State-of-the-art of the UK startup market

Recent historical market trends for startups in the UK

In spite of the ongoing global financial turmoil and economic challenges faced by Europe, for years, the business environment of the United Kingdom remained not only stable but also positive, forward-looking and open for business. For the last few decades, the UK government has shown commitment to supporting new businesses, which accounted for a private-sector-led economic recovery. As of now, the UK is the world’s sixth-biggest economy and ranks high among the world’s top manufacturers (OECD, 2019).

Among other metrics, it is worth a mention that the UK ranks second among the world’s largest services exporter, with the US being the absolute leader. Besides, the Western European country is the world’s sixth-largest trading nation (OECD, 2019).

The ease of doing business is what makes the UK the most attractive place in Europe for overseas companies to base their headquarters. Statistically, the UK has more European headquarters than France and Germany combined. As for starting new businesses, the UK is recognised as the best place to set up and run a business in Europe. As stated in a report by the World Bank, on average, it takes 13 days to start a company as compared to the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development) average of 15 days. Amid the European countries, this metric has yet to be outperformed.

Among the most fargoing initiatives by the UK government is the introduction of the startup visa in 2011. The new type of visa served as a replacement for the Tier 1 Graduate Entrepreneur visa program. To attract foreign startupers, the UK expanded the eligibility criteria beyond the EU, the European Economic Area and Switzerland. The visa applies to those who would like to set up a business in the UK that has the potential of being endorsed by an authorised body. The latter may include a UK higher education institution or a business organisation with a history of supporting UK entrepreneurs (House of Commons Library, 2018). The startup visa is reserved for business in early stages and unlike the Innovation visa, does not require investments.

Due to the aforementioned changes in legislation and economic ties, each year, the UK seems to be witnessing one record after another. For instance, between 2015 and 2017, the number of new, UK-based businesses has risen from 608,000 to 660,000, proving that the West European country remained unrivaled as a place for starting a company. Moreover, disruptive startups has become the key for the rapid economic growth (House of Commons Library, 2018).

The nature of disruption is introducing a product or a service that sets a new bar for the entire field and compels other industries to keep up – or be left behind. In the case of the UK, it has already seen such products whose founders chose this particular country for their headquarters. Last.fm and its more well-known successor, Spotify, has changed the world of online music streaming.

The new milestone that the UK is now attempting to pass is to encourage more students and recent graduates to start businesses. As per most recent statistics, each year, disruptive startups contribute as much as 196 billion pounds to the UK economy. Yet, only 5% of university students and graduates to pursue the entrepreneurial path (House of Commons Library, 2018). The government acknowledges that more often than not, young people give up on a dream of having their own businesses due to the overwhelming need to find financial stability.

It is argued that new startups are being held back at the seed stage due to the lack of funding sources. At that, traditional funding methods seem not to be making the cut. Thus, the overall trend on the UK startup market is a search for new, innovative funding models. As of now, the government intends to test on-campus funding that would allow students to receive business loans on behalf of the government. The program is now operating in several universities across the UK. Another viable alternative that has been gaining popularity is crowdfunding and crowdsourcing. Lastly, young startupers many of whom are not done with their studies yet choose Lean Startup model. They aim at creating an MVP – minimum viable product – to attract the first customers and establish a customer base.

Experts from a large tech startups, SeedLegals, have outlined some more startup trends that are bound to shape the market in the years to come. First, UK startups no longer need to accumulate a large amount of money in investments and/ or group investors in order to be launched. Instead, the trend is that businesses fundraise continuously from their existing professional network even though it means receiving smaller sums of money each time.

Further, the UK is witnessing an evolution in startup advising. Namely, receiving business and legal recommendations is no longer limited to specific institutions that require application and approval. Knowledge regarding startups becomes democratised and available online. Lastly, as SeedLegals report, deal terms benefit founders more than ever while previously, investors had the last say in the game.

Main growth drivers and enablers

One of the main growth drivers in the region is probably the capital of the country itself that gained international recognition as a thriving business center. Numbers and figures speak louder than words: for instance, according to recent statistics, in 2018, in London, there were 1,563 businesses per 10,000 resident adults. This is 50% more than the national average of 1,059 businesses per 10,000 resident adults. As of now, every third UK-based business is located in London or the South East region in general (to be more precise, 1.1 million in London and 874,000 in the South East).

Today, London boasts a comprehensive network of tech clusters, business hubs and incubators. It may be argued that the challenges involved with moving to the United States, the classical business destination, to start a company as an immigrant has sparked the boost of incubator programs in the EU. A prime example would be Seedcamp that runs its programs across Europe and hosts its largest event in London where the organisation itself is currently based.

The importance of London was recognised by the UK Trade and Investment that makes part of the British government. In 2011, in an attempt to encourage a healthier, more robust business ecosystem, the institution established the Tech City Investment Organisation, previously known as Tech City, East London’s growing tech cluster. Since then, the government has involved a number of high-profile companies such as Cisco, Intel and Google by providing incentive to base their headquarters there. Another meaningful piece of statistics shows off the success of the initiative states that the number of high-tech companies based in the Tech City has risen from 15 in 2008 to 500 in 2018.

Another great enabler of growth in the region is the diversification of the economy. Since the 1970s onward, the UK economy has been successfully transitioning to a service based economy characterised by a steady decline of the traditional manufacturing base. As of 2019, the greatest share of the UK’s wealth is derived from the financial sector. While there are still the remnants of manufacturing and heavy industry, the value from these sectors is barely comparable to the value derived from the services sector. Besides, the government itself expresses a clear commitment to building a so-called knowledge based economy – the type of economy driven by science and innovation. Today, the UK does not shy away from investing into scientific fields with wider benefits and higher risks.

The diversification of the economy and its focus on the global trends means that up and coming startups as well as entrepreneurial-minded immigrants have enough space to find their niche. For years now, the UK has been capitalising on the so-called green economy and environmentally-friendly solutions. For instance, the UK has become a leading global player in wind energy and has pursued an ambitious agenda in the development of offshore wind. The country’s interest in sustainability makes supporting “green” startups mutually beneficial. While the UK provides founders with a platform for growth, it also takes advantage of the new technology and initiatives.

Other trends on the UK startup market include a new successful business model – subscription. This model is quite straightforward: buyers can receive any product or service delivered to them as often as they please, which ultimately puts them in control. Apart from that, it is observed that many startups build AI-based business models. While big corporations may suffer from rigid structures not exactly allowing to implement machine learning and artificial intelligence methods, startups have more flexibility and space for risk-taking and testing. Lastly, the UK is likely to remain big on cryptocurrencies. As of 2017, the West European country had had a lead on cryptocurrency exchanges while mining, on the other hand, is focused between China and the United States.

Economic and financial regulations in the UK

It is argued that the UK owes its startup revolution that started less than a decade ago to a series of well thought-out governmental regulations that took part between 2010 and 2015. In 2010, the global financial crisis was in its last stage; the same year, David Cameron came into office and expressed an intention to cut down on red tape and reckless spending. Cameron’s commitment to making a change found a reflection in the 2010 Coalition agreement whose pillars were proclaimed to be freedom, fairness and responsibility. The government recognised business as the main driver of economic prosperity and innovation. Thus, it was seen as imperative to boost enterprise by easing regulations and allowing new businesses to emerge and grow. The following was agreed upon by both parties:

- “One-in one-out” principle: no regulation shall be introduced without limiting the power of another regulation, therefore, cutting down red tape and keeping the system transparent and as uncomplicated as possible;

- “Sunset clauses”: each regulation is reviewed for relevance;

- Creating the most competitive corporate tax regime in the G20. This entails simplifying reliefs and allowances to tackle avoidance and reduce headline rates. At that, the government expressed commitment to protecting manufacturing industries;

- Considering the public’s opinions: citizens were given the right to challenge the worst business regulations;

- Reviewing employment laws to increase flexibility in the workplace, while ensuring fairness and transparency of work relationships;

- Moving toward the “one-click” registration mode: enhancing the ease of doing business by reducing the number of procedures and the overall duration of setting a new business. The end goal was to outperform other countries in the region and even globally, making the UK the most attractive platform for running a company or locating headquarters;

- Repealing the ban on social tenants starting businesses in their own homes;

- Implementing the Dyson review: refocusing the research and development tax credit on hi-tech companies, startups and small businesses. If implemented properly, that measure would contribute to making the UK the world’s top exporter of hi-tech products (HM Government, 2010).

The 2010-2015 business policies were characterised by the search for meaningful alternatives to governmental regulations that were often found intruding and impeding. The government stated that regulation would be a last resort when all other measures had failed. The following ideas were considered and implemented fully or in part:

- Using existing regulation;

- Simplifying or clarifying existing regulation;

- Ensuring the proper enforcement of existing regulation;

- Enhancing accessibility of legal remedies;

- Total inaction if appropriate.

Overall, authorities argued that intricate and harsh regulations strip entrepreneurs, businesses and customers of self-agency. Well-informed decisions by both parties (sellers and buyers) are only possible on the premise of information availability and education. For instance, customers could consult independent sources for recommendations, ratings and labelling. Apart from financial literacy, self-regulation, ownership and accountability could boost enterprise.

The government suggested that new businesses adopt their own codes of practice and promote ethical conduct. Co-regulation has some similarities with self-regulation but in this case, the government is involved to a certain extent. Authorities do not impose any decisions on an industry; instead, they might work together to develop a code of practice. Since organisations and professionals within an industry know their trade inside-out, they have a clearer picture of what needs to be done to make work processes more efficient.

Apart from the aforementioned measures, the UK government employs a variety of economic instruments to make sure that the business environment prospers and stays welcoming for new entities. Authorities affect their behavior by constantly changing and improving:

- Taxation and subsidies (ex.: Research and Development Relief for Corporation Tax);

- Quotas and permits (ex.: the European Union trading scheme for carbon dioxide emissions from electricity generation and the main energy-intensive industries;

- Competition by businesses from all industries.

What is special about business regulations in the UK is that they do not only exist on paper. It is quite the opposite – through years of careful reinforcement, they seem to have yielded practical results. One of the most comprehensive rankings, Doing Business, takes into account many indicators to determine whether a particular country is a good place to start a business. For years, the UK has been showing consistently good results. In 2019, the UK ranked 9th out of 167 countries assessed (World Bank Group, 2019a). As compared to the country’s main competitors for the top of the list, the UK scored slightly less than the US (ranks 8th).

At the same time, the UK scored much better than its most powerful European neighbors. For the sake of comparison: in 2019, Germany, the strongest EU economy, only came 24th; Ireland ranked 23d and France ranked 27th. On a scale from 0 to 100 where 100 is an outstanding ease of doing business, the UK has scored 82.65 and by that, surpassed the regional average of 77.80.

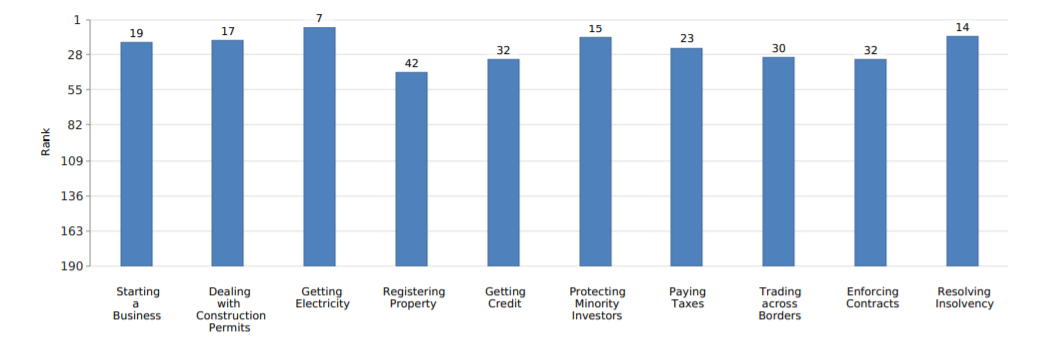

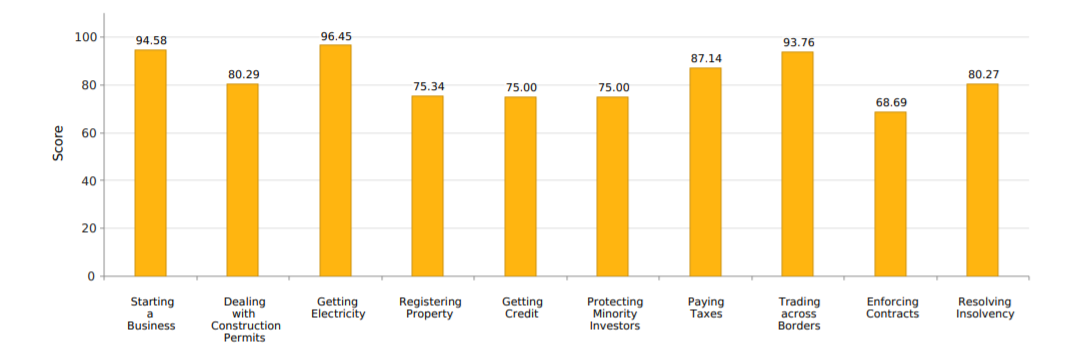

As seen from Figure 1, the UK ranks differently across the various business topics analyzed by experts. So far, the UK shows the best relative results in providing businesses with electricity (7th), helping to resolve insolvency (13d), giving construction permits (17th) and starting a business (19th) (World Bank Group, 2019b). When it comes to absolute scores, the UK boasts the following outstanding metrics: starting a business – 95.58, getting electricity – 96.45 and trading across borders – 93.76. However, it would be more compelling for us to contrast these metrics to those that were obtained pre-Brexit to see whether the UK has actually somewhat lost its standing.

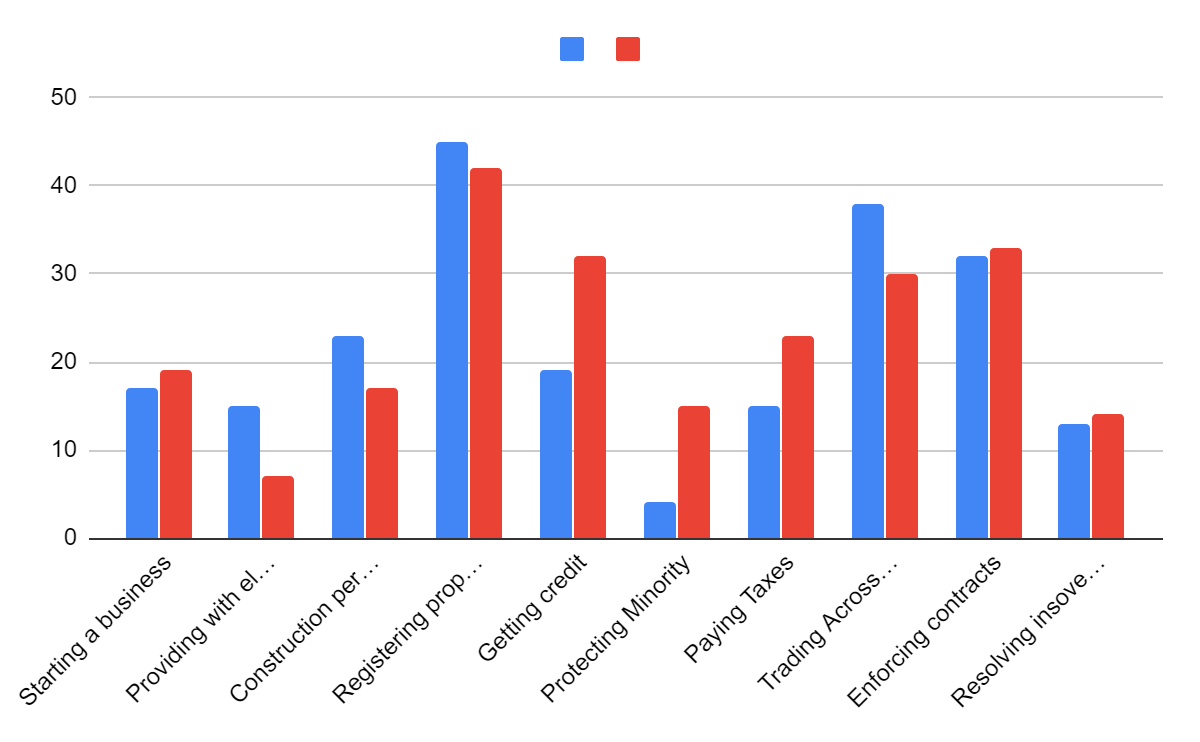

As seen from Figure 3, pre-Brexit Britain seemed to be providing better conditions for starting a new business (17th to 19th) (World Bank Group, 2016). The UK appears to have made major improvements in providing electricity.

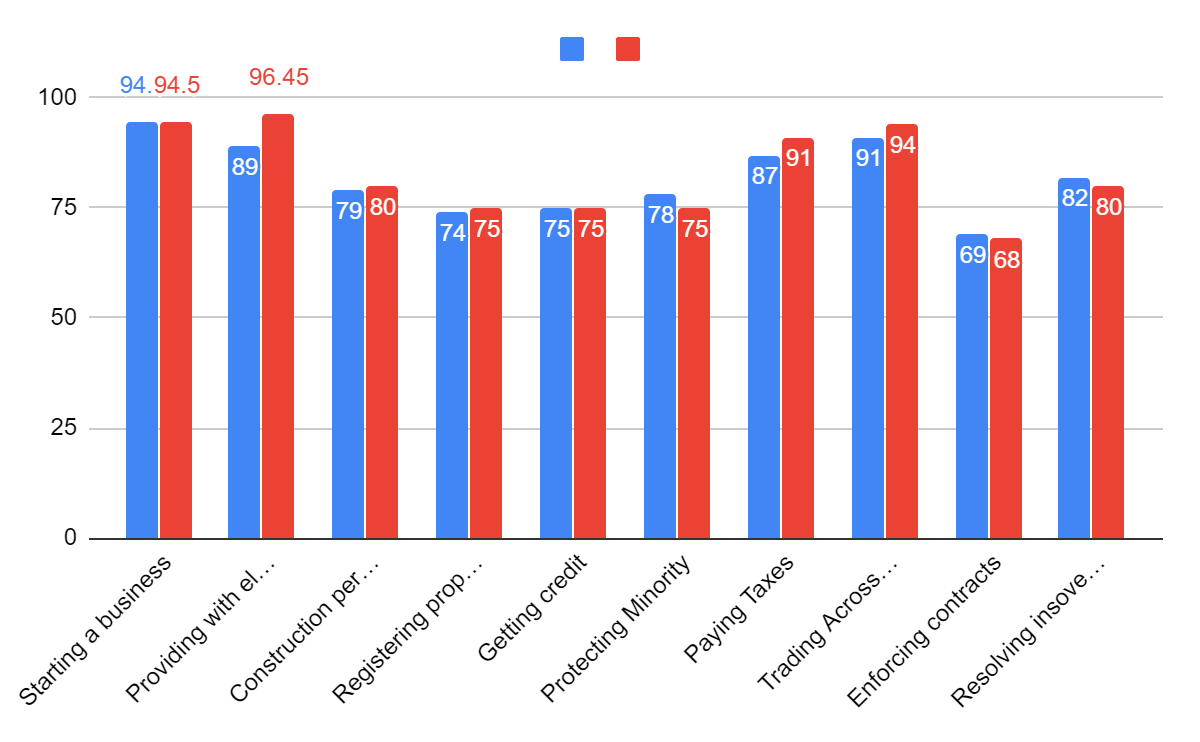

Registering business property has become slightly better by 2019. The metrics that are to temper optimism include protecting minority investors, paying taxes and getting credit. Strangely enough, ongoing Brexit negotiations have not yet had a negative effect on the Trading Across Borders metric – instead, by 2019, the UK has made slight but tangible progress. What is interesting though is that when we look at Figure 4, we can conclude that some of the objective scores have not changed much. For instance, even though the UK scored 78 for protecting minority investors in 2017 vs 75 in 2019, it has lost 11 positions. This may be attributed to other countries making better moves while the UK sticks to its established regulations.

Fintech/ neobank sector

For the last few decades, the UK has been at the forefront of the financial services revolution. Statistically, the nation’s fintech industry contributes around 20 billion pounds to the budget in annual returns. Since 2016, Business Insider has been stating that FinTech in the UK could be bigger than ATMs, PayPal and Bitcoin together. A telling example is that while 2017 was not the best year for Bitcoin, Fintech businesses were exceptionally resilient to recession.

In 2017 alone, the country’s Fintech sector attracted approximately 1.3 billion pounds of funding (McIntyre, 2019). Fintech startups owe their success to bringing disruption to the classic banking business models. Fintech industry has been using technology to provide people and businesses with comprehensive tools for managing finances and making transactions and investments. These startups now can stand competition with established brands and lead the change in the entire industry.

In January 2018, the UK introduced open banking reforms so that the banks could provide their data to third parties. The legislation requires banks to allow their customers to share their transaction data through so-called APIs (application programming interfaces). Open banking lets customers reap the benefits of ever-emerging innovations and drives more competition in the sector that has been long dominated by a few big names. Besides, as FinTech thrives, it reduces the need for physical branches. It is projected that consumer visits to branches will drop by one-third between 2017 and 2022 (McIntyre, 2019). At the same time, mobile transactions will experience a rapid increase of 121% in the same time period.

Banking apps are as sophisticated as ever, allowing customers to make instant transactions, create new accounts, freeze lost and stolen cards as well as replacing old ones. Together with a wider use of machine learning, natural language processing and artificial intelligence, it is likely that customers will be talking to businesses using chatbots as opposed to contacting call centers or physical branches. One more trend is the introduction of biometrics as passwords and pin codes are becoming obsolete. As financial data is becoming as precious as ever, biometrics can become a new frontier in data security.

The rapid rise of FinTech in the UK seems to be attracting foreign workers. According to recent statistics, almost half of employees in the FinTech sector (42%) are from overseas. Digital tech companies in London are the most connected in Europe, second only to Silicon Valley for international connections. 25% of entrepreneurs across the world report having a significant relationship with two or more entrepreneurs in London, compared to 33% for Silicon Valley (McIntyre, 2019).

All these advancements have made the UK the most disrupted traditional banking market in the world. As of 2019, as much as 15% of revenue and over 30% of new revenue is generated by new entrants to the banking sector. What drives the emergence of new players is the combination of eroded trust in traditional systems and governmental regulations that stimulate competition. Some of the new financial institutions that have emerged as a result of these ongoing trends are Monzo, Starling, N26, Revolut and Marcus from Goldman.

For now, Brits are cautious of the new companies in the banking sector. For instance, less than 20% of their customers use their services as their primary checking. However, it is projected that given the growing popularity of the new entrants in the field of fintech, more people are going to switch to this option. Of course, these dynamics did not go unnoticed, and a timely reaction of the entrenched UK banks ensued.

As of now, they are trying to launch their own digital challenges (example: RSB must have six in progress) and upgrade their key digital services. It will soon become clear whether big companies with often more rigid structures but at the same time more resources are able to respond to the intrusion. The opposite scenario looks equally possible: in the upcoming year, the new entrants may as well gain enough momentum to yield positive long-term perspectives.

All in all, the future prospects for fintech in the UK seem bright and promising. The country is at the turning point between theorising and putting new solutions to practice. The UK is likely to further develop open banking, consumer-centric applications and new payment form factors. Yet, recent political events such as Brexit raise the question as to whether the UK will remain the same friendly environment for foreign entrepreneurs.

Investment in the UK

Financial Sector: Statistical Overview

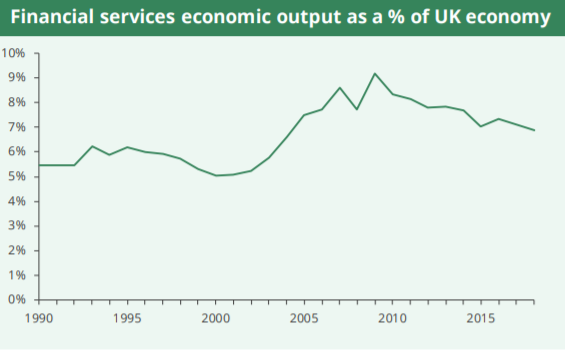

In 2018 alone, the financial services sector made a contribution estimated at 132 billion pounds to the UK economy, which accounted for 6.9% of total economic output (Figure 5) (House of Commons Library, 2019b). At that, London generated almost half of the output – around 49%. As compared to other countries, the UK financial services sector ranked seventh among the OECD countries on the criterion of its proportion to national economic output.

Luxembourg became the leader with a share of 26% of national economic output attributed to the financial services sector. The described sector created many jobs whose number had amounted to 1.1 million, or 3% of all jobs, by 2018. The economic excellence is reflected in the statistics on the export and the import of financial services – 60 billion pounds and 15 billion pounds respectively. 43% of financial services were exported to the EU, and 34$ of financial services were imported from the EU. In tax, the sector made a major contribution of 29 billion pounds.

Despite these seemingly good statistics, there is still a lot that is unsettling about the current situation. The intention to leave the EU presents many challenges for the financial services sector. Before the UK voted to leave the EU, European businesses enjoyed their membership of the Single Market. Any financial business authorised in any Member State could conduct its operations freely within the European Economic Area (EEA). This policy known as passporting reflected the EU’s political vision for economic growth. It was also in line with the UK government’s intentions to make the UK business environment a friendlier place for foreign entrepreneurs and investors.

Unfortunately, the logic of Brexit compromises this common foundation. Since the UK has confirmed its decision to leave the Single Market, the EU responded with ruling out the passporting policy. This means that the existing benefits cannot be maintained (House of Commons Library, 2019a). As of now, the UK claims to be developing equivalent policies that would leave the procedure of taking one’s business to the UK intact.

Theoretically, it is a sound and reasonable decision, and yet, in practice, the process is likely to be excruciatingly slow and subject to political considerations. Moreover, the UK will gain full autonomy on managing the equivalence policies, meaning that it can review or cancel them unilaterally. It does not appear exactly attractive as it creates uncertainty for foreign businesses (House of Commons Library, 2019a). Probably, one of the ways to evaluate how “healthy” the current business environment is in the light of recent events is to analyze investment trends and opportunities.

Investment in the UK: Statistical Overview

As of 2019, Brits seem to be big on investment: the number of people who give it a go seems to be much larger than expected. As many as two million people have invested money in stocks and shares. 12.4% of UK shares are bought and owned by individuals with almost half of them (43%) being women (Finder, 2019). Some other quick facts that could help to paint the full picture of the UK investment environment are the following. The total value of all stocks traded across the globe is estimated at $68.212 trillion. As compared to these metrics, the London Stock Exchange (LSE) is estimated at 5% of the global value (the total of $3.76 trillion). Below is a breakdown of who owns UK shares and what percentage of them precisely (see Table 1):

Table 1. UK share owners.

Despite the piece of statistics above showing clear interest of foreign companies and individuals in owning UK shares, other metrics may temper the optimism. One of the key metrics that help to understand the situation is Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). It is defined as the amount of money that UK individuals or businesses have invested in other countries (outward) or other countries have invested in the UK (inward).

As it turned out, as of 2019, outward FDI has been at an all time high and totaled 91.4 billion pounds. The UK companies and individuals have invested the most money in the US. At the same time, the UK has lost some attractiveness for foreign investors. Inward FDI fell from 192 billion pounds in 2016 (pre-Brexit) to disastrous 92.4 billion pounds. The greatest investor is Japan: it invested as much as 29% of the total value of inward FDI, or 27.1 billion pounds (Finder, 2019). At that, what could be telling for us and help us to analyze the situation further is the dynamics in the investment banking sector.

Investment Banking

Investment banking is defined as a subdivision of a bank or a financial institution that serves governments, corporations and institutions by providing advisory services on underwriting (capital raising) and mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Basically, investment banks are the key mediators between investors and corporations – the former have money to invest, and the latter need funding to realise their projects and run their businesses. The UK traditionally had a strong investment banking sector, and yet, recent political events must have shaken the grounds and made it lose its standing.

By 2019, US investment banks dominated the rankings in the UK. At the same time native UK and European banks have shrinking market shares and staggering revenues. Experts emphasise how Brexit has weighed on deal making resulting in a 36% decrease in investment banking revenues as compared to the same period in 2018 (Clarke, 2019). Internationally, the only European bank that solidified its place among the top five is Barclays. The UK has always been central to Barclays’ transatlantic investment operations that were given a strong head start in 2015 (Clarke, 2019). For the first few years, the strategy was working out well, allowing the bank to gain more market share. However, in the first half of 2018, following Brexit negotiations, Barclays lost $135 millions and lost its standing.

When it comes to mergers and acquisitions, the UK is also showing results that are from optimistic. The total value of announced M&A in the UK has decreased by 66% even though the average decline across Europe, the Middle East and Africa is estimated at 34%. Globally, UK investment banks continue to lose competition to their Wall Street contenders. So far in 2019, European investment banks have received 25.3% of fees – an all-time low – while their US counterparts have pulled in 52.7% of revenues.

Yet, some argue that the UK has yet to make big moves to amend the situation. Positive changes could come from collaboration instead of competition. For instance, US-based Jefferies has shown good growth dynamics by jumping from the 25th place in 2018 to the ninth in 2019. The US investment bank has been building a strong UK and making significant investments in its European business, including in the UK.

Startup Funding in the UK

Traditionally, there were plenty of opportunities to receive funding for a startup in the UK. The most popular forms of funding included the following:

- IPO stands for an initial public offering (IPO), a process in which shares of a private corporation are offered to the public in a new stock issuance;

- VC, or venture capital, is a type of private equity, a form of financing that is provided by firms or funds to small, early-stage, emerging firms that are deemed to have high growth potential, or which have demonstrated high growth (in terms of number of employees, annual revenue, or both);

- Angel investment is an investment by a wealthy individual in support of a new startup, usually in its early stages;

- Private placement is a funding round of securities which are sold not through a public offering, but rather through a private offering, mostly to a small number of chosen investors.

Yet, in the light of recent political events, the UK vivid startup scene can be in danger. One of the reasons for that is the possibility of “no-deal” Brexit is very much alive. No-deal scenario means that instantly, the UK would leave the single market and customs union – these arrangements were initially designed to eliminate impediments such as check and tariffs for EU members. This scenario would also mean the UK abandoning EU legal institutions such as the European Court of Justice and Europol, its law enforcement body. Apart from that, if no deal scenario is to ever come true, the UK would stop contributing to the EU budget, while the previous contributions averaged about 9 billion pounds a year (Lightbown, 2019).

Admittedly, no-deal Brexit is only one scenario and is not taken seriously by some. Yet, even the mere possibility of it happening have already deterred many up and coming companies and startups from basing themselves in the UK. The country’s potential intentions to cut ties with the EU institutions are causing a great deal for disruption and concern even for established businesses with enormous revenues. It is readily imaginable how threatened smaller firms and startups that are looking to secure funding may be feeling.

Some statistics are looking particularly bleak for those deciding to take their business to the UK. For instance, as per the European Investment Fund’s annual report for 2017, only three UK venture funds were backed by the institution as opposed to 20 in 2016 (before Brexit). Some other data shows that the number of UK venture funds in the UK has decreased over the course of the years 2017 and 2018 as compared to 2015 and 2016 (Lightbown, 2019). If this tendency persists, this may as well mean that startups seeking growth capital will not have too many opportunities to choose from.

However, speaking about short-term perspectives, UK startups can enjoy the money available for now. In actuality, while the number of UK investors may be shrinking, other venture funds seems to still be interested in supporting UK-based startups. Thus, one should not limit their opportunities to UK funds and seek money elsewhere. According to recent statistics, even though the overall number of deals staggered in 2018, the amount of capital invested in two post-Brexit years – 2017 and 2018 – surpasses 6.5 billion euro each year. These were the record years with only 2015’s metrics of 5.79 billion euro being comparable (Lightbown, 2019).

These statistics indicate that for now, VCs are willing and able to support UK-based startups. This tendency especially applies to businesses on the verge of scaling globally. A prime example would be Deliveroo that managed to land a whopping $480 million Series F in just two rounds at the end of 2017. Another key factor likely to secure funding flows is VCs wanting to access talent. A scenario in which the UK would experience a massive brain drain is highly unlikely.

After all, the UK’s top ranking education centers will still hold their importance. For example, both the London Business School and the University of Oxford are in the top MBA programs ranked by the amount of VC money raised. Startups emerged with founders graduated from these schools are Adaptimmune Therapeutics, Off Grid Electric and Quipper. Overall, the future of startup funding in the UK is unclear, even though short-term perspectives may still be looking optimistic.

Investment Advice in the UK

Financial Advice Market Sector Trends and Overview

A particularly interesting area of study would be the dynamics of the investment advice sector in the UK. The most relevant data can be obtained from the report “Engaging with UK Financial Advisors: Trends, Concerns, and Opportunities” a comprehensive analysis of the Financial Advice market. The document focuses on major issues affecting IFAs and their businesses. The most recent report draws on the data collected from 2018 IFA Survey and 2018 UK Investor Survey.

The report states that there are a lot of growth opportunities for financial advisors in the UK in the years to come. This tendency can be attributed to the uncertainty that the startup and business scene is confronted with in the face of Brexit negotiations. Both startups and investors are growing apprehensive of starting a collaboration due to the indefinite consequences of the UK’s leave with the no-deal scenario still being on the horizon. Another reason, unrelated to business, is attributed to the country’s aging population that might need financial advice. The report concludes that the UK Financial Advisor remains in strong shape: despite the uncertainty, the number of advisors and advice firms are on the rise, and their average revenues are also growing.

There are some common issues faced by many IFAs when running their businesses. Maybe the most daunting one is the heavy and growing regulatory burden, which is now accounting for the higher exit rate as well as the high level of acquisition activity. The regulations in question are compelling IFAs to question the existing business models. Some of them see switching to restricted status as a way out. Others prefer using independent financial advisor support services or outsourcing investment management. These adjustments are not welcome by many financial advisors: they would not willingly switch to restricted status, and they are hesitant to outsource.

Yet, arguments such as increasing time working with clients and reducing the regulatory burden are encouraging. Besides, full discretionary management outsourcing has lower-cost alternatives. However, advisors may be concerned about the rise of automated investment services.

Key findings from the report include the total number of financial advisor firms at the end of 2017 – 5,281, with as many as 87% being independent (Global Data, 2019). As per report findings, financial advisors contributed 58% of retail investment sales in H1 2018. 28.3% of investors contact financial advisors when they seek to arrange investments. This makes financial advice the second most used channel after direct arrangements with providers (31.4% of UK investor population) (Global Data, 2019). The top threat for two-thirds of investors is the burden of regulatory compliance. The latter is the second most popular reason for leaving the profession after retirement.

Financial Advice Logic

When consulting an investor, a financial advisor might want to look for specific signs of long-term success in a startup. These might include but are not limited to:

- A strong team – according to Ballester (Angel Investment Network), the founding team is the single most important aspect during the early stages of business. As Ballester states, an excellent team demonstrate their passion for the problem that their business seeks to solve. Moreover, they have relevant knowledge, skills and expertise to make it work;

- Clear business culture – apart from the technical aspects, a comprehensive corporate philosophy is what sets a startup apart from its contenders. When seeking to secure funding, it is imperative that the team presents a clear vision regarding doing business;

- A unique, solid business model – many new entrants fail to explain exactly how their idea will generate any revenue in a perspective. Ideally, the suggested model should be original and offer something that no other competitor has managed to offer;

- Good knowledge of market. A business needs to demonstrate a holistic market knowledge because both a savvy investor and a financial advisor will look into the numbers and how market fit the end product is.

While many investors do not have any preferences regarding the sector, the following industries have been gaining particular attention in recent years:

- Health and life sciences;

- Innovation in everyday technologies, including the Internet of Things;

- Fintech;

- Food and beverage;

- Blockchain;

- Media;

- B2B;

- Augmented reality;

- Virtual reality;

- Artificial intelligence, and business applications for it;

- Machine learning;

- Proptech (Global Data, 2019).

Capital Market Theories

Capital Market Theories: Historical Background

Generally speaking, capital market theories explain the relationship between investment returns and risks, namely, predictions of expected gains and losses as well as the effect of investor’s properly diversified portfolios on the mechanisms of the market pricing. Aside from that, capital market theories attempt to provide an understanding as to whether the market is able to ensure that security prices fully and correctly reflect information available. Modern capital market theories take origin in more traditional methods for capital market investment decisions and investment portfolio management that date all the way back to the 1950s.

Back then, when assessing market security and decision viability, individuals tend to rely on rule-of-thumb, the intrinsic value of securities (otherwise known as fundamental analysis) and trends or patterns in security prices (i.e. technical analysis). One of the most typical characteristics of the investment decision-making process before the development of the modern capital market theories is its emphasis on the return of investment. Back then, the role of risk was not properly understood and sometimes not even considered as a significant factor to be heeded.

Fundamental analysis entailed studying the company, industry and economy with the purpose of investing in securities while their market prices were below intrinsic values. When conducted properly, fundamental analysis allowed for selling the said securities later for prices above their intrinsic values. In contrast to the described method, technical analysis did not have impacting individual securities as its main focus. Instead, it dealt with price trends and patterns in order to gain meaningful insights. Certain price trends served as a sign to buy, hold, or sell securities. In turn, patterns were helpful with determining whether capital markets were likely to put an inadequately low or high price on certain securities.

Since the world economics were rapidly changing at the time in light of major political events, traditional capital market theories were no longer able to provide all the answers. It was only logical that since the 1950s, scholars and academics began to question the traditional assumptions concerning the pricing of securities on capital markets. It became clear that there was a need for a new, interdisciplinary approach that would unite existing theoretical frameworks pertaining to capital markets, business finance and investment decision-making as well as test out new hypotheses.

Eventually, scientific inquiries led to a series of new developments including Portfolio Theory (PT), the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), option pricing and the Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT). Interestingly enough, these new developments shied away from concentrating exclusively on return on investment. Instead, they wisely prescribed how to use available information in order to form expectations about the risk and return on securities.

In the 1980s, the focus of investment theory underwent a slight shift once again (Negishi, 2014). That time around, academics were rather interested in the effects of globalisation and increased mobility on capital markets. At the same time, they acknowledged the phenomenon of market uncertainty and near impossibility of making long-term predictions. For this, academics studied efficient market anomalies and imperfection in the pricing of securities.

Role of Capital Market Theory

Portfolio Construction

Portfolio theory (PT) was one of the new developments made by academics back in the 1950s (Negishi, 2014). The modern theoretical framework concerning portfolio construction relies on the work of Markowitz that sought to consider both investment risk and investment return. According to Markowitz, investment in securities was to be assessed based on their impact on the investor’s entire portfolio of investments. Thus, the underlying principle of the modern PT is that given the market uncertainty, investment in a security should not be evaluated strictly on the basis of its relationship between risk and return. Further analysis is needed, and it should be conducted on a larger scale. The end goal is defining the contribution if a security to the overall risk of the portfolio of investments.

The main goal of constructing a portfolio using capital market theories is to maximise the expected return from one’s investments. At that, investors need to decide on the level or risk that they may be willing to accept. Portfolios that carry a balance of the potential of good returns and minimal risks are called efficient portfolios. One of the key concepts to be considered when reviewing the phenomenon of portfolio construction is risk aversion.

It is argued that investors typically display risk mitigating and avoiding behaviors. A prime example would be an investor facing a choice between making two investments whose return would be approximately the same but whose risks vary significantly. In this case, it is only natural to choose the latter option for the sake of risk aversion. This mechanism constitutes the logic behind defining what an optimal portfolio is. Meeting the requirements for an optimal portfolio is somewhat harder than doing so to have one’s portfolio qualified as efficient. Reaching optimality in portfolio construction is striking the right balance between risks and returns.

Choosing the right mix of assets that suit a person’s accepted level of risk, are likely to have the desired return and fit individual circumstances is called asset allocation. Asset allocation is probably the most important decision an investor can make. PT prescribes to avoid risks by diversifying one’s portfolio – a risk management strategy that puts together a wide variety of investments within a portfolio. There is a clear rationale behind this technique: a portfolio made up of different kinds of assets is likely to yield better returns in the long perspective. Diversification is to decrease the likelihood of unsystematic risk events in a portfolio.

Simply put, the positive performance of some investments can mitigate the negative performance of others. One thing to avoid when building an optimal portfolio is perfect correlation – that is, similar response to market influences. It is better if investments respond differently or even in opposing ways. As of now, studies and mathematical modeling have proven that the most efficient number of stocks is 25 to 30 – in this case, they yield the most cost-effective level of risk reduction. Surely, it is possible to add more stocks to one portfolio; however, they are likely to generate benefits at a smaller rate.

To elaborate on the idea of portfolio diversification, it is important to list the key asset classes:

- Stocks (shares or equity in a publicly traded company);

- Bonds (government and corporate fixed-income debt instruments);

- Real estate (buildings, natural resources, livestock, agriculture, water and mineral deposits);

- Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) – a marketable package of securities that follow an index, sector, or commodity;

- Commodities – basic goods required for the production of other products or services;

- Cash and short-term cash-equivalents (CCE) – treasury bills, certificate of deposit (CD), money market vehicles and other investments that are short-term and low-risk investments (Negishi, 2014).

As with any strategy, there are certain advantages and disadvantages to stock portfolio diversification. For sure, a diversified portfolio reduces risk, hedges against market volatility and provides increased returns in the long perspective. However, limited short-term gains may be discouraging to some investors. At the same time, forming a diversified portfolio takes more time than usual as well as incurs additional transaction fees and commissions.

The question arises as to how the portfolio theory may be applied to alleviate investment risks in light of Brexit and political and economic uncertainty. One way to go about making investments in the post-Brexit UK is to use the rule of thumb – diversify one’s portfolio. While this strategy makes general sense at all times, Brexit has its own specifics. One solution to consider is expose one’s portfolio to international funds. Prime examples would be unit and investment trusts or OEICs and ETFs that are authorised in London but with overseas assets. This decision would help an investor hit two goals at once. They will enjoy the world of opportunity that international funds present. At the same time, investors get to retain the protection provided by the United Kingdom statutory regulation of financial services.

Aside from that, any investor who wants to preserve the actual value or purchasing power of their financial resources should entertain some exposure to funds holding assets in more than one currency. For instance, bonds and shares traded in dollars, euros, Swiss francs, and Japanese yen would be up for consideration. Another reason why making a diversified portfolio a priority during Brexit is the rising income that overseas companies and funds may bring. At first sight, UK dividends may seem more than sufficient, bringing shareholders 74% more income as compared to 2010. However, those investors who capitalized on international shares enjoyed advancements twice as high – for instance, 148% for American dividends and 144% for Asian countries.

Efficient Market Hypothesis

The development of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) took place in the 1970s (Negishi, 2014). The modern theoretical framework underlying the concept was based primarily on the work and findings of Fama that later influenced how the capital market was viewed. The most basic assumption of the EMH put forward by Fama stated that the capital market is intrinsically efficient. Thus, the changes in the prices of securities should not be viewed as correlated. Instead, the security prices fully reflect the price implications of all information available in an objective manner. One of the issues that the EMH seeks to explain and tackle is unsound investments made by even the most experienced mutual fund portfolio managers and other professional investors.

Essentially, the EMH suggests that all available information about investment securities (example: stocks) can be obtained from the prices of those securities since it was factored in them from the start. Assuming that this is true, the theory tells us that no matter the amount of analysis, no investor can have a competitive advantage over other investors, collectively known as the market. The EMH does not imply that investors be rational, even though this claim sounds counterintuitive.

Overall, each investor will act randomly; however, when lumped together and constituting the market, they will also be “right.” In this case, it should be noted that be “efficient,” Fama meant “normal,” a rather broad notion. For example, an unusual reaction to an unusual piece of information falls under the category of “normal.”

To gain a better understanding of the EMH, one should outline the three main subtypes. Each of them can provide an investor with some meaningful characteristics about the market:

- Weak-form EMH: all previous information is priced into securities. Therefore, by means of applying fundamental analysis, an investor can obtain enough data on potential returns above market averages. In the short-term perspective, the market does not exhibit any patterns. This means that fundamental analysis will not give an investor any long-term competitive advantages and technical analysis will also be inapplicable.

- Semi-strong form EMH favors neither fundamental nor technical analysis. WIthin this framework, both types are unable to provide any competitive advantage for an investor. New information is immediately priced into securities as opposed to the idea of only storing previous information.

- Strong-form EMH implies that all information, both public and private, is factored into stocks, and no investor can gain advantage over the entire market. However, the strong-form EMH does not state that not a single investor is capable of gaining exceptionally high returns in an investment. The averages described by the strong-form EMH naturally imply that there are outliers: both those who can gain a lot as well as those who fail miserably on the market. Therefore, the majority of investors are closer to the median – they are normal. Moreover, winning or losing massively may often be attributed to the matter of luck.

There is still enough controversy around the overall concept of the efficient market hypothesis. Proponents of the EMH, even in its weak form, tend to prefer investing in index funds or certain exchange-traded funds. The reason behind it is their passive management: the goal of these funds is merely to match, not outperform, market returns. Instead of trying to beat their competitors, EMH investors buy an index fund that makes investments in the same securities as the average benchmark index. On the other hand, some investors oppose the idea of certain determinism of the EMH. Among the most vocal opponents are technical traders that prefer to look at short-term trends and patterns and locate buying and selling opportunities based on their observations.

One example of how EMH can be applied when making decisions in the post-Brexit UK is to follow ongoing political events closely. It is said that even when the future of the UK and the EU was still uncertain, i.e. before the referendum, the effects of the looming decision were already observed in financial markets. Politics and economics are tied together as expected: after all, market rates are mean estimates. First and foremost, probabilistic weighted averages of the world of outcomes are being constantly factored in. The past cannot provide enough guidance for the future. Moreover, the country’s economics do not allow controlled experiments to predict outcomes.

Thus, the case of Brexit requires good knowledge of the political scene and even intuition to make the right decisions. In summation, in the framework of the described theory, the current situation can be described as semi-strong EMH. Investors can still use their analysis of short-term trends to gain advantage or at least, to avoid failure.

Capital Asset Pricing Model

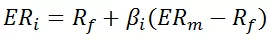

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) draws on the modern Portfolio Theory (PT). CAPM explains the relationship between systematic risk and expected return for assets, stocks in particular. This model is routinely used in finances in order to price risky securities as well as generate expected returns for assets based on the risk of those assets and cost of capital.

- ER1=Expected return of investment;

- Rf = Risk-free rate;

- βi = Beta of the investment;

- ERm = Expected return of market;

- (ERm – Rf) = Market risk premium.

Basically, investors expect a compensation for risk and the time value of money invested. In the CAPM formula (see Figure 6), the risk-free rate means the time value of money. The rest of the components of the formula stand for additional risks associated with an investment. The beta of a potential investment is a special measure that defines the amount of risk that will be added to a portfolio. At that, if a stock displays more risks that the average of the market, the beta will be greater than one. Logically, if a stock has a beta less than one, the formula will imply that adding a particular asset will reduce the risk of an entire portfolio.

Further, a stock’s beta is multiplied by the market risk premium, which stands for the return expected from the market that is above the risk-free rate. Finally, the last step in computations is adding the risk-free rate to the product of the stock’s beta and the market risk premium. As a result, an investor can now learn the required return or discount rate that can later be used to determine the value of an asset. The end goal of using the CAPM formula is to make sound judgment as to whether a particular stock is fairly valued given the comparison of its risk and the time value to its expected return.

The main advantage of the CAPM is its simplicity when it comes to calculations and conceptualisations. Besides, by using the CAPM formula, investors can easily compare and contrast investment alternatives. However, the theory should be critically evaluated since some of its key assumptions seem not to hold in reality. For instance, the use of beta in the formula raises reasonable doubts. The variable is tied to a stock’s price volatility, and yet, price movements in both directions cannot be considered as equally risky. The look-back period for understanding a stock’s volatility is also far from being a standard since stock returns do not comply with normal distribution.

Further, the CAPM cannot be used over an extended period of time. Originally, the formula assumes that the risk-free constant will remain the same during the discount period. However, in reality, an increase in the risk-free rate also increases the cost of the capital used in the investment. As a result, the stock can give a wrong impression of being overvalued. Third, the market risk premium is only a theoretical value and cannot be seen as an asset to be purchased or invested. Lastly, the most serious critique of the CAMP is its implication that future cash flows can be evaluated for the discounting process. The opponents of the CAMP argue that if suppose, an investor could make very precise predictions regarding the future return of a stock, the CAPM would not even be necessary.

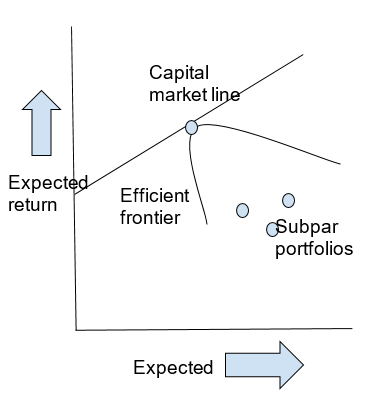

The main use of the CAPM is risk management of stock portfolios. Theoretically, a perfectly optimised portfolio would exist on a curve called the efficient frontier as seen in Image 2. The graph shows that the more returns an investor wishes to gain (y-axis), the more risk he or she will have to accept (x-axis). Merging the CAPM with the Modern Portfolio Theory, it is safe to assume that the potential return of a portfolio increases in a certain proportion to increasing risks. This relationship can be seen reflected in the capital market line that starts on the y-axis with the risk-free rate. It is assumed that the best portfolio needs to be right on the line while all the portfolios to the right of the line lack efficiency.

The problem with the described model is that the capital market line and the efficient frontier are quite difficult to define. Yet, a valuable lesson that this model can teach an investor is that there always exists a certain trade-off between increased return and increased risk. Building a portfolio that perfectly fits on the capital market line can be doable only in theory. Therefore, it is much more common for investors to take on more risks as they chase additional return.

Given the many arguments against the use of the CAPM, it may be difficult to see its practicality in portfolio construction. Yet, what definitely has value is using the CAPM as evaluation tool of the feasibility of future expectations or drawing comparisons. Apart from that, an investor can also use the described concepts to compare their portfolio or individual stock performance to the market’s average. These observations can help an investor to question how his or her portfolio was constructed in the first place and why it is to the right of the capital market line.

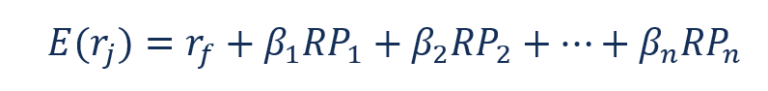

Arbitrage Pricing Model

The Arbitrage Pricing Model (APT) is a logical successor of the CAPM; the two models are often compared to each other. The theory behind the APT was developed in 1976 by the economist, Stephen Ross. In a nutshell, the APT states that it is possible to forecast an asset’s returns using a linear relationship that considers various macroeconomic factors. What this pricing theory has to offer analysts and investors is a comprehensive multi-factor model for securities. Akin to the CAPM, APT seeks to explain the relationship between expected risks and returns. However, the APT takes up a more complex approach, in which it seeks to cover as many contributing factors as possible.

One of the key assumptions that the APT makes is that one should not always rely on the market price of a security for fairness. Instead, one should accept that market action is often far from efficient. The result of this imperfection is assets being mispriced – either overvalued or undervalued, which happens for a brief period of time. However, soon enough, market action interferes and corrects the situation: the price returns to its fair market value and becomes balanced again.

Proponents of the APT see temporarily mispriced opportunities not as aberrations but as opportunities to make profit while taking minimal risks. The flexibility and complexity of the APT model gives investors and analysts an opportunity to customise their research. On the downside, however, the application of the APT is quite challenging and time-consuming as it requires determining all the various contributing risk factors.

One of the key suggestions of the APT is that investors are likely to have to diversify their portfolio – a process described in detail earlier. At the same time, however, every investor is to settle on their own unique profile of risk and returns on the premise of the premiums and impact of the macroeconomic risk factors. Those investors that decide to take advantage of the differences in expected and real return usually do so by using arbitrage.

Just like the CAPM, the APT assumes that the returns on assets comply with a certain linear pattern. An investor can mitigate deviations in returns from the linear relationship by employing the so-called arbitrage strategy. In general, arbitrage is a common practice entailing a simultaneous purchase and sale of an asset. By doing that, an investor makes a profit by taking advantage of slight pricing discrepancies.

The APT, however, has its on take on the definition of arbitrage. Within the described theoretical framework, arbitrage is not considered a completely risk-free operation, even though a high probability of success is implied. The APT is useful for determining the fair market value of an asset in theory. Once the value is determined, it is possible to set out on a search for slight deviations from the fair market price and trade in accordance with that.

- E(rj) – Expected return on an asset;

- rf – Risk-free rate of return;

- ßn – The level of volatility of an asset’s price with respect to factor n, which is a macroeconomic variable causing systemic risk; how sensitive the asset is to factor n;

- RPn – Risk premium of factor n.

The question arises as to what factors are usually heeded when applying mathematical modelling. There is a great flexibility regarding the choice of appropriate factors. In fact, investors and analysts are free to choose any number and any type. As of now, there is no general consensus on what factors should be used to make the best predictions. Therefore, it is easy to imagine how to investors could draw vastly different conclusions when analyzing the same security. Yet, some researchers, such as Ross, argue that some factors should be given a high priority due to their potential to help to predict price. These factors include shifts in inflation, gross national product and the yield curve.

Option Pricing

The last and probably the most sophisticated theory covered in this chapter is the option pricing theory (OPT). In a nutshell, the OPT employs a set of variables such as exercise price, stock price, volatility, interest rate and time to expiration to evaluate an option in theory. Basically, the OPT can help with a rather precise estimation of an option’s fair value that can later be used by traders wishing to maximise their profits. The OPT is a blanket term covering a range of different mathematical models that include Black-Scholes, binomial option pricing and Monte-Carlo simulation. All these models are characterised by rather great margins for error since they derive their values from other assets.

The main objective of the OPT is to compute how probable the execution of an option, or it being in-the-money (ITM) is, at expiration. The commonly used variables for calculations are underlying asset price (stock price), exercise price, volatility, interest rate and time to expiration. The latter is defined as the number of days between the calculation date and the option’s exercise date. The typical logic behind the process is that the longer an investor is to exercise the option, the greater the probability that it will be ITM at expiration. In the same line, the volatility of an underlying asset is associated with a faster expiration before being ITM.

Typically, there is an association between increased interest rates and increased option prices. Academics distinguish between marketable and non-marketable options since they require different valuation methods. Real traded options are difficult to evaluate as open market metrics should be considered. Yet, knowing the value at least in theory gives traders an opportunity to make conclusions regarding the likelihood of profiting.

The first major development in the field of option pricing was made in 1973 by Fischer Black and Myron Scholes. The formula put forward by those two researchers is employed to calculate a theoretical price for financial instruments with a known expiration date. The original model manipulated five input variables:

- Strike price of an option;

- Current price of the stock;

- Time to expiration;

- Risk-free rate;

- Volatility. Since volatility cannot be directly observed, Black and Scholes suggested academics and investors use approximation.

Currently, some academics consider dividends to be a meaning sixth input to be used in calculations.

One of the key assumptions made by the Black-Scholes model is that stock prices follow a log normal distribution since asset prices cannot be negative values. Among other assumptions is complete disregard for transaction costs or taxes. Apart from that, it is implied that the risk-free interest rate constitutes a constant for all maturities. The Black-Scholes model allows for short selling of securities with use of their proceeds. Lastly, according to the authors, it is impossible to take advantage of an arbitrage opportunity without taking certain risks.

Clearly, some of these assumptions only work in theory and do not stand real-life testing. For instance, it would be unreasonable to assume that volatility remains constant during the entire lifespan of an option. Normally, this is not the case because the ever changing level of supply and demand moderate volatility. Besides, the Black-Scholes Model seems to only be working for the European Style options – ones that are executable only once they reach maturity. The theory ignores the execution of American Style options that is not exactly tied to their maturity. They can be exercised at any moment before and including the day of expiration. However, the Black-Scholes model gained much critical appraisal for its straightforwardness and practicality. It is still highly regarded by both investors and academics.

Brexit and Stock Prices

Shahzad, Rubbaniy, Lensvelt, and Bhatti (2019) examined the reaction of the UK stock market to a number of events (N=27) associated with the probability of Brexit. Their findings showed that overall, the market reacted negatively to the events showing a high likelihood of hard Brexit. However, further dissection of the analyzed events into two categories – pre- and post-referendum – helped to differentiate the market reaction.

Namely, pre-referendum events, not tied to the exact date of announcement, presented great uncertainty. Thus, markets reacted accordingly, which was expected. However, post-referendum events that allowed markets to get a better understanding of the shape that the UK-EU economic relations were taking brought optimism back. According to Shahzad et al. (2019) more positive reactions were observed in those investors that traded internationally and dealt with foreign stock. They displayed more certainty in their decisions due to their portfolios being exposed to foreign markets.

In light of these findings, it is possible to discuss how the aforementioned pricing models could relate to post-Brexit investments. First, it appears that volatility as one of the key parameters in Black-Sholes models would be difficult to approximate. It is true that this parameter has never been a constant, but predicting its value is as challenging as ever. CAPM may prove to be inefficient due to the impossibility to determine the efficient market line due to how volatile the markets are. Arbitrage pricing, however, may come in handy for some investors. Due to the plummeting sterling, many industries decrease prices as part of their anti-crisis strategies. Perhaps, some investors may benefit from the price difference in case the prices will go up again once the situation has stabilized.

Conclusion

Despite the volatile political climate, the UK remains one of the world’s strongest economies. As one of the most trustworthy business ranking, Doing Business, has shown, pre-referendum and post-referendum market conditions do not vary much. The UK shows significant improvement in some criteria such as trading across borders but displays shortcomings in other areas, for instance, protecting minority investors. Perhaps, the main reason why the UK stay afloat among the chaos of Brexit negotiations is its strong financial politics prior to its decision to leave the EU. Over the course of the last ten years, the government has made a meaningful effort to relieve regulations and make the country a comfortable place to start a business.

Brexit is likely to take its toll on the UK business environment and affect two aspects in particular – the startup scene and stock investment. Some startups are likely to be scared off by the possibility of hard Brexit that makes the future of international regulations uncertain at best and gloomy at worst. The second issue to be tackled is the volatility of investment markets that will require an even more thoughtful application of the modern capital market theories, namely portfolio diversification and arbitrage pricing.

References

Clarke, P., “US Investment Banks Dominate in the UK as Revenues Slide,”

Finder, “Investment Statistics,”

Global Data, “Engaging with UK Financial Advisors: Trends, Concerns, and Opportunities,”

HM Government, “The Coalition: Our Programme for Government”.

House of Commons Library, “Brexit and Financial Services.” Web.

House of Commons Library, “Business Statistics.” Web.

House of Commons Library, “Financial Services: Contribution to the UK Economy.” Web.

Lightbown, S. “How Brexit Could Affect Startup Funding in the UK.”

McIntyre, A., “10 Major Trends Driving Banking In 2019: Banking’s Evolution Accelerates.”

Negishi, T., “History of Economic Theory,” Elsevier, 2014.

OECD, “United Kingdom,” Web.

Shahzad, K., Rubbaniy, G., Lensvelt, M.A.P.E. and Bhatti, T., “UK’s Stock Market Reaction to Brexit Process: A Tale of Two Halves,” Economic Modelling, Volume 80, 2019, pp. 275-283.

World Bank Group, “Doing Business 2016.” Web.

World Bank Group, “Doing Business 2019.” Web.

World Bank Group, “Doing Business 2019. Economy Profile United Kingdom,”