Introduction

The Problem

The global problem of drug use continues to pose a serious threat to health, safety and well-being of humanity. Today, drug addiction among children and youth is of particular concern. The United States is one of the countries where the most critical situation shaped in this area. As of 2017, 23 million Americans suffer from drug addiction, and only one in ten receives qualified treatment (Goldberg & Mitchell, 2018).

Epidemiology of the problem

Overdose of drugs, mainly opioids, kills at least 190,000 people every year (Bolliger & Stevens, 2019). Most of them are young people. The largest number of drug addicts is in the United States – 28.6 million people aged 12 and over (Goldberg & Mitchell, 2018). In addition, the spread of drugs is showing a steady growth trend; its adverse consequences are very multifaceted both for the drug addicts themselves and for the society in which they exist.

Purpose of the project

In this regard, the purpose of this work is to analyze drug use in the United States in retrospect and at the moment, as well as overall social implications of this problem, history of war on drugs, its effectiveness and prospects.

History of Drug Use in USA

American attitudes toward drugs use have taken a dramatic turn. A drug can be defined as “a medicine or other substance which has a physiological effect when ingested or otherwise introduced into the body” (Maisto et al., 2018, p. 14). In the 19th century, certain psychotropic substances, such as opiates and cocaine, were often considered useful medications. Until the 19th century, drugs were used in their natural form: for example, cocaine and morphine contained in coca leaves or opium poppy flowers were available, and therefore they were chewed, dissolved in alcoholic beverages or consumed in such a way that the effect of the active substance was weakened. With the development of organic chemistry in the 19th century, the forms of drug use changed. Morphine was isolated in the first decade of the 19th century, cocaine – around 1860, and diacetylmorphine was synthesized from morphine in 1874 (Belenko, 2000). By the middle of the 19th century, the hypodermic syringe was structurally improved, and by the 1880s it became a familiar tool for American doctors and their patients (Belenko, 2000). The rapid development of the pharmaceutical industry at that time contributed to the rapid spread of both new drugs and new instruments.

During this period, due to the peculiarities of the American constitution, potent new forms of opium and cocaine were more available in the United States than in most other countries. Under the constitution, states take responsibility for matters such as health care, medical care, and the provision of pharmaceuticals. In practice, it means that each US state has its own law governing the activities of the medical profession. For much of the 19th century, many states chose to relinquish any control over this area.

In the 19th century, per capita consumption of unprocessed opium gradually increased and peaked in the past decade. Then it declined, but according to data from the period after 1915, it is no longer possible to notice any trend in drug use, since that year, legal imports of this product were severely restricted by new federal laws (Goldberg & Mitchell, 2018). In contrast, per capita consumption of smoked opium increased until 1909, when the import prohibition law was passed (Goldberg & Mitchell, 2018). Americans quickly adopted the habit of smoking opium from Chinese immigrants who came to the country after the civil war to build railways. In the first third of the 20th century, cocaine was likewise associated with African Americans and marijuana with Mexicans.

Impact of Drug Use in the USA

In the 19th century, increasingly more people became influenced by opiates – substances that needed to be taken regularly, and as drug use increased, more people became addicted. However, at first, neither the doctors nor their patients suspected that the appearance of a hypodermic syringe or pure morphine potentially posed a danger of addiction. On the contrary, it was believed that since pain can be relieved by injections with less morphine, the likelihood of addiction to the drug decreases.

The history of cocaine use in America is somewhat shorter than that of opium, but it followed a similar scenario. In 1884, refined cocaine became available commercially in the United States. At first, its wholesale price was very high at $ 5-10 per gram, but soon dropped to 25 cents per gram and remained at this level until the inflation period during the First World War (Goldberg & Mitchell, 2018). The problems with cocaine were evident almost from the beginning, but both the public and leading medical professionals considered cocaine to be harmless and a good stimulator.

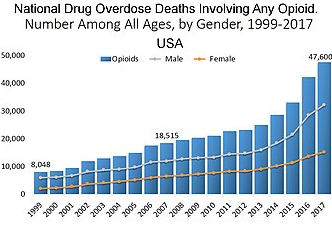

Heroin use as a social problem has also risen sharply among all demographic and socioeconomic groups: men and women, rich and poor, educated white-collar workers, and people who have not even graduated from school have become addicted to it. Heroin overdose deaths increased by 286% between 2002 and 2013 (Goldberg & Mitchell, 2018). It should be borne in mind that heroin is usually injected, and this puts addicts at risk of developing serious infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B and C, skin infections, etc., which represents personal problems. Moreover, drug abuse leads to deviant behavior in addicts and raise of crime rates in communities. The third wave of the opioid crisis hit in 2013, with an increase in mortality associated with synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. The sharpest jump came in 2016, with more than 20,000 deaths from fentanyl and its structurally related drugs (Cowles, 2019). Alarming dynamics of drug overdose deaths in the period of 1999-2017 is shown on the graph below.

Drug overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States today. According to expert estimates, over the next ten years, about 500 thousand people may die from opioid overdoses in the United States (Graeme, 2017). Opioid dependence in the country has become a real epidemic.

History and Development of War on Drugs

The roots of the war on drugs in the USA go back to the 19th century, and the first attempts at an organized fight against drug use in the country date back to 1914, when Congress passed a law proposed by the representative from New York, Francis Harisson. The fight against drugs continued after the First World War, but the number of drug addicts in the United States increased dramatically: many soldiers became addicted to morphine on the fronts (Goldberg & Mitchell, 2018). It is significant, however, that the motives for the fight against hemp production were largely economic (in part, the laws against hemp producers were lobbied by wood-based papermakers who feared competitors) – and were easily canceled if necessary. After World War I, the British and American governments came up with a proposal to include the Hague Convention in the Treaty of Versailles. Therefore, the ratification of the peace treaty meant the ratification of the Hague Convention; as a result, the countries-parties to the treaty had to introduce anti-drug laws.

In the second half of the 20th century, politicians decided to use the term ‘war on drugs,” implementing a new approach both at the legislative level and in the struggle for the minds of citizens. The administration of US President Nixon ushered in a new era of drug control. Shortly after taking office in 1969, Nixon launched a global campaign to eradicate drugs and drug dealers. He launched Operation Intercept, ordering the blockade of 2,500 miles of the border with Mexico and the search of hundreds of thousands of people and vehicles (Cowles, 2019). In 1970, Nixon established the National Committee on Marijuana and Drug Abuse. In 1971, he declared drugs public enemy number one; all these actions meant unleashing a national and international war against drugs.

The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 was another historic turning point in America’s attitudes toward illegal drug regulation. This Act completely replaced Harrison’ Act as the federal government’s primary domestic drug control instrument. He reformed all pre-existing anti-drug laws with regard to federal powers to regulate interstate commerce, and established a system that categorized drugs based on their potential for abuse.

However, the efforts made by the government yielded meager results, and the credibility of politicians in society was undermined by the Watergate scandal and the unstable political environment. Unsurprisingly, this situation only got worse: from 1978 to 1984, cocaine consumption in America increased from 19-25 tons per year to 71-137 tons (Mallea, 2014). The ‘tone’ of the federal approach to illicit substances changed slightly during the brief period in power of the administration of President J. Ford, which showed some pragmatism in drug trafficking issues. In practice, President Ford continued to use harsh anti-drug measures, but he did so based on the belief that drug addiction will always remain a problem, and the hopes of eradicating it are completely illusory.

President R. Reagan, taking office, treated illegal substances in much the same way as his predecessor Nixon a few years earlier. In the 1980s, Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign reached out to the entire country, especially parents, schools, and the media. President Reagan took a tough stance on drug law enforcement, in some ways repeating the tactics used by President Nixon. In 1982, the White House launched a coordinated operation in southern Florida to combat the illicit drugs that flooded the state. Between 1983 and 1985, the government spent millions of dollars in seizure of thirty tons of cocaine and 1,500 tons of marijuana (Mallea, 2014). Despite the massive prohibition, drug use increased significantly during this period.

The fight against drugs has been one of Bush’s priorities since his presidency in the 1980s, and as president, he decided to place it at the center of his political agenda. In the months that followed, the president signed several laws that severely toughened punishment for drug trafficking, including Program 1208 (now known as Program 1033), which ordered the supply of heavy military weapons to local police forces. Thus, a new round of the war on drugs began – more decisive than many previous attempts in American history, and more impressive in its failure (Goldberg & Mitchell, 2018). Police officers, armed like the military, have become common on the streets of many American cities; mass raids and arrests of small drug dealers became commonplace, and the stigmatization of drug users in the media did not surprise anyone.

Bush has decided to allocate an additional two billion dollars to combat drugs in Colombia. Bogota in the 1990s (already under Clinton) was ‘flooded’ with CIA agents, and over ten years the United States spent about ten billion dollars on the fight against the Colombian left-wing guerrillas from the FARC, as well as on the struggle with drug cartels; the program was curtailed already during the time of President Bush Jr. Later, a similar plan for organizing the fight against drug trafficking was developed for Mexico, and it is being implemented today.

Current War on Drugs Strategies

The war on drugs has been going on in the United States (and beyond) for more than fifty years, although its intensity has decreased due to the growing threat from international terrorism. However, the results are equivocal; police and immigration services services themselves admit that they are capable of intercepting from ten to thirty percent of heroin and cocaine trafficking; huge spending on fighting actually goes nowhere (Cowles, 2019). During the years of the war on drugs, America has loaded its jails with prisoners so much that it is no longer able to maintain them. Therefore, since 2008, it has purposefully released them while still leading the world in the number of prisoners. The initial targeting of consumers led to the fact that a huge number of people were thrown into jail – for the sake of achieving a quick result ‘here and now.’ More than 80% of arrests are related to the possession, not the distribution of drugs; however, large drug dealers fell into the hands of law enforcement officers much less often. If to consider the US anti-drug legislation as a whole, then it is very voluminous and contains a lot of legal subtleties. In particular, there are laws prohibiting the manufacture of drugs, the possession and sale of items used to make drugs and their introduction into the human body, although in ordinary life situations, the use of such items is legal. The main approach of federal legislation to combat drug trafficking is the prohibition of a number of types of acts associated with drug trafficking – (1) production, (2) possession with intent to distribute, and (3) distribution of “substances under control”

In recent years, there were attempts in the United States to develop other anti-drug strategies besides policing. However, this is still not enough – the country is now experiencing a real opioid epidemic: 130 people die from drug overdose every day, almost a million use heroin, and 12 million abuse prescription opioid drugs (Bolliger & Stevens, 2019). US President Donald Trump has declared opioid proliferation and overdose deaths a national disaster. The launched campaign is part of the Department of Health and Human Services’ 5-point strategy to combat the opioid epidemic in the United States. This strategy includes the following components (Bolliger & Stevens, 2019):

- Improving access to prevention, treatment and recovery services, including a full range of medical procedures;

- Focus on the availability and distribution of drugs to combat opioid overdose;

- Improving understanding of the opioid crisis by raising the quality of public health data and reporting;

- Providing support for advanced research in pain and drug abuse research;

- Promoting the best pain management methods.

Discussion

Winning the war why

Despite the efforts made, the problem itself remained unresolved. In 2017, about 50,000 Americans died of drug overdose, and about five times more than in 2000 (Cowles, 2019). Although the war on drugs has achieved some of its goals, the most important task – to seriously reduce drug use in the United States – remains a dream: the share of drug users has only increased since 2000 (Cowles, 2019). Thus, it is not surprising that since the early 2000s, one can hear more that the war on drugs was lost. At the same time, analysts were inclined to believe that the tightening of responsibility for drug trafficking has a short-term effect that lasts no more than two years: after that, arrests no longer have such a negative effect on drug trafficking and drug use (Cowles, 2019). At the same time, the therapy programs in the long run seemed to researchers the most effective approach, the only drawback of which is the very slow achievement of the result.

Losing the War

Nevertheless, the number of overdoses of illegal synthetic opioids, on the contrary, continues to grow. The opioid epidemic in the United States is one of the reasons for the decline in life expectancy. However, it is not just about drugs, but the whole complex of problems that in the United States are called “diseases of despair.” People between the ages of 25 and 64, predominantly working class, die at a higher rate from obesity, heart problems, as a result of suicide, and liver disease associated with alcohol abuse. Experts attribute these phenomena to a growing social crisis and increasing inequality (Cowles, 2019). Victims of “diseases of despair” are more likely to experience stress due to financial difficulties, cannot afford adequate medical care, and do not see the economic prospects.

Suggested Strategies for Winning the War

Currently, the United States is studying the possibilities of using three concepts of combating drug addiction. The first concept provides for the activation of the traditional model: an all-round and extremely tough fight against drug traffickers and drug producers, including outside the United States, and the tightening of anti-drug legislation. Critics of this approach argue that it is impossible to completely eradicate drug addiction, since drug use has always been a “shadow” of civilization.

The second concept focuses on reducing drug use. In particular, the emphasis is supposed to be made on strengthening explanatory work. Drug traffickers should be punished as severely as possible, but people caught using or possessing drugs should not be severely punished. Critics of this strategy argue that promoting healthy lifestyles does not significantly reduce drug use.

The third concept proposes to change the approach to drug addicts – they should be viewed not as criminals, but as patients who should not be punished, but treated. The state must decriminalize drugs – make them legal, which will allow controlling their sale and prevent drugs from falling into the hands of young people. Moreover, this strategy can reduce the power of criminal gangs. Opponents believe that the availability of drugs will only contribute to their wider distribution, and there are still no methods that can guarantee drug addicts’ freedom from the addiction.

However, given the growing social inequality, acute social conflicts and the above-mentioned “disease of despair,” it seems advisable to competently combine the above strategies, taking into account regional differences in states, as well as focus on solving social problems. The fight against drugs alone, without a social orientation, is not able to bring tangible results, since in this case it looks like a fight against “symptoms” and not “disease.” It should be borne in mind that in individuals and groups, as well as within the framework of different behaviors, different behavioral deviations can be observed. One of the key takeaways from the behavioral sciences is that one-size-fits-all solutions don not work. In other words, behavioral interventions should be as targeted and individualized as possible: appropriate interventions should be designed for a specific target group taking into account the specific behavior that needs to be encouraged or discouraged.

Summary and Conclusion

Over the past 100 years, drug addiction from a problem that was the subject of a narrow field of medicine – psychiatry – has moved into the category of general social problems. In the modern world, including the United States, there is a continuous trend towards an increase in the number of people taking narcotic drugs, drug use by young people is increasing, and representatives of all socio-economic groups of society are involved in drug abuse. Retrospective analyzes and research on current war on drugs strategies have shown very little, if any, effectiveness. Based on the study of the current situation and possible strategies, it was concluded that group and individual prevention is an extremely important area in the fight against drug addiction. In this regard, the provision of a preventive effect on dysfunctional families, groups, collectives, and so on, is of particular importance.

References

Belenko, S. (2000). Dark paradise: A history of opiate addiction in America. Greenwood.

Bolliger, L., & Stevens, H. (2019). From opioid pain management to opioid crisis in the USA: How can public-private partnerships help? Frontiers in Medicine, 6, 106.

Cowles, C. (2019). War on us: How the war on drugs and myths about addiction have created a war on all of us. Fidalgo Press.

Goldberg, R., & Mitchell, P. (2018). Drugs across the spectrum (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Graeme, D. W. (2017). The opioid epidemic of America: What you need know about the opiate and opioid crisis. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Maisto, S., Galizio, M., & Connors, G. (2018). Drug use and abuse. Cengage Learning.

Mallea, P. (2014). The war on drugs: A failed experiment. Dundurn.