This paper reviews the existing literature in support of the research study. The literature reviewed discussed the barriers and success strategies for African American Women to obtain higher education. Also, a discussion of the Critical Race, Social Learning, and Feminist theories was included that formed the understanding of African American female educational development. Despite the growing awareness of the problem in the literature, little attention has been given to studies of overcoming barriers and obstacles to higher education for African American women (Baber, 2012; Charleston, 2012; Felder & Barker, 2013).

The problems of African American students in the sphere of education were traditionally discussed without direct reference to community colleges as a specific educational institution type. In their research, Felder and Barker (2013) studied the African American students’ experiences only in elite and Southern institutions, such as the University of California and Southern States University. There are gaps in the scholarly discussion of the African American students’ barriers, obstacles, and challenges in receiving the Associate degree.

According to the literature, African American women routinely experience problems and face challenges in clearing a higher education path. The research literature has identified common barriers hindering African American women’s experiences in higher education to examine and identify what barriers can prevent them from entering college and completing their Associate degree. Some of the identified barriers can be grouped into the following categories: stereotypes, racial and gender bias, lack of networking opportunities, and lack of organizational commitment.

The research will add to the knowledge base to better understand the educational challenges and success factors of African American women and how public administrators can make changes in Prince George’s Community College (PGCC) in addition to the effectively implemented programs for the promotion of diversity, such as Women of Wisdom and Vocational Support Services (Prince George’s Community College, 2015b).

The paper will also look at specialized programs at the college that can have a significant impact on making the educational experience of African American women more positive and help them reach their educational goals.

The Role of Public Administration and Higher Education

In the context of higher education, public administration guarantees the implementation and effective utilization of a range of policies and programs that are oriented to addressing the issue of receiving a higher education by minority groups. The ideas of diversity and inclusion are reflected in the policies adopted by post-secondary educational institutions in the United States, and this approach allows for eliminating the negative impact of political, economic, and social factors, including issues of ethnicity, race, gender, and socioeconomic status, on individuals’ access to higher education.

From this perspective, public administrators are concentrated on researching the needs of certain groups of people to propose solutions to problems or barriers with the help of public resources and appropriate policies or initiatives (Fenwick & McMillan, 2014).

Public administration within the context of higher education allows schools to provide services to specific underserved individuals attending the school. Public administration is important when working at community colleges because it can help students at these colleges deal with specific issues. For example, public administration could help individuals at the college who have children deal with simultaneously being students and parents.

Similarly, it is also possible for public administration programs to help students find jobs in a field that could help them advance their careers instead of simply having them find jobs that allow them to pay their bills while in school (Fenwick & McMillan, 2014). Universities need to address these issues when working with disadvantaged students, specifically because it ensures that they can develop the life skills necessary after college. It is insufficient for students to attend college without gaining skills that are useful outside of college. Accordingly, it is valuable for them to have access to programs that give them tools for success outside of their university experience.

At the current stage, efforts of public administrators in addressing the issue of receiving a higher education by minority groups are viewed as successful. However, there are still areas for improvement because of the impact of political, economic, and social factors that include the focus on students’ ethnicity, race, gender, and status as barriers to their education. Ringeling (2015) also notes that public administration as a field of practice concerns the preparation of public administrators as providers of public services, and it is also related to the development and implementation of certain policies and strategies to promote the change in public agencies, institutions, and society.

Thus, in the field of higher education in the United States, the activities of public administrators are directed toward improving the availability of higher education for African Americans with the focus on women’s opportunities and experiences regarding obtaining an academic degree.

Researchers pay much attention to discussing the role of public administration and associated services in the context of higher education and individuals’ access to it. According to Shand and Howell (2015), the role of public administration in the sphere of higher education is important because post-secondary educational institutions are oriented to covering the needs of people regarding their education and further career development.

Public administrators can regulate and manage all issues and obstacles faced by individuals on their paths to higher education. Furthermore, many cases associated with the sphere of higher education can be resolved only involving public administrators as effective managers and even policymakers, as it is in the case of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) initiatives (Fenwick & McMillan, 2014; Strayhorn, 2015).

Therefore, the role of public administration in regulating activities of higher educational institutions is considerable. PGCC can be viewed as a model because of its effective practices, including the development of the Women of Wisdom program for promoting female students and the Vocational Support Services program for additional mentoring and support for students (Prince George’s Community College, 2015b).

Public administrators are focused on formulating questions to resolve, researching issues and related facts, and proposing effective strategies to address the identified problems. According to Shand and Howell (2015), it is important to discuss the role of public administration in relation to higher education from the perspective of public administrators’ effectiveness in resolving all issues that can be observed in modern educational institutions in the United States.

One of the public strategies aimed at attracting African American women to US colleges and universities was the effort of the Obama Administration to involve African Americans in historically black colleges, community colleges, and predominantly white institutions for receiving the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) degree (Alexander & Hermann, 2016; Jackson, 2013). The principle of STEM education was formulated by the Obama Administration as a priority for opening these educational fields for minorities, including women (Alexander & Hermann, 2016). The reason was that women of color were previously underrepresented at faculties associated with obtaining a degree in technologies or engineering.

The role of public administration in guaranteeing higher education for African American women is also in developing programs and initiatives to support low-income female students, provide them with scholarships, and organize funds to address the needs of minorities (Fenwick & McMillan, 2014). According to Ringeling (2015), efforts of public administrators in the United States regarding the attraction of African American women to higher educational institutions led to increasing the number of women of color in historically black colleges, community colleges, and predominantly white institutions.

However, it is important to note that these figures still need to be monitored because many minority women continue to experience barriers to higher education, and they are often deprived of opportunities to obtain an academic degree. As a result, the accentuation of positive trends in changes in enrolment rates can reflect the real situation inappropriately, and research indicates that many African American women still continue to report barriers and different types of challenges (Harris, 2017; Iloh & Toldson, 2013). Therefore, more activities of public administrators should be oriented to addressing the problem of the underrepresentation of black female students in post-secondary educational institutions.

However, even though African American women are beginning to matriculate at these institutions, it is still important to monitor and track these figures. There are several reasons why this is the case. First, African American women still face substantial discrimination with respect to jobs and social status after graduating. Thus, institutions need to monitor these statistics to ensure that African American women can meet their needs after they graduate. Furthermore, it is possible that African American women would experience discrimination or lack opportunities at university. Accordingly, it is important to monitor their experiences while at the university instead of simply accepting the matriculation numbers to show that the problem is no longer existent.

Historical Overview of African American Women Obtaining Higher Education

The problem of the disproportionate college enrollment in relation to African American women can be discussed as having historical background. African American women’s opportunities to obtain higher education were always limited in the United States. The situation began to slightly change only in the 1960s after the decision declared in relation to the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954).

Following this decision, racial segregation in the US educational institutions became viewed as unconstitutional (Garibaldi, 2014). However, despite the increased higher education enrollment for minorities, African American women were still underrepresented in colleges and universities in comparison to white females (Garibaldi, 2014; Iloh & Toldson, 2013). In the 1960s and 1970s, affirmative action policies allowed for improving the situation for women in historically black institutions. Still, overall rates of African American women with academic degrees remained to be low.

Although rates of graduating from high school for African American women increased significantly in the 1970s and 1980s, their enrollment in higher educational institutions was still limited. In his descriptive quantitative study, Garibaldi (2014) examined the situation in relation to African Americans and stated that the percentage of women of color in colleges and universities of the United States still remained to be low in comparison to the number of white students.

Thus, “59,100 Black students graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1976 compared with 60,700 in 1981—an increase of only 1,600 Black graduates between those two years” was observed, which means the increase is only about 2.5% (Garibaldi, 2014, p. 372).

However, in the 1970s, the number of women of color with a degree was higher than the number of African American males who received academic degrees in educational institutions because “Black males received 7,900 fewer degrees than Black females in 1976, and 11,700 fewer in 1981” (Garibaldi, 2014, p. 372). These statistics suggest that there need to be policies that are specifically geared towards providing African American women with opportunities when they attend colleges, as opposed to African Americans generally.

The substantial disparity in achievements for African American women suggests possible disparities between access to education and obtaining a degree. Some of the potential reasons for this include teen or early pregnancy amount African American women. Women who have children have difficulties with succeeding in school. Accordingly, it may be important for these universities also to provide resources so that these women can also succeed and demonstrate higher results. Alternatively, sexism, coupled with minority status, may represent a significant hurdle for women who are minorities.

Historically, the low degree completion for African American females was associated with a range of factors, including social and economic ones, as well as these women’s choices of vocational training. As a result, during the 1980s and 1990s, most African American women received professional training and were not involved in studying engineering, technologies, and science. Thus, in 1982, “college enrollment after high school was 40 percent for Blacks compared with 53 percent for White students” (Iloh & Toldson, 2013, p. 205). The key focus was on nursing, education, and human resource management (Bartman, 2015). Felder and Barker (2013) analyzed the data for the 1990s and 2000s, and they stated that the involvement of African American women in receiving doctoral degrees was only about 10%.

Furthermore, traditionally the limited number of African Americans studied in higher educational institutions. The limited number of women of color was the part of the faculty to support minorities as less than 20% of African American women could receive doctoral degrees compared to other women and males graduating from educational institutions (Felder & Barker, 2013; Garibaldi, 2014).

Many studies have examined the situation in obtaining a higher education by African American women. McCoy (2014) noted that, although statistics demonstrate that more African American women received academic degrees in comparison to black males during the period of the 1980s, and they were actively enrolled in educational institutions in the 1990s, the situation was positive only with the focus on historically black institutions or community colleges.

The number of African American males who studied in predominantly white institutions or who received masters and doctoral degrees was always higher, accentuating the gender gap and inequality in the sphere of higher education (Iloh & Toldson, 2013; McCoy, 2014). As a result, a historical overview of females’ educational experience indicates that it is possible to speak about certain barriers for African American women on the paths to higher education.

Current Status of African American Women in Higher Education

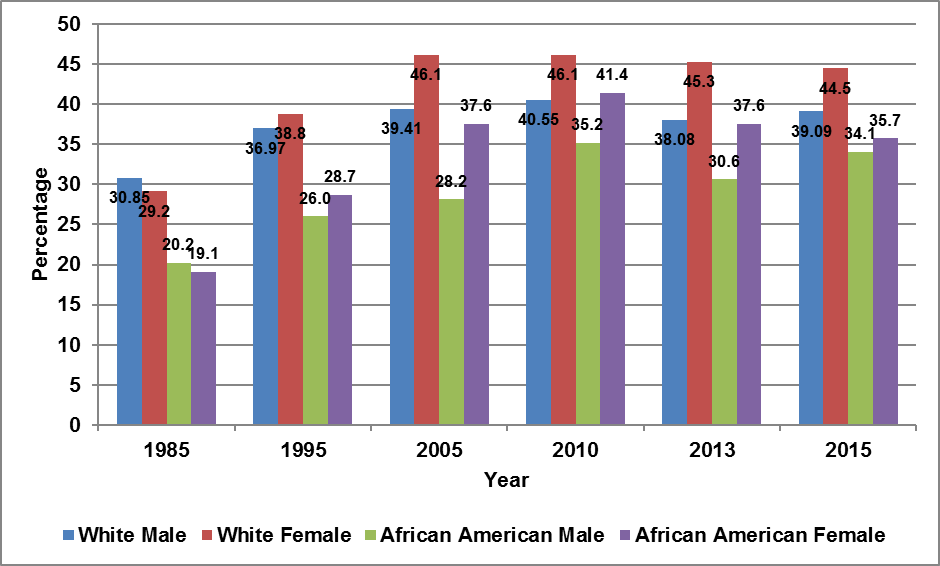

The current status of African American females in higher education is important to be studied in detail in order to conclude on possible changes in women’s access to receiving academic degrees. According to the data collected and analyzed by National Center for Education Statistics (2016), the percentage of African American female students enrolled in post-secondary educational institutions increased from 19.1% in 1985 to 35.7% in 2015.

For African American males, this percentage changed from 20.2% in 1985 to 34.1% in 2015 (Figure 1). It is possible to observe that the number of African American female students studying in colleges is slightly higher than the number of African American male students (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016). However, while comparing the data for African American and white female students, it is important to note that in 2015, 44.5% of white females were enrolled in US colleges in comparison to 35.7% of African American female students (Figure 1).

While discussing the situation regarding the enrollment of women of color in colleges, it is possible to focus on the tendency typical of higher education in the United States: the number of women studying in post-secondary institutions is higher than the number of men. According to Garibaldi (2014), this tendency can be observed since the 1990s. Nevertheless, the number of African American female students who received degrees during the period of 1990-2012 is low while comparing it to the number of white women who received the same degrees (Iloh & Toldson, 2013).

Felder and Barker (2013) noted that, despite the improved access of women of color to higher education, the observed racial disparity does not allow for speaking about removing all barriers for Africa American women to obtaining a degree.

In spite of policies oriented to increasing the enrollment of African American female students in colleges and universities, the graduation rates for women of color are also low because many of them leave institutions without receiving diplomas because of a range of factors and barriers, including the lack of support, family situations, discrimination, and the need for a full-time job (Bartman, 2015). The literature and statistics demonstrate that there is still a gap in the number of African American female students receiving degrees in comparison to white females.

Researchers are also concentrated on the current status of African American female leaders in higher educational institutions. Wallace, Budden, Juban, and Budden (2014) paid attention to the fact that the lack of African American females at faculties of different institutions is one of the reasons for the limited number of black female students in these colleges and universities. A positive tendency can be observed only with reference to historically black institutions and community colleges (Jackson, 2013).

According to Davis and Maldonado (2015), both African American females and males became presidents of or took leadership positions in about 90 historically black institutions, but the percentage of African American female leaders in post-secondary institutions is only about 4-6%. Furthermore, when women of color seek admission to a predominantly white institution, they usually face significant barriers (Wallace et al., 2014).

This tendency is associated with the comparably low number of women of color involved as tutors or professors in predominantly white institutions. From this perspective, the literature accentuates a significant gap in the representation of not only black female students in colleges and universities of the United States but also black female faculty members and leaders.

Lack of Organizational Commitment

The review of the literature on the topic of African American women in higher education indicates that researchers are interested in studying causes and factors that can be associated with black females’ impossibility to graduate from US colleges and universities even if they were successfully enrolled in institutions. According to Bartman (2015), the problem is in the lack of commitment and motivation because of observed barriers and challenges.

Thus, Felder and Barker (2013) stated that many African American females choose to leave institutions before graduating because of facing such problems as discrimination, prejudice, a lack of support, economic problems, and family issues, including marriage and pregnancy. PGCC has implemented the Women of Wisdom program and the Vocational Support Services program in order to address these issues.

Thus, Women of Wisdom is a program that gives minority students, particularly women, mentoring and other opportunities to help them succeed in their studies. In its turn, the Vocational Support Services is oriented to provide additional professional training for minority students, and this initiative helps students be successful after they graduate from the university. Counseling and other career services are also important when students come from disadvantaged backgrounds and do not have the requisite experience to succeed in the job market (Prince George’s Community College, 2015b).

McCoy (2014) noted that many black females are not aware of their opportunities for future career development if they obtain a degree because of being afraid of bias and obstacles. Furthermore, having economic and social barriers, African American women can demonstrate the lack of commitment because of focusing on professions that do not require specific education or on their families. All these factors seem to influence the level of black female students’ commitment to studying in post-secondary institutions.

While focusing on such an important factor as the lack of support from peers and faculty members, researchers claim that African American females can have little motivation to receive an academic degree because they do not experience some assistance during their study (Felder & Barker, 2013). Davis and Maldonado (2015) paid attention to the fact that African American female students need mentors in colleges and universities in order to improve their experience and address possible barriers. Such mentors should be representatives of minorities in order to increase black women’s satisfaction and motivation to receive an academic degree.

Thus, female students can experience certain difficulties during their studies. According to Bartman (2015), “there are some institutions where enrollment of Black women is so low that there is no sense of community for these students on campus and therefore their identity development lacks appropriate cultural references,” and this situation negatively affects “retention and attainment rates and adds to the lack of critical mass of this particular student group” (p. 4-5). As a result, the lack of commitment and interest in the study can lead to absenteeism or low attendance rates of African American female students.

Researchers focus on the idea that the problem is in the lack of comfortable conditions for minority students in US colleges and universities. The culture of predominantly white institutions is oriented to supporting white female and male students. However, in spite of the fact that historically black institutions can promote the development of the black culture and the sense of belonging to a community, there are no effectively implemented policies, strategies, and practices that can be used to attract and retain African American students to guarantee their successful graduation (Felder & Barker, 2013; Jackson, 2013).

A similar situation is observed at community colleges where the number of African American students is high, but the attention paid to their support is not enough (Iloh & Toldson, 2013). All the discussed factors can influence black female students’ experience regarding their study at higher educational institutions and motivation to receive a diploma.

Critical Race Theory

During the recent three decades, Critical Race Theory has been actively used by researchers in order to critically analyze racial relations in different contexts, including the educational one. The theory was formulated by researchers for the legal context in the 1980s-1990s, and Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic formulated its widely applicable premises in 2001 (Ledesma & Calderón, 2015). The key assumption of Critical Race Theory is that it is possible to observe white supremacy and racism in all spheres of the US society (Ledesma & Calderón, 2015; Savas, 2014).

Thus, according to Savas (2014), this theory declares that “racism still exists in our society and is part of our everyday reality but in more subtle, invisible, and insidious ways in contrast to the past” (p. 508). Furthermore, the goal of this theory is to demonstrate the tools available for destroying racist structures in US society. The theory is also aimed at explaining relationships between the idea of race and its representation in different social contexts (Harris, 2017). In the 1990s-2000s, researchers began to apply this theory to analyzing experiences of racial minorities in different environments, including the field of higher education.

Critical Race Theory explains social dynamics in the US society with reference to claims that all power is concentrated in the hands of whites, and, as a result, representatives of racial minorities can experience certain challenges and barriers while obtaining a higher education or seeking a job (Savas, 2014). Theorists state that this tendency is explained with the focus on the history of white privilege associated with the US society (Ledesma & Calderón, 2015; Savas, 2014). Harris (2017) notes that this theory is also effective in discussing and analyzing the phenomenon of racial stereotypes in various social sectors. Therefore, Critical Race Theory is widely referred to in the literature on problems in education associated with representatives of different races.

While applying Critical Race Theory to studying African Americans’ experiences related to obtaining a higher education, it is possible to state that this theoretical model is appropriate to explain cases of racial discrimination in educational institutions, achievements in the field associated with the civil rights legislation, and the idea of racial differentiation that can influence educational experiences of people with different ethnic backgrounds (Ledesma & Calderón, 2015; Savas, 2014).

This theory tends to explain why those African American women who are focused on obtaining a higher education can face specific barriers and determine factors that can contribute to the development of institutional bias (Ledesma & Calderón, 2015). From this perspective, it is important to note that Critical Race Theory can provide an appropriate theoretical framework for the study where participants belong to the minority group in order to clarify the connection between race and students’ experiences in educational institutions.

Social Learning Theory

Social Learning Theory is a widely known psychological theoretical model that was formulated by Albert Bandura in the 1970s. This theory views learning as an interactive process that is highly influenced by social relations and interactions (Kattari, 2015). As a result, observations of people and social models can influence an individual’s beliefs, values, activities, and behaviors. According to researchers, Social Learning Theory is appropriate to discuss not only how people learn and follow certain social models but also how their actions and socialization depend on different settings (Hanna, Crittenden, & Crittenden, 2013; Kattari, 2015). Therefore, the assumptions related to this theory are the following: people’s behaviors depend on their social learning and experiences, and people’s behaviors depend on contexts and expected or desired outcomes.

Researchers accentuate the importance of Social Learning Theory in terms of explaining reciprocal interactions between individuals and environments in a range of spheres, including education as the key area where social learning plays a critical role (Hanna et al., 2013; Kattari, 2015). Thus, this theory proposes many perspectives from which it is possible to explain challenges or barriers faced by African American women in association with their education. From this point, Social Learning Theory explains that individual perceptions of obstacles and problems can depend on previous learning of social models or on their previous experiences (Hanna et al., 2013).

This approach can explain behaviors of tutors and peers who interact with women of color and have certain prejudice, as well as behaviors of African American female students who can expect bias and behave accordingly. Social Learning Theory suggests that all participants involved in communication or interaction in a specific setting choose behavioral patterns depending on their previous social learning, and their visions and behaviors can influence each other.

The key principles and assumptions of Social Learning Theory can be effectively used for clarifying African American women’s experiences in higher educational institutions. Women of color should learn how to interact with representatives of different cultures successfully, and they need to adapt to new social models or to specific models followed by the majority of students in a concrete educational environment (Thomas, Wolters, Horn, & Kennedy, 2014).

According to the principles of Social Learning Theory, if African American females have successfully adapted to a new environment in which white or male students can dominate, they experience fewer obstacles and challenges (Hanna et al., 2013; Kattari, 2015). Furthermore, the visions, values, and beliefs of these women can change depending on the setting in which they interact. Therefore, this theory is selected as a theoretical framework for this study because it can explain how behaviors of African American women and students in colleges can be modified with reference to specific social models and patterns they observe in their daily life.

Feminist Theory

Feminist Theory was developed in the 20th century by a group of researchers as the continuation of discussing the aspects of feminism. This theory is aimed at understanding inequalities that are observed in society in relation to treating females and determining their roles in contrast to males (Collins, 2015; Friedman & Ayres, 2013). Feminist Theory also explains such aspects as discrimination, inequality, oppression, sexual objectification, and stereotyping with the focus on the gender factor (Carastathis, 2014; Friedman & Ayres, 2013). From this point, Feminist Theory is important to discuss and clarify details of gender inequality that can be observed in different social contexts, and this theory is crucial to guarantee a better understanding of specific barriers and challenges associated with women’s positions in society and gender discrimination oriented to them.

It is important to note that Feminist Theory unites a range of feminist theoretical models and movements that differ in their approaches to explaining gender differences, inequality in society, and observed oppression in relation to females. Adherents of feminist theories argue that, in the US society, women are often viewed through the lenses of their sex or gender, and specific biases developed with reference to these views influence the success of females in relation to their education and observed workplace practices (Collins, 2015; Friedman & Ayres, 2013).

Thus, it is possible to state that many researchers choose to discuss experiences of African American women while obtaining a higher education with reference to Feminist Theory because the observed discrimination and structural oppression can be a result of gender-based biases (Carastathis, 2014; Collins, 2015). As a consequence, Feminist Theory is appropriate to explain why African American females in higher educational institutions can be oppressed, offended, abused, and discriminated against without reference to their race.

It is stated in the literature on the problem of African American women’s experiences in post-secondary educational institutions that the role of women in the modern society is reconsidered in the context of feminist movements and other social theories, but the application of feminist theories to studying experiences of women of color is still important because they can face different barriers due to their gender (Carastathis, 2014; Collins, 2015; Friedman & Ayres, 2013).

While identifying barriers that African American women can face in higher educational institutions, it is possible to explain them with the focus on Feminist Theory in addition to the theories related to the aspects of race and social learning (Collins, 2015; Friedman & Ayres, 2013). In addition, the selection of this theory for the theoretical background is important in order to conclude about differences in challenges and barriers that can be faced by African American females in comparison to African American males who usually study in the same institutions.

Challenges Affecting African American Women in Higher Education

Many recent studies are aimed at identifying and analyzing challenges that can affect African American women when they obtain a higher education. For instance, according to Lin (2016), women of color usually face challenges associated with psychological issues, interaction and adaptation to a student community, financial problems, as well as issues related to study and academic performance. Commodore, Freeman, Gasman, and Carter (2016) also support the idea that such challenges are experienced by African American female students at colleges and universities. Psychological issues include stress, anxiety, fear, depression, and fatigue caused by new environments and the lack of support from a family, peers, or the faculty (Hannon, 2016).

The problem is also that women of color often need to overcome stereotypes associated with their learning capacities, among others. These issues are closely associated with such challenges as social isolation, problems with adaptation, stigmatization, the lack of communication with other students, conflicts, and the lack of assistance (Graham, 2016; Patterson-Stephens & Vital, 2017). As a result, more challenges include difficulties with networking and building relationships with professors and other students.

Another category of challenges is related to financial issues. If African American women experience financial constraints, they can be forced to find a job and even drop out of a college or a university. This challenge is typical of women of color who come from families with a low socioeconomic status (Lin, 2016). Moreover, as it is reported in studies, many African American women face challenges while taking extra activities or pursuing their degrees.

Researchers noted that the problem could be not only in the educational background of women of color but also in their vision of their capabilities and self-confidence (Hannon, 2016; West, Donovan, & Daniel, 2016). In addition to these challenges, African American females also experience gender- and race-related stereotyping that can explain the development of the previously discussed problems.

Balancing Career, Family, and Community Commitments

African American female students often need to balance their education with developing a career and family relations, as well as focusing on specific community commitments. According to Lin (2016), the reason is that African American women often choose to continue their education as adults because they are forced by a variety of factors. However, even young African American women who enter colleges need to find a balance in their life because of financial constraints or their marital status (Fountain, 2014; Vaccaro, 2017). As a result, women of color often experience challenges when performing a role of a student in addition to multiple roles of a mother, a wife, a professional, and a community member.

The variety of activities and responsibilities associated with African American female students’ life often leads to their inability to study efficiently because of the lack of time, resources, as well as fatigue and the lack of sleep. Trying to balance the study, employment, family life, and responsibilities of a community member, African American women often choose to pay less attention to their college activities than to other spheres of their life (Hannon, 2016; Mayer, Surtee, & Barnard, 2015).

This situation can lead to potential problems with learning educational material and passing tests and examinations. It is possible to speak about a role conflict that can be observed when an African American woman is expected to perform several social roles. This role conflict potentially results in negative changes associated with a person’s academic achievements (Domingue, 2014; Payne & Suddler, 2014). Still, there are also many examples when women of color demonstrate developed skills in leadership and time management, and they can successfully balance different spheres of their life without affecting their studies (Montgomery, Dodson, & Johnson, 2014). A positive result, in this case, depends on the support available for a woman and her motivation.

Mentoring

Findings of many recent studies support the idea that mentoring is extremely important for African American female students when they pursue their academic degrees because of receiving more chances to ask for advice and find the required information (Montgomery et al., 2014; Sinanan, 2016). In this context, mentorship helps women become more engaged in learning activities, receive support, and develop their academic potential.

As a result of mentoring, female students improve their skills in academic activities and disciplines. Researchers noted that success and improvement in learning were observed when mentors and mentees were of the same race and gender (Commodore et al., 2016; Sinanan, 2016). In this situation, African American women have an opportunity to receive not only academic but also culturally specific and personal advice.

According to the results of many studies, African American women are inclined to rely on their mentors if they are peers or representatives of the faculty because their motivation to demonstrate higher academic achievements increases (Croom, Beatty, Acker, & Butler, 2017; Hannon, 2016; Montgomery et al., 2014). Moreover, mentorship is viewed as an effective practice in order to help young women of color to adapt to specific environments of educational institutions and overcome certain prejudice. The reason is that mentors often perform the roles of advisors, guardians, and supporters at college, and this situation allows African American female students to feel more confident (Domingue, 2014; Graham, 2016; Patterson-Stephens & Vital, 2017).

In addition, according to Commodore et al. (2016) and Sinanan (2016), mentorship demonstrates students as an effective model of behavior in the context of a certain educational institution. Thus, mentors often provide African American female students with information about the settings and specifics of an educational process in this or that college that is not known to individuals outside the campus (Montgomery et al., 2014; Sinanan, 2016). From this point, mentorship is important for the appropriate adaptation of women of color to the environments in which they receive their higher education.

Coping Mechanisms

The realities of obtaining an academic degree often make African American women develop different coping mechanisms that are employed in order to help these persons overcome faced challenges and barriers. Researchers name humor, ignoring, silence, resistance, and aggression among coping mechanisms or strategies that are used by women of color at college or university in order to address experienced oppression, stereotyping, discrimination, and prejudice (Graham, 2016; Payne & Suddler, 2014). Depending on the problem or the type of challenge observed, African American female students choose to demonstrate different types of coping behaviors.

Researchers noted in their studies that stereotyping, financial problems, the necessity of balancing family life and education, the lack of support, and peers’ bias often cause increased stress levels in women of color (Hannon, 2016; Payne & Suddler, 2014). As a result, these women choose to express their emotions openly, or they choose various coping strategies that help them hide their feelings and address the problem. Positive coping techniques are associated with women’s attempts to improve their relationships with other students and the faculty while using humor, jokes, or other similar techniques (Domingue, 2014; Hannon, 2016).

However, many African American women can also demonstrate silence, resistance, or even aggression, and they avoid building strong relations with their peers. These coping mechanisms do not lead to positive outcomes for a person’s psychological state and level of satisfaction.

Another variant of a coping strategy described by researchers is the “blackness.” Thus, African American students, including female ones, can use their race and ethnicity as explanations for their behaviors and reactions (Graham, 2016; Hannon, 2016; Payne & Suddler, 2014). On the one hand, they can accentuate their individualism while opposing themselves to other students or representatives of the faculty. On the other hand, emphasizing their ethnicity, these students try to address experienced racism and stereotyping.

Spirituality

While discussing experiences of young African American female students, researchers also focused on their spirituality as their state of relying on the church and being dedicated to their religion. Furthermore, spirituality in the context of African American women is also viewed as their connection with themselves and others in terms of understanding their identity, developing a sense of coherence, and having connections with the universe (Graham, 2016; Mayer et al., 2015). As it is noted by Mayer et al. (2015), it is extremely important for these women to be aware of their spirituality because African American women’s spiritual practices help them cope with psychological distress and other challenges.

Researchers also found with reference to their studies that African American female students were inclined to apply not only traditional psychological coping mechanisms and strategies but also practices associated with spiritual coping (Graham, 2016; Hannon, 2016; Mayer et al., 2015). It is important for African American women to feel like part of a family, a community, and their church. From this point, spirituality is associated in many African American females with their social and cultural identity. Researchers stated that these women choose to rely on such support groups as their relatives, friends, community members, and their church (Fountain, 2014; Graham, 2016; Hannon, 2016).

Therefore, spiritual coping is also typical of situations when it is necessary to overcome challenges and barriers observed in academic settings. Other investigators also focused on the idea that African American women usually rely on their Afrocentric spirituality as the component of their cultural and ethnic identity (Graham, 2016). As a result, this feeling of belonging helps these women to find their place in the world and adapt to different situations.

Sexism and Racism in Higher Education

The literature on African American women pursuing academic degrees indicates that, in spite of numerous anti-discrimination policies implemented in post-secondary educational institutions, these women still experience sexism and racism. According to Stevens-Watkins, Perry, Pullen, Jewell, and Oser (2014), it is possible to speak about the phenomenon of “double jeopardy” faced by these women that can “explain the effect of racism and sexism experienced by African-American women” (p. 561).

Thus, sexism is realized through gender-based stereotypes, and women can be viewed by male students and the faculty as less concentrated on study than their male peers, as having less developed leadership skills, or as having less motivation to obtain higher education (Lin, 2016; Stevens-Watkins et al., 2014). Moreover, the problem is that African American women can be strongly associated with their families and communities because of a stereotype regarding a typical African American woman (West et al., 2016). The problem is that this stereotype is not related to the education, academic achievements, or professional development of an African American woman.

In addition, it is also possible to focus on cases of sexual objectification in relation to women of color because of the spread of certain stereotypes. According to Domingue (2014), African American women can also experience challenges associated with presenting themselves because they do not want to be regarded only as women instead of being discussed as students or researchers. Thus, the literature on this topic provides a lot of evidence to state that young African American women can face many challenges and barriers while focusing on their higher education because of certain stereotypes that exist regarding the role of a woman, and an African American woman in particular, in the US society (Montgomery et al., 2014; Vaccaro, 2017).

Researchers also paid attention to the problem that, in addition to sexism, African American women in educational institutions can suffer from examples of racism that can be presented as microaggressions and prejudice, among other forms that are associated with accentuating one racial group’s superiority over another group (Commodore et al., 2016; Stevens-Watkins et al., 2014). These microaggressions are typical of personal relationships when African American women are affected by jokes or provocative messages, for instance, and professional relationships when institutional policies reflect some discrimination or bias regarding African Americans.

According to Vaccaro (2017), the problem is that representatives of an academic community can spread and share deficit-based stereotypes based on race and ethnicity. As a result, African American women can be perceived as having less capacity to achieve higher results in their study. Therefore, these women can often experience social pressure because of their race and sense of identity.

From this point, racism in higher educational institutions prevents African American women from developing their networking contacts and socialization skills (Sinanan, 2016; Vaccaro, 2017). Moreover, this situation can negatively affect the development of students’ research and other academic skills. Researchers noted that when African American women study in predominantly white institutions, they can face open and hidden racism oftener, and this aspect is related to the problems with developing social contacts with the representatives of other ethnic groups (Fountain, 2014; Stevens-Watkins et al., 2014). When African American women represent a minority group in an educational institution, there are more probabilities of facing racism or associated microaggressions.

Educational Advancement Strategies for African American Women

In their studies on African American women’s experiences in post-secondary educational institutions, researchers also examine specific advancement strategies that can be used in order to help these students cope with challenges and barriers (Patterson-Stephens & Vital, 2017; West et al., 2016). Mentoring is viewed as one of the most actively and successfully used strategies in order to assist African American female students on the paths to obtaining a degree.

Mentoring is proposed to be realized in the form of building supportive relationships between a female African American student and another student who prepares for graduating (Commodore et al., 2016; Sinanan, 2016). Therefore, many educational institutions implement formal mentoring programs with strict purposes, tasks, and schedules in addition to informal mentoring practices when relationships and communication between mentors and mentees are not regulated according to the set timetable or formulated goals.

In addition to mentoring, researchers also accentuate positive outcomes associated with the implementation of faculty advising. Thus, faculty advisors are important in order to help students develop as researchers and professionals. Furthermore, such strategies not only help students improve their results in the study, but they also demonstrate the support of an academic community, care, and some empowerment (Croom et al., 2017; Fountain, 2014).

One more approach that is associated with faculty advising is the retention of diverse faculty. According to Patterson-Stephens and Vital (2017), in order to guarantee that African American women receive enough support and assistance at college, it is necessary to recruit and retain diverse professors, tutors, or instructors. This advancement strategy is strictly associated with an organizational transformation that is proposed in many predominantly white institutions. If mentors and faculty advisors are diverse in their culture and race, they can work more effectively with diverse students (Payne & Suddler, 2014; West et al., 2016).

Other educational advancement strategies proposed to African American women can include online or distant learning offered in some institutions. Researchers support this strategy because online learning is often less expensive than traditional learning, and this option can be more appropriate for those African American women who have families and who cannot spend much time on campus (Lin, 2016; Payne & Suddler, 2014). In this case, African American female students receive an opportunity to balance their education, family, social life, and even work.

Some institutions also develop specific First-Year Experiences programs or similar programs that help create supportive settings for students with diverse backgrounds. Researchers stated that these programs also successfully work for African American students (Domingue, 2014; Fountain, 2014).

These programs are oriented to creating specific conditions for students under which they feel like part of an academic community, participate in seminars, and receive all the required assistance. In addition, educational advancement strategies discussed in the recent literature on the problem also include programs and practices that are associated with students’ empowerment and encouragement. These practices are discussed as especially effective during the first years of study in order to help students adapt to new environments, develop their skills, and increase their confidence levels (Hannon, 2016; Graham, 2016; Patterson-Stephens & Vital, 2017).

From this perspective, all the strategies discussed in the literature are oriented to creating supportive and positive atmospheres at colleges or universities for African American female students because this approach will work to address some of the challenges and barriers that are typically viewed by women of color in post-secondary educational institutions.

Education Policy and the Legislative Climate

The numbers regarding African American female students on college campuses have changed significantly during the recent decades. Researchers explain these changes with reference to the improvements in educational policies and certain alterations in a legislative climate regarding the rights of minority groups in the United States (Parker, 2015). Currently, post-secondary educational institutions employ policies according to which minority groups of the population cannot be discriminated against or prevented from obtaining an academic degree because of bias. Equality is promoted at all levels in order to guarantee that African American students or female students have the same rights and opportunities as White students or male peers.

Any cases of discrimination based on race or gender factors are prohibited according to the US laws and institutions’ policies and norms (Patterson-Stephens & Vital, 2017; West et al., 2016). These standards help representatives of minority groups use their right to education. However, the problem is that different forms of hidden discrimination and inequality are still present on campuses.

Today, colleges and universities develop and integrate different programs and policies in order to support ethnically diverse students, female students, students with disabilities, adult students, and other groups. These initiatives work in the context of a legislative framework that is adopted in each state of the country in order to guarantee that all citizens have equal rights and opportunities to successfully receive their higher education (Rose, 2016). The improvement of admission policies, as well as the realization of effective diversity recruitment strategies, is a priority in post-secondary educational institutions (Croom et al., 2017; Sinanan, 2016). As a result, researchers conclude that these trends can contribute to changing the situation related to African American women’s pursuit of higher education for the better.

The Glass Ceiling

The glass ceiling effect is discussed in the literature on women’s experiences in their professional life as a barrier that prevents women’s promotions to higher positions with better payments. These barriers can be actual or perceived by women as a result of their lived experiences (Newman, 2016). According to researchers, glass ceilings can be typical of different types of organizational settings, including educational organizations and companies where women work (Allen & Hughes, 2017; Newman, 2016).

The glass ceiling effect is associated with women’s vision of gender inequality and possible discrimination that prevents them from being promoted. As a result, women experience dissatisfaction, inability to realize their professional potential, and inequality associated with paying for the work they perform in contrast to men’s salaries. In this context, women’s empowerment is minimal (Glass & Cook, 2016; Newman, 2016). Women can be discriminated, and observe glass ceilings in many US organizations in spite of anti-discrimination and diversity policies.

Glass ceilings are also discussed as typical of post-secondary educational institutions because the number of women in the faculty is usually not correlated with the number of female students. This situation is observed especially when the experiences of African American women in colleges and universities are analyzed. The number of African American female leaders in post-secondary educational institutions is still low, and this aspect serves as the illustration for the problem of the glass ceiling, as it is noted by researchers (Allen & Hughes, 2017; Newman, 2016).

However, while discussing glass ceilings, not all researchers agree that observed barriers should be perceived as ceilings, and they introduced the term of glass cliffs that allowed for speaking about certain obstacles for women, including African American women, that can be overcome with the help of some efforts (Glass & Cook, 2016). As a result, the concept of the glass ceiling associated with the discrimination of women in organizations is being revised today.

Affirmative Action

Affirmative action programs were developed in the United States as the response to possible discrimination against minorities in relation to their access to education and employment. The case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) was the first step toward challenging discriminating practices against African Americans’ rights, equality, and access to education (Wolfe & Dilworth, 2015).

The case decision had an effect on all spheres of education, and it contributed to increasing the number of African Americans applying to post-secondary educational institutions. However, privileges for White students were still observed, and affirmative action programs became developed in the 1960s in order to promote equal rights for African Americans as a result of establishing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Fonteneau, 2013). Later, affirmative action programs were supported under the acts of 1991.

The implementation of affirmative action initiatives in organizations led to creating quotas for minority students and employees. As a result, African American women received an opportunity to enter a college or to be employed equally to White women. Today, the principles of affirmative action are still realized in US organizations and educational institutions in terms of recruiting, supporting, developing, and retaining African American women (Wilkins & Wenger, 2014).

However, according to Fonteneau (2013), the actual acceptance of African American female students or tutors by institutions does not mean the integration into the culture of this or that institution, especially in a predominately white institution. As a result, hidden discriminatory practices are still observed in colleges and universities, creating barriers for African American women to developing their potential after entering a college or a university (Wolfe & Dilworth, 2015). Although African American women seem to have all chances to be accepted to an institution or be recruited for a job position, the White privilege principle still works in many organizations.

Community College Leaders

While referring to the topic of leadership in community colleges, researchers discuss the perspectives for taking leadership positions in these colleges by representatives of minority groups and the potential of these colleges for the development of students as leaders. According to Eddy and Mitchell (2017), community colleges can provide both students and educators with many opportunities to become leaders and contribute to a community’s progress. From this perspective, receiving the Associate degree in such institutions, diverse students can also focus on improving their education or on contributing to their community.

In spite of the orientation to developing diverse and minority students, in these post-secondary educational institutions, individuals should overcome the same steps to take leadership positions as in other colleges. Thus, the career path usually starts with the faculty position, and then, it is possible to become the president of a college. The other path is associated with taking the presidency position in another college and being shifted to a community college (Wolfe & Dilworth, 2015).

More than 40% of presidents in community colleges took their position after working as chief academic officers, and about 30% of presidents held the same position in other colleges (Eddy & Mitchell, 2017). In this context, much attention is paid to promoting the leadership of women and people of color in community colleges with the help of national leadership programs, including the initiatives of the American Association of Women in Community Colleges and the Leadership Development Institute for African American Midlevel Administrators.

As a result, in spite of the fact that the majority of community college leaders are still males with the focus on white males, the recently applied programs and initiatives in these colleges have led to changing the perspective for appointing educators as leaders in their institutions. For example, national and state programs promoting diversity in leadership actively work in Maryland, where women take 63% of the presidency positions in comparison to the national average is about 35% (Eddy & Mitchell, 2017). This tendency can be discussed with reference to leadership and the presidency at Prince George’s Community College (PGCC).

Currently, the position of the president at PGCC is held by Dr. Charlene M. Dukes, who became the first female president of this community college among seven other presidents who took this position earlier. This is an example of how PGCC follows the programs adopted in Maryland to support the leadership of women of color in educational institutions. Dr. Dukes also holds the Board Chair position in the American Association of Community Colleges.

Other leadership roles at PGCC are also performed by women of color, including Dr. Rhonda Spells–Fentry as the vice president for Enterprise Technology, Dr. Sandra F. Dunnington as the vice president for Academic Affairs, and Ms. Terri Bacote-Charles as the vice president for Administrative and Financial Services among others (Prince George’s Community College, 2015a). Therefore, it is possible to speak about recent changes in leadership trends in community colleges.

Impact of Education on Employment

The academic degree of a person and his or her access to job positions are viewed as closely related to each other. According to Zimmer (2016), degree completion is directly associated with opening more employment opportunities for a person and potential increases in wages. Furthermore, the researcher accentuated the role of the Associate degree in influencing a person’s perspectives in a job market.

In this context, the academic degree obtained by a person is viewed as the confirmation of his or her knowledge and skills, and employers are usually interested in hiring well-educated individuals to minimize resources required for training them additionally (Glass & Cook, 2016). Therefore, researchers accentuated clear, direct relationships between the level of education or academic degrees and opportunities for being successfully employed (Glass & Cook, 2016; Zimmer, 2016).

Much research is concentrated on studying tendencies for African American students and women of color in particular. Researchers found that African American females with academic degrees have more opportunities to be employed than African American women with unaccomplished degrees. If women of color receive a good higher education, they are considered attractive employees in those communities where African Americans represent the majority.

Researchers claimed that there is a high demand for African American professionals in many communities with diverse populations, but comparably low educational levels of community members prevent these groups of people from development (Alexander & Hermann, 2016; Davis & Maldonado, 2015). Therefore, the necessity for education among people of color is accentuated by many scholars.

However, the problem determined with reference to the literature is that there is still a gap related to the comparison of employment opportunities for White and non-White individuals. According to Quillian, Pager, Hexel, and Midtbøen (2017), the education of an African American often cannot significantly influence the decision of a recruiter in spite of referring to affirmative action and anti-discriminatory policies.

Some stereotypes, including biases regarding the education of African Americans, can still influence the final decisions of human resource managers on the selection of this or that candidate. The problem is that direct discrimination was effectively addressed by the legal acts of the 1960s and later periods, but the discrimination that is observed today cannot be detected so easily. Nevertheless, researchers are inclined to observe positive correlations between the education of people of color with the focus on women and their opportunities for career development (Quillian et al., 2017; Zimmer, 2016).

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

The decision proclaimed by the court regarding Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) influenced the access of African Americans to education according to the principle of equal opportunity. Despite the fact the decision was directly related to high school issues, it also affected higher education in the country because of debating the segregation rule in American society. The Topeka Board of Education was discussed as opposing African American children’s rights to have equal opportunities to receive education similarly to White children.

Those schools that were reserved for non-White children seemed to propose only inappropriate services for students. According to the court’s decision of 1954, significant changes in used segregation laws were required with the focus on improving the situation in public schools (López & Burciaga, 2014; Rose, 2016). Although the ruling was oriented to addressing the segregation laws, actual changes to affect racial discrimination in educational institutions were not immediate.

However, researchers stated that the Brown ruling contributed to altering the public’s vision of African Americans’ need for education, and the appearance of policies and programs supporting the education of people of color are associated with this case. African Americans continued to protest against discrimination at school and the implementation of racially discriminatory practices.

As a result, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed in response to these protests associated with the movement for civil rights in the United States, and policies regarding the enrollment of African Americans to educational institutions of the country were changed (Lash & Ratcliffe, 2014; Parker, 2015). Therefore, the current presence of people of color, including women of color, in higher educational institutions is directly associated with the Brown ruling and following movements against discrimination in all social fields.

The Theoretical Framework of the Study that Supports the Research Theory

The discussed theories, including the Critical Race, Social Learning, and Feminist theories, represent the theoretical framework for this phenomenological study. Therefore, it is important to explain why these theories have been selected as the background for the study and how they can support the topic of this research. The theoretical principles of phenomenological research should also be discussed in this context as they add to the developed theoretical framework. Thus, it is important to note that Critical Race Theory, Social Learning Theory, and Feminist Theory, as well as the phenomenological theory, were actively applied by other researchers to studying the topic of African American women’s access to higher education, and this allows for creating an effective theoretical framework for this research.

Critical Race Theory is one of the theoretical perspectives that support the current research because it is effective in explaining why African American women can face certain difficulties on their paths to higher education through the lenses of their race. The reason for choosing this theory is that its assumptions cover such problematic areas as racial discrimination, racial disparities, prejudice, and exclusion, which are important to be discussed while analyzing African American women’s experiences in higher educational institutions (Howard & Navarro, 2016; Ledesma & Calderón, 2015). Applying this theory to the current study, it is possible to understand how the perspectives of race and ethnicity can influence African American women’s attempts to receive a higher education, as well as their interactions in social groups.

Social Learning Theory is selected for this study as an appropriate theoretical model because it can explain African American women’s experiences in higher educational institutions from several viewpoints. The strength of this theory is that it demonstrates how female students can succeed when they adapt to new educational environments and learn patterns followed for interactions in new settings (Hanna et al., 2013; Kattari, 2015).

If adaptation is not successful, such students experience problems. Another perspective is that peers and educators in different types of post-secondary institutions model their behaviors depending on patterns they observe and learn. Thus, this theory is also important to explain the process when groups of students or educators begin to discriminate against minority students while reflecting behaviors of each other.

One more important social concept to explain in the study is the concept of gender. Feminist Theory, which is grounded in this concept, is selected for this study because it can be used to clarify how students’ gender can influence their path to higher education, what barriers can be observed on this path, and why men can be viewed as more advantaged than women when they focus on obtaining educational degrees and developing careers (Carastathis, 2014; Friedman & Ayres, 2013). The application of Feminist Theory to the study as part of the theoretical framework is important to provide the background for minority students’ experiences in higher educational institutions with the focus on the aspect of gender.

It is also necessary to refer to the phenomenological theory as part of the framework to support the study. The formulation of the principles of phenomenology depends on the philosophical teachings of such theorists as Husserl and Heidegger (Willis, Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, & Cohen, 2016). Thus, Husserl viewed phenomenology as a tool to investigate lived experiences of individuals, and Heidegger focused on interpreting these experiences (Matua & Van Der Wal, 2015; Sousa, 2014).

In this study, the phenomenological approach is applied to examine lived experiences and perceptions of African American female students related to their study in a community college (McCoy, 2014). This framework is important to provide the researcher with opportunities to study barriers faced by African American female students with reference to their specific experiences.

References

Alexander, Q. R., & Hermann, M. A. (2016). African-American women’s experiences in graduate science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education at a predominantly white university: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 9(4), 307-314.

Allen, P. L., & Hughes, J. D. (2017). A multi-generational study of aspiring African American female superintendents in Texas. Contemporary Issues in Educational Leadership, 2(3), 1-13.

Baber, L. D. (2012). A qualitative inquiry on the multidimensional racial development among first-year African American college students attending a predominately white institution. The Journal of Negro Education, 81(1), 67-81.

Bartman, C. C. (2015). African American women in higher education: Issues and support strategies. College Student Affairs Leadership, 2(2), 1-7.

Carastathis, A. (2014). The concept of intersectionality in feminist theory. Philosophy Compass, 9(5), 304-314.

Charleston, L. J. (2012). A qualitative investigation of African Americans’ decision to pursue computing science degrees: Implications for cultivating career choice and aspiration. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5(1), 222–243.

Collins, P. H. (2015). No guarantees: Symposium on black feminist thought. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(13), 2349-2354.

Commodore, F., Freeman, S., Gasman, M., & Carter, C. M. (2016). “How it’s done”: The role of mentoring and advice in preparing the next generation of historically black college and university presidents. Education Sciences, 6(2), 19-28.

Croom, N. N., Beatty, C. C., Acker, L. D., & Butler, M. (2017). Exploring undergraduate black womyn’s motivations for engaging in “sister circle” organizations. NASPA Journal about Women in Higher Education, 10(2), 216-228.

Davis, D. R., & Maldonado, C. (2015). Shattering the glass ceiling: The leadership development of African American women in higher education. Advancing Women in Leadership, 35(1), 48-64.

Domingue, A. D. (2014). “Give light and people will find a way”: Black women college student leadership experiences with oppression at predominantly white institutions. Web.

Eddy, P. L., & Mitchell, R. L. G. (2017). Preparing community college leaders to meet tomorrow’s challenges. Journal for the Study of Postsecondary and Tertiary Education, 2, 127-145.

Felder, P., & Barker, M. (2013). Extending bell’s concept of interest convergence: A framework for understanding the African American doctoral student experience. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 8(1), 2-20.

Fenwick, J., & McMillan, J. (2014). Public administration: What is it, why teach it and does it matter? Teaching Public Administration, 32(2), 194-204.

Fonteneau, D. Y. (2013). Dismantling glass ceilings: Ethical challenges to impasse in the academy. Journal of the International Association for the Study of the Global Achievement Gap, 1, 66-75.

Fountain, S. L. (2014). Stopping out: Experiences of African American females at a Midwestern community college. Web.

Friedman, C. K., & Ayres, M. (2013). Predictors of feminist activism among sexual-minority and heterosexual college women. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(12), 1726-1744.

Garibaldi, A. (2014). The expanding gender and racial gap in American higher education. The Journal of Negro Education, 83(3), 371-384.

Glass, C., & Cook, A. (2016). Leading at the top: Understanding women’s challenges above the glass ceiling. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 51-63.

Graham, A. (2016). Womanist preservation: An analysis of Black women’s spiritual coping. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 35(1), 106-117.

Hanna, R. C., Crittenden, V. L., & Crittenden, W. F. (2013). Social learning theory: A multicultural study of influences on ethical behavior. Journal of Marketing Education, 35(1), 18-25.

Hannon, C. R. (2016). Stress, coping, and well-being of African American college women: A grounded theory study. Web.

Harris, J. C. (2017). Multiracial women students and racial stereotypes on the college campus. Journal of College Student Development, 58(4), 475-491.

Howard, T. C., & Navarro, O. (2016). Critical race theory 20 years later: Where do we go from here? Urban Education, 51(3), 253-273.

Iloh, C., & Toldson, I. (2013). Black students in 21st century higher education: A closer look at for-profit and community colleges. The Journal of Negro Education, 82(3), 205-358.

Jackson, D. L. (2013). A balancing act: Impacting and initiating the success of African American female community college transfer students in STEM into the HBCU environment. The Journal of Negro Education, 82(3), 255-271.

Kattari, S. K. (2015). Examining ableism in higher education through social dominance theory and social learning theory. Innovative Higher Education, 40(5), 375-386.

Lash, M., & Ratcliffe, M. (2014). The journey of an African American teacher before and after Brown v. Board of Education. The Journal of Negro Education, 83(3), 327-337.

Ledesma, M. C., & Calderón, D. (2015). Critical race theory in education: A review of past literature and a look to the future. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 206-222.

Lin, X. (2016). Barriers and challenges of female adult students enrolled in higher education: A literature review. Higher Education Studies, 6(2), 119-126.

López, G. R., & Burciaga, R. (2014). The troublesome legacy of Brown v. Board of Education. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50(5), 796-811.

Matua, G. A., & Van Der Wal, D. M. (2015). Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches. Nurse Researcher, 22(6), 22-27.

Mayer, C. H., Surtee, S., & Barnard, A. (2015). Women leaders in higher education: A psycho-spiritual perspective. South African Journal of Psychology, 45(1), 102-115.

McCoy, D. (2014). A phenomenological approach to understanding first-generation college students’ of color transitions to one “extreme” predominantly white institution. College Student Affairs Journal, 32(1), 155-169.

Montgomery, B. L., Dodson, J. E., & Johnson, S. M. (2014). Guiding the way: Mentoring graduate students and junior faculty for sustainable academic careers. SAGE Open, 4(4), 1-11.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2016). Table 302.60. Percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by level of institution and sex and race/ethnicity of student: 1970 through 2015. Web.

Newman, B. J. (2016). Breaking the glass ceiling: Local gender‐based earnings inequality and women’s belief in the American dream. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 1006-1025.

Parker, P. (2015). The historical role of women in higher education. Administrative Issues Journal, 5(1), 3-9.

Patterson-Stephens, S. M., & Vital, L. M. (2017). Black doctoral women: Exploring barriers and facilitators of success in graduate education. Academic Perspectives in Higher Education, 3(1), 1-35.

Payne, Y. A., & Suddler, C. (2014). Cope, conform, or resist? Functions of a Black American identity at a predominantly White university. Equity & Excellence in Education, 47(3), 385-403.

Prince George’s Community College. (2015a). Senior team. Web.

Prince George’s Community College. (2015b). Student success programs. Web.

Quillian, L., Pager, D., Hexel, O., & Midtbøen, A. H. (2017). Meta-analysis of field experiments shows no change in racial discrimination in hiring over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(41), 10870-10875.

Ringeling, A. (2015). How public is public administration? A constitutional approach of publicness. Teaching Public Administration, 33(3), 292-312.

Rose, D. (2016). The public policy roots of women’s increasing college degree attainment: The National Defense Education Act of 1958 and the Higher Education Act of 1965. Studies in American Political Development, 30(1), 62-93.

Savas, G. (2014). Understanding critical race theory as a framework in higher educational research. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 35(4), 506-522.

Shand, R., & Howell, K. E. (2015). From the classics to the cuts: Valuing teaching public administration as a public good. Teaching Public Administration, 33(3), 211-220.

Sinanan, A. (2016). The value and necessity of mentoring African American college students at PWI’s. Journal of Pan African Studies, 9(8), 155-166.

Sousa, D. (2014). Validation in qualitative research: General aspects and specificities of the descriptive phenomenological method. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(2), 211-227.

Stevens-Watkins, D., Perry, B., Pullen, E., Jewell, J., & Oser, C. B. (2014). Examining the associations of racism, sexism, and stressful life events on psychological distress among African-American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(4), 561-569.

Strayhorn, T. L. (2015). Factors influencing Black males’ preparation for college and success in STEM majors: A mixed methods study. Western Journal of Black Studies, 39(1), 45-63.

Thomas, J. C., Wolters, C., Horn, C., & Kennedy, H. (2014). Examining relevant influences on the persistence of African-American college students at a diverse urban university. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 15(4), 551-573.

Vaccaro, A. (2017). “Trying to act like racism is not there”: Women of color at a predominantly white women’s college challenging dominant ideologies by exposing racial microaggressions. NASPA Journal About Women in Higher Education, 10(3), 262-280.

Wallace, D., Budden, M., Juban, R., & Budden, C. (2014). Making it to the top: Have women and minorities attained equality as higher education leaders? Journal of Diversity Management, 9(1), 83-88.

West, L. M., Donovan, R. A., & Daniel, A. R. (2016). The price of strength: Black college women’s perspectives on the strong black woman stereotype. Women & Therapy, 39(3-4), 390-412.

Wilkins, V. M., & Wenger, J. B. (2014). Belief in a just world and attitudes toward affirmative action. Policy Studies Journal, 42(3), 325-343.