Introduction

Background

A referendum slated for June 2016 would determine whether the United Kingdom (UK) would stay, or exit, the EU. British economic experts have often debated the need for the country to stay in the European Union (EU), or exit the economic bloc (Charter 2012; House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008). Different arguments have shaped this debate, as some contend that leaving the EU would have many negative consequences on Britain’s ability to sell its goods, while others believe that its exit could have many positive effects on the country’s economy (MacShane 2015; BBC 2016).

People who advocate for the exit of the UK from the EU say many countries have successfully negotiated different trading agreements with EU member nations without necessarily being part of the bloc (Centre for European Reform 2014). They have cited the Turkish model, the Norwegian model, and the Swiss model as examples of how independent nations could successfully trade with EU countries without necessarily being part of the association (Minford et al. 2015).

People who have an opposing view believe that an “amicable divorce” between the EU and the UK is not feasible, as member countries would not allow the latter to choose the laws and regulations that favor it and dismiss those that do not (Tournier-Sol & Gifford 2015). They also say that the UK could take many years to negotiate new trade agreements with independent nations – a process that could take a long time (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008). The biggest fear is a trade war between the UK and EU member states.

Statement of the Problem

Arguments about the potential exit of the UK from the EU have touched on the labor market, as there are several competing claims about how many jobs the UK could lose, or gain, if the country exits, or stays in the EU (Sloane, Latreille, & O’Leary 2013; Hothi 2005). Coming up with precise figures to clarify this argument is difficult because it is still unknown whether foreign companies that operate in the UK would make their threats real by exiting the market (Centre for European Reform 2014). Experts also do not know how many jobs could be lost, or gained, through a reshaping of the UK economy by exiting the EU (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008). This paper proposes a study to explain this research gap by investigating the effects of the UK’s potential exit from the EU on its labor market.

Research Aim

Investigating the Effect of UK’s potential exit from the EU on its labor market.

Research Objectives

The objectives for achieving the above research aim are:

- To find out if there would be job losses arising from the UK’s exit from the EU.

- To investigate the impact of the UK’s potential exit from the EU on the country’s migrant population.

- To explain the impact of the UK’s potential exit from the EU on the country’s unemployment rate.

The following questions are instrumental in the attainment of the above research objectives

Research Questions

- Would there be job losses because of the UK’s exit from the EU?

- What is the impact of the UK’s potential exit from the EU on the country’s migrant population?

- What is the impact of the UK’s potential exit from the EU on the country’s unemployment rate?

Rationale for the Study

Understanding the impact of a potential exit of the UK from the EU economic bloc could explain the future of the country’s labor market (Badinger & Nitsch 2015). For example, the UK’s exit from the EU could explain the country’s future policy on immigration, future policies on bookkeeping, and predict the direction that the skilled manufacturing sector would follow. An analysis of this research issue could also help to predict patterns of demand for skills and forecast shifts in labor movements across different skill sets.

Proposed Research Structure

- Introduction

- Background

- Statement of the Problem

- Research Aim

- Research Objectives

- Research Questions

- Rationale of Study

- Literature review

- Methodology

- Philosophical Approaches

- Research Strategy

- Sampling Strategy

- Data Analysis

- Ethical Issues

- Reliability and Validity Issues

- Findings

- Discussion and Analysis

- Conclusion

Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter reviews existing literature concerning the UK labor market and the effects of a potential exit of the UK from the EU economic bloc. It also includes a review of theories and models of trade and their impact on the labor market. Collectively, this analysis would help us to come up with themes, which we could use for future analysis of the research issue. The theoretical issue for understanding this analysis appears below

Theoretical Foundation

The international relations theory is an important conceptual framework for understanding the potential exit of the UK from the EU economic bloc because it could explain the relationship between the UK and the EU (Desch 2015; Mearsheimer & Walt 2013). Stated differently, it strives to provide different models for understanding how nations relate. Realism and liberalism are the main schools of thought in this conceptual framework (Forde 1995). Idealists have often argued that the need for a sense of collective security among nations could substitute the balance of power outlined in international relations (Desch 2015).

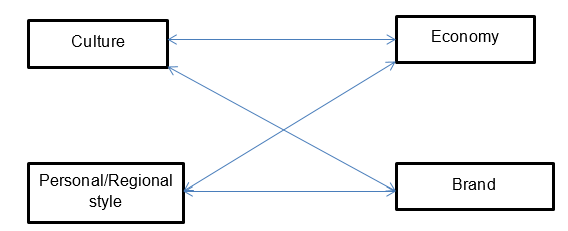

Liberalism holds that state preferences influence state actions more than the capabilities of a state do (Keohane 2009). This school of thought also recognizes the role played by non-state actors in influencing a government’s decision-making process (Mearsheimer 2001). Therefore, non-state factors, such as culture, economic systems and types of governments are likely to affect state actions and outcomes (Weber 2014; Copeland 1996).

If we extrapolate this conceptual framework to the context of our analysis, we find that the UK labor market could be influenced by high political factors, such as security issues and low political factors, such as societal attitudes towards the EU, immigrant patterns, and even the culture of the UK (Aggarwal 2010). Firms, corporations, individualities, and institutions could exercise these influences on the labor market and the British population (Sjoberg 2013).

Changes in the UK Labour Market

Recent studies of the UK labor market have pointed out that it has more than 32.7 million workers (CEBR 2013). Researchers have obtained this finding after evaluating the supply of labor from UK households and comparing it with the demand for workers by local firms (CEBR 2013). They have also used the same analysis to determine wage patterns in the labor market (Mearsheimer & Walt 2013). The wage rate is a common factor that affects the demand for labor in the UK market.

However, it is a function of the country’s labor policies. Indeed, a high number of migrant workers living in the country could have a downward pressure on the wage rate and a low number of immigrants could have an upward pressure on wages (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008). Union activity also has the same effect on wage rates (30% of the UK labor force are part of a union) because increased union activity could lead to an increase in wages and low levels of union activity could lead to low wage levels (Eldring 2008).

According to Badinger and Nitsch (2015), the UK labor market has witnessed significant changes in the past decade. For example, since the 1980s, there has been a significant decline in the dominance of the manufacturing sector (Centre for Economics and Business Research 2013). Consequently, there has been a decline in union activity because most of them are concentrated in the manufacturing sector (Chan 2016).

Comparatively, most of the jobs have moved to the service sector (Centre for European Reform 2014). The growing importance of the service sector in the country’s labor market has seen a growth in the number of women in the labor force and a similarly fast growth in the number of part-time jobs (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008). This trend has thrived on the back of the government’s recent efforts to liberalize labor policies, which have allowed EU members to seek employment in the UK (MacShane 2015; BBC 2016).

Globalization has also fanned this trend. Demographic changes have seen a rise in the percentage of old people in the labor market (Badinger & Nitsch 2015). Most researchers have pointed out the rise in dependency as the main product of this demographic shift because many UK employees have to take care of their aging relatives (MacShane 2015; BBC 2016). Some of these trends have created more jobs in the upper echelons of job hierarchy than the lower levels of management (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008). Changes in technology and advances in trade tools have been the main drivers of this change (MacShane 2015; BBC 2016).

Impact of EU Labour in the UK

Independent studies of the European labor market show that a potential UK exit from the EU economic bloc would limit the country’s growth and worsen its public finances (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008). A report from the Centre for Economics and Business Research (2013) supports this view by showing that UK’s exit from the EU could lead to a 2% loss in the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

By 2050, this loss would amount to £60 billion. The same report shows that government borrowing could increase if the UK leaves the EU because there would not be enough employees to replace the country’s aging population (MacShane 2015; BBC 2016). A recent report about the behaviors of migrant workers showed that most migrants from the EU are more likely to be at work than their UK counterparts do (CEBR 2013). The comparative percentages are 63.3% (for migrant workers) and 56.2% for UK citizens (MacShane 2015). This analysis means that EU migrants are more active than UK workers are.

Some researchers have disputed the notion that EU migrant workers exert a downward pressure on wages and unemployment in the UK (Eldring 2008). MacShane (2015) shares this view when it argues that the belief that most immigrants are taking away jobs from UK citizens is false, as they are helping to build the economy by paying taxes and buying goods and services. Furthermore, some immigrants bring skills and value to the UK labor market, thereby improving the quality and availability of labor in most industries.

Researchers who share similar views also believe that UK’s potential exit from the EU could negatively affect the country’s labor market because many skilled UK employees find work abroad (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008). Therefore, leaving the EU could expose them to social welfare problems. Employers would also fail to enjoy the flexibility that they have always enjoyed by having a free trade agreement with EU member states.

Relative to this view, MacShane (2015) says the exit of the UK from the EU could lead to fewer immigrants coming to the UK because the government would most likely tighten immigration control to prevent people from entering the UK. Although the exit would bring more freedom to the UK government to do as it pleases, a similar action by EU member nations who may be inclined to impose similar border restrictions on UK citizens if they want to enter the EU may negate their efforts.

Although different studies have reported mixed reviews about UK’s potential involvement with the EU, MacShane (2015) says the characteristics of migrants and differences in worker groups, in the UK labor market, could directly affect the country’s labor market if it exits from the EU. For example, different studies have reported different findings for different groups of immigrants (Minford et al. 2015). Most of them have explored the effects of Eastern European immigrants in the UK labor market and shown that most migrants who have lived in the UK for long are less likely to feel the effect of the exit, compared to immigrants who have lived in the UK for a short time (MacShane 2015).

Years of exposure to UK laws, attitudes and culture are likely to affect their perspectives. Nonetheless, research studies from the UK, United States (US), Canada, and Australia (among other countries that have significant migrant populations) show that migrants do not negatively influence the labor market (Tournier-Sol & Gifford 2015). In this regard, there is a disconnect between the rhetoric on immigration and the evidence surrounding it.

Law and Policy Issues

A potential exit of the UK from the EU economic bloc could have a potential impact on UK’s employment policy laws because the country would no longer be obligated to abide by EU employment laws (Isaac 2015). However, if it chooses to stay within the single market, but exclude itself from the economic zone, it would have to accept specific rules about EU employment laws and policies (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008). For example, such an agreement would directly affect the free movement of people, in and out of the UK (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008).

Miller (2016) weighs in on this issue by saying an exit from the EU could significantly the UK’s employment laws. The potential exit of the UK from the EU could affect some tenets of the UK law, such as annual leave and agency worker rights (Miller 2016). The Working Time Regulations 1998 is a key legislation in the UK labor market that would change from such a move (Barnard 2012). Miller (2016) believes that if the exit happens, employment groups are likely to pile pressure on the government to amend some of the EU-derived legislation that affect the labor market. Comparatively trade unions are likely to oppose attempts by these employment unions to reserve some of the gains that most workers have made from the UK joining the EU (House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008).

Proponents of the UK’s independence from the EU have cited the success of other European countries, which are not part of the bloc (Centre for European Reform 2014). For example, they have often touted the success of the Norwegian model as an example of the potential that the UK could enjoy if it leaves the EU (Centre for European Reform 2014). A common point of discussion is the relatively low unemployment rate that Norway enjoys despite not being a member of the EU (Chan 2016).

Nonetheless, the quest for the UK to leave the EU has often thrived under an active wave of “euro-skepticism” that has always characterized UK politics. Many studies have highlighted this issue through a survey of people’s opinions about EU membership (Centre for European Reform 2014). They have found that the UK has the lowest approval rating for being a member of the EU (Tournier-Sol & Gifford 2015). Latvia and Hungary also have similar dissenting views (Isaac 2015).

Summary

Most of the studies that have investigated the impact of the UK’s potential exit from the EU have only abstractly done so. For example, there is little information regarding the specifics of the UK’s exit from the EU on key indicators of the labor market such as unemployment and migration policies. The proposed study would seek to fill this research gap through a comprehensive review of the research issue.

Research Methodology

Philosophical Approach

There are many philosophical approaches available to use in the proposed research study. They include positivist, interpretive, and deductive techniques (Mantzavinos 2009). The key features of a positivist approach are relying on scientific approaches, objectivity, robustness, identification of causes, and the use of the methods of natural sciences (Seale 2004). Interpretivism also has unique features that mainly include social action because, in its application, the researcher’s role is to interpret social action (Blaikie 2007). The proposed study would use a combination of different philosophical approaches to investigate the research issue. They include

Phenomenological Approach/Interpretivism

The phenomenological approach is a study of people’s subjective meanings. This philosophy also assumes that external and internal factors that are not easily discernible shape people’s experiences and actions (Seale 2004). Therefore, this research philosophy is mostly a product of people’s subjective annotations to a research issue.

Critical Realism Approach

The critical realism approach strives to find the reasons behind different issues to come up with solutions (Sarantakos 2012). This research approach is analogous to the positivist research approach because it adopts a scientific understanding of research issues (Blaikie 2007). For example, business and management researchers who have used this research approach argue that today’s social structure is a product of our understanding of the same (Mantzavinos 2009).

Research Strategy

The proposed research would use a combination of both the qualitative and quantitative research approaches. The purpose of doing so is to get uninhibited research information (Hesse-Biber 2010). There are different types of strategies to use for collecting data under this research strategy. Some of the most common methods include surveys, interviews, and observations. The researcher would interview experts who have a proper understanding of the EU commercial space and the UK labor market. Additionally, the researcher would collect information from published sources (secondary research) to compare and contrast the information obtained from the interviews. The published sources will mainly include books and peer-reviewed journals.

Sampling Strategy

The proposed study would include the snowball sampling technique as the main research approach to the study. This non-probability sampling technique allows respondents to recruit new respondents through social networks (Bailey 2008). It is appropriate for this study because it is difficult to locate experts who are knowledgeable in the research field without referrals. The first respondent would be an acquaintance who runs a business consulting company in the UK. Through his networks, I intend to get contacts of other people who are knowledgeable about the research topic.

There would be no financial motivation to participate in the study. The interview would contain open-ended questions that strive to investigate the effects of the UK’s exit from the EU. The purpose of collecting data this way is to gather multiple views about the research issue. In this regard, we strive to have diverse information about the research issue. The interviews would be recorded using audiotapes.

Data Analysis

The data analysis process would be in two parts – qualitative data assessment and quantitative data assessment. The quantitative data analysis process involves the analysis of numerical data. It would involve the use of statistical techniques of data analysis, such as graphs, tables, and cross-tabulation of variables. The qualitative data assessment process would involve the analysis of non-numeric data.

To analyze this type of data, the researcher would use deductive reasoning. For example, after each interview, the researcher would carefully listen to the audiotape and transcribe the information contained in them. Thereafter he would clean, summarise, and categorize the data to come up with information that would attach meaning to different categories of the research topic. The thematic analysis of the research issue would follow the categorization of data into different research questions. The researcher would also triangulate the information obtained from both the qualitative and quantitative research approaches to come up with research findings that emerge from correlations among the research groups.

Ethical Issues

To ensure the ethical integrity of the proposed study, we would strive to meet several ethical principles of research outlined in Gregory (2003). The first one is confidentiality. During the interviews, the interviewer would guarantee the respondents that their identities and addresses would not appear in the study. The second issue would be informed consent. The interviewer would not coerce any respondent to participate in the study. Instead, the respondents would participate voluntarily after signing an informed consent form. The researcher would inform them of their right to withdraw from the research without any punitive actions imposed on them. The interview findings would be stored safely through encryption techniques and availed to the participants if they requested.

Reliability and Validity Issues

Validity refers to the ability of a research study to measure what it is supposed to measure (Baumgarten 2013). Content and construct validities are the main types of assessments in this regard (Baumgarten 2013). To safeguard the validity of the findings in the proposed study, the researcher would strengthen the validity of information obtained through the interview through a review of existing literature. Similarly, the researcher would do a review of the research tools to affirm their applicability and validity before employing them in the study.

The reliability of a study refers to its ability to produce similar findings when someone else repeats the study (Rubin & Babbie 2009). Studies that have a high-reliability index are often accurate, dependable and consistent (Rubin & Babbie 2009). To enhance the reliability of the research, pre-testing the study tools would be an integral part of their application. This step would enable the researcher to detect errors before using the research tools.

Time Plan (Gantt chart)

The Gantt chart below shows the approximate time for completing different stages of the proposed study

References

Aggarwal, V 2010, ‘I Do not Get No Respect: 1 The Travails of IPE2’, International Studies Quarterly, vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 893–895. Web.

Badinger, H, & Nitsch, V 2015, Routledge Handbook of the Economics of European Integration, Routledge, London. Web.

Bailey, K 2008, Methods of Social Research, Simon and Schuster, New York. Web.

Barnard, C 2012, EU Employment Law, OUP Oxford, Oxford. Web.

Baumgarten, M 2013, Paradigm Wars – Validity and Reliability in Qualitative Research, GRIN Verlag, London. Web.

BBC 2016, UK and the EU: Better off out or in?. Web.

Blaikie, N 2007, Approaches to Social Enquiry: Advancing Knowledge, Polity, New York. Web.

CEBR 2013, The impact of the European Union on the UK labour market. Web.

Centre for Economics and Business Research 2013, Impact of EU labour on the UK. Web.

Centre for European Reform 2014, The economic consequences of leaving the EU: The final report of the CER commission on the UK and the EU single market. Web.

Chan, S 2016, Brexit: what if the UK left the EU and could be more like Norway. Web.

Charter, D 2012, Au Revoir, Europe: What if Britain left the EU, Biteback Publishing, London. Web.

Copeland, D 1996, ‘Economic Interdependence and War: A Theory of Trade Expectations’, International Security, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 5–41. Web.

Desch, M 2015, ‘Technique Trumps Relevance: The Professionalization of Political Science and the Marginalization of Security Studies’, Perspectives on Politics, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 377–393. Web.

Eldring, L 2008, Mobility of Labour from New EU States to the Nordic Region: Development Trends and Consequences, Nordic Council of Ministers, London. Web.

Forde, S 1995, ‘International Realism and the Science of Politics: Thucydides, Machiavelli and Neorealism,’ International Studies Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 141–160. Web.

Gregory, I 2003, Ethics in Research, A&C Black, New York. Web.

Hesse-Biber, S 2010, Mixed Methods Research: Merging Theory with Practice, Guilford Press, New York. Web.

Hothi, N 2005, Globalisation & Manufacturing Decline: Aspects of British Industry, Arena books, London. Web.

House of Lords – Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2008, The Economic Impact of Immigration: 1st Report of Session 2007-08, The Stationery Office, London. Web.

Isaac, J 2015, ‘For a More Public Political Science’, Perspectives on Politics, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 269–283. Web.

Keohane, R 2009, ‘The old IPE and the new’, Review of International Political Economy, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 34–46. Web.

MacShane, D 2015, Brexit: How Britain Will Leave Europe, I.B.Tauris, London. Web.

Mantzavinos, C 2009, Philosophy of the Social Sciences: Philosophical Theory and Scientific Practice, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Web.

Mearsheimer, J 2001, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, Norton & Company, New York. Web.

Mearsheimer, J, & Walt, S 2013, ‘Leaving theory behind: Why simplistic hypothesis testing is bad for International Relations’, European Journal of International Relations, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 427–457. Web.

Miller, V 2016, EU Referendum: Impact Of An EU Exit In Key UK Policy Areas. Web.

Minford, P, Gupta, S, Phuong, V, Mahambare, V, & Xu, Y 2015, Should Britain Leave the EU?: An Economic Analysis of a Troubled Relationship, Edward Elgar Publishing, London. Web.

Rubin, A, & Babbie, E 2009, Essential Research Methods for Social Work, Cengage Learning, London. Web.

Sarantakos, S 2012, Social Research, Palgrave Macmillan, New York. Web.

Seale, C 2004, Social Research Methods: A Reader, Psychology Press, New York. Web.

Sjoberg, L 2013, ‘Towards Trans-gendering International Relations’, International Political Sociology, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 337–354. Web.

Sloane, P, Latreille, P, & O’Leary, N 2013, Modern Labour Economics, Routledge, London. Web.

Tournier-Sol, K, & Gifford, C 2015, The UK Challenge to Europeanization: The Persistence of British Euroscepticism, Springer, London. Web.

Weber, C 2014, ‘Queer International Relations: From Queer to Queer IR’, International Studies Review, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 596–622. Web.