Introduction

The epoch of British colonialism in India was characterized by considerable changes that influenced Indian life and still echo nowadays. Today’s Indian economy is the result of a complicated period, where traditional order mixed with the British one and dissolved in it forever. The problem of the impact of British colonialism on the Indian economy inspired this research paper. The paper is based upon results of research in this question, statistic data, and economic indices analysis that help to understand the problem profoundly.

The British conquest policy dictated its rules in the Indian economic sphere. The traditional Indian economy could not but adapt to British rule. Its modification was long-term and painful for the country’s population. It is impossible to reveal the colonial impact on the Indian economy without an overview of the industrial revolution that changed the world’s way of life. Of course, the British Empire’s colonial policy had its advantages and disadvantages for India. Hence, the research paper intends to reveal the problem of British colonialism in the Indian economy from different points of view.

There has been much research on the issue of British impact on the Indian economy, and it offers a valuable contribution to the economic history of India, and peculiarities of Indian economic life in the XIX-XX centuries. The period of British raj was a challenge for the traditional Indian economy, based on hand-loomed weaving, jari, brassware, and other industries. New economic policy relied on basic Indian industries: cotton textile industry and the agricultural sector. They became the main source of the British Empire’s enrichment. Indian textile and agricultural products were intended to be exported, mainly. Raw cotton, rice, tea, jute, etc. were cultivated in India. Indian cloth was an essential element of the Indian market. The products of textile and agricultural industries brought large profit for the British Empire; it made the most exploited Indian population poor and famished debtors.

Therefore, there is much material on which the present research paper will rely in making observations and inferences about the true impact of British colonialism on the Indian economy on the whole, and on particular fields of industry such as the cotton textile industry and the agricultural area of work.

There is much research in the field of the colonial period of the Indian existence, implying the agile interest to the exploration of Indian-British relations, especially in the period of the British reign in India. For example, Jayapalan (2008) dedicated his book to Indian economic history and outlined its peculiarities throughout the centuries. Tomlinson (1996) investigated the Indian economy in general within the limit of the period, when India was one of the British colonies. Roy (1999) was interested to examine the traces of Indian traditional industry in its economy of the colonial period. Watterson (1985) proved the success of British international policy and showed its essence for the developing countries. Thus, the present topic is quite relevant for studies in the history of world economies, and the works of these authors, alongside a much wider body of literature, will give a deeper insight into the present research field.

Background and Purpose

The background of the problem is connected with the researched fields of the study and the nature of the problem itself. The problem of British colonial policy in the Indian economy has been in the scope of scientific interest for a long time. The intervention of the British Empire cannot be imagined without the implementation of a new policy in the colonized country. For this reason, the Indian economy faced changes that influenced the country’s life till nowadays.

The researchers investigated this question profoundly. Roy (2006) described the Indian economy during 1857-1947. In the book, he divided the country’s economy into two periods: before and after 1857 that was the starting point for the modern Indian economy. Rothermund (1993) examined Indian economic life starting from the pre-colonial period till the end of the XX century and proved the essence of traditional Indian industries for its future development. Kohli (2001) was interested in the connection between the Indian past and its modern democratic success and founded that the period of British raj was one of the notable periods for the Indian economy. It is a widely-known fact that the historical context of a country predetermines its future condition. The Indian way to independence was long and challenging.

Since India became one of the British colonies, its way to economic progress has been complicated. The cruel policy of the colonizing country led to the population’s disappointment and revolts. It means the high level of resistance of the old way of life toward another one. Under the British Crown, India experienced positive and negative aspects of a new way of life, where the traditions played an essential role. As Roy noted Indian pre-colonial economy had an agricultural character; also, Indian society cultivated certain traditional crafts that enriched the local economy. Consequently, the adaptation to the British economy presupposed the mixture of traditions and innovations. Some researchers believed that the advantages of the global industrial revolution proved the British successful impact on the Indian economy.

India was attractive to the British crown by its spices and handicrafts, the authentic industries that historically developed on its territory. The colonizer-countries always took advantage of the labor and skills of the population, and the country’s natural resources for enrichment. The colonial policy of the British crown turned India into the raw-material appendage of the metropolis, and the market for its industrial products. It was evident that the British increased their capital; nevertheless, the unfair policy toward the exploited local population exhausted their patience. For this reason, the waves of the national liberation movement were a natural reaction of the pinched Indian nation.

However, it is impossible to let aside the progress and advancement of the Indian economy that the British rule brought about to the country. Although the predatory policy of the colonizer-country was obvious, the colonial period gave a powerful impulse to the Indian economy and speeded up its development. Besides, one can agree that the exploitation of the Indian colony was one of the main sources of the industrial revolution in England.

The present research paper possesses a certain scientific value; the collected statistical data and some figures show the territory of India under British rule, and Indian products and industries. Hence, it will allow revealing the key to British economic success that was achieved with Indian hard labor. Since the purpose of this paper is to take a deeper insight into a certain period of the Indian economic development, namely the times of the British rule, the research findings are intended to serve as a sufficient basis for understanding all economy-related, industry-specific implications of the British intrusion in the Indian economic development.

Problem Statement

It is impossible to say for sure, whether British rule led to positive or negative consequences for India. The economic life of feudal India was characterized by the development of its agriculture and traditional handicrafts. Exactly the farming industry was the country’s economic base. When the British came, India proved its incapability to resist colonization. The new policy influenced all spheres of Indian life, especially the economy. Thus, one may believe that British colonialism affected the Indian economy negatively.

In the past, India attracted European colonizers, who extensively exploited its hard labor, natural resources, and traditional industries for capital formation. India took an essential part in the trade companies of some countries that were ready to struggle for it. Its trade roots were known to the entire world. Naturally, British colonial policy led to the inevitable changes in the Indian economy, which were not always bad, but very often progressive and positive. Therefore, it seems vital to explore a wide range of implications of the British rule in India and its impact on the development of colonial India, the Indian economy on the whole, and some dominant industries (such as cotton textile and agriculture) in particular to be able to produce a set of relevant conclusions on the true contribution of Imperial Britain on the Indian economic development.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The problem statement needs the corresponding research questions and hypotheses. The purpose of the paper can be realized if some questions will be answered and some developed hypothesis will be verified. This research paper is focused on the following research questions and null and alternative research hypotheses:

- RQ 1: What industries were affected the most by British-led economic reforms?

- RQ 2: What changes were visible in the field of cotton textile?

- RQ 3: What reforms could be observed in the area of agriculture?

Importance of the Study

The study is important because the topic of this research paper is of broad scientific interest. It contains not only the general information about the Indian traditional economy and the colonial policy of the British crown in the country but the information about its influence on the Indian economy as well. As the research paper raises many additional problems (national liberation movement of the Indian population, cultural elements that could not be destroyed by the British raj’s policy, etc.), this study may open the directions for further, more comprehensive, wider, and more profound research in the field. The results of the paper may serve for the overall scientific benefit. Also, it may serve as the basis for the elaboration of possible economic strategies intended to overcome the current weak aspect of the Indian economy, conditioned by the historical past of the country.

Limitations

The present research paper contains a set of limitations that may hinder the generalizability of its findings and results. Primarily, it is necessary to remember that the research paper examines the period of British colonization in India. Some researchers agreed that the period from 1857 till 1947 may show the limits of British raj in Indian colonies (Roy, 2006).

More than that, the presented statistical information is based on the collected data for a certain period. This research paper contains veracious information about the assortment of Indian-produced goods and industries that enriched the global market (especially, the British one) during the period of 1857-1947. Thus, the presented economic indices can be considered adequate if the problem is examined within this limited period.

Scope of the Study

As the paper on economic history requires data collection concerning the problem under research, the economic data for 1857-1947 are presented here. To achieve the purpose of the paper and prove its hypotheses, the concept of British colonial policy is explored. The period of the British rule in India is the focus of the research, grasping the significant economic and industrial changes in India from 1857 to 1947.

Literature Review

It seems to be necessary to examine some key points in Indian history and economy to achieve the purpose of the research paper. The researchers’ results about the traditional economy of India, British raj, and its economic policy in India will be discussed. It will allow using this base for further analysis of the problem.

Traditional Economy of India

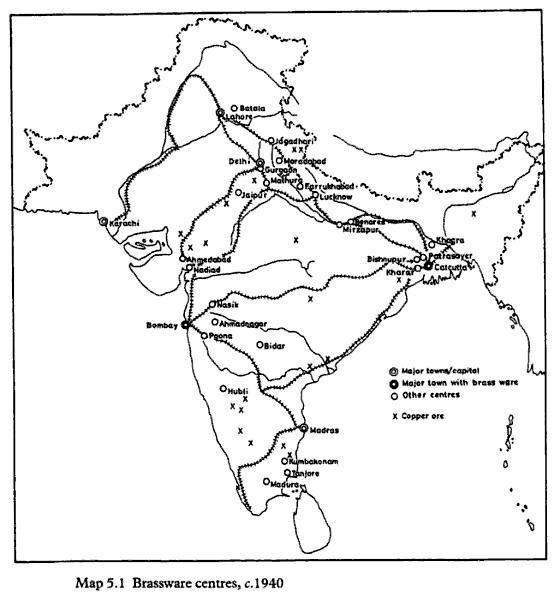

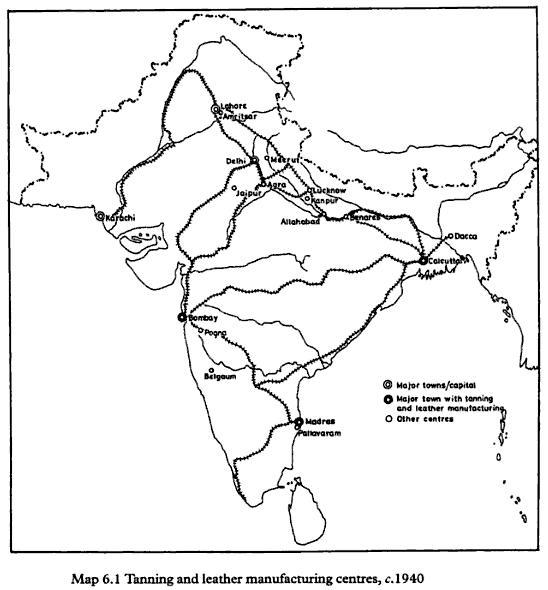

Before the research paper proceeds to the period of British rule (1857-947), it is essential to deepen into the background that will allow understanding of the Indian traditional economy. For centuries, India has followed its traditions in the economy. The traditional economy comprises the following elements: traditional industries agriculture and cattle breeding. Roy (1999) believes that in its economy, India is based on handloom weaving, brassware (see Appendices, fig. 1), jari (gold thread weaving), carpets, and leather (see Appendices, fig. 2). The author thinks that traditional industries of India combine three main features: “tool-based technology, non-corporate organization, and pre-colonial origin”. Proceeding from the book, one may see that the main Indian industries were the result of a skillful and crafty population. When the British Empire turned the country into its colony, these local industries played an essential role in the economic history of South Asia. Artisanal textiles were extremely significant for the Indian economy. The cotton textile was the most spread industry in the country. The researcher notes that experienced tool-based technology allowed India to develop the economy with the help of a hand-woven cloth. Thus, the creativity of the population led to products of high quality that were appreciated all over the world.

Also, India could offer its agricultural goods to the world. The country’s economy was rooted in local agriculture: the hard labor of the Indian population greatly contributed to the overall development of the economy. According to some researchers, rice, wheat, barley, bajra, maize, jowar, sugar cane, and cotton were key elements of Indian agriculture. Hence, such products provided the country’s economy with vital power. Agricultural prosperity speeded up the developmental process. Cattle breeding provided the country with meat, milk, and other products. Punjab was the primary center for Indian cattle-breeding. Later, a large number of cattle (especially, bovine cattle) was exported to other countries of the world.

Some researchers dedicated their books to the Indian economy, where the East-India Company and Mughal Empire played a key role. According to the authors, the Mughal Empire positively influence the state economy. One of the main features of this period (mid. XVII c.) was a uniform revenue policy, centralized administration, and a network of inland trade that expands overseas commerce that gave powerful stimuli to the Indian economy. However, the maritime power of European countries led to the declining Mughal Empire. The struggle for supremacy ended with the British victory that resulted in the colonial economic policy of the British Empire.

Besides, the context of the East-India Company contributed to economic status and development. Proceeding from the book, one sees that East-India Company included several trade communities in some European countries. In each of these countries, there were established companies that had a monopoly right to trade with East India. However, the struggle between French, Holland, and British East-India Companies influenced the future of the country. However, time passed and the economy faced challenges that were too difficult to be overcome.

Jayapan (2008) considers India to be a “workshop of the world” in the XVIII century, because this country supplied the entire world with everything necessary: food, cloth, etc. Owing to the developed shipping network, it was possible to deliver any article to any country in the world. Nevertheless, despite the fertile lands, the country had low-scale farming. The decreased level of local agriculture could not provide India with economic wealth: most of the population constituted poor people or peasants. The devastation of the country continued, and India found itself on the way to economic decadence. Unprofitable sectors, such as handicraft and agriculture could no longer enrich the local economy.

Taking into consideration everything mentioned, one can note that traditional industries, agriculture, and cattle breeding built the base for the traditional Indian economy that proved its high potential. The Mughal Empire and East-India Company positively influenced the economy and gave a stimulus for further development. However, the cruel struggle of European countries for India posed a threat to the country’s economy that needed modification and renovation in the context of the developed British economy. The colonial status of India had both advantages and disadvantages for the country’s development and population’s life.

India as a British colony: British Raj

As it was mentioned, the glorious Mughal Empire was declined by British power. In 1856, the larger part of India was under the British East-Indian Company. At the same time, the economic situation of the country provoked unrest in people’s masses. Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 was inevitable: Indian troops that served for the British East Indian Company raised the national spirit of India that strived for independence. Although the rebellion was repressed, it cast challenges for British control. As result, the East-India Company was liquidated; all the country passed into the British Crown. The era of British raj started in 1857 when India became a British South Asian colony.

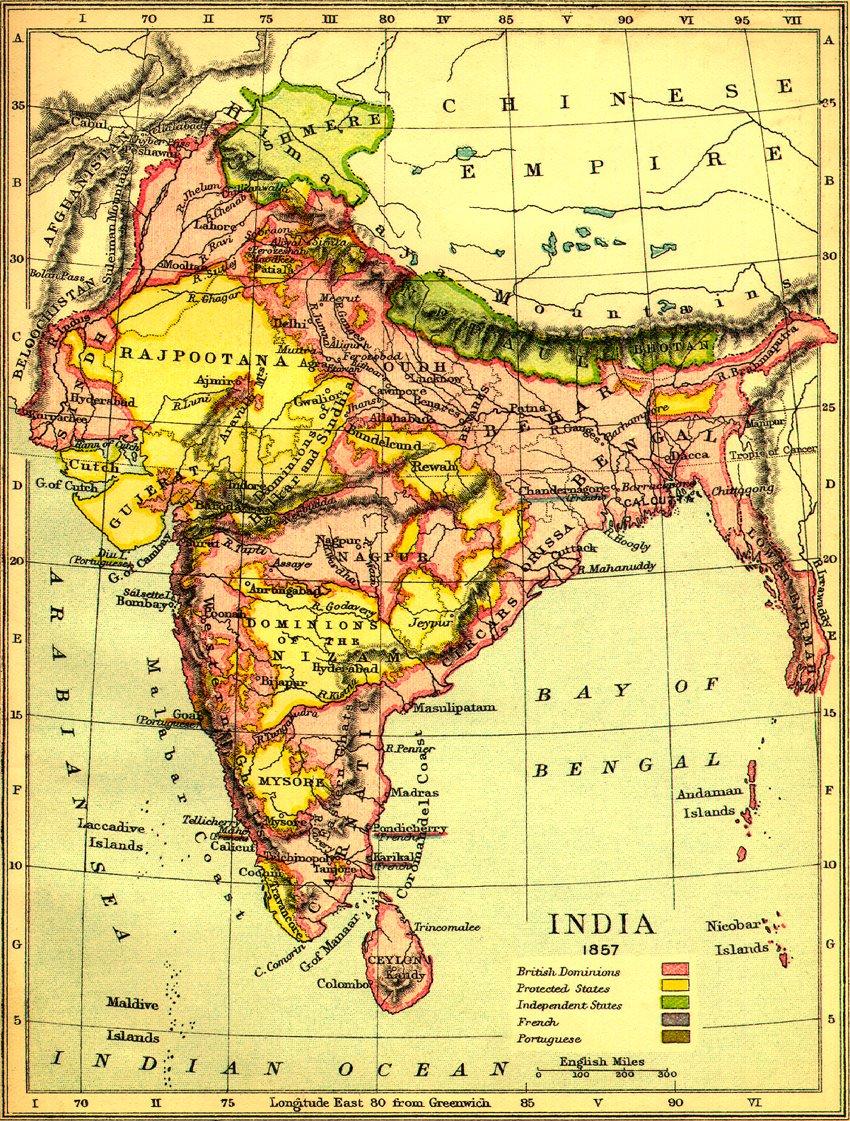

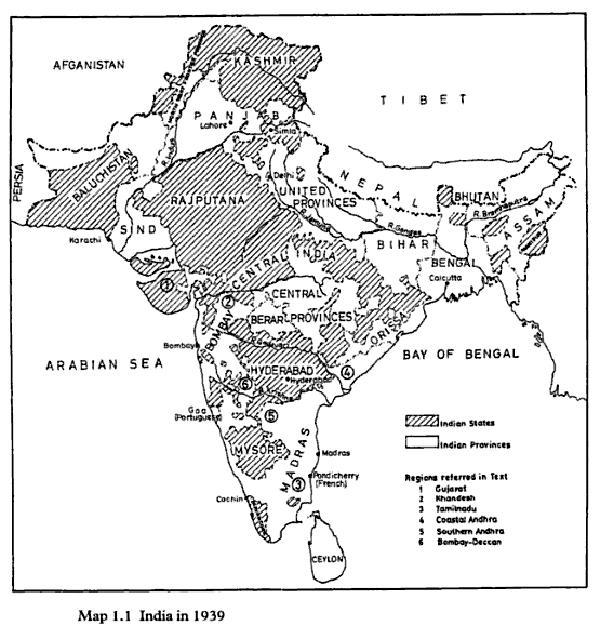

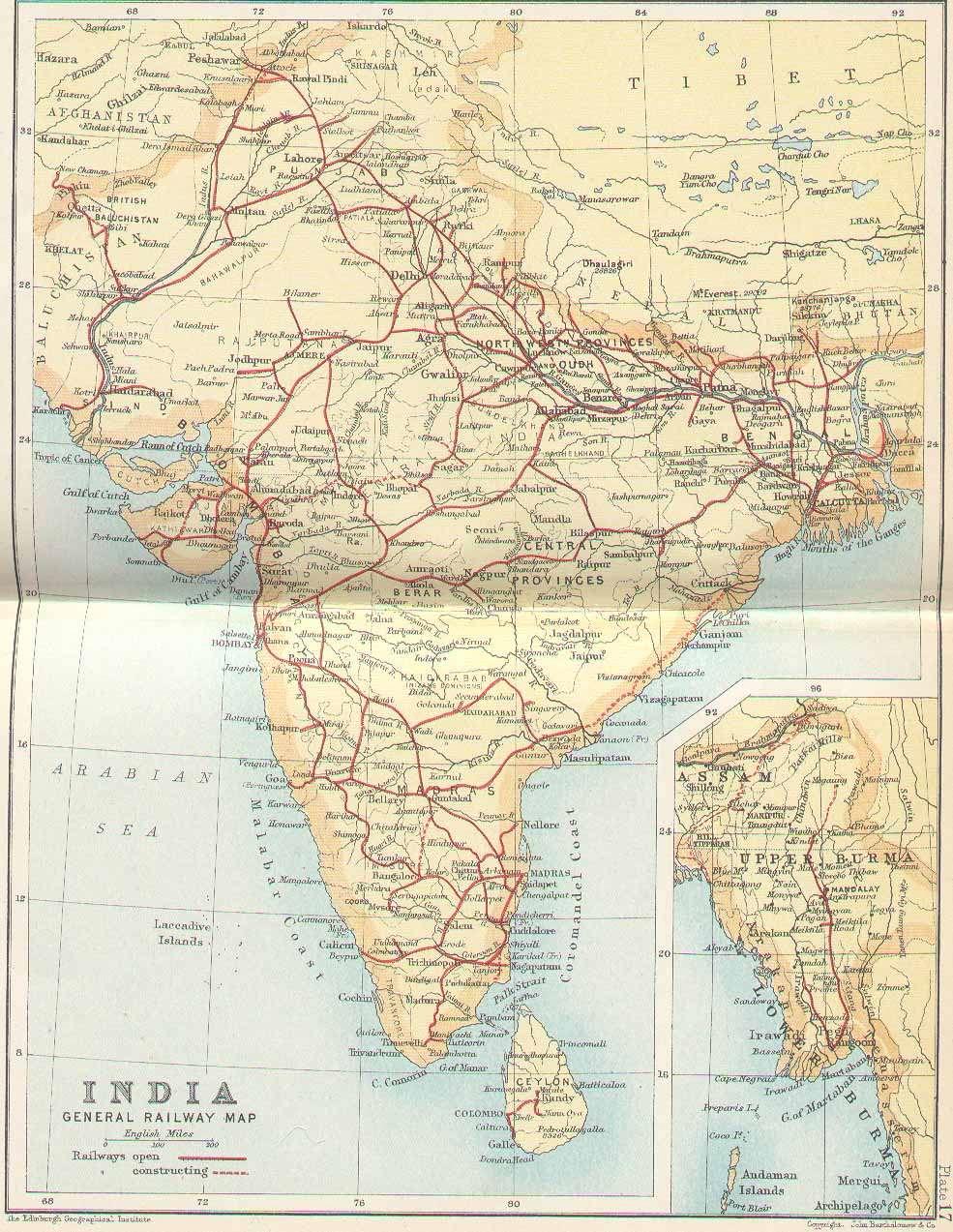

In 1857, British queen Victoria became the empress of India. The powerful British Empire finally gained control over India and started to implement its colonial policy, peculiar to British Imperialism. Figure 3 (see Appendices, fig. 3) shows the territory of India at the beginning of the British raj. One may see that the British Crown dominated not over the whole country: some independent states formally depended on the Crown. Figure 4 (see Appendices, fig. 4) shows Indian states and provinces at the end of the British raj period.

It is necessary to outline the characteristic features of British colonial policy in India. Hobson (2005) gave his definition to the phenomenon of colonialism; its features can be noted in British imperial policy in India. According to the author,

“Colonialism, where it consists in the migration of a part of a nation to vacant or sparsely peopled foreign lands, the emigrants carrying with them full rights of citizenship in the mother country, or else establishing local self-government in close conformity with her institutions and under her final control, may be considered as a genuine expansion of nationality, a territorial enlargement of the stock, language, and institutions of the nation”.

However, the distance between the British island and its Indian colony specified the monopoly’s policy. The period of British raj may be considered as a bright example of capitalistic penetration of the monopoly country into the life of the colony. British colonial policy was based on exploitation through political and economic means. Indian population experienced hard times under the British Crown: “white man’s burden”.

Cain and Hopkins’ (2002) book may reveal the nature of British colonial policy. According to the researchers, the British exploited natural and people resources, and tended to monopolization world trade. They liquidated intermediary countries, optimized the trade roots and Indian sale market. As India was a distant colony, the British had to provide the Indian market with security. The interior policy was cruel. The predatory British policy expressed in military-confiscation methods, killing of the native population, violence, etc.

Explaining the meaning of imperialism, Cain and Hopkins (2002) underline that imperialism was the highest stage of capitalism in a global context (“absorbed by the elites”). Imperialism may be understood as “one of the methods by which that elite can prosper and continually renew itself. The period of British raj proves this theory.

The colonial policy of the British Crown became a hardship for millions of Indians. As India was a feudal country, the government introduced the zamindar system to facilitate the process of agricultural tax collection. This way, in the provinces of British India, there appeared the groups of zamindars – feudal inherited landowners, who had the right to collect heavy taxes from their peasants. This policy helped to extract the maximum income from the Indian population.

The transition from manufacture to factory industry dictated new rules in the colonial policy. India became an agrarian and raw-material-producing appendage: agricultural development and market outlets of Indian industrial products were sources of the increasing capitalistic industry of the metropolis. The British government in India increased the amount of export from India (cotton cloth) that resulted in British enrichment.

The Indian colony, for the British Crown, was a vital source of finance accumulation, and the tool to speed up the process of British economic development. In the colonial trade, export prevailed over import. For this, the British governance limited and, sometimes prohibited import from other countries. Gradually, India was turned into the market outlets of English goods. It led to the cut off of export of goods of Indian production. In its turn, it resulted in the mass destruction of Indian craftsmen. The development of national industry was artificially retarded. One of the purposes of British colonial policy was to enforce the Indian population to buy English goods. Nevertheless, there was a necessity to facilitate colonial policy in world trade using free trade. For this reason, principles of free trading were applied in the sphere of the British-Indian trade market. It pushed off the excessive English import, and avoided inflation; also, it allowed exporting the produced Indian goods. Hopkins and Cain explain that the free market was an opened door that could be used by foreign rivals.

As British raj is characterized by advantages and disadvantages for Indian life, his period may be considered ambiguous. On the one hand, it had negative effects. All the goods, imported from India to the British Crown, were acquired using exploitation of the population. India was flooded with the goods of English production. There was a certain decline in the local industries (for example, the cotton industry). The financial condition of India was horrible. However, there was a positive influence of the British rule in India, as well.

Expansion of the British crown was realized not only in the political and economic spheres of Indian life but in culture, as well. For example, the practice of Sati was considered an inhuman cultural expression; for this reason, it was outlawed: since that time, Indian widows could remarry. Moreover, the British government in India decreased the criminal rate: for a long time, numerous travelers had been killed by local thugs. Also, the situation with health care and sanitation was improved in the country. The technical progress led to the appearance of the telegraph, postal service, and railroads. In the period of the British raj, India became the country with a successfully-developed railroad network. Figure 5 shows numerous railways all over India in 1893 (see Appendices, fig. 5). This way, the British turned the imperial civilized standards into global ones. The industrial revolution in England resulted in certain technological development in India. However, in the book, Hobson shows two aspects of the industrial revolution. According to the author, it

“is one thing when it is the natural movement of internal forces, making along the lines of the self-interests of a nation … with advancing popular self-government; another thing when it is imposed by foreign conquerors looking primarily to present gains for themselves, and neglectful of the deeper interests of the people of the country”.

It is evident that when the British provided India with the achievements of the industrial revolution they pursued their financial benefits: the more technological progress in the country was introduced the more profit it could bring. Nevertheless, in general, British control operated to the benefit of an average Indian citizen.

The British paid much attention to the education of the population. Thomas Babington Macaulay introduced a new system of school education in India. There were established special educatory centers for training and examination of Indian elite (disciplines on civil service, instruction of young girls as future wives. Moreover, there was created an Indian medical service. Primarily, Indian and English armies took advantage of it; however, in peaceful times, Indian doctors provided the local population with their services. Also, the period of British raj gave India new roads, bridges, barrages.

Despite the fact, that price of British colonialism was high for India, the period of British raj was full of colonial reforms that influenced the country’s life forever. British governance brought relative stability and order into Indian society. The effects of British raj were ambiguous, as there was an improvement of some spheres of Indian life in the prejudice of others.

British Raj’s Economic Policy

When most of the Indian territory was under British rule, it was evident that the colonial economic policy of British raj would be aimed at the enrichment of the British Crown. Although slavery was abolished by the British, the colonial rulers implemented the strategy of excessive taxation that helped to extract the country’s resources to the benefit of the British Empire. As some researchers note, the amount of “economic drain” was equal to 0.04-0.07% of Indian national income.

In the article, Maddison (1971) outlined the key elements of British colonial policy. According to the author, British imperialism pursued economic aims, not evangelical. It was not blinded by Christian fanaticism and westernized India in its way. When the British chose their policy in India, they had several kinds of interests.

First of all, the primary aim was to come into a monopolistic trading status. The British capitalists invested in banking and shipping services that favored free trade. One of the monopolistic privileges for British capitalists was to enjoy the policy of free trading: India turned into a large market for British products and a source of raw materials. Second, India provided the British middle-class portion of the population with employment; in its turn, their remittances contributed to the British budget. Third, the control over India could give the British Crown prevailing positions in the world: it strengthened its power (especially, military power), and allowed controlling the territory of South Asia.

Maddison (1971) believes that the economic policy of British raj did not tend to develop the Indian economy. They did not protect the Indian textile industry. The Indian population was poorly technically educated. Of course, India borrowed some British concepts of property, but it was not convincing too for improvement of the local economy. Most of all, British raj’s economic policy was more beneficial for the upper class of population: British aristocracy, a bureaucratic-military portion of the British population, capitalists, landlords, and professional classes. In contrast to the Moghul Empire, British administrators did not carry out efficient investments in the agricultural and industrial sectors of the Indian economy.

Gradually, India transformed into the home for the British elite spent their Western lifestyle on Indian ground. There appeared new towns, where urban life boiled with the energy of the British. In this world, the Indian population was the least essential people. Although the Indian population increased, there was extremely small income and output per capita. According to Maddison (1971), the economic and social impact on Indian development was relatively limited. This way, the period of British raj can be considered as a bright example of the typical British colonial policy that retarded the economic potential of India.

However, during the British raj, there was a certain reformation of agriculture. The British administrators transformed the traditional property rights of India into private property by the Western model. The British rulers reinforced the system of land tax collection through zamindar authorities. Their hereditary status excluded administrative functions; they paid low rental payments, and could not be evicted. Their rights were abolished only in 1952. The British established a profitable and effective peasant tenure system that enriched the overall Indian income to the British Crown. Moreover, as titles appeared, it was possible to mortgage land that improved the status of moneylenders who rooted out inefficient landowners.

The income of landowners rose for the reason of certain factors: heavy land taxes and rental payment. Under British raj, land scarcity led to the wide-spread phenomenon: the class of landless agricultural laborers. At the same time, rural capitalists had the rights to sell and buy land freely, and increase the number of products in such away. The British rulers faced a certain challenge in Indian villages: most of the population was illiterate, and had problems with a technique that helped to achieve high product performance. As agriculture grew, the Indian population increased. According to Maddison (1971), it “grew from 165 million in 1757 to 420 million in 1947”.

Also, almost half of British Indian territory was successfully irrigated (primarily, Panjab and Sind). For example, the territory near Afghanistan turned from the lifeless desert to a highly-populated area with high productivity: wheat and cotton were exported to other countries and sold on the territory of India. At the end of the British raj, “irrigation investment covered nearly 25 million acres of British Indi”. Nevertheless, the development of cash crop trade would not be possible without investment in the transport system (railways, steamships, the Suez Canal).

Farming based on plantations, as well. Indian hard labor on plantations is famous all around the world. On plantations, tea, jute, sugar, indigo were cultivated. Maddison (1971) underlines: ‘in 1946, the two primary staples, tea, and jute, were less than 3.5 percent of the gross value of crop output”. Probably, the British tea tradition rooted in the successful British East-India Company and increased tea exports from India to the British island. Thus, Indian tea became a part of the English tea tradition.

Unfortunately, agricultural technology experienced decadence under the British raj. The agricultural output was extremely small. The statistics show that “only a 3 percent increase in crop output in British India from 1893 to 1946, i.e. a period in which population increased 46 percent”. At the same time, Indian home spinning (a traditional activity of Indian rural women) was reduced. However, in contrast to hand-loom products, textile consumption was high.

In Page and Sonnenburg’s (2003) book, one may find information about successful railway network building. In the 1860s, there were constructed first railway lines. The Suez Canal allowed Bombay to be the first Asian city in commerce: it was called the “Gateway of India” (in 1853, from this city, there was built the first railway line). It turned the city into the highly industrialized cities of India.

In the context of a developed railway network, the coal mining industry achieved significant results. The output of this industry reached about 16 million tons. Also, exports of raw materials were popular. Maddison provides the corresponding data. Among Asian countries (such as China, Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Thailand, etc.), India was the most successful one in exports. From 1913 till 1950, the export increased from 786 million dollars to 1,178 million dollars. Thus, British raj’s economic policy had its own positive and negative effects.

In general, the researchers’ views can be referred to two main streams: those, who considers India to be a potential but weak country against the British Crown’s background (nationalist views), and those who sees benefits and costs of the British raj for Indian economy (newer views). Roy, Jayapalan, Iyer, Kumar, Rauchaudhuri, and Desai supported nationalist views. According to them, India had a potential economic base for further development: Indian traditional industries and its economic status in the period of the Mughal Empire predetermined slow but certain progress. However, the period of British raj affected negatively the Indian economy, as the exploitation of natural and human resources and decline in traditional economy flourished. Hobson, Cain and Hopkin, Maddison, Duiker and Spielvogel, Page and Sonnenburg are the representatives of newer views. They consider the British raj as a period full of both negative and positive effects on the Indian economy. Although the Indian traditional economy was retarded, certain reformations in agriculture and industrial spheres had a positive influence on the country. Besides, using the British Empire, the Indian economy experienced the period of the industrial revolution.

Analysis of Research Findings

All the data and researchers’ results allow making the following analysis inferences. Taking into consideration a wide range of economic implications of the British raj’s period, one may present the corresponding research findings. Here, the problematic aspects of the research questions will be discussed and revealed, including the overall impact on the economy, and the detailed discussion of some separate economic fields; besides, the objective of the research paper will be achieved.

The “stationary bandit’s” policy: positive and negative aspects of the British raj for the Indian economy

Colonial India faces numerous challenges in the period of the British raj. Proceeding from the literature review, one can see that effect of British colonial policy affected India ambiguously. Thus, discussion and analysis of the data of the period (1857-1947) and events that happened in India under the British Crown seem to be necessary for realizing the dual nature of British colonial policy in the Indian economy. As it was mentioned, India became a British colony in 1857. Since that time, India has passed a long and difficult way to freedom.

According to Mancur Olson (2000), a type of government presupposes certain economic effects. One of his significant works reveals the idea of the state as “a stationary bandit”. In the context of the British-Indian relationship, it is possible to note that colonial power has an incentive to invest in the development of a colony so that more taxes can be collected. However, it is necessary to deepen the idea of a stationary bandit to understand the phenomenon more profoundly.

Olson analyses the policy of the government implied on another territory. A “roving bandit” may settle down and become a ruler of a captured territory. Thus, a roving bandit turns to a stationary bandit (a positive civilized process) who wants to have a long relationship that would bring him maximum benefit through minimal economic encouragement. When the British colonized the country’s territory, India became a victim of a stationary bandit. Being a tyrant on Indian land, the British Crown seems to be a stationary bandit that monopolizes the Indian economy to take advantage of it. At the same time, the British Empire is concerned with certain economic development that would increase the income.

The policy had a dual nature. As the stationary bandit, the British government “with continuing control of an area wants to make sure that the victims have a motive to produce and to engage in mutually advantageous trade”. Thus, the severe tax policy in India was evident, as it produces high income for the British Crown. Moreover, a stationary bandit gives “an incentive to provide public goods that benefit his domain and those from whom his tax theft is taken”. The British social policy in India deterred the possible crimes; moreover, during the period of the British raj, the Indian population became more productive.

The tyrant (the British Crown) has an incentive to encourage the economy of the captured land to a certain extent. At the same time, it protects the territory (citizens and property) from roving bandits. However, the negative effects are notable. Consequently, it is essential to analyze the negative and positive aspects of the British raj for the Indian economy to trace the effects of stationary bandit’s policy.

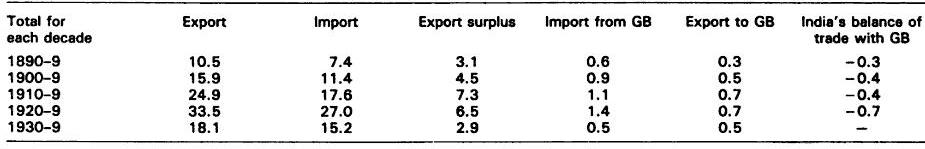

Proceeding from Rothermund’s data, illustrated in figure 6 (see Appendicitis, fig. 6), one may note the constant negative tendency in the Indian economy. From 1890 till 1930, British export prevails over Indian imports. As one can see, in 1890, export was equal to 10,5 %; import – 7,4 %. Even in the period of British economic depression, there is the same tendency; in 1930, export equals to 18,1 %; import – 15,25.

The period of British raj was full of exploitation; the Indian population overcame famine and poverty. As the national self-consciousness strengthened since the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857, the Indians saw more and more obstacles on their way to freedom. The presence of British immigrants in India was only part of general colonial policy. The phenomenon of multiracial coexistence provoked racism, sometimes. Practically all the population served for the benefit of the upper class and the British Crown. The local population felt the oppression in the economy, most of all.

The Indian economy was exhausted and weak. All the improvements were aimed to gain profit for the British Empire, not for the Indian population. The British raj expanded the railroad system to sell English goods all over India. It led to tragic consequences for the Indian economy – the government limited or excluded the opportunity to export Indian products. All the country was enforced to buy only English goods; it extremely weakened the economy.

The established revenue system made peasants poor people. “Land tenure system” allowed the British government to collect heavy land taxes. Indian land inequality is rooted in the presence of big landlords. At the same time, there was a deficit in the investment of Indian economic sectors. Thus, despite the presence of fertile lands, the Indian rural population showed low productivity. British treasured India for its potential, not actual profit.

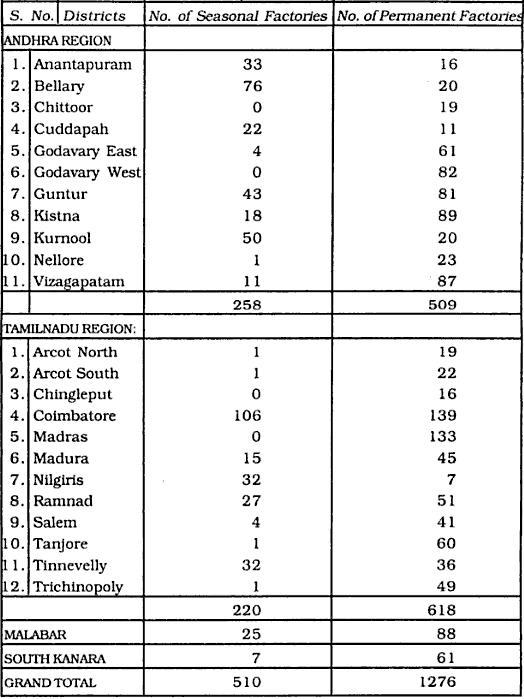

Thus, for the period of the British raj, the British rulers extracted as many benefits as they could from India. The population of India was enforced to produce raw materials for the British Empire’s manufacturing. Through the large market, it was possible to sell British goods in the prejudice of the Indian ones, because the trade competition was prohibited for India. Imported British textiles pushed off the Indian handloom textile industry. India paid too high a price for being a “jewel in the crown”. This way, India became the most valuable colony for the British Empire, as it brought profits that enriched it. By 1939, there were numerously seasonable (510) and permanent (1276) profitable factories that brought large income to the British crown (see Appendicitis, fig. 7).

Besides, such agricultural products as jute (a fiber, used for cords, sacks), tea, coffee, opium, etc. were in the highest demand. As India was a British colony, Britain was the powerful trade rival that tried to displace other countries, like the USA, Russia, and others. At the same time, the British restricted Indian traditional production. The predatory policy led to famine in Indian villages: the demand for cash crops resulted in the absence of vital food for the population. However, there were some positive features during the British raj.

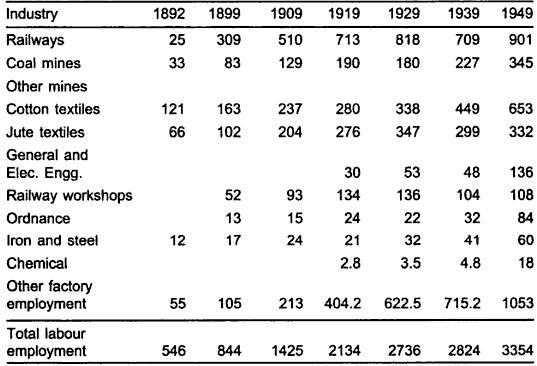

By the British rule, India faced numerous positive moments that influenced the country’s economy. Through the international trade and free-trade policy, India was opened to the world that could use and benefit from Indian products. Other countries (primarily, the British Empire) had an opportunity to buy Indian products. Moreover, during the British raj, many Indians were employed. Figure 8 (see Appendicitis, fig. 8) illustrates the industries that provided the Indian population with employment. Proceeding from the table, one can see that railway (818 thousand in 1929) and cotton textile (449 thousand in 1939) industries have high indices of employment.

The industrial revolution can be considered a valuable contribution of the British to India. Many technological devices appeared in India that facilitated to transmit the information (via telegraph and telephone lines), or transport goods by railway roads. Indian railroad network was the third-largest railroad in the entire world. The railroad brought unity among the Indian population of numerous regions. The modernization of the country was expressed in the building of bridges, dams, and roads, as well. Healthcare and educational systems were improved; literacy among the Indians increased.

According to Williamson (2008), the period of British raj reduced India’s world output to a minimum. The manufacturing output of India in the period of 1750-1939 shows the denaturalization, resulted by the British raj (see Appendicitis, fig. 9). The percentage indices show that in the pre-British Raj period (1830), the output was equal to 17,6%, while during the British raj (1880) it was 2,8%. At the same time, China has a more leading position (in 1830: 29,8%; in 1880: 12,5%). As one can see, there was a negative tendency for the Indian economy. The main reason for this phenomenon lies in the fact that British trade domination did not give any opportunity for the Indians to develop their industries for the benefit of the Indian economy.

As the condition of the Indian economy was horrible, it caused national unrest, animosity, disaffection, and distrust of the British that were Western aliens on Indian ground, who treated India as their purse. The seed of national evolution, sown by the Sepoy, grew in the Indian population that sounded the death knell for the British raj. The effects of the British raj were ambiguous for the Indians. On one hand, the stationary bandit gave lots of opportunities to the Indian population for possible economic development (free trade, the industrial revolution, etc); on the other hand, the economic potential was artificially suspended, because the British Empire’s domination oppressed the Indian population and its traditional economy.

Changes in Cotton Textile

As cotton textile was one of the basic industries of the Indian economy, it could not but experienced the period of the British raj in its way. Following one of the research questions, one can reveal some visible changes that appeared in the field of cotton textile. It is possible to mention basic negative and positive effects in the Indian textile industry.

The cotton textile industry faced negative consequences of the British raj. Before 1857, India exported cotton fabric all over the world. However, the British changed the situation: the reversed position of the Indian cotton textile industry reflected Britain’s economic demand. India turned into the main supplier for British manufacture (it exported raw cotton), and importer of British cotton textiles.

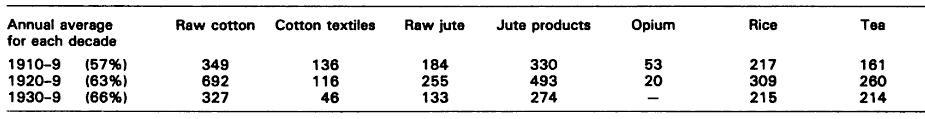

Moreover, figure 12 (see Appendices, fig. 12) illustrates that the export of raw cotton and cotton textiles reduced. In 1920, the export of raw cotton was equal to 692 million rupees, while that of cotton textiles – 116 million rupees. For the reason of the economic devolution of the 1930s, India shows poor indices: raw cotton: 327; cotton textiles: 46.

It is possible to outline the main characteristic features of Indian cotton textile under the British raj. Even in pre-colonial times, India demonstrated high potential in textile production. It is necessary to underline that Indian spinning skill was notable. For example, in contrast to European spinners, Indian ones could produce pure cotton cloth. However, the industrial revolution supplied the Indian industry with weaving and spinning machines that increased cotton production.

The industrialization on Indian ground that was introduced in the XIX century flooded the country’s territory with numerous cotton mills. In the context of international market competition, the British Empire tried to expand the industry as much as it was possible. The industrial revolution brought technological innovations to India. For example, Bombay cotton mills were equipped with the products of the Platt brothers that affected the development of the Indian economy and improved cotton production. Indian textile machinery manufacture could be a serious rival to other metropolitan industries. Unfortunately, this innovation in cotton textile was not directed to the overall growth of the country’s economy, but to the enrichment of the British who exploited Indian cheap labor.

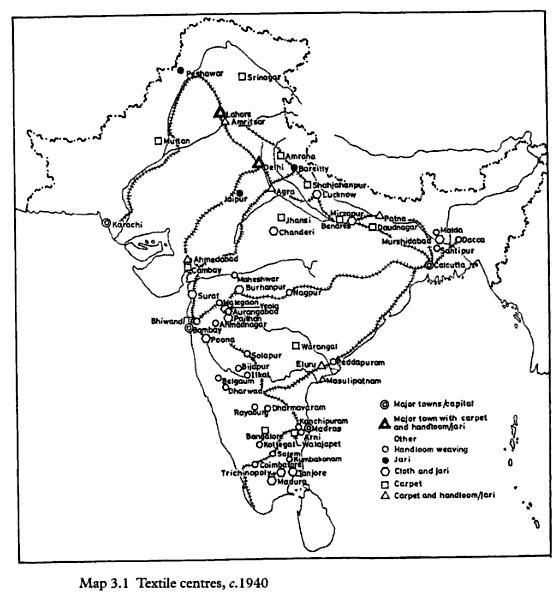

The investment of Britain in the development of textile manufacturing was a valuable contribution to the Indian future industrial success. The geographical position of India allowed taking advantage of sea trade roots. “Cotton roads” investment yielded fruits: the golden period for British exports was in 1860-1914. Proceeding from Chandavarkar’s book, one may agree with the author’s following statement: “cotton textiles constituted India’s most important industry and in conventional terms formed the lead sector of the economy”. Figure 11 (see Appendices, fig. 11) shows Indian textile centers at the end of the period of the British raj. One may see the diversity of the Indian economy that was realized in British artificial industrial expansion through textile centers all over the country. Thus, it was the key to the British Empire’s industrial success and domination in the world trade that promised to enrich the British economy using Indian natural and human resources.

As the railway network of India took an active part in trade, certain Indian provinces became the center of the cotton textile industry (for example, the province of Maharashtra with the capital in Bombay). The market expansion developed the domestic market and improved inter-city trade: for example, Gujarat sold its cotton products to Delhi. According to Williamson (2008), “per capita consumption of cotton textiles in 1920 was about 11.65 yards”. It explains the success of British exports to the Indian market. In the context of agricultural exports, raw cotton production was an essential industrial intermediate that enriched the British Empire.

Gradually, there appeared Indian textile cotton producers (for example, the House of Narang); they were promoted by the British textile manufacturing firms. They provided the British Empire with large profits. For this reason, they were specially protected and financed. For example, it created a suitable condition for Coimbatore that soon became one of the largest cotton textile centers. However, Williamson noted the notable decline in yarn used for handloom products: “from 419 million pounds in 1850 to 240 in 1870 and 221 in 1900”.

There are three phases of development of the Indian cotton industry. The first phase of expansion of the cotton industry was in the 1870-the 1880s. The success of this period was conditioned by the penetration of the Chinese market, where India became the main producer and exporter of raw cotton (low-count yarn). The next phase was at the turn of the centuries and was characterized by the competition in the local market between Bombay and Ahmedabad that supplied the Indian spinning mills with yarn. The third phase occurred in the 1930s when multiple Bombay mills were closed down for the reason of old equipment. At that time, there was the crisis of Indian industry (economic depression, difficult inter-war period) that decreased the cotton production and affected negatively speculative mill owners.

In 1930, it was evident that the Japanese market speeded up the process of Indian devolution in the economy. Gradually, the British Empire began to lose the economic position in the Indian market, as the Indian import of cotton goods from Japan prevailed over the import from Britain. However, primarily, Indian local factory production declined British export.

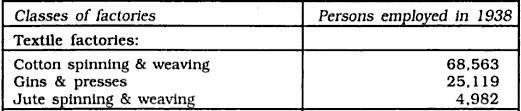

The cotton textile industry provided the Indian population with employment. The number of workforce in 1928s was about 150,000, in 1938s – almost 200,000. According to some data (see Appendicitis, fig. 10), during the Madras presidency, there were employed almost 70,000 in such textile industrial branch as cotton spinning and weaving factories. Nevertheless, the exploitation of cheap Indian labor was evident; even children were involved in manufacturing. Natural and human resources increased the number of industrial centers.

In comparison to the UK, till 1929, India had a sufficient level of labor productivity performance (nearly 15 % of the UK’s level). However, later, the Indian industry became to decline, and could not catch up with the UK’s industrial development. Indian industrial output shows certain fluctuations in the period of British raj; nevertheless, in terms of labor productivity, the industrial sector was more successful than the agricultural one. Unfortunately, by the end of the British Raj, India’s level of production of cotton for agriculture and industry was extremely low. It may be explained by the low prices of cotton on the internal market. Thus, there are negative visible changes in the field of Indian cotton textile. The colonial status did not create suitable conditions for the industrial development of the Indian economy.

Agricultural Reforms

Agriculture became the source of the Indian economy. Efficiency and productivity of Indian agriculture, under the British raj, can be explained by the progress, encouraged by the British government. The policy in the agricultural sphere may be seen through the light of agricultural reforms.

Indian agriculture was one of the economic diamonds that fed the industries and market of the British Empire. Primarily, British traders, planters, and manufacturers benefited from commercialization. Nevertheless, the Indian population suffered from it. Gradually, this policy led to a horrible phenomenon for the agricultural economy: large food crop area was declined, as commercial crops exhausted Indian soil. The situation worsened: the Indian population grew in size, and the internal consumption increased. Indian villages were not self-sufficient anymore. As the local prices for agricultural products were linked with those of the world market, farmers increased their income using price improvement.

The commercialization of the country’s agriculture was realized through the class of moneylenders, whose dominance increased. They exploited peasants to get large profits; many peasants lived in debt. The class of Indian moneylenders was encouraged by the British government because they contributed to the country’s revenue. Jayapalan considers moneylenders as “the instruments of colonial exploitation of India”.

During the period of the British raj, the commercialization policy in the agricultural sphere was evident, as everything was directed to profit. In this context, the British government relied on local zamindars (land tax collectors). However, for most of the Indian peasants, it was impossible to pay high taxes; the population lived in poverty, debts, and famine.

In the 70s of XIX century, the governmental policy was directed to “the encouragement of agriculture, the exploitation of mineral wealth and diffusion of industrial knowledge”. In the context of the industrial revolution, Indian agriculture faced technological innovations. “Staple industry” was stimulated with the products of industrialization. Machines and special equipment, imported from the British Empire, speeded up the agricultural process. Steamers served not only for the needs of agriculture but for manufacturers, mining, navigation, etc.

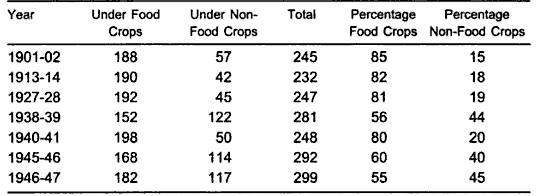

Even though the Indian population increased, the agricultural policy met the demand of world trade. Many Indian crops were exported. For example, figure 12 (see appendices, fig. 12) shows that the most profitable period for Indian crop export was in the 1920s. The export of jute products was equal to 493 million rupees, rice – 309, tea – 260, raw jute – 255, etc. Indian agricultural production was based on food crops (for consumption) and non-food crops (for commercial purposes and industries). Figure 13 (see appendicitis, fig. 13) shows the territory, where food and non-food crops were cultivated. As one may see, during 1901- 1947, the territory under food crops was larger. The reason lies in the fact that there was considerable consumption of crops by the increasing Indian population. Besides, a certain portion was exported. Moreover, the war-times (two World Wars) dictated the necessity of food. For example, the table shows that in 1940-1941, 198 million acres were under food crops; in contrast to it, only 50 million acres were under non-food crops. Thus, in this context, the British policy adjusted the Indian economy to the world demand.

However, commercialization had a positive effect on Indian agriculture. The large territory of India was cultivated; the area expanded, as more and more cash crops were planted. This way, there appeared to the specialization of certain agricultural zones in India. The South of India was suited for sugar cane; in Assam, tea was cultivated; Punjab was suitable for wheat; jute was cultivated in Bengal; the territory of Khandesh and Berar helped to cultivate cotton, etc. Besides, the Indian agricultural market was widened, as there were introduced new crops: coffee, groundnut, tea, potato, oilseeds, some fruits, and other crops. They were exported via land and sea. Moreover, the railroad network contributed to the expansion of agricultural products.

In the context of the commercialization of agriculture, the rural industry was stimulated. At the same time, agriculture was partially combined with weaving. Some provinces produced “general wear of the laborer and small farmer”, made of coarse cloth. However, this experiment was not successful in conditions of the crises of 1910 and Indian cloth tradition.

Besides, the conditions of the Great Depression made the British government implement deflationary monetary policy and a high-exchange rate. This policy was duel because Indian peasants suffered, and the others derived profit from it. The period of 1920s-1930s can be considered as the period of stagnation for Indian agriculture. Bad harvest led to a price increase that negatively affected the local population.

Gradually, the Indian workforce shifted away from agriculture (such states as madras, Kerala, West Bengal, Maharashtra, etc). Of course, this tendency affected agriculture negatively. Employment opportunities were more notable in the industrial and service sphere (better working conditions, wage, etc.). Consequently, the agricultural reforms influenced Indian traditional agriculture more negatively than positively: the Indians turned to the debtors.

Conclusion

All mentioned above allows making some general conclusions about the problem under research. The period of the British raj (1857-1947) was one of the essential periods in Indian economic history. This period turned India into a British colony that served to feed the British Empire’s market, industry, and population. Capitalistic policy on Indian ground had its peculiarities. In general, the effect on the Indian economy was both positive and negative. Thus, the impact of British colonialism on the Indian economy is a rather ambiguous problem to be investigated.

The colonial time changed the face of India that gradually transformed from a country with a traditional economy to a country of world importance in terms of international trade. As most of the textile and agricultural products were exported, India was flooded with British goods. The size of export was larger than that of import. The success of the Indian market in the context of international trade lies in its competitive ability: for many years, the British-Indian trade pushed other countries off from the world market.

Social life changed, as well. Under the British raj, India faced millions of British immigrants, who came to India to live and consider themselves at home in an exotic country. Primarily, they pursued their interests and purposes: to enrich themselves and take advantage of the hard labor of the local population. However, social policy improved Indian education, healthcare, abolished inhumane traditions in the culture and brought relative stability. Nevertheless, the Indian population was exhausted with unfair British policy that froze the development of the country’s economy and made it retarded. Gradually, the national self-consciousness of the Indians put them on the way to national self-identification and liberty.

The cotton textile industry and agricultural sector benefited from the industrial revolution. Machines, steamers, railways, telegraphs, roads, bridges, and other advantages of technological industrialization improved India to a certain extent. However, a predatory land tax collection system, high prices on the local markets, overall economic devolution worsened the condition of the Indian population.

In this context, one may suggest a logical counterfactual connected with the possible future of India as the Mughal Empire. However, the discussed researchers’ results prove that India has hardly been better off if the Mughal Empire had survived. The empire played a significant role in the period of East-Indian Company that positively influenced its economy. Nevertheless, if India had not experienced the British raj, it would not take advantage of the products of the industrial revolution that developed the economic potential to the great extent. However, it is a rather controversial counterfactual. The dual effect of the British raj affected Indian political, economic, social, and cultural life.

Taking into consideration all discussed researcher’s results and analyzed economic indices, some key positive and negative factors of the British raj’s policy in the Indian economy can be mentioned. Positive features of economic changes and reforms were the following: industrial centers speeded up the process of overall economic and technologic development (mostly, because of the industrial revolution), and gave also employment for the Indian population; the Indian agriculture and market were widened with the assortment of crops; the cultivated territory expanded; cotton textile industry was invested and improved. Nevertheless, negative ones were also notable: the British raj declined put aside certain traditional industries of India, practiced in villages; there was unlimited exploitation of natural and human resources that had an exhausting effect on Indian economy; often, peasants suffered from famine and poverty; imported British goods on the Indian market practically eliminated Indian products; the stationary bandit’s economy did not meet the demands of traditional Indian economy, and artificially constrained its development. Proceeding from the conclusion, one may agree that the period of the British raj affected the Indian economy differently; the analyzed situation in textile and agricultural industries proves the dual effect of the British policy.

References

A. Banerjee, & L. Iyer, ‘Colonial land tenure, electoral competition and public goods in India’. Web.

S. Bhattacharya, The Financial Foundations of the British Raj: Ideas and Interests in the Reconstruction of Indian Public Finance 1858-1872 (New Delhi, India: Orient Blackswan, 2005).

‘British imperialism in India’, n. d. Web.

S. Broadberry, & B. Gupta, ‘The Historical Roots of India’s Service-led Development: a Sectoral Analysis of Anglo-Indian Productivity Differences, 1870-2000’ Warwick Economic Research Paper, 185 (2007).

L.J. Butler, Industrialization and the British Colonial State (London, UK: Routledge, 1997).

P.J. Cain, & A.G. Hopkin, British Imperialism, 1688-2000 (Harlow, UK: Pearson Education, 2002).

R. Chandavarkar, Imperial Power and Popular Politics: class, Resistance and the State in India, c. 1850-1950 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

J.B. Das Gupte, Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy, and Culture. Sub Project: Consciousness, Science, Society, Value, and Yoga, & Centre for Studies in Civilizations (Delhi, India), Science, Technology, Imperialism and War (Delhi, India: Pearson Education India, 2007).

W.J. Duiker, & J.J. Spielvogel, The high tide of Imperialism. In L. Ciccolo (Ed.), World History (6th ed.) (Vol. 2, pp. 618-642) (Boston, MA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, 2008).

‘Historical maps of India’ (2011), Regional maps: India, 1857. Web.

“Historical maps of India’ (2011), Regional maps: India, 1893. Web.

J.A. Hobson, Imperialism: a Study (New York, NY: Cosimo, 2005).

‘India as colony: 1850 to 1947’, Hinduism Today (2010). Web.

L.S. Iyer, Direct Versus Indirect Colonial Rule in India: Long-term Consequences (2008). Web.

N. Jayapalan, Economic History of India (New Delhi, India: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, 2008).

A. Kohli, The Success of India’s Democracy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

H. Kulke, & D. Rothermund, A History of India (Abington, UK: Routledge, 2004).

D. Kumar, T. Rauchaudhuri, & M. Desai, The Cambridge Economic History of India (Vol. 2) (Cambridge, UK: CUP Archive, 1983).

A. Maddison, ‘The economic and social impact of colonial rule in India. In Class Structure and Economic Growth: India & Pakistan since the Moghuls’ (London, UK: Allen and Unwin, 1971). Web.

‘Mohandas Gandhi (1869-1948): major events in the life of a revolutionary leader’, n. d. Web.

S. Mukherjee & J. Chakrabarti, Evolution of Indian Economy & Elementary Statistics (New Delhi, India: Allied Publishers, 2000).

M.E. Page, & P.M. Sonnenburg, Colonialism: an international social, cultural and political encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2003).

K.V. Reddy, Class, Colonialism and Nationalism: Madras presidency, 1928-1939 (New Delhi, India: Mittal Publications, 2002).

D. Rothermund, An economic History of India: from Pre-colonial Times to 1991 (London, UK: Routledge, 1993).

T. Roy, The Economic History of India, 1857-1947 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006).

T. Roy, Traditional Industry in the Economy of Colonial India (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

B.R. Tomlinson, ‘Stages of capital: law, culture, and market governance in late colonial India’ Business History Review, 84 (2010). Web.

B.R. Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, 1860-1970 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

D. Tripathi, ‘Colonialism and technology choices in India: a historical overview’ The Developing Economies, XXXIV-1, 80-96 (1996).

M. Olson, Power and Prosperity: Outgrowing communist and capitalist dictatorship (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2000).

C. Watterson, ‘The Keys to British Success in South Asia’ (1985). Web.

J.G. Williamson, ‘Globalization and the Great Divergence: Was Indian Deindustrialization after 1750 Different?’ (2008). Web.

Appendices

Fig. 9. World manufacturing output (1750-1939). Source: J.G. Williamson, ‘Globalization and the Great Divergence: Was Indian Deindustrialization after 1750 Different?’ (2008) .