famous musicians performed and visited the palace during that period. Sultan Abdulhamit II is said to have claimed, “I am not especially fond of alaturka music. It makes you sleepy, and I prefer alafanga music, in particular the operas and the operettas. And shall I tell you something? The modes we call alaturka aren’t really Turkish. They were borrowed from the Greeks, Persians, and Arabs.”

Alaturka then is viewed as alien to Turkish culture. Subsequently, Musicians trained in musical schools at this period based on the principles of Western polyphonic music and adoption of the Western-style notation. One kind of music is performed at the palace, another among the reural folks unknown to the palace circles, and the music of the tarikats or the Sufi religious order called tekke or lodge music.

The Republic closed down the schools of music from the Ottoman empire in order to establish their own identity by 1924. Even the lodges and cloisters called tekke ve zaviyeler considered as the centres of tekke music were also abolished and by 1934, art music was banned in radio stations for two years. In 1935, Paul Hindemith was invited by the Republic to establish Western musical education and performance in the Ankara School of Music.

Folk songs and music from the Anatolia region were collected to establish a small museum of ethnography. The Ministry of Education appointed the brothers Seyfeddin and Sezai Asal to collect about hundred tunes from Western Anatolia, and Yurdumuzun Nameleri or Melodies of our Country was published in 1926.

Conclusion

Turkish music has evolved over the long course of history. As already established, there has been a global exchange of musical instruments, influences and other forms of sharing amongst ethnicities even in the ancient period so that one instrument found in one locality may have a slightly differing version in another. This can be said of the Turkish classical music instruments.

Their acceptance in the Turkish music ensembles are in themselves a story of their own but the music instruments discussed here, the umence, ud, tanbur and kanun are used to their fullest musical prowess until today as exemplified by the music of Ahmet Sendil. While even a sultan denied the melancholic and sleep-inducing Turkish music that has been embraced by a nation, Turkish music has evolved to take other forms aside from the previously sad overtures that were performed in a long period of the Turkey history. The emergence of modern electronic or techno pop are musical testaments that cannot be denied amongst listeners, within Turkey or outside of it.

References

Bartok, Bela. 1976. Turkish Folk Music from Asia minor (ed. By B. Suchoff). Princeton University Press.

Stokes, M. The Arabesque Debate. Music And Musicians In Modern Turkey. 1992.

Degirmenci, Koray. 2005. “On the Pursuit of a Nation: The Construction of Folk and Folk Music in the Founding Decades of the Turkish Republic.” International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, Vol 37, pp 47-65.

Gokalp, Ziya. Turkculugan Esalari (The Principles of Turkism), 1978, Inkilap ve Aka.

Victor Belaiev, S. W. Pring. 1935. “Turkish Music.” The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 356-367.

Hall, Leslie (Review: [untitled] Leslie Hall Reviewed work(s): Masters of Turkish Music by Karl Signell; Richard Spottswood; Center for Turkish Music, The University of Maryland Baltimore County Asian Music, Vol. 22, No. 1 (1990-1991), pp. 166-167.

Turkish Music Portal. 2009. “Instruments.” Turkish Cultural Foundation. Web.

Sendil, Ahmet. 2009. “ Are you Kisses Dynamite?” and “Mi Angel”. (original mix) Youtube. Web.

Saygun, Adnan A. Ataturk ve Musiki: O nunla Birlikte, O’ndan Sonra [Ataturk and Music: With Him and After Him. A987, Ankara: Sevda Cenap Muzik Vakfi Yayinlari: 1, 9.

Tekelioglu, Orhan. 1996. “The Rise of a Spontaneous Synthesis: The Historical Background of Turkish Popular Music.” Middle Eastern Studies 32, 1, pp 194-216.