Introduction

In the last century, organizations have faced unique challenges that stem from experiencing unique changes in their internal and external environments (Williams 2002, 4). Some of the most notable changes include global economic uncertainties, changes in consumer tastes and preferences, and technological changes (among other issues) (Williams 2002, 6). While some of these changes may appear circumstantial, the failure of organizations to adapt to the changing environment and the persistent presence of retrogressive organizational cultures, which condone such weaknesses, exacerbate some of these problems (Dashwood 2012, 52-53).

Poor organizational performance is a problem that emanates from an inherently flawed organizational culture (Schein 2010, 177). However, many chief executive officers (CEOs) ignore this perspective and instead choose to focus on managing some of the most common management dilemmas, such as investing vs. holding, ethics vs. profits, maximization of employee welfare vs. maximization of investor returns, and local vs. global investment decisions (among other organizational dilemmas) (Dashwood 2012, 4-6). In this regard, they fail to realize that addressing part of the problem of organizational culture stems from understanding its dynamics and structure.

Different researchers have used different models to explore and explain organizational cultures and structures (O’Donnell and Boyle 2008, 16). For example, two scholars, Cameron and Quinn (2011, 7), analyzed organizational culture using the organizational culture assessment instrument, which uses a competing value model to explain different tenets of cultural analysis. However, most of these analogies are typologies that fail to capture the true essence and depth of organizational culture.

For example, they fail to grasp the full complexity of inherent organizational dynamics by oversimplifying organizational culture, thereby providing us with cultural categories that may be irrelevant to our understanding of cultural dynamics. Consequently, as readers, we develop a limited perspective of culture in organizations, as we confine our understanding to only a few tenets of cultural understanding (thereby missing the “big picture”).

The narrow focus on cultural dynamics also limits our ability to comprehend complex patterns of cultural relationships within organizations. Therefore, existing models of cultural frameworks provide us with a limited understanding of organizational culture. Nonetheless, the application of the tensegrity concept in different scientific fields presents us with a plausible framework for broadening our understanding of culture.

Coined by Buckminster Fuller, in the 1960s, tensegrity is a structural principle, which explains how different and isolated components suspend in a compressed state (Motro 2003, 213). In the tensegrity model, compressed elements often do not touch each other (floating compression), but align in one delineated spatial system. Researchers have applied the concept in different scientific disciplines (Zhang and Ohsaki 2015, 6).

Architecture was among the first disciplines to adopt the concept (Simitch and Warke 2014, 1). Spearheaded by the works of Maciej Gintowt and Maciej Krasiński (cited in Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541), experts developed structures that demonstrated the principles of the tensegrity structure. Most of its applications emerged in the 1960s (Zhang and Ohsaki 2015, 6-8). Biology is also another field that embraced the concept of tensegrity. Researchers in this field have used it to explain different bodily functions and structures (Motro 2003, 213). The adoption of the tensegrity model in biology birthed the concept of biotensegrity.

Biotensegrity is a relatively new approach of understanding how different aspects of the human body work and function. This concept stems from the understanding that different biological systems demonstrate the principles of tensegrity because the human body structure does not necessarily pass off different load elements on each other (Motro 2003, 213). Doctor Stephen Levin (cited in Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541) was among the first scholars to explore the concept of biotensegrity in this regard. He applied this approach in orthopedic surgery (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541).

Tom Flemons is another revolutionary scholar who investigated this concept and applied it in his depictions of the human anatomy (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541). Historians documented some of his earliest works in the mid 1980s (Zhang and Ohsaki 2015, 6-8). They mostly included spatial representations of the human spine and the leg structure (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541).

Comprehensively, researchers have used the biotensegrity model to explain different aspects of the human biological structure. While this field of research (biotensegrity) is relatively underdeveloped, some researchers have used this concept to explain different dynamics of organizational performance (Singh and Ananthanarayanan 2013, 106). However, there have been minimal attempts by researchers to explain the relationship between the biotensegrity model and organizational culture. This research gap exists despite the potential similarities between organizational culture and the biotensegrity model, which this paper will demonstrate. The underlying research questions for this study are as follows

Research Questions

- How does the biotensegrity model represent organizational culture?

- If the human system is a biotensegrity structure, why can an organization not have one?

This paper investigates the adoption of the biotensegrity model to organizational culture. It transcends the narrow focus of organizational dynamics presented by existing models, such as the Denison Organizational culture model and the Hofstede cultural model, to present a broader understanding of culture in organizations by arguing that the biotensegrity model explains organizational culture. This study also postulates that the similarity between the biotensegrity model and organizational culture stems from the similarities in characteristics between organizational culture and biotensegrity.

Tensegrity

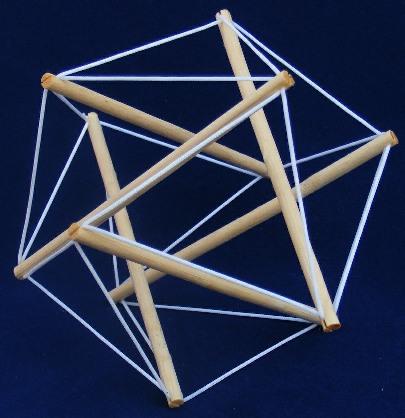

Buckminster Fuller (cited in Simitch and Warke 2014, 16) coined the term tensegrity, in the early 1960s, to explain a set of components under compression. He said it refers to the creation of structures, which draw their strength from the combination of united, but compressed structures (Simitch and Warke 2014, 76). The diagram below represents an example of this structure

As highlighted in the introduction, experts have applied the tensegrity concept in different scientific fields, including architecture and biology (biotensegrity). Generally, in biology, biotensegrity refers to the application of tensegrity principles to the human body (Hendryx 2014, 10). Researchers in this field have often used biotensegrity to explain the working mechanisms of different biological structures, such as muscles, ligaments and tendons (Hendryx 2014, 10). Some of them have also used it to explain the working mechanisms of rigid and elastic cell membranes (Scarr 2012, 53). The basic principle of biotensegrity stems from the understanding that nature always creates the simplest and most efficient anatomical structures (Scarr 2008, 80).

Tensegrity as a Model of Anatomy

Fuller’s understanding of tensegrity partly stems from his conception of Kenneth Snelson’s works, which depicted the human anatomy through sculptures. Hellen (another researcher cited in Ingber et al. 2000, 1663) has also contributed to this discussion by presenting her understanding of the human anatomical model as a structure held together by tissues and bones. Although some of these conceptions of the human anatomical model may differ in content and context, it is almost impossible to understand them without comprehending the concept of tensegrity in the first place. Similarly, it is also difficult to picture the model of tensegrity without visualizing how tension and compression forces work together in the tensegrity structure (Ingber 1998, 48). Fuller and Snelson’s works (cited in Ingber et al. 2000, 1663) have affirmed this assertion because they have helped us to visualize the differences between tension and compression.

Patterson (2011, 56) says that his view of tensegrity developed from years of reviewing the works of Fuller. He says the tensegrity structure maintains stability and form by interacting with other elements, or structures, that resist the pressure of compression (Patterson 2011, 56). Although Ingber et al. (2000, 1663) explain tensegrity through an architectural lens; they also use the human anatomy to explain the same. Referring to this fact, they say,

“To visualize tensegrity at work, think of the human body: it stabilizes its shape by interconnecting multiple compression-resistant bones with a continuous series of tensile muscles, tendons, and ligaments, and its stiffness can vary depending on the tone (prestress) in its muscles” (Ingber et al. 2000, 1663).

If a person wants to lift a hand, tension occurs in the elbow muscles and even at the toes. However, since the body is multimodular and hierarchical, damage to the Achilles tendon would mean that a person loses coordination of certain aspects of their body movements, without necessarily losing their natural balance. The same movements could occur when a person breathes because Ingber et al. (2000) says,

“Every time I breath in, causing the muscles of my neck and chest to pull out on my lattice of ribs, my lung expands, alveoli open, taught bands of elastin in the extracellular matrix (ECM) relax, buckled bundles of cross-linked (stiffened) collagen filaments straighten, basement membranes tighten, and the adherent cells and cytoskeletal filaments feel the pull. However, nothing breaks and the deformation is reversible” (1664).

Based on the above statements, many researchers say that tensegrity provides a model for explaining most human bodily functions (Ingber 1998, 48).

Application of the Tensegrity Model to Biological Organisms

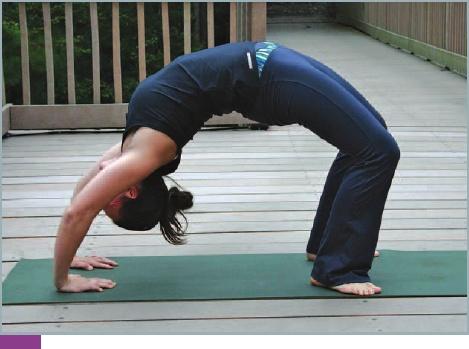

The earliest applications of the tensegrity model to biological systems focused on the human spinal cord and its transmission of information to other parts of the body. To affirm this view, Kosciejew (2012, 35) says the human spinal cord cannot necessarily function as a column because it has an indisputable flexibility that would prevent a person from generally dismissing it as so. To understand the merit of this argument, simply, one should picture the pose of a person doing Yoga as depicted below.

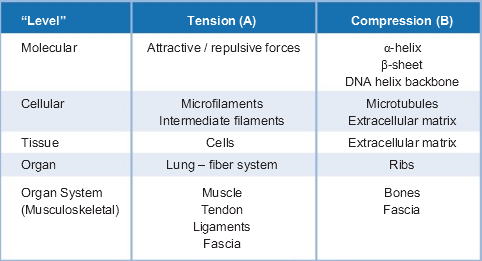

According to the picture above, Swanson (2013, 37) finds that the human spine could bend to adopt the shape of a wheel. Some researchers say this observation marked the first attempt of researchers to merge elements of the tensegrity architecture to biology (Ingber et al. 2000, 1663). Studies that adopted this analogy produced their findings in the early 1970s (Swanson 2013, 34- 37). With advancements in science and microbiology, scientists started using the tensegrity structure to explain cell functions (Ingber et al. 2000, 1663). Three decades of further advancements in medical research have seen the application of tensegrity spread to the understanding of human tissues and organ functions. The table below shows how researchers have used the tensegrity structure to explain the molecular, cellular, tissue, and musculoskeletal functions of the human body.

The diagram above shows the different forces of tension and compressive elements of biological functions that underlie the functions of the human body. The focus of this study is on the musculoskeletal level. The forces of tension that characterize this level come from the muscles, tendons, ligaments and fascia. Compression occurs in the bones and fascia. Nonetheless, according to Kosciejew (2012, 24), tensegrity applies to all scales of the human body.

The biotensegrity theory postulates that human bones act as discontinuous compression-resistant struts within the wider analysis of the biotensegrity model (Simitch and Warke 2014, 56). The muscles, tendons and ligaments act as the medium for transmitting the tension forces that make up the entire model. Researchers have also shown that the facial system can act as a tension-generating mechanism and a compression-resistant system as well (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541).

In this regard, the musculoskeletal system emerges as a pre-stressed biotensegrity system (where pre-stress occurs when there is an increase in muscle tension) (Simitch and Warke 2014, 55). The increase in muscle tension often generates movement. Researchers that have further investigated the musculoskeletal structure have also pointed out that individual components of the system are biotensegrity structures as well (Stamenovic, Wang and Ingber 2009, 1093; Swanson 2013, 37-38). For example, some studies have looked at the distal radioulner joint as one such example (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541).

Other researchers have also modeled other parts of the human body on the same structure (Zhang and Ohsaki 2015, 6-8). For example, Levin (a medical researcher) has designed the human pelvis on the tensegrity model (Zhang and Ohsaki 2015, 6-8). Researchers have also modeled the mammalian spine on the same model (Swanson 2013, 38). For millions of years, it has assumed a horizontal position, but evolution made it assume a vertical position (Ingber et al. 2000, 1663).

An analysis of a Giraffe’s neck in the horizontal position reveals that the stability of the spine should be subject to another force besides gravity. A deeper analysis of the human spine during extreme exercises, such as Yoga and gymnastics, show the dynamic movements that the spine can accommodate. These movements also show that evolution had to develop a spine that was lightweight, dynamic, and flexible enough to accommodate the physical functions of the body and, at the same time, protect the human neurological system (Motro 2003, 23-25).

The tensegrity model demonstrates how the spine could accommodate all these attributes because all parts of a tensegrity model work as a system (Stamenovic, Wang and Ingber 2009, 1093). Some properties of the system that allow it to accommodate varied stresses include flexibility and adaptability. Although it appears as though the tensegrity model is the functional unit of the body, as culture is the functional unit of an organization, few researchers have investigated this claim.

William Sutherland Model

The works of William Garner Sutherland provide a conceptual framework for our understanding of the application of the biotensegrity model to organizational culture. In 1929, through this framework, he presented the idea of osteopathy in the cranial system (Theodore 2009, 100). He termed his concept as “osteopathy in the cranial field.” At the core of Sutherland’s concept is the understanding that the bony cranium could accommodate respiratory activities (Burns, David and Christine 2008, 9-10). His definition of the primary respiratory mechanism has three concepts outlined below:

Primary

This concept is the first in Sutherland’s model of the cranial system because it underlies all of life’s processes. He says it gives dynamism, form and substance to orthopedic structures and biological elements (Theodore 2009, 100).

Respiration

This is the trigger of human breadth. Acting as a foundation for metabolism, it gives life to tissues through inhalation and exhalation phases (Burns, David and Christine 2008, 9-10).

Mechanism

The concept of mechanism in Sutherland’s model presents the primary respiratory mechanism as a sum of many parts, which create a whole. The “whole” is greater than the sum of the different parts of the human body (Burns, David and Christine 2008, 9-10).

The different concepts of the primary respiratory system exist as functional components of the larger human biological system. In this regard, the primary respiratory system manifests itself in the whole body and throughout most parts of nature. Research studies that have investigated this issue have suggested that the intrinsic motion of the respiratory system is a symbol of life itself (Burns, David and Christine 2008, 9-10).

Parts of the Primary Respiratory Mechanism

The five components of the primary respiratory mechanism express involuntary physiological motions that characterize the functions of the central nervous system and its associated anatomical structures and functions (Burns, David and Christine 2008, 9-10). They include the inherent mobility of the brain and spinal cord, the fluctuation of the cerebrospinal fluid, the dynamic shifting of tensions in the dura mater, the articular mobility of the cranial bones, and the respiratory motion of sacrum (Theodore 2009, 100-102).

This paper would apply these parts of the primary respiratory mechanism to our understanding of biotensegrity and organization culture. Indeed, it would provide us with a critical understanding of key concepts and issues pertaining to the research topic. Similarly, it would provide us with an abstract understanding of the relationship between organizational culture and the biotensegrity model. Key concepts and theories regarding this relationship also appear in some tenets of the Sutherland model. Its findings will guide us in answering the key research questions of this paper, which seek to find out how the biotensegrity model represents organizational culture and investigate if an organization can have a biotensegrity structure.

Relationship between Organizational Culture and the Biotensegrity Model

Schein (2010, 128) says that since the start of the industrial revolution, companies have grown from small stalls and family-run enterprises to large corporations that have a global presence in multiple continents. The functions of these corporations have also grown to unimaginable scales because one industry could control vast resources and provide some of the most vital goods and services needed to support the global economy (Schein 2010, 128). Williams (2002) adds that the capability of today’s global enterprises has grown on the back of increased complexity in the operations of multinational companies. A few researchers have noted the complexity of today’s companies, as a comparison to the complexity of the human anatomical structure and, most importantly, the complexity of the biological systems that support it (Zhang and Ohsaki 2015, 6-8).

In this regard, some of them say there are sufficient grounds to compare the biotensegrity structure to organizational functions (Simitch and Warke 2014, 46). However, doing so requires a holistic understanding of the complexity of the human anatomy and its comparison to the complexity of today’s organizational structures. Man’s attempt to design efficient organizational structures and the inherently efficient nature of the human biological system shows the potential comparative analysis of the human system and organizational systems. Tensegrity structures could provide a conceptual understanding of the human biological and anatomical systems.

This model has not only demonstrated that the human body is organized by forces under tension (and not compression forces), but also showed that nature builds her structures from a subatomic level to a cosmic level (Simitch and Warke 2014, 45). Some of these insights have contributed to our understanding of how well we should take care of our bodies and how to do so in the first place.

Organizational Culture

People often have different definitions of culture. However, they rarely dispute its influence on organizational processes. It is important to understand organizational culture in organizational processes because it helps us to understand other key elements of an organization, such as structure and operating systems. Simply, Schein (2010, 177) defines organizational culture as how people “do things” in an organization. This statement aligns with Aristotle’s views on human behavior when he said human beings are products of what they repeatedly do (Schein 2010, 177). Richard Perrin (cited in Schein 2010) adopts a more critical view of the concept when he says organizational culture is “is the sum of values and rituals which serve as ‘glue’ to integrate the members of the organization” (3). According to Janićijević (2013), culture is

“A system of assumptions, values, norms, and attitudes, manifested through symbols which the members of an organization have developed and adopted through mutual experience and which help them determine the meaning of the world around them, and the way they behave in it” (36).

The above definitions reinforce a common understanding, in business circles, which demonstrate that repetition is at the center of organizational culture.

In the last century, many researchers have focused on understanding, or explaining, how culture affects different aspects of organizational performance (Schein 2010, 177; Williams 2002, 34). Experiential literatures that have talked about organizational culture and productivity stem from the works of researchers who drew a relationship between organizational culture and change (Schein 2010, 177-178). For example, in 1983, R.M Kanter, a human resource researcher, showed that most companies, which adopted progressive human resource cultures, registered a better performance than those that did not adopt the same practices (Kusluvan 2003, 605). A deeper analysis of this fact will appear in later sections of this report.

Impact of Culture on Organizational Structure and Performance

Based on the influence of organizational culture on organizational performance, Kusluvan (2003, 31-32) finds that organizational culture is both symbolic and cognitive in nature because it affects people’s attitudes and behaviors, while at the same time creating an organization’s image. Janićijević (2013, 35-37) adds that organizational culture affects peoples’ interpretations of the world and outlines how they should behave in it. The cognitive element of organizational culture dictates how employees attach meaning to a specific organizational phenomenon and their reaction to decisions that respond to these issues (Janićijević 2013, 35-37).

Schein (2010, 177-178) says the symbolic element of organizational culture provides a comprehensive representation of the cognitive attributes of organizational culture. For example, semantic and behavioral attributes of organizational culture encapsulate the tenets of organizational culture. Similar to this analogy, Janićijević (2013) says, “The significance of organizational culture emerges from the fact that, by imposing a set of assumptions and values, it creates a frame of reference for the perceptions, interpretations, and actions of the organization’s members behave in it” (37).

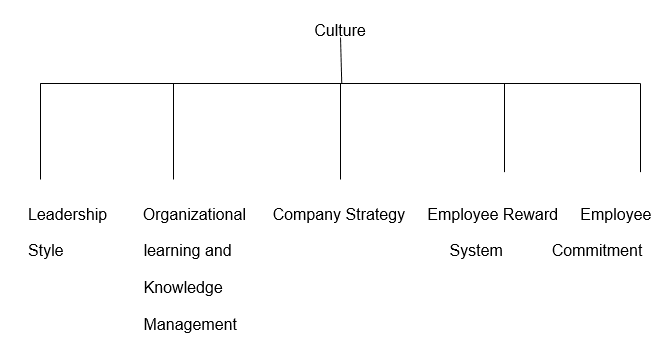

Based on this assertion, Schein (2010, 177) says culture not only influences the processes that go on in an organization; it also determines the nature of its performance. A deeper understanding of this statement appears in the works of Schein (2010, 178) who argues that the mental framework provided by organizational culture affects an organization’s leadership style, management structure, reward and compensation systems, company strategy, and other aspects of corporate governance.

Generally, organizational culture affects the connections between employees and their organizations. Within this framework of reference, correctly, Schein (2010, 177) assumes that organizational culture affects an organization’s structure. The transmission framework happens through cultural influences on management, which eventually affect how managers and leaders shape organizational structures. Some researchers have pointed out that organizational structures are cultural symbols of different institutions (Sims and Quatro 2015, 253-254). This analogy premises on the purposive nature of organizational structures.

The intention of designing organizational structures to align with organizational cultures means that the managers have designed it in a format that would help them to achieve their organizational objectives (Sims and Quatro 2015, 253-254). The differentiation and integration of different stakeholders in an organization’s structure ensure the rationality of the organizational structure and its relationship with organizational culture. The process of differentiation outlines the ability of the organizational structure to differentiate operational and managerial processes.

Relationship between Organizational Culture and Structure

Some researchers have claimed the impossibility of understanding organizational culture without understanding its effects on organizational structure (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541). This is why some of them have struggled to understand the role of culture in organizational processes. According to Kortmann (2012, 57), organizations may have trouble realizing their goals if they do not comprehend how their structures affect their goals. Since organizations cannot run without people, those that do not pay a close attention to their organizational structures will naturally realize the creation of informal organizational structures (Schein 2010, 200).

This outcome would eventually lead to the creation of different behaviors, attitudes and perceptions that would ultimately lead to the development of organizational cultures (Kortmann 2012, 87). Therefore, when employees work together to realize organizational objectives, they develop specific ways of interaction that later form part of organizational culture. The culture may develop either knowingly or unknowingly. Partly, organizational structure may define the organizational culture and similarly, the organizational culture may affect the organizational structure (Schein 2010, 177).

Some researchers have taken this analysis further and remarked that organizational structure may provide a framework for implementing organizational culture (Cameron and Quinn 2011, 7). In this regard, Kortmann (2012, 12) cautions managers to be wary of the causal relationship between organizational structure and culture because if the organizational culture fails, the structure is likely to follow suit.

Some researchers have further explained the relationship between organizational culture and structure by drawing a causal relationship between the two, with the understanding that they both affect organizational performance (Cameron and Quinn 2011, 7). At a conceptual level, some researchers, such as Sims and Quatro (2015, 253-254), say the causal relationship between the two stems from the mechanism that organizational culture affects organizational structure. They say this structure affects the maintenance, strength and potential for organizational processes to change (Sims and Quatro 2015, 253-254).

Existing classifications of organizational culture and structure also reinforce this fact because they demonstrate that the two factors forge a mutually interdependent relationship. To affirm this relationship, researchers have generated different hypotheses about the two factors (Schein 2010, 200). These hypotheses have often hinged on the understanding of good and bad corporate cultures.

Good and Bad Cultures

Organizational culture often leads to both positive and negative organizational outcomes. The continuum of success and failure mainly depends on whether the culture is good or bad. Bad cultures often impede progress and lead to poor organizational outcomes (Schein 2010, 177-178). Comparatively, good cultures promote organizational processes and lead to positive outcomes. Cameron and Quinn (2011, 7-10) say that bad organizational cultures have led to employee frustration, bad attitudes among employees, and high employee turnover rates. Comparatively, McCarthy (2012, 78) says organizational culture could mark the start of close cooperation among employees, or mark the start of mistrust among employees. In this regard, some researchers have tried to explore why organizations fail on the premise of poor organizational culture (Cameron and Quinn 2011, 7-10).

Ideally, this should not be the case because organizational culture should improve organizational productivity and efficiency (Schein 2010, 177-178). It is also supposed to draw them closer to realizing their goals, compared to a situation where culture is ineffective (Cameron and Quinn 2011, 7-10). Researchers have revealed that the failure to address leadership issues, lack of core values within the system, managerial indifference, poor communication, and favoritism are some of the most common causes of cultural breakdowns in organizations (McCarthy 2012, 53). Nonetheless, poor leadership has emerged as a key area of concern in explaining cultural breakdowns in different organizations. Indeed, few researchers dispute the important role played by good leadership in steering organizations towards corporate success.

In fact, Schein (2010, 376) says that if good leadership prevails throughout all cadres of an organization, all employees can feel it. Comparatively, organizations that have poor leadership suffer from poor organizational outcomes because bad organizational practices intoxicate employees and impede their success in meeting their organizational goals (Cameron and Quinn 2011, 7-10). McCarthy (2012, 71-73) has used the relationship between leadership and organizational culture to explain this finding by saying that with the adoption of good leadership, corporate culture is not forced; instead, it grows and develops incrementally.

Conversely, poor leadership often leads to a breakdown in organizational culture because employees do not communicate openly and frequently in such environments (Cameron and Quinn 2011, 7-10). Furthermore, rarely do they understand the organization’s vision, or strategies for meeting its goals. The Enron case study below is an example of the effects of bad organizational cultures

Example of Company with Bad Culture – Enron Case Study

Formed in 1985, by Kenneth Lay, Enron was among the biggest and most successful corporations in America. It had varied interests in the energy sector where it made most of its profits (the company had a presence in many economic sectors) (Johnson 2003, 45).

A few years of operation saw Enron hire Jeffrey Skillings and a group of other executives who used dubious accounting practices and exploited the company’s internal audit loopholes to hide billions of dollars in losses (Johnson 2003, 45-47). Coupled with the failure of management to exercise proper scrutiny, or shoulder the responsibility for its unethical practices, the company filed for bankruptcy in 2001 (Johnson 2003, 45-47). After the collapse of the company, the government indicted some of its directors and imprisoned others for different charges of corporate malpractice.

The collapse of Enron was a case of poor leadership. It led to the destruction of the organization’s core values and principles of integrity and honesty. This scandal is among the world’s largest corporate fraud cases, which was a product of the abuse of power and privilege, including the manipulation of financial statements. The company’s leadership also had no regard for its employees and put their interests above those of others.

Example of Company with Good Culture – Google

Google is a global tech company, based in California USA. It mainly specializes in offering internet search services, but, recently, it has expanded its business to the mobile phone market and software industry (Weber 2008, 2). Many researchers have classified Google as among the most successful companies in the world, based on its market share and growth (Weber 2008, 2). Most of this success stems from the company’s positive corporate culture. An existing positive culture has set the tone for most of the company’s human resource practices. For example, the benefits that most of the company’s employees enjoy stem from this positive corporate culture. For example, free meals and free employee parties are common characteristics of the company’s human resource package for its employees (Weber 2008, 2).

Financial bonuses, open presentations by the company’s management are also other corporate practices that most of the company’s employees enjoy. These policies have created a culture of transparency, appreciation, and honesty, which has characterized interactions between the company’s management and its employees (Weber 2008, 2-4). This culture is not only synonymous with the company’s headquarters, but also its satellite offices in America and other regional headquarters around the world (Weber 2008, 2-4). Different departments within the company also have the same culture. Observers have commended the excellence of the company’s culture across its different branches because it is difficult to maintain a uniform culture in a large organization that is expanding (Weber 2008, 7).

However, the company has done so successfully. Other organizations that have shown the power of creating a strong corporate culture are Coca Cola and Apple. They have positively used corporate cultures to boost organizational productivity.

Based on the above case studies, we find that cultural principles and values serve the function of defining an organization’s performance. These values determine people’s behaviors and mindsets, which are important in realizing an organization’s vision, or meeting its goals (McCarthy 2012, 71-73). There is no generic measure for assessing an organization’s value. Each organization has its unique set of values that all employees use to guide them on how they should perform their functions (Janićijević 2013, 35-37). Different companies have competing values. For example, McKinsey Company (a global management consulting company) has a unique set of values that guide its employees in customer service. Google also has a similar set of values that prevail throughout all aspects of its corporate performance (its most common value is “do not be evil”).

Although many corporate values revolve around a few tenets of organizational performance, their originality is less important than their authenticity because the latter determines their effectiveness and purpose in organizations. Organizational values perform the motor functions of organizational culture. They determine how far organizations could go, or how much work employees are willing to do to improve their productivity (Janićijević 2013, 35-37). Simply, the values determine how far leaders could motivate employees to carry out their functions well.

Comparative Analysis of Biotensegrity and Organizational Culture

This paper has shown that organizational culture affects different aspects of organizational performance. This relationship stems from its influence on organizational structures. Researchers have investigated the mechanism through which culture affects performance, and vice versa, through the biotensegrity model, which resembles different aspects of organizational culture and its holistic effects on the overall organizational performance (Simitch and Warke 2014, 65).

To understand how we could apply the biotensegrity model to organizational culture, it is pertinent to compare and contrast the tensegrity structure to organizational culture. This section of the paper highlights different elements of the biotensegrity structure and their potential similarities to different elements of organizational culture. The purpose of doing so is to answer the first research question, which strives to find out how the biotensegrity model could explain organizational culture. Indeed, this section of the report shows how different parts of the tensegrity model represent unique aspects of organizational culture.

Flexibility

This paper has shown that one feature of the biotensegirty structure is flexibility (Simitch and Warke 2014, 34). The spine is a common biotensegirty structure that demonstrates this attribute. Its flexibility allows it to accommodate forces that press down on it, rotate it, or turn it upside down (Swanson 2013, 37-38). So long as the tension membranes are intact, the spine’s flexibility prevents different vertebrae from crushing on each other (Swanson 2013, 34).

The anatomy and physiological function of the reciprocal tension membrane outlines the function of organizational culture as the framework for understanding organizational functions. Simitch and Warke (2014, 67-70) say the reciprocal tension membrane is present in most living organisms. At a cellular level, it acts as a “reciprocal biomechanical cohesion” unit. For example, in embryos, it acts as a living and breathing tissue that connects different cells (Swanson 2013, 34). Its chief function is to provide a design for cell growth functions. Stated differently, it contains, restrains, and guides growth functions of a cell.

At an organizational level, a company’s workflow structure and culture also carry out the same functions, stated above, because different organizational functions contain, guide, and restrain growth functions in the organization. Comparatively, the reciprocal tension membrane oversees the manifestation and growth of different tissues (Simitch and Warke 2014, 66). Biodynamic forces guide this process because tissue formation outlines different tissue formation fields (across different metabolic fields). For example, tissue formation processes are different across different body structures, such as the bones, membranes and muscles. The development of these tissues follows natural physiological laws and principles of flexibility.

Flexibility is a common property shared by both the tensegrity structure and organizational culture. For example, market structures have shown that the failure of organizations to adapt to changes in their internal and external environments could lead to their collapse. Fairholm (1993, 27-30) delves into this argument by highlighting the important role of flexibility in leadership. However, he directs his arguments towards explaining the role of trust in supporting flexibility in different organizations. He says trust could help them meet different organizational needs (Fairholm 1993, 95-96).

The distinguishing feature of Fairholm’s (1993, 95-96) works is the emphasis he lays on harmonious and unified cultures. He also expresses his concerns about the continued attempts by different researchers to encourage the balkanization of value systems in different organizations. Instead, he proposes that different organizations should view organizational values as unique and innovative systems of organizational performance (Fairholm 1993, 75-76). In this regard, he says, “there is little hope that the acceptance of multiple and diverse internally competing values systems would produce stable, effective, responsive, economical, social or government institutions” (Fairholm 1993, 1).

People who support the concept of cultural relativism argue that no culture is better than another is (Janićijević 2013, 35-37). The product of this reasoning is the acceptance of varied and diverse value systems, or behaviors, that characterize different organizations. Some researchers have a problem with this view because they say cultural relativists encourage mediocrity in organizational culture (Schein 2010, 177).

They also say diversity often encourages mediocrity in leadership and promotes a sense of anti-culture behavior (Schein 2010, 177-180). Their views show that the acceptance of varied cultures is a politically correct concept, but does not help to improve organizational productivity. This analysis is captured by the concept of contextual ambidexterity which not only looks at an organization’s ability to adapt to varied environmental factors, in the general business understanding, but also throughout the entire business unit (Schein 2010, 167).

Alignment within the business unit also refers to coherence among the activities of all business partners. Stated differently, they should be working together towards achieving the same goal. Nonetheless, there is little contention among most researchers about the flexible and dynamic nature of organizational culture. Biotensegrity structures also share this property.

This paper has also shown that the biotensegirty structure is an efficient model (Judge 1984, 1-3). Most organizational structures also strive to achieve the same efficiency by minimizing wastages and maximizing the potential of their key competencies. The concept of ambidexterity highlights this fact because it highlights a conflict between alignment and efficiency in organizational leadership structures (Schein 2010, 198). Albert (2006, 395) sees this conflict as easy to solve by implementing dual structures. The dual structures would comprise of one group tackling alignment problems and another group tackling problems of adaptability.

Proper Communication

After reviewing the works of Schein (2010, 177) and Albert (2006, 395), we find that leadership structures affect organizational culture by mediating organizational behaviors. Indeed, leaders often choose to positively, or negatively, sanction certain organizational behaviors, depending on whether they align with their organizational vision, or not (Albert 2006, 395). Often, these behaviors become part of an organization’s culture. The role of leadership is much more profound in this respect because it allows for communication and collaboration in an organization (Singh 2011, 55). Expectations and power relations are other attributes that are subject to the behaviors of leaders because they eventually become part of organizational structures.

Inconsistencies in leadership and management represent manifestations in inconsistencies of organizational culture because cultural problems also arise in the same way as problems in the cranial system (Chivers 2006, 44-45). For example, an organization’s leadership is the “eyes” of the organization and from them; management sets the tone of the organization’s process (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2547).

Managers dictate the types of information that flows to other tenets of the organization, including the corporate strategy, management strategy, and HR plans. Therefore, here, we affirm that malfunctions in leadership, or management, could lead to poor information relays to other parts of the organization. The interconnectedness of different parts of the tensegrity structure demonstrates this fact. Organizational culture plays a similar critical function to an organization’s processes because it has a symbolic and cognitive effect on employee behavior. If there were a problem with the leadership, the cognitive function of culture would similarly suffer. The table below shows a broader understanding of the different organizational facets that make up an organization’s cultural framework.

The different facets of organizational culture mentioned above are comparable to the different functions of the biotensegrity system, or their biological functions.

Based on classic examples of leadership failures, such as the Enron scandal, the main leadership challenge that emerges in this study is the possibility of contradiction, turbulences, and insecurities that are often synonymous with management. Rationality, flexibility, and decisiveness are some qualities that exceptional leaders often exercise to overcome some of these challenges (Albert 2006, 395). Many of the research studies reviewed in this paper also reinforce the same view because they affirm the importance of leaders managing complex and dynamic processes (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2547; Dashwood 2012, 271).

However, several questions remain unanswered in this analysis. For example, we could question how leadership structures improve the capacity of present leaders to carry out their functions effectively. Similarly, we could question how robust theoretical constructs explain exceptional leadership qualities. However, based on the high number of theories that explain different aspects of leadership, such as motivation and competencies, it should not be difficult to answer these research questions.

Self-Regenerative and Self-Regulative

Extensive literatures, highlighted in this paper, have shown that the biotensegrity structure is a self-regulating model (Singh and Ananthanarayanan 2013, 115). The same attribute manifests in the organizational structure because it has a self-regulating function (Schein 2010, 178). This attribute stems from the fact that different cultures have boundaries, which guide employee activities. The relationship between the tensegrity system and organizational culture stems from the understanding of osteopathy, which presupposes that the human body is a self-renewing, self-regenerating, and self-recuperating model, which maintains a healthy system for supporting life (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541).

Therefore, whenever there is a breach in the functioning of the system, people develop diseases, or manifest symptoms of poor health (Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541). Organizational culture also has the same attribute because it self-generates and self-renews, depending on the organizational design and employee expectations and attitudes (O’Donnell and Boyle 2008, 5). This understanding explains why new employees in an organization are bound to adopt the same attitudes and behaviors of other employees in the workplace. These attitudes and behaviors are products of organizational culture.

In this regard, organizational culture is a biotensegrity model because it combines the attributes of flexibility, resilience, and strength (which are common characteristics of the biotensegrity model). The manifestation of these attributes also explains why many people have trouble changing organizational cultures in a short time. The resilience and strength of such cultures often lead to the resistance that most managers experience when trying to change organizational culture. The presence of different components of organizational culture working together in compression explains employee behaviors and attitudes that led to such outcomes.

Sometimes, these components do not directly relate to one another, but influence the wider understanding of organizational culture. Biological structures, such as the cranial system, also demonstrate the same qualities because they are products of rigid and elastic cell membranes. However, the unification of tensioned and compressed parts strengthens such structures. The muscles, bones, tendons and ligaments of the human biological system demonstrate these attributes.

Using a different analytical lens, we find that organizational culture is regenerative because it affects employee behavior and despite their location, or position, in an organization, they are always bound to act the same way. An understanding of culture as a socialization process best explains this fact because when groups develop unique cultures, they often pass down the same properties to new people, or members of the group. Schein (2010, 177) says studying the elements of culture, which older members of an organization pass down to new members, is an important part of understanding the elements of an organization’s culture. Nonetheless, doing so would only help a person to understand the abstract elements of the culture because, ordinarily, older employees do not tell new employees everything about a company’s culture, when they are newcomers (Schein 2010, 177).

Instead, new employees can only learn such information when they become part of a group’s inner circle, or acquire a permanent status in an organization (Cameron and Quinn 2011, 33). Here, the methodologies of socialization may reveal deep assumptions about organizational culture. To understand some of these assumptions and beliefs, it is crucial to understand the beliefs and value systems that guide organizations when they are in crisis. However, this analysis makes us question whether new employees could learn these assumptions through anticipatory socialization, or self-socialization. The latter understanding makes us also question whether new employees could discover the deep tenets of an organization’s culture by themselves, or not.

Many researchers have demonstrated that understanding the norms and assumptions of a company is the first task many new employees have to undertake when they come to a new organization (Fairholm 1993, 75-76). The success of this process mainly depends on the kind of feedback old members give new members of the organization. Therefore, a teaching process often occurs among new and old members.

Schein (2010, 19) says that the teaching process is usually unsystematic and disorganized. This process shows that culture is a tool for social control and can shape the perceptions of new employees, through the actions of old employees on new employees. In reference to this attribute, Schein (2010, 156) says when there are no shared assumptions between new and old employees; their interaction will be a product of creative communication.

However, the presence of shared assumptions would affirm the regenerative theory because culture would survive through teachings. While some studies disagree with the view of culture as a tool for social control (Williams 2002; Cameron and Quinn 2011, 34), there is little doubt that culture and most biotensegrity structures have a regenerative property because they can renew themselves. Indeed, studies by Burns, David and Christine 2008 (37) reveal that the effects of injury, or damage, to the biotensegrity structure could disappear naturally through a self-generative process.

For example, damaged tissues could heal, bones could become strong again, and nerves could regain their functionality when they suffer trauma. These inherent properties are characteristic of biological systems and organizational cultures. Culture acts as the main point of reference for most employees. The self-regeneration process often happens when leaders embed and transmit their values and beliefs through culture (Albert 2006, 395). For example, through this process, a leader could teach his subjects about his assumptions of team values and expect them to demonstrate the same properties in their behaviors. For example, if a manager does not respect organizational policies, or values, the same problem is likely to reflect in other groups of employees (Albert 2006, 395; Scarr 2008, 80).

Stability

A review of existing literature on the nature of the biotensegrity structure has shown that it is stable, despite the multiple forces that act on it (Singh and Ananthanarayanan 2013, 64; Judge 1984, 2-5). Organizational culture also shares the same attribute because all systems often strive to maintain equilibrium (Albert 2006, 395). According to Schein (2010), “Culture implies some level of structural stability in the group.

When we say that something is “cultural,” we imply that it is not only shared, but also stable, because it defines the group” (35). Group identity is the fulcrum of cultural stability because once people acquire the same values and principles; it is difficult to give them up easily. Their resistance creates the stability seen in organizational cultures because even if people leave an organization, the culture remains. Furthermore, it is difficult to get rid of culture because people value stability and prefer to work in a predictable environment that gives them meaning (Judge 1984, 1-3).

Coping, growth, and survival are key characteristics of organizational culture that help to maintain this stability (Judge 1984, 3-5). Different organizations also maintain their integrity and autonomy through the evolution of systems within the culture. Organizations that have this trait often differentiate themselves from others by acquiring a unique identity (Schein 2010, 36). Organizational culture is also deep, in the sense that it defines the conscious of a group of people. To some researchers, its intangibility and invisibility demonstrates its stability and importance to organizational functions (Singh and Ananthanarayanan 2013, 77; Schein 2010, 76).

Some biotensegrity structures also have the same depth (Singh and Ananthanarayanan 2013, 77). For example, the spine is an invisible structure of the human body, but plays a significant role in a person’s physical stability.

The anatomy of the human spine is comprised of 24 small bones held together by tiny ligaments (Scarr 2012, 54). These small bones are stacked up against each other. Between them are soft, gel-like cushions (discs) that act as shock absorbers, which prevent the bones from rubbing against each other. Tendons also fasten muscles to the vertebrae as facet joints link different vertebrae together. This structure gives them room to move against each other. Without the spine, human mobility would not happen easily and people would not be able to stand upright or even walk (Scarr 2012, 54). Organizational structure also plays the same stabilizing role because without it, organizations would not function properly. Besides supporting the body structure, the spine protects the spinal cord from damage or injury (Zhang and Ohsaki 2015, 6-8).

Similarly, organizational structures protect organizations from fraud, unethical business practices and such retrogressive behaviors. The stabilizing function of the spine is critical to the function of the human body because the spinal cord contains nerves that connect the human head with other parts of the body. This is why a problem with the head manifests in the body and similarly, a problem with the body manifests in the head.

The same is true for organizational structures because a problem with management would manifest in employees and a problem with the employees would manifest in management. Therefore, bodily movements are a function of nerve efficiency between the brain and human limbs. Similarly, organ functions are a product of effective nerve functions. This is why doctors often recommend that having a healthy spine is a prerequisite for a healthy and active lifestyle (Zhang and Ohsaki 2015, 6-8).

Concisely, biotensegrity structures demonstrate the same qualities of stability (Singh and Ananthanarayanan 2013, 23). A deeper analysis of this quality shows that super stability and pretest stability characterize such structures. Super stability emerges when there are positive semi-definite quadratic forms of configurations that underlie the tensegrity structure (Scarr 2012, 54). If we extrapolate their application to the Dynamic Shifting of Tensions in the Dura Mater, according to the Sutherland model of the cranial system, we find that the dynamic shifting of tensions in the Dura Mater also highlights the tensile forces that characterize biotensegrity and account for its stability (Burns, David and Christine 2008, 8-10).

These tensile forces come from meninges, which exert a tensile force around the brain and the spinal cord (Theodore 2009, 100). The forces of tension in the Dura Mater explain why Sutherland referred to it as the “reciprocal tension membrane” (Scarr 2012, 54). A pull from one side of the membrane is likely to cause a similar pull on another side of the membrane. The structural integrity of the bony cranium is a product of these tensile forces (Burns, David and Christine 2008, 9). A trauma to the head is likely to affect the stability of the dural membranes by destabilizing the fulcrum around which the rhythmic movements in the dural membrane are organized (Scarr 2012, 54).

Schein (2004, 175) says that social structures in an organization create stability, the same way biotensegrity does. For example, tensegrity forces that would accommodate them in an organization’s culture could mitigate conservative and progressive forces in an organization. A value system would mitigate the massive strain that both forces would have on an organization’s structure. Fairness and reconciliation of interests are potential products of this value system (Schein 2010, 176).

Besides their stabilizing effect, organizational cultures set the stage for biotensegrity structures to thrive in an organization. Therefore, it would not make sense, for example, to talk about autonomy if power structures do not allow leaders to be in touch with their true selves. If we use a different example, we find that the process of reconciling warring factions of people within one culture would fail if managers, or leaders, do not find areas of commonality between the two parties. Similarly, if the environment in the organization encourages stiff competition among different parties, there would be minimal chance of reconciliation (Schein 2010, 166). Therefore, tensegrity helps to blend the different forces of organization culture to create a coherent system of employee performance.

Patterning or Integration

This paper has demonstrated that the cranial system and other biotensegrity structures have a wide breadth of functions, especially concerning the sensory functions of the body (Judge 1984, 4-7). Organizational culture also shares the same characteristic because once leaders entrench a specific type of culture in an organization; it covers, most, if not all, aspects of an organization’s functions (Judge 1984, 7-8).

Most of the articles sampled in this paper have alluded to this fact by saying that culture is pervasive (O’Donnell and Boyle 2008, 4; Sims and Quatro 2015, 253-254). Therefore, when we refer to an organization’s culture, we mean a definition of its operations and interactions, in lieu of the different aspects of its internal and external environment. This definition alludes to the existence of a larger paradigm of integration that ties together different aspects of an organization’s processes. For example, it ties together rituals, values and behaviors of different cadres of employees in an organization (Judge 1984, 5-8).

This integration stems from the human need to make the environment orderly and predictable (Schein 2010, 177). Naturally, a disorderly environment, or a senseless environment, would make many leaders and their subjects feel anxious. However, through progressive organizational cultures, they would strive to minimize this effect by creating and appreciating a common set of values and beliefs (Schein 2010, 121). Although this argument appears straightforward, it makes us ask, what is the true “essence” of culture? The best way to understand its application and relevance in leadership and organizational processes is by comparing it to the principle of evolution, which other researchers have used to explain biological structures (especially, the concept of adaptation) because if we think of culture this way, we can understand its abstract nature.

The pulse that culture sets in an organization is only comparable to the fluctuations of the cerebrospinal fluid, which is a core component of the primary respiratory mechanism (according to Sutherland’s model) (Scarr 2012, 54).

The movements fluctuate rhythmically around the brain and spinal cord, through the cerebrospinal fluid (Hendryx 2014, 10). Some research studies have proved that this movement is observable and changeable through a tap of the spine (Burns, David and Christine 2008, 23). Indeed, numerous research studies have documented this fact (Cummings 1994, 9; Hendryx 2014, 10; Ingber and Levin 2007, 2541). Albeit controversial, experts in the field of neurosurgery support this observation (Hendryx 2014, 10). Some researchers have referred to the potency of the cerebrospinal fluid as the “liquid light” (Burns, David and Christine 2008, 23). Its volatility and property exemplifies the similarity of the cranial system to organizational culture because it creates a pulse that sets the tone throughout the system. Culture also sets the tone and pulse of organizational systems.

Problem Assessment Mechanism

Problems with organizational culture are often difficult to understand. Consequently, it is common for managers to diagnose organizational problems, wrongly, based on their failure to understanding organizational cultures. In this regard, they may change organizational structures, or address irrelevant issues regarding organizational performance, when they are supposed to address cultural issues. The following case study demonstrates this common problem

In the early 2000s, a medical company called Aetna was struggling to maintain a positive reputation among customers and its stakeholders, despite posting good profits. Increased cases of lawsuits from physicians and customers who complained about the company’s poorly managed care performance was the cause of the problem (Katzenbach and Kronley 2012, 9). Experts estimated that at the height of the problem, the company was losing more than $1 million daily in increased overheads, court settlements and unsuccessful business acquisitions (Katzenbach and Kronley 2012, 7-10).

They traced most of the company’s problems in a retrogressive company culture, which was more than 100 years old (Katzenbach and Kronley 2012, 11-13). The prevailing company culture encouraged many employees to be risk-averse and steadfast. These qualities encouraged employees to take unnecessary risks to get their work done. It also made them arrogant in how they undertook their jobs because they knew they were the “best” in the industry. Similarly, the culture encouraged a strong “brotherhood” movement among employees that made them suspicious of outsiders. It also encouraged them to cover up for each other, even if they made mistakes in the workplace. The demerits of this culture emerged in mid 1996 when the company entered into a joint venture with a lower-placed medical agency, US Healthcare (Katzenbach and Kronley 2012, 9-11).

US healthcare had a different culture from Aetna because its employees were aggressive and more disciplined than their counterparts were. Furthermore, Aetna’s employees were conservative. Therefore, there was a cultural clash. Instead of finding a compromise between the two cultural extremes, Aetna’s culture became more intransigent. Aetna’s Board of Directors tasked its managers with the responsibility of changing this culture, but most of them failed and subsequently left the organization (Katzenbach and Kronley 2012, 7-10).

The managers failed to realize that its corporate culture was uniquely appealing to the organization and they could not exchange it with another party, as would be the case when one sells a parcel of land or a used car. Indeed, for all its faults and successes, the company’s corporate culture was uniquely appealing to the organization’s employees and not new ones. Sims and Quatro (2015, 253-254) say that although companies may experience difficulties changing their organizational cultures, it is incumbent on them to draw on the positive aspects of culture and use them to a merger’s advantage. Similarly, it helps organizations to avoid the negative pitfalls that are associated with mergers and acquisitions (Sims and Quatro 2015, 253-254). This approach makes it easier for managers to cope with change by merging different corporate cultures.

Five years after merging with US Healthcare, Aetna was still experiencing operational problems that stemmed from a cultural clash between the old and new employees. A new CEO, John Rowe, joined the company in the late 2000s to steer its operations (Katzenbach and Kronley 2012, 11-15). Most of the employees thought he would suffer the same fate as his predecessors because they had seen four different management changes in five years (Katzenbach and Kronley 2012, 14-17).

However, Rowe came with a different corporate strategy, which focused on collecting the views of the employees and investigating their operational challenges, as opposed to trying to merge the corporate cultures of the two sets of employees, as the other managers did. This strategy prompted him to interview some of the most respected employees. He also interviewed those who were sensitive to the company culture to get their views of the company’s problems.

The employees provided him with invaluable knowledge regarding how they should design and execute their corporate strategy. Through small changes in the company’s operational strategy, he was able to instill a new set of behaviors among employees, which later grew to become the organization’s new corporate culture. The managers called it “the New Aetna” (Katzenbach and Kronley 2012, 14-16). Without describing his efforts as cultural change, the manager solved the company’s perennial problem of cultural clash.

This case study demonstrates two issues. First, it shows the strong impact of cultural influences on organizational processes because Aetna was unable to function well when the company was suffering from an organizational culture problem. Indeed, this case study demonstrated how permissive cultural issues could be in an organization because the problem affected all cadres of employees. Furthermore, the cultural clash affected most aspects of organizational processes. The second issue that emerges from this case study is the potential negative effects that organizations could suffer if they ignore cultural issues. Concisely, the case study shows the interconnected nature of cultural issues because it had to take the intervention of the top echelons of the organization to address/manage a problem that mostly affected lower-level employees.

The biotensegrity model and organizational culture share similar approaches to problem diagnosis because they both adopt a bottom-up approach. For example, doctors assess cranial problems using a bottom-up approach and researchers recommend the same approach when diagnosing organizational problems (Albert 2006, 395). A wrong diagnosis of cranial problems would lead to a wrong solution. Similarly, as demonstrated by the Aetna Case study, a wrong diagnosis of cultural issues would lead to a wrong understanding of organizational problems and solutions.

The relationship between the processes of assessing problems in the cranial system and in organizational structures also stretches to Cummings’s (1994, 9) understanding of the craniosacral manipulative therapy, which is a therapeutic approach for solving cranial problems. Its effects on helping patients to move cranial bones are consistent with past studies of osteopathy in the cranial field (Scarr 2008, 13).

In fact, Cummings (1994, 9-12) says that this consistency in findings makes him believe that William Sutherland envisioned the system in his past teachings. Indeed, through his explanation of transmutation of cerebrospinal fluid, Sutherland said that when the system interacts with different components of the cranial system, it becomes bigger than the sum of its parts (Hendryx 2014, 10). By using terms like “transmutation,” Sutherland’s model falls short of presenting the cranial system as a mechanical model. Instead, it creates more emphasis on presenting the model as an interactive system for supporting biological functions.

Stated differently, the cultural systems in organizations, which affect employee behaviors, attitudes and managerial conduct, share common characteristics with the same systems that define the biological functions in the cranial system. This section of the paper affirms this fact because it demonstrates the similarities in inputs, associated reflexes, and outputs between the cranial system and the organizational system. For example, Chivers (2006, 45), says, in the cranial system, if a person has spinal or pelvic dysfunction, the outcome would manifest as a dysfunction in the cranial nerves.

The application of the tensegrity model in understanding the interconnectedness of the cranial system may emerge as a unifying theory of assessing problems that do not only afflict the cranial system, but the wider musculoskeletal system as well (Scarr 2012, 16). The craniosacral therapy method for addressing cranial problems could bring change in the cranial system in ways that current professionals, who have studied the cranial field and systems, do not understand. Nonetheless, the hypothesis of the cranial system being a tensegrity structure (through its continuous tension network) is only one hypothesis of understanding the system. This analysis has also used the same framework (tensegrity) to explain organizational culture, based on the similarities in properties that both systems share. However, proponents of the tensegrity structure have struggled to make it a verifiable explanation for explaining processes in the clinical space.

Conclusion

At the start of this paper, we found out that most organizational problems are mere consequences of unquestioned axioms surrounding organizational cultural norms. They are also products of inherent assumptions of the same norms and values that have caused decades of perpetual unethical practices, such as greed and inefficiency in organizational processes. Today’s CEOs often ignore this thread of analysis as they dedicate most of their time trying to meet targets and please their shareholders. In this study, we have explored how different researchers, scholars, and academicians have explored the concept of tensegrity and related it with different scientific fields, such as biology (orthopedics) and architecture. There have been no concrete attempts by these groups of professionals to explore cultural dynamics using the tensegrity (biotensegrity model).

To fill this research gap, we have used the works of some researchers, such as William Sutherland, who is among the world’s most respected osteopathic physicians, to answer the research questions. His contributions to the understanding of the biotensegrity structure stem from his contributions in understanding the cranial system because he was among the first researchers to conceptualize the system and teach it systematically to his peers. For example, he was among the first people to affirm a rhythmic shape change in the cranial bones. Researchers have also used his works to understand movements across body tissues, as a strategy of explaining how to correct dysfunctional tissues. In this paper, we have conceptualized this system as the “primary respiration system.”

This paper has also emphasized the importance of understanding organizational structures as influencers of organizational culture because they affect leadership. Here, leadership structures draw our attention towards identifying the most important action centers in organizations. In the context of this study, the most important action center is the leadership of an organization. Therefore, it is important to look at structures that moderate the interaction occurring at the top echelons of leadership.

This paper shows that it is not important to look for organizational structures that have a definite and unalterable social structure because they rarely exist and would not complement our understanding of biotensegrity in organizational cultures. Instead, it proposes the importance of having structures that have incoherent and unpredictable formats. Although they may create contradictions and conflict in the organization, they stimulate tensions that provide a healthy balance of forces in the organizational structure (biotensegrity). This bolsters the potential for self-generation and progress.

In this study, we have investigated the type of structural factors that could accommodate these forces. To come up with the relationship between the biotensegirty structure and organizational culture, we have also explored the kind of structures that could produce the desired behaviors through positive leadership. Consequently, we have come up with the biotensegrity model/structure. Concisely, through organizational cultures, leadership assumes the tensegrity model by stimulating dynamic and conflicting forces on one hand and providing organizational stability in another.

Although this analysis is straightforward, it is important to understand that organizational structures cannot influence behavior in their absolute nature. However, they may do so by suppressing undesirable behaviors and supporting positive behaviors. Usually, people are unaware of this influence on their actions, or behaviors. However, their ignorance does not demean the fact that the biotensegirty structure of leadership is an “action generator.”

This statement shows the important role played by programs in organizational behavior. In this regard, such programs are not merely tools, or prescriptions of organizational processes. Instead, they influence people’s perceptions, values and beliefs. In this regard, organizational structures (which draw a strong comparison to biotensegrity structures) influence organizational thinking. However, compared to organizational programs, structures are less rigid and give employees more flexibility in undertaking their functions.

Comprehensively, the research findings in this paper reveal that the biotensegrity model could explain organizational culture. They also show that the similarity between the biotensegrity model and organizational culture stems from the similarities in characteristics that both systems share. These characteristics are stability, regeneration, flexibility, and patterning. This paper also demonstrates that both systems have similar problem diagnosis procedures. It has also taken a closer look at organizational culture and explained the need for looking into it despite the uncertain external and internal organizational factors that affect organizational operations. The findings of this paper infer that most organizations experience cultural problems because of ineffective organizational designs and systems.

Understanding the application of the biotensegrity model to organizational culture could help managers and employees get the “bigger picture” surrounding their organizational roles and their input in realizing organizational performance. This paper has suggested a close relationship with this analogy by linking the “big picture” of poor organizational cultures with employee performance.

For example, the performance of an organization could be affected by the communication structure (time taken for information to move through different cadres of employees), changes in technology, political circumstances and organizational cultures. Similarly, a narrow span of organizational control may limit individual expression, thereby affecting motivation levels and enthusiasm for employees to undertake their roles because they would not understand the larger role they play in the organization. The potential use of a biotensegrity model to explain organizational culture could help to provide this perspective. From this background, this paper argues that the biotensegrity model could explain organizational culture. It also shows that the similarity between the biotensegrity model and organizational culture stems from the similarities in characteristics between the two.

References

Albert, Martin. 2006. “Dialectical conditions: Leadership structures as productive action generators.” Management Review 17, no. 4: 395-419. Web.

Burns, Denise, David Fuller, and Christine Lerma. 2008. “A Comparison of Swedenborg’s and Sutherland’s Descriptions of Brain, Dural Membrane and Cranial Bone Motion.” American Academy of Osteopathy 18, no. 2: 1-38. Web.

Cameron, Kim, and Robert Quinn. 2011, Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons. Web.

Chivers, Maria. 2006. Dyslexia and Alternative Therapies. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Web.

Cummings, Charles. 1994. “The Tensegrity Model of Osteopathy in the Cranial Field.” Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 94, no. 12: 9-27. Web.

Dashwood, Hevina. 2012. The Rise of Global Corporate Social Responsibility: Mining and the Spread of Global Norms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Web.

Fairholm, Gilbert. 1993. Leadership: And the Culture of Trust. Westport, IR: Praeger. Web.

Hendryx, Jan. 2014.”The Bioenergetic Model in Osteopathic Diagnosis and Treatment: An FAAO Thesis.” The American Academy of Osteopathy Journal 24, no. 2: 10-18. Web.

Ingber, Donald. 1998. “The Architecture of Life.” Scientific American 278, no. 1: 48-57. Web.

Ingber, Donald, Steven Heidemann, Philip Lamoureux, and Robert Buxbaum. 2000. “Opposing views on tensegrity as a structural framework for understanding cell mechanics.” Journal of Applied Physiology 89, no. 4: 1663-1678. Web.

Ingber, Donald, and Michael Levin. 2007. “What lies at the interface of regenerative medicine and developmental biology.” Development 134, no. 1: 2541-2547. Web.

Janićijević, Nebosja. 2013. “The Mutual Impact of Organizational Culture and Structure.” Economic Annals 58, no. 198: 35-60. Web.

Johnson, Craig. 2003. “Enron’s Ethical Collapse: Lessons for Leadership Educators.” Journal of Leadership Education 2, no. 1: 45-56. Web.

Judge, Anthony. 1984. From Networking to Tensegrity Organization. Washington, DC: Union of International Associations. Web.

Katzenbach, Jon, and Caroline Kronley. 2012. “Cultural Change That Sticks.” Havard Business School. Web.

Kortmann, Sebastian. 2012. The Relationship between Organizational Structure and Organizational Ambidexterity: A Comparison between Manufacturing and Service Firms. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media. Web.

Kosciejew, Richard. 2012. The Designing Theory Of Transference. New York, NY: Author House. Web.

Kusluvan, Salih. 2003. Managing Employee Attitudes and Behaviors in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry. New York, NY: Nova Publishers. Web.

McCarthy, Quinn. 2012. Police Leadership: A Primer for the Individual and the Organization. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Web.

Motro, Rene. 2003. Tensegrity: Structural Systems for the Future. London, UK: Elsevier. Web.

O’Donnell, Orla, and Richard Boyle. 2008. Understanding and Managing Organisational Culture. Dublin, IR: Institute of Public Administration. Web.

Patterson, Mic. 2011. Structural Glass Facades and Enclosures. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons. Web.

Scarr, Graham. 2008. “A model of the cranial vault as a tensegrity structure, and its significance to normal and abnormal cranial development.” International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine 11, no. 3 80-89. Web.

Scarr, Graham. 2012. “A consideration of the elbow as a tensegrity structure.” International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine 15, no. 2: 53-65. Web.

Schein, Edgar. 2010. Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Web.

Simitch, Andrea, and Val Warke. 2014. The Language of Architecture: 26 Principles Every Architect Should Know. New York, NY: Rockport Publishers. Web.

Sims, Ronald, and Scott Quatro. 2015. Leadership: Succeeding in the Private, Public, and Not-for-profit Sectors. New York, NY: M.E. Sharpe. Web.