The landmark multilateral agreement at the Bali conference in Indonesia under the umbrella of the WTO remains a major achievement of the Doha Declaration. The ministers had agreed to adopt about 50 decisions on different issues such as agriculture, investment measures, textile and clothing, technical red tapes to trade, and subsidies.

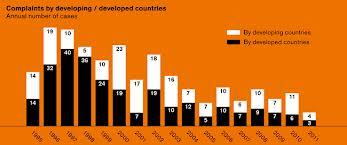

Even as some pundits hold that Doha had finally delivered one of its agendas, the nature of market operation characterized with big and small economies remains unclear (“The World Trade Organization: Doha delivers” n.pag).

The deal that intends to reduce bureaucratic procedures and red tapes in the shipment of products around the world in order to boost global trade has received castigation from other quarters; there are claims that the agreement will obstruct nations from setting their own urgent programs concerning food security, rights of workers, and environmental protection. To maintain balance in the system, all nation-states have a duty to play by the same regulations stipulated in the international agreement.

In keeping the Doha agenda attractive and simple as possible, the Director-General, Roberto Carvalho de Azevedo, intended to bring on board all the 159 member nations of the WTO. Tracing the path of Doha’s functions reveals an international organization that is fighting to bring sanity in the global trade, which has been engulfed with strong suspicions from different quarters. Economic ideas, strengths, and influences are some of the major impediment issues that the WTO has faced in its attempt to pass global trade legislations.

For example, nations like Cuba, India, Venezuela, and China believe that the international body is majorly legislating policies that protect and enforce America’s trading rights. On the other hand, the agreement reached the Bali Island conference was not only one of its kind in the 20-years history of the WTO but also intended to simplify customs procedures in order to instill transparency by easing trade barriers.

Clearly, market liberalization gives all nation-states equal bargaining power in the international front if the developed economies comply with the same trade rules to the letter (“Trade facilitation agreement” par. 4).

The plan to facilitate trade by removing existing restrictions, on the one hand, is beneficial as its targets to cut the cost of global trade by over 10% in order to raise the annual global output by more than $400 billion. Conversely, most poor nations will find it too expensive to meet the cost of the required capacity upgrades, thereby forcing the developed economies to offer assistance to facilitate the implementation of the agreement.

The Doha-lite Bali package fails to resolve some petty issues that can easily impoverish poorer nations. The move needs to protect farmers from challenges of market liberalization to make skeptical nations like India and China to support the multilateral process. The skeptical nations ought to understand that under multilateral relations, member states have to practice a give-and-take affair.

Therefore, it is ‘rude’ for a country to reject an entire agreement if it partially meets its desires. In essence, trade facilitation helps in eliminating bottlenecks, cutting trading costs, boosting the flow of goods and services, and reaping more benefits from transnational trade (“Trade facilitation agreement” par. 6). The use of advance rulings, streamlined procedures, harmonized and simplified documents, and accessibility of trade-related data in the WTO’s negotiation, outrightly, address specific hurdles in the cross-border trade.

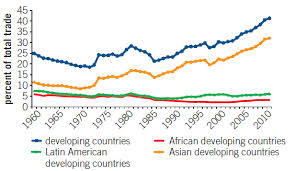

The trade facilitation indicators reduce transaction cost that has been notoriously high, particularly in poor nations. The Doha-lite Bali package presents additional benefits to Least Developed Country members. For example, numerical data from Peterson Institute study predicts a real income gain of 2.6% for LDCs and 1.0% for the developed nations.

Trade integration has numerous benefits compared to the challenges that skeptic nations raise. The WTO provides the best avenue for ‘plurilateral’ and multilateral deals. Food security in the entire globe needs a collective approach, which is only possible if the Bali package is implemented properly.

The Bali deal instructs developed nations to assist the poorer WTO members in enacting the agreement in order to reduce quota limits and tariffs on imports (“The World Trade Organization: Doha delivers” n.pag). Even though the deal is beneficial to poorer nations and developed nations as well, the sustainability of the system is fundamental to the realization of its goals.

According to Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Cuba, the agreement escalates the economic difference that exists between developed and developing countries. However, with clear risk management systems, customs processing, a sole window document submissions, and trusted trader programs, the WTO is closer to ending food insecurity, investment issues, and discrimination in trade embargoes (“Round-the-clock consultations” par. 7).

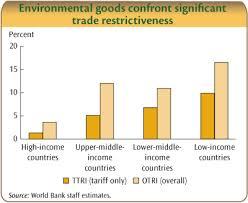

Even though the package fails to address issues of trade barriers like quotas and tariffs, it is imperative to note that introducing several regulations in a liberal economy is likely to face rejection from most members; the process should not be drastic, to avoid refutation from member states. Nevertheless, it is clear that a reduction in trade barriers creates employment for both the low and high-skilled workforce in all countries. Undoubtedly, the WTO has created an opening for the development of the world’s economy.

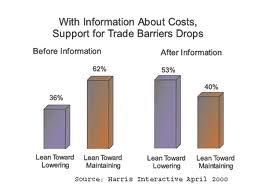

The tables, charts, and graphs below elaborate the effects of market liberalization as put forward by the WTO.

Works Cited

Round-the-clock consultations produce Bali Package. N.p., 2013. Web.

“The World Trade Organization: Doha delivers.” The Economist [London] 2013: n. pag. The Economist. Web.

Trade facilitation agreement would add billions to global economy. N.p., 2013. Web.