Introduction

Rationale for the study

Significant progress has been made over the years to attain gender equality at the workplace. As a result of combined efforts between governments and nongovernmental organizations, the number of women in the employment sector has increased significantly. A research by the International Labor Organization further reveals that there is a psychological phenomenon that characterizes job as either fit for men or women and that the number of women who are streaming into jobs that were traditionally reserved for men is also increasing as well (ILO 2003). Access to education is one of the key factors that lead to the increase of women in labor force. According to a survey by the Intentional Labor Office of the International Labor Organization, the number of women in the job market has increased progressively over the years from 36% in the 1960s to over 40% in the 21st century (ILO 2003).

Concurrently, access to education by women has increased over the years, as well as the level of performance by women over men in academics. Furthermore, the number of enrollment of women in institutions of higher education has also increased. A report by the United Nations on education in 85 of its member nation’s show that the number of women outstrips men in the attainment of graduate and post graduate degrees. 56% of Master’s graduates are women while the number of women graduates has outstripped men by 2 percentage points globally (UNESCO 2010). Currently some countries such as the United States of America record higher number of women than men in the labor force. In 2010, women constituted about 56% of all workers in the US (US department of Labor, 2010). However, statistics on the number of women who hold management and other senior positions reveal disturbing realities. Women hold less than 30% of middle and senior level management positions globally (ILO 2003). This shows that there are factors that hold women from advancement to top management level positions at the work place.

This reality ascertains the commonly held belief that women do not have the same opportunities as men at the job market as they hold fewer positions (IFC 2009). It therefore holds that the ‘glass ceiling’ phenomenon for women is real in today’s corporate world. The term glass ceiling emerged in 1986, a description by the Wall Street Journal that there is an unseen force that seems to hold women from attaining their highest potential in the job market (Hymowitz & Schellhardt 1986). The article hypothesized that there are traditionally held beliefs, prejudices and notions in the corporate world that acted as stumbling blocks to women progress and rise to the highest step of the cooperate ladder. Consequently, the term became so popular and gained a global acceptance in describing all the obstacles that women face as “those invisible, culturally embedded assumptions and beliefs about the skills and competencies of women that prevent their advancement into top management positions or their advancement into certain communities and domains like engineering or technical occupations” (Eriksson-Zetterquist & Styhre 2008).

So real and widespread was the phenomenon that it became officially recognized by the United States government. Consequently, the Federal Glass Ceiling Commission, which is a 21-member commission, was formed in 1992 to identify the specific barriers that hinder the progress of women as well as minority men to the decision-making positions in the job market. Furthermore, the commission was mandated with the responsibility of identifying steps that will help to overcome the glass ceiling phenomena (Federal Glass Ceiling Commission 1995).

The reality that the glass ceiling exists and the influence it has on the rise of women to top positions has led to extensive research. Most of this research is general and is not industry specific. A survey by the International Labor Organization in 2004 studied the situation of women in the labor force. The research evaluates the role of women in professional and managerial jobs in a general way. The research just highlighted the statistics of women involvement in the labor market without giving the implications or the causes of those statistics. Furthermore, the study was conducted between the years 2001 and 2003 and did not specify statistics by industry (ILO 2003). However, this is not to mean that industry specific studies are absolutely missing. A survey by U.S. Census Bureau reveals that the number of women who have attained degrees in the hospitality industry has increased over the years.

The research shows that up to the year 2004 the number of women who had enrolled in both graduate and post graduate level of education in hospitality related courses has increased by 41%. The study further shows that despite the increase in attainment of doctorate degrees by women by up to 35% there was no corresponding rate of increase in the number of women who held high level jobs in the industry (U.S. Census Bureau 2005). The study however, comes short of describing the actual reasons that do influence these discrepancies. A similar research by Bonnie J Knutson and Raymond S Schmidgall from the Cornell University evaluate s the dimensions of glass ceiling in the hospitality industry. The survey categorizes the dimensions into three broad areas namely personal career advancement, women personal characteristics (personality types) and the company’s strategies for recruitment.

Knutson and Schmidgall surveyed and collected data from 234 women in top management positions in the hospitality industry to come up with conclusions (2010). The respondents agreed that they do acknowledge that they have faced a number of challenges in their career, which at times hindered their career progress. The survey shows that a combination of the three broad dimensions keeps women from advancing at the same rate as their male counterparts in the entire hospitality industry. However, the survey does not break down the findings to the specific sub categories of the entire hospitality industry. It does not also show the chances of women in different categories of jobs such as lower level jobs, middle and general management positions in sub categories of the hospitality industry such as travel, hotel and restaurants. Barrows (1999) defines hospitality as “any and all businesses and devices, which include hotels, restaurants, guest houses, resorts, travel services, conference facilities, whose primary objective was serving people outside of a private home.”

The aim of this thesis is to explore the reasons why women have lower level of career success than men in the hotel industry especially in middle and general management positions. From previous research it has been found out that a number of factors do hinder the rise of women to top management positions in the hospitality industry. Thus in relation to the study of the glass ceiling phenomenon regarding the hotel industry, several questions beg. Is the occupation of middle and general management position in the hotel industry affected by personality differences, is it affected by the specific company’s hiring strategies or is it affected by the individual’s personality and/or career strategies. As such the general guiding question that will help cover this thesis is: why do women lag behind in the occupation of middle and general management positions in the global hotel industry. The thesis question is further broken down into several sub questions all of which will answer specific aspect of the thesis question. The sub questions are as follows:

- What are the general characteristics of the global hotel industry including employment statistics?

- What barriers hinder the occupation, by women, of middle and general management positions in global hotel industry?

- Are there counter strategies that would help break the glass ceiling?

Reason for choice of topic

The hospitality industry is one of the highest employers in the world. This industry attracts a very high number of workers with varied abilities, qualifications and skills due to the dynamism of the industry and its requirements. The high number of job in the hotel industry is also aided by the fact that the industry has embraced latest technologies, which facilitates even further growth of the industry. Furthermore, technologies ensure that the recruitment exercise in the industry has become easier as it helps industry players to cast their nets wider in search of qualified personnel. Technology has lead to continued globalization which facilitates easier movement of labor force around the globe (Choi, Woods & Murrmann, 2000).

This therefore means that the industry offers numerous job opportunities. Women make deliberate choice in pursuing career in the hospitality industry a compared to men. This is evidenced by a survey by U.S. Census Bureau (2005) which shows that there is a higher number of women who are graduating at both the graduate as well as post graduate level with hospitality industry related qualifications (Becker 1985; Billy & Manoochehri 1995). King (1995) reports that women do experience the same level of success as men at all levels of education. Loutfi (2001) and King (1995), add that women who hold the same job description as men have higher qualification than men. Despite this finding, the number of women in middle as well senior management positions is way below the number of women graduates with qualifications in hospitality management.

There are a number of assumptions that lead to this. Traditionally women are seen as the child bearers. This role hinders their career growth. This is because of the traditional notion of the biological clock phenomenon which scares women as they approach a certain age to bear children. As such women feel the urge to bear children, at between the age of 30 and 40. Coincidentally, this is the age at which they have to set the pace for career growth and progress. As such they have to make tough choices on whether to sacrifice family or career growth (Gordon and Whelan-Berry 2005).

Furthermore, traditionally married women have taken more domestic roles. As such women have with time been required to stay at home and take care of their families while husbands, to support their families, are allowed in many societies to seek employment. Success of men at the work place is measured by the amount of time spent working while for women success is measured by the amount of time spent taking care of the family.

As such these two roles, career progression and family care have been masculinized and feminized respectively (Martin & Meyerson 1998: Becker1975). The kind of perception about the role of men and women is still held strongly today. The fact that men are traditionally the bread winner means that they assume certain behavior such as assertiveness, controlling and independence while women roles as caregivers mean that they assume different behaviors such as emotional connectedness, relationship and friendship building as well as care giving (Guadagno & Cialdini 2007; Becker 1985). As such men take leadership roles at home as well as in the society while women play supporting roles. Suffice to say that women have thus learned to give way to men. These findings are explained in details within the social roles theory which stipulates that both men and women have different social roles; men are seen as the provider while women are seen as the care givers (Eagly 1987). This notion of gender roles is later in detailed examined in literature review and how it affects career progress for women in the hospitality industry.

The study for this thesis is conducted in reference to the global hotel industry. This industry is as part of the wider hospitality industry which is very demanding in terms of involvement by employees. Unlike in most of the other industries where employees work normal hours, mostly between 8:00 am to 5:00 pm, the hotel industry demands 24 hour engagement by employees as they have to attend to clients round the clock. This means that employees are required to work for long and sometimes odd hours. This compromises the role of women who are seen as caregivers as they are expected to spend long hours away from their family responsibilities, to fulfill career responsibilities. As such, women have to constantly juggle career and family (DuBrin 1994; Bierema 1998). Because working odd hours leaves families unattended, women thus chose family over working odd hours. When this is analyzed Vis a Vis the glass ceiling phenomenon it puts the place of women in the hotel industry in even more jeopardy.

Research Methodology

The following methodology of the research is set to exhume valuable data about the chances of women progressing in middle as well as senior level positions in the global hotel industry. To arrive at conclusions, the research needs primary data from a number of global hotels. Because the study aims at unveiling the complexities of the glass ceiling phenomena, a qualitative research will be undertaken. This will involve having detailed interviews with global hotel managers at both middles level as well as senior level positions. The methodology will first aim at identifying whether women are aware of any barriers that hinder them from ascending to top position in the global hotel industry. To test the prior knowledge the interview will employ both close ended and open ended questions. Open ended questions are designed to account for additional information that will be crucial to the study.

Hollin (1995) explains that personality affects perception and as such each of the interviewees will be required to undertake the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, a personality test that reveals the suitability of each of the interviews personality for a particular job roles. Results from this test will help to explain how personality types affect their career progress (Jones 2011). To account for information about individual woman career progress strategies each of the interviewees will be asked to produce their curriculum vitae, which will be used to identify whether they have had a clear and explicit career growth strategy prior to this study.

The purpose of requesting for a CV is to identify whether the interviewees have made deliberate effort to identify career paths and thus avoid interviewees giving false information. The result will be combined to show the correlations between women awareness about possible barriers, the actual barriers that does exist and that how personality affects the occupation by women of middle and senior level management job in the global hotel industry. Furthermore, the finding will also help identify ways to counter the glass ceiling effect as well as provide basis for future research.

Overview of chapters

This thesis paper is divided into two main parts. The first part is comprised of chapters 1, 2 and 3. Chapter 1 is the introductory section that gives a brief overview as well as background information on the thesis. Chapter 2 and 3 is the literature review. Chapter 2 gives background information on the global hotel industry especially in the recruitment and occupation of middle and senior level management position by women. Chapter three evaluates related literature about the awareness of women of any barrier that exist to hinder their career progress. These are also evaluated Vis a Vis the social roles theory which stipulates that the genderization of society roles does have an effect in the career progress of women. Part two of the paper is comprised of chapters 4, 5 and 6. Chapter 5 is the research methodology design, population as well as design section. Chapter five concludes the thesis while chapter 6 gives recommendations from the findings of the research.

The global hotel industry

A brief history

The concept of the hotel can be trace back to antiquity, with the idea emanating from the concept of renting out space for travelers. Therefore, there emerged a class of people who could offer boarding space as well as food within their private homes to travelers (IRS 2007). The history of the hotel industry cannot be alienated from the larger hospitality industry. The French term hospice is the root origin of the term hospitality which means to “provide for the weary and those traveling”. Early hospitality is characterized by Greco-roman travelers, who made long journey for religious as well as business purposes as early as 40 BC. During the medieval period, Inns evolved as public places of boarding in England as a result of the appreciation of the British hospitality. High demand for boarding and food by travelers led to the construction of the first known hotel, Hotel de Henry. The idea spread to many other parts of the world. Currently there are many world class hotels such as Hilton, The Ritz, Intercontinental, among others (Miller n.d). The global hotel industry is divided into major categories such as:

- Commercial Hotels, which are set with the business traveler in mind

- Airport Hotels, set near airports and cater for business travelers. They may offer transport services to and from the airport.

- Conference Centers, established to provide catering for meeting, conferences and conventions

- Economy Hotels, established to provide low, prices services. Due to the low prices they offer limited services

- Suite or All-Suite Hotels: they provide exclusive services which include transport, boarding, meals, private meeting places. They are high priced.

- Residential Hotels established to offer accommodation and meals on long term basis

- Casino Hotels established to carter for the gambling clients. They offer excellent and high priced services

- Resort Hotels located on beaches or around mountainous regions, far away from urban centers. They provide accommodation to tourists (IRS 2007)

As of the year 2002 Vargas & Aguilar (2002) explains that women constituted up to 42 % of labor force in the global hotel industry. This is due to the vertical and horizontal gender segregation in this industry and as such there exist gender disparities within this industry (Zhong 2006). This reality is much more evident in middle and senior level management positions. The number of women who hold these positions is quite low despite the recent indications of change. However, the rate of change is too low to be any significant (BBC 2007). This is despite the fact that there women are equally, sometimes better educated and qualified than their male counterparts who hold the same positions globally (UNESCO 2010) which means that women make deliberate choices to pursue careers in the hospitality industry. Yet, women continue to hold fewer positions, especially in middle and senior management positions due to what the social roles theory explains as influences gender roles on women career advancement. This is explained in details later in this paper.

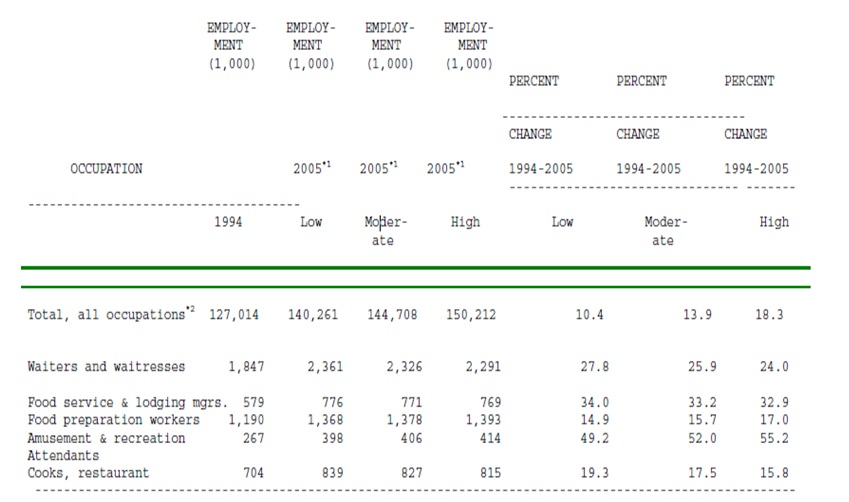

The hotel industry accounts for a significant percentage of jobs in any economy. Because the industry is expected to grow the number of jobs is also expected to grow at the same rate. This means that the number of positions within which women qualify will also increase. This is because of the latest tends in the employment statistics seen in the table 2.1 below. The question thus is will the glass ceiling effect continue to affect women occupation of middle and senior level job in the hotel industry?

Social roles and the glass ceiling

Introduction

This chapter is the final part of the theoretical foundation that explains the barriers that women face in advancing to middle and top level management positions. It offers detailed insights into the reasons why women lag behind in career advancement. In relation to this, three dimensions of the glass ceiling phenomenon will be discussed, and how they have a bearing on relating to the main thesis question. The three dimensions are individual personalities, the corporate hiring strategies and notions and the specific women career progress strategies. Within this chapter, the social roles theory will be explored in details.

This theory stipulates that in many societies all over the world, men and women have specific social roles. Men have traditionally taken the providers roles and thus venture out in search of gainful employment. This empowers them economically and as such gives them power to take control-ship of their families and eventually the society. As such men have over time taken leadership roles. Meanwhile, women have taken domestic roles in the family such as child rearing, and family care giving. As such, they have had to stay at home most of the times. This has implications in the way their roles are perceived career wise. Due to the social roles that women take, they have also adopted certain behaviors, which too have a bearing on their career roles as well as career progress. All these are explored Vis a Vis the glass ceiling phenomenon especially in the global hotel industry. Finally, a general conclusion will be offered.

The glass ceiling phenomenon.

The term ‘Glass Ceiling Phenomenon’ was first used by a woman columnist in the Wall Street Journal in 1986 to metaphorically describe a set of unseen, yet impenetrable barriers that have hindered the advancement of women to the top most positions in the corporate world, in spite of their skills, educational qualifications as well as other accomplishments. The phrase was immediately taken by journalists, leaders in business as well as policy makers. The plight to minority men was also added to the definition after extensive research, which indicated that some men from minority groups also faced similar hurdles as women in their career paths. A study by Stanford University of Business School found out that black men earned at most 79% of what white women earned in similar careers. The study also finds out that men have as much as eight times the chances, than women, of advancing career wise (Federal Glass Ceiling Commission 1995). This led to the Glass Ceiling Phenomenon being officially recognized by the United States government in 1991 and The Federal Glass Ceiling Commission being formed to among other things evaluate the extent at which this phenomenon affects women as well as minority men career progress. The commission was also asked to identify means of countering this situation so as to provide equal and fair opportunities for all (MacRae 2005).

Surprisingly, studies related to the glass ceiling phenomena reveal startling statistics. Despite the fact that women as tend to have a lower rate of career progress than men, they have equal if not better qualifications than men. A study by the U.S. Census Bureau (2005) states that the number of women who have enrolled for under graduate degree program in the United States outweighs the number of men in undergraduate degrees by 7 percentage points. The same study reveals that women also outdo men in enrollment on master degree programs and despite the fact that women enrollment rates is below fifty percentage at the doctorate level, the rate has been rising steadily. This assertion is supported a report by the United Nations on education in 85 of its member nation’s which shows that the number of women outstrips men in the attainment of graduate and post graduates education.

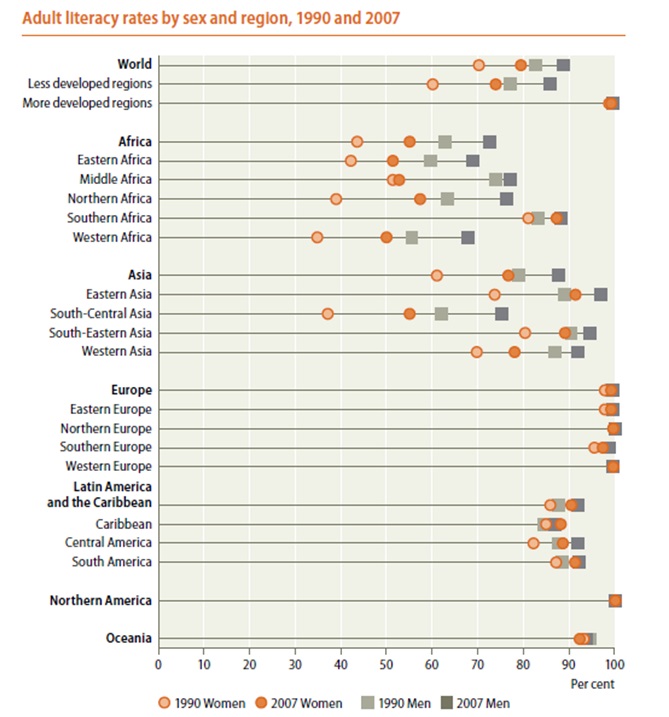

56% of Master’s graduates are women while the number of women graduates has outstripped men by 2 percentage points globally (UNESCO 2010). These findings are further supported by The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat’s 2010 study which reveals that globally, the literacy gap between men and women has narrowed significantly, by three percent between 1990 and 2007 (United Nations 2010). This implies that more women are gaining increased access to education at all levels. This includes the hospitality and service related courses, in which women enrollment has increased by 41 % (U.S. Census Bureau 2005). This is reflected in table 3.1 below. Yet still women lag behind in career advancement as compared to men. This implies that there are unseen barriers that hinder their upward mobility in the corporate world (Finance & Economics 2006).

Gender social roles and the division of labor

Studies conducted reveals that men and women progress differently career wise. There is overwhelming evidence that women progress at a slower pace than men. Furthermore, these studies reveal that there are certain career levels beyond which only fewer women advance. This is regardless of their previous career job experience, education background, professional and qualifications (Kirchmeyer 1998; Russell 2002) As such women face a number of challenges that determine their career progress. These challenges are induced by the social roles that women play at home and in the society (Strober 1982). The social roles theory stipulates that there is division of labour between men and women in the society, which comes out as a result of gender stereotyping. Men are traditionally seen as providers for their families and therefore have to earn a livelihood through gainful employment (Eagly 1987).

As such employment is traditionally seen as the preserve for men. Eagly, Wood and Diekman (2000) argue that this has basic implications on male social roles. Men assume more leadership positions at home and in the society, due to the fact that gainful employment economically empowers men over women. The success of men is measured by how higher they climb in the cooperate ladder. Women on the other hand are the child bearers, and thus take the primary responsibility of taking care of their families. As such they have eventually evolved as home makers and family care givers. This role means they have to stay at home most of the time. These perceptions on gender roles are transferred parents to their children and thus passed from one generation to another (Eagly & Karau 1991).

Due to the social roles that each gender plays, men and women develop different social behaviors to conform to social expectations. Men have an inclination to be assertive, controlling, and independent. They also develop aggressiveness. These traits are more preferable in business leadership. Contrastingly, women, due to their care giving role develop unselfishness, motherliness and friendliness. As such they are prone to accommodate others (Eagly 1997). Furthermore, due to these socially induced behaviors, women tend to take supportive roles to men at home and by extension in the society. Suffice to say that these behaviors are prescriptive and not descriptive. This implies that either men or women can violate these social roles. However, such violation comes with social implications as such men or women who violate them seem more unsavory. To fit into the social context, men as well as women have to conform into these roles (Rudman 1998). This effect is transferred to the work place (Eagly & Johnson 1990).

Influence of social roles on personality formation and career

The social roles that men and women play predispose them to adopt certain behaviors. This behavior becomes embedded and over time they have a bearing on their particular personality types. There is overwhelming evidence that suggest that due to the subsidiary role that women play, they tend to feel excluded from major decision making in the society and as such withdraw themselves from pursuit of personal goals, which includes personal advancement as well as career pursuits. Women thus seek other avenues where they find full meaning of their worth. This is in the family. They do this with the intention of conforming into their prescribed social role as family care givers, to retaining their social identity. Because most of family care giving roles revolves around making friendships, women thus develop personality types that inhabit selflessness and relationship formation. As such women in efforts to retain their social identify develop personality types exposes them to play more communal work than self gratification and personal advancement roles. Women have thus fashioned for themselves a domestic identity (Aydin, Graupmann, Fischer, Frey & Fischer 2011).

John Holland developed a framework for describing the different personality types that determine career progress. These personality types are: realistic, investigative, artistic, social and enterprising or conventional. Holland further stipulates that each of these personality types are determined by the social roles that people play. As such men and women, for playing different social roles assume, develop contrasting personalities among the ones he gave. Because women play more domestic oriented social roles, they thus by default develop to be artistic, social and conventional. These three personalities, Holland concludes channel women into more female related occupations (Stitt-Gohdes 1997). Seymour (1999) adds that societies shape men and women to adopt different personalities, and the result is notable social inequalities between men and women (Acker 2006). Furthermore, many societies have viewed occupations as either fit for either male or females. Such inequalities are further manifested in the work place where men dominate women. This corroborates the assumption that the roles that men and women play in the society leads to personality formation. The type of personality thus has a bearing on the chances of development and advancement of personal career goals.

In contrast, males are brought up by the society to develop competency and accomplishment because they grow up learning how to compete, and be assertive and directive (Seymour 1999). This has implications for men in the workplace where they behavior is transferred. Many cultures have ways of letting men develop assertiveness and defectiveness (Green and Cassell 1996). and as such are placed in a better position to be decision makers than women. On the other hand because females grow up learning how to make relationship and also to accommodate others, they invariably become subject to male directive behavior. This inevitably leads them to lag behind men in terms of career progress. As such the socially induced personify types that women acquire tend to make them more susceptible to career retrogressiveness (McIlwee & Robinson 1992; Oakley 2000).

Personal career strategies

In relation to career progress and the glass ceiling phenomena, the relationship between social roles and career strategy is found to have major implications on the pace at which women advance in the work place. As explained by Holland, social roles do predispose women to certain personalities namely artist, social and conventional (Stitt-Gohdes 1997). Such personalities are supported by certain behaviors that are also induced by the social roles that women play. These behaviors include relationship building and care giving, which make women to be more accommodating (Major 1989).

The ability and predisposition to be accommodating is taken as part of career strategy by those women who still hold the traditional view that women are the family caretakers (Evans 1974; Caproni, 2004). Accommodation has a bearing on the chances of women career progress in a number of ways. Women are seen to accommodate careers into their family lives. As such they do not have long term career goals as they do not want their careers to interfere with their family responsibilities (Dupuis 2007). It is worth noting that women do not want to make any career commitment due to family obligations. They see a career as a means to immediate gratification and not for any long term bearing on their lives.

Those women who are courageous enough only make commitment to careers if that commitment does not interfere with their family lives and their husbands career paths (Simpson and Lewis 2007). Furthermore women have developed creative ways of accommodation careers into their family lives. These accommodating strategies include taking part time jobs or jobs that do not involve too much as not to put their family responsibility in jeopardy (Bailyn 1974). Concurrently at the work place, accommodation plays a role in determinate way in which women progress career wise. Women tend to accommodate the views of their male counterparts and as have a tendency not to defend their views. In this case they are seen as backbenchers who are not able to make and defend their firm corporate decisions (Brooks 1970). This affects their chances of career growth. Thus the situation is more than glass ceiling as women care progress strategies are retrogressive (The Federal Glass Ceiling Commission 1995).

Corporate hiring strategies and attitudes

The manifestations of the glass ceiling phenomenon described above, especially on personal career strategy is within women’s sphere of influence. However, there are some dimensions of the glass ceiling that are outside the women spheres of influence. This out of reach influences are mostly seen in the corporate hiring strategies. Most corporate human resource mangers are accused of having notional bias agaist women when describing the ideal career candidate (Judge and Locke 1993). What comes to mind when the phrase ideal career candidate is mentioned to most of these managers is a white male. As such their subconscious mind discriminates women when it comes to hiring of prospective candidate (Tienari, Quack and Theobald 2002).

A study by The Federal Glass Ceiling Commission found out that women went through more number of interviews during the recruitment exercise, an exercise that asserts the notion that most of hiring managers see women as not as fit as men to occupy certain position in their firms (White 1995 as quoted in The federal Glass Commission). Furthermore, a number of the top five hundred companies were found to have a human resource policy that was ration based, giving a lesser ration to women say, 60 : 40 (men : women) (The Federal Galls Ceiling Commission 1995). Van Nostrand (1993) says that some of the corporate managers make their hiring decisions based on their perception as well an opinion on gender roles that both men and women play while Heilman (1983) terms this as sex based hiring judgment. Therefore, human resource practitioners with such notions about gender roles will tend to discriminate women during the hiring and promotion exercises.

Counter strategies

In light of the findings that there are barriers that hinder the growth and developments of women career wise, several strategies have been developed (Melamed 1995; Broadbridge and Hearn 2008).). There are a number of paradigms that have been suggested to overcome especially the barrier posed by gender discriminating hiring practices (Brownell 1994). One of the most effective paradigms combines business ethics and equality. The paradigm suggested by Thomas and Ely is referred to as the Fairness and Golden Rule Paradigm which stipulates equal and fair opportunities for all regardless of gender, race and other form of stereotyping. This paradigm sees both men and women as equal for hiring or promotion and as such should be hired on merit (Burke & Vinnicombe 2006; Powell and Butterfield 1994). Furthermore there needs to be a paradigm shift by both corporate as well as business manager regarding the role of women the corporate world (Tharenou 2005; Federal glass ceiling commission 1995).

Rudman (1998) explains that due to the varying social roles that men and women play, they develop certain type of behaviors which help form social identities. However, this identity is not descriptive but prescriptive as it all depends on how both boys and girls are brought up. Rudman (1998) and Malon and Cassell (1999) add that within some families, girls take leadership roles especially when they are left home to take care of their siblings. With time such girls develop aggressiveness, similar to the type of aggression developed by boys. This means that gender identities are not static and can thus be changed depending on how children are raised. Thus it is the responsibility of parents to raise girls and boys equally and expose them both to activities that will lead to acquisition of aggressiveness as well as directive behaviors. When girl develop such traits they will be able stand out in the workplace as capable managers. Such notion will also help to change the organizational cultures in many firms where women are seen as secondary to men. An overhaul of such corporate cultures means that organization will be able to mange labor force diversity (Kirton and Greene 2000) and gender sensitive equality is going to be attained (Federal Glass Ceiling Commission 1995).

Conclusion

Three main reason tend to obstruct the developed of careers by women. These reasons are the individual personalities that are induced by the social roles that women play. Social roles has a bearing on the overall personality formation in that their roles are family care taker lead them to adopt relationship and accommodative behaviors, which invariably mean that they lack aggressiveness which is a vital quality in career advancement. As such they learn to be selfless. This means that when these attitudes are transferred to the work place puts them at disadvantaged positions. Their tendency to be accommodative also affects their career growth strategies.

Women tend to accommodate careers into their busy family schedules. This leaves them with limited opportunities for career growth. Furthermore, women are also subject of corporate hiring strategies. Some corporate managers seem to have certain notions regarding the abilities of women in professional field. This means that such managers have a psychological bias towards women. In spite of these challenges women have taken the responsibility of advancing their opportunities through the pursuit of relevant educational achievement. However, these three reasons mentioned here in tend to play a more powerful role in obstructing the advancement of women in the professional world.

Reference List

Acker, J. 2006. Inequality regimes: Gender, class and race in organizations. Gender And Society, 20(4), 441-464.

Aydin, N., Graupmann, V., Fischer, J., Frey, D., and Fischer, P. 2011. My role is my castle–The appeal of family roles after experiencing social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 981-986. Web.

Bailyn, L. 1974. Accommodation as a Career Strategy: Implications for the Realm of Work Sloan School of Management, M.I.T. Web.

Barrows, C. W., & Bosselman, R.H. (1999). Hospitality Management Education. New York: The Haworth Hospitality Press.

BBC. 2007. No women chiefs’ in 38% of firms. Web.

Becker, G.S. 1985. Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. Journal of Economic literature, 3, 33-58.

Becker, G.S. 1975. Human capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press Bierema, L.L. (1998). Women’s career advancement across the lifespan: insights, and strategies for women, organizations and adult educators. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, (80). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bily, S., & Manoochehri, G., 1995. Breaking the Glass Ceiling. American Business Review. June. 33-40.

Broadbridge, A., & Hearn, J. 2008. Gender and Management: New Directions in Research and Continuing Patterns in Practice. British Journal of Management, 19(1), 38-49.

Brooks, K 1970. Relative priorities in the job-family relationship: Unpublished masters thesis, Sloan School of Management.

Brownell. J. 1994. Personality and career development: A study of gender differences. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly. 35(2), 36-45.

Burke, R., & Vinnicombe, S. 2006. Advancing women’s careers. Career Development International Vol. 10 No. 3, 2005 pp. 165-167

Caproni, P. 2004. Work/life balance: You can’t get there from here. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 40(2), 208 -218.

Choi, J., Woods, R., Murrmann, S. 2000. International labor markets and the migration of labor forces as an alternative solution for labor shortages in the hospitality industry”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 12 Iss: 1, pp.61 – 67

Dupuis, A. 2007. Work -life balance: Rhetoric or Reality. In M. Waring & C. Fouche (Eds.), Managing Mayhem (pp. 70-85). Wellington: Dunmore Publishing.

DuBrin, A. J. 1994. Sex differences in the use and effectiveness of Tactics of impression management. Psychological Reports, 74(2), 531–544.

Eagly, A. 1987. Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Eagly, A. 1997. Sex differences in social behavior: Comparing social role theory and evolutionary psychology. American Psychologist, 50, 1380-1383.

Eagly, A. and Johnson, B. 1990. Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 233-256.

Eagly, A. and Karau, S. 1991. Gender and the emergence of leaders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 685-710.

Evans P. 1974. The price of success: Accommodation to confronting needs in managerial careers. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Sloan School of Management.

Federal Glass Ceiling Commission. 1995. Good for business: making good use of the nations human capital: environmental scan. A fact finding report

Finance and Economics. 2006. A guide to womenomics. Web.

Gordon, J., & Whelan-Berry, K. 2005. Women at midlife: changes, challenges and contributions. In R. Burke (Ed.), Supporting Women’s Career Advancement, Challenges and Opportunities (pp. 125-147). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Green, E., and Cassell, C. 1996. Women Managers, Gendered Cultural Processes and Organizational Change. Gender, Work and Organisation, 3(3), 168 -178.

Heilman, M. 1983. Sex bias in work settings: The lack of fit model. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, vol. 5 (pp. 269-298). Greenwich, CT.: JAI Press.

Hymowitz, C. & Schellhardt, T.D. (1986), The glass ceiling: why women can’t seem to break the invisible barriers that blocks them from the top jobs. The Wall Street Journal –Eastern Edition, March 24th.

IFC. 2009. Promoting development by expanding job opportunities for women. Web.

ILO 2003. Breaking through the glass ceiling: Women in management. Web.

IRS. 2007. Hotel Industry Overview – August 2007 – History of Industry. Web.

Jones, B. 2011. Best Myers-Briggs Type. Web.

Judge, T. and Locke, E. 1993. Effects of dysfunctional thought processes on subjective well-being and Job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78: 475-490.

King, C.A. 1995. Viewpoint: what is hospitality? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 14:3/4, 219-234.

Kirchmeyer, C. 1998. Determinants of managerial career success: Evidence and explanation of male/female differences. Journal of Management, 24: 673-692.

Kirton, G., and Greene, AM. 2000. The dynamics of managing diversity -A critical Approach. London: Elsevier.

Knutson, B.J. & Schmidgall, R.S. (1999), Dimensions of the glass ceiling in the Hospitality industry. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, December, 64-75.

Loutfi, M.F. (2001), Women, gender and work. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Malon, M., and Cassell, C. 1999. What do women want? The perceived development needs of women managers. The Journal of Management Development. 18 (2), 137-152

Major, B. 1989. Gender differences in comparisons and entitlement: Implications for comparable worth. Journal of Social Issues, 45: 99-115.

Martin, J., & Meyerson, D. 1998. Women and power: Conformity, resistance, and disorganized coaction. In R. M. Kramer & M. A. Neale (Eds.), Power and influence in organizations (pp. 311–348).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McIlwee, J., & Robinson, J. 1992. Women in engineering: Gender, power, and workplace culture. Albany: State University of New York.

Melamed, T. 1995. Barriers to Women’s career success: human capital, career choices, structural determinants, or simply sex discrimination. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 44(4). 295-314

Miller B. n.d. History of the Hospitality Industry. University of Delaware. Web.

Oakley, J. G. 2000. Gender-based barriers to senior management positions: Understanding the scarcity of female CEOs. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(4), 321-334

Powell, G., & Butterfield, D. 1994. Investigating the ‘’glass ceiling’’ phenomenon: an empirical study Of actual promotions to top management. The Academy of Management Journal, 37(1): 68-86.

Rudman, L. 1998. Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 629-645.

Russell, D. 2002. In Search of Underlying Dimensions: The use (and abuse) of factor analysis in personality and social psychology bulletin. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 28(12).

Seymour, E. 1999. The role of socialization in shaping the career-related choices of undergraduate women in science, mathematics, and engineering majors. The Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 869(1):118-126.

Simpson, R., and Lewis, P. 2007. Voice, Visibility and the Gendering of Organizations. Hampshire New York: Palgrave McMillan.

Strober, M. 1982. The MBA: Same passport to success for women and men? In P. Wallace (Ed.), Women in the workplace (pp. 25–55). Boston: Auburn House.

Stitt-Gohdes,W. 1997. Career development. Columbus, Ohio: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career and Vocational Education.

Tharenou, P. 2005. Women’s Advancement in Management : What is known and future areas to address. In J. Burke & M. Mattis (Eds.), Supporting Women’s Career Advancement. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Tienari, J., Quack, S., and Theobald, H. 2002. Organizational reforms, ‘Ideal Workers’ And Gender Orders: A Cross Societal Comparison. Organizational Studies, 23(2), 249-279.

UNESCO. 2010. Global Education Digest 2010 : Comparing Education Statistics Across the World. Web.

United Nations. 2010. The World’s Women 2010: Trends and Statistics. Web.

US Bureau of Statistics. 1995. Monthly labor review. Web.

US department of Labor, 2010. Quick Stats on Women Workers, 2009. Web.

Vargas, M., and Aguilar, L. 2002. Tourism. Web.

White, J. 1995. A few good women. In The Glass Federal Glass Ceiling Commission (ed).

Zhong, Y. 2006. Factors affecting women’s career advancement in the hospitality industry: perceptions of students, educators, and Industry recruiters. Web.