Introduction

In the given paper, the issues concerning the way students and teachers in Saudi Arabia access, use and treat the CALL standard in EFL instructions concerning the preparatory year program at the University of Tabuk are going to be considered and the existing approaches are going to be evaluated. Since the world is merging into a single entity and the relationships between various countries are becoming increasingly enhanced, it is necessary to consider the idea of using computer technologies as one of the fastest and the most efficient ways to establish relationships with the other countries and introduce the ESL standards into the Tabul English course curriculum. However, it must be admitted that due to the innovative nature of the CALL procedure, certain complexities concerning the implementation of the given ideas arise. Hence, the necessity to consider the existing CALL and assess its positive aspects and drawbacks, as well as find the root of the problem and offer possible solutions emerges. It is necessary to add that the given paper will contribute to the improvement of the CALL technologies and the development of the existing CALL programs.

Since the study we plan to do is essentially a survey of the available access to, actual use of, and attitudes to computers in EFL teaching, in a particular context (refer to section of ch1 where you told us this), we will review the following areas:

- the Students’ Attitudes towards the Use of CALL Programs;

- The Teachers’ Attitude towards the USE of CALL Programs;

- The Comparison of Teachers’ an Students’ Attitude towards CALL;

- The Problems of Accessing CALL Programs in the Arab World;

- The Existing Computer Applications for ESL Learners;

- The Teaching Approaches in CALL for ESL Students

- Concept of Attitude,

- Attitude and Language Learning,

- Attitude toward Computers in Instruction,

- Diffusion of Innovation Theory,

- Applications of CALL,

- Studies on Student’s Attitudes Towards CALL,

- Studies about students attitudes towards computers in Arab world,

- Studies on Attitudes of Teacher,

- Teachers attitudes towards computer in Arab world,

- Computer Attitude Scales,

- Variables Related to Teachers’ and Student’s Attitudes in Using Computer.

An integrated summary of all the theories and concepts that will be utilized in the study will conclude the chapter.

Concept of Attitude

This study shows that attitude is very essential for the achievement of the goals and success of an individual with regards to their future endeavors and career. With such importance, it can also be derived that studying attitude in its entirety is best to gain insights on the complexity of its idea and how could it help one’s goal to be achieved.

Eagly & Chaiken (1993) purported that the concept of attitude was the central theme when social psychology emerged and they argued that it is important that in any concept to be discussed it should be started where it begins. It is essential to add that in the given case, social psychology is not the object of the research, but rather the tool that allows to approach the issue in a more efficient way and consider it closer, since the research in social psychology permit to narrow the scope of the research since AL has learned from attitude research in social psychology. Thus, taking this argument into perspective the concept of attitude must be discussed in the light of Social Psychology.

Thurstone (1946), a pioneer of attitude research, offered a useful definition of attitude as follows: “the intensity of positive or negative effect for or against a psychological object. A psychological object is any symbol, person, phrase, slogan, or idea toward which people can differ as regards positive or negative affect” (p. 39). Hence, it is obvious that by analyzing people’s attitudes towards the idea of using computer technologies in language studying, one will be able to come to a certain conclusion concerning the efficiency of using computer technologies in ESL teaching and the issues that arise in the course of the CALL application. It is important to mark that Murphy, Murphy, and Newcomb (1937) define attitude in the following way: “Attitude is primarily a way of being ‘set’ toward or against certain things” (p. 101). In another context, English and English (1958) defines attitude as “an enduring, learned predisposition to behave in a consistent way toward a given class or objects; a persistent mental state of readiness to react to a class of objects as they are conceived to be” (p. 42).

Mantel-Bromely (1995) further suggests that attitude has both emotional and evaluative nature as it indicates the level of one’s liking or disliking a certain object. Such a contention was affirmed also by other researchers such as Rajeski, (1990) and Zimbardo and Leippe(1991) who believe that attitude is comprised of three components and these are: affect (the degree of liking of the object the person has); cognition (that means the person’s knowledge about the attitudinal object); and behavior (reactions and intentions regarding the object).

Two basic definitions of attitude that will form the basis of this research are from Palaigeorgiou, Siozos, Konstantakis, Tsoukalas (2005) and Smith, Caputi, and Rawstorne (2000). The former is a general one, encapsulating the earlier ones mentioned above: “attitude” is “a positive or negative sentiment or mental state, that is learned and organized through experience and that exercises a discrete influence on the affective and conative responses of an individual toward some other individual, object or event” (p.39). The second is specific to our object of interest: it defines “attitudes toward computers” as “a person’s general evaluation or feeling of favorableness or unfavorableness toward computer technologies (i.e. attitude toward objects) and specific computer-related activities (i.e. attitudes toward a behavior)” (p. 61). The choice of these particular definitions has been determined by the fact that they offer a versatile presentation of the concepts they denote, the definitions are up-to-date, and the wordings are applicable to the context of the proposed study.

Attitude and Language Learning and Teaching

It is during the twentieth century that the study of attitude came into prominence (Smith, 1971). Smith (1971) commented that something had been overlooked in the past which is an important factor that is only now beginning to be investigated – and that is attitudes. Attitude is considered one of the affective variables that have a great role in second or foreign language acquisition (Ganschow et al., 1994).

Much has been researched about the role of attitude, in conjunction with motivation, as an individual difference of learners which may influence their language learning success (refer to Gardner, etc) maybe say a bit more but not a lot about that. However, in our study, the focus is on the role of attitude, of teachers as well as learners, in syllabus development/evaluation of a new method of teaching/learning (i.e. computers…) refer to materials evaluation/syllabus development literature. In classic research on motivation (Dornyei…) one reason for students being motivated, that emerges strongly is what has been termed ‘intrinsic motivation’. This is the motivation that arises from students having positive attitudes to the teaching methods and materials and so forth used in their course. Clearly, if students (and teachers) have positive attitudes to the involvement of computers in ELT, even if not much has yet been implemented, this suggests a great potential for students to be intrinsically motivated if more computer use was deployed. Hence the exploration of attitudes to computers in ELT is an important area to investigate while computers are being innovated into so many teaching situations. Elaborate on the use of attitude in syllabus/curriculum development studies and in program and materials evaluation.

The great importance of attitudes in language learning and acquisition has been emphasized by a number of other researchers (Ellis, 1985; Gardner & Lambert, 1972; Merisuo-Storm, 2006; Savigon, 1976). Savigon (1976), for instance, treated attitude as the most valuable factor in second language learning. Attitude plays an important role in the formation of motivation toward language learning itself; this means that attitude has an important connection with other affective factors (Gardner & Lambert, 1972). The same researchers, Gardner & Lambert (1972:134), mentioned that “the learner’s motivation for language study, it follows, would be determined by his attitudes and readiness to identify and by his orientation to the whole process of learning a foreign language” (p. 134). The same idea was supported by Merisuo-Storm (2006), who established a direct connection between motivation in language learning and stable attitudes in the mind of a learner.

Masgoret and Garden (2003) in their meta-analysis study explored and confirmed the significant relationship between second language achievement to five attitudinal or motivational variables adapted from Gardener’s previous model on social education in comparison with the factors of availability of language in community and the age of learners to check if they have any moderating effect. The five variables under study were: integrativeness, attitudes towards the learning situations, motivation, integrative orientation, and instrumental integration. The study was based on 75 independent samples comprising 10,489 individuals. Fifty-six samples came from published sources while 19 were from unpublished articles and dissertations. The study results based on three hypotheses categorized three relationships under study: first, it showed that the 5 variables under study were found to be positively related to achievement in a second language learning. Second, it has been observed that motivation has a higher correlation in relation to second language achievement in contrast with the other variables. Finally, the results indicated that neither the availability of language in the immediate environment nor the age of the learners moderated language learning.

The role of affective factors such as attitude and motivation in language learning turned out to be a possible answer to the following paradox: how it is possible for some people to learn a second language perfectly and proficiently while other learners, though the same opportunities and setting to study language are available for them, fail their studies since all other answers attributed to teaching methods, knack, or pedagogical matters have failed (Gardner & Lambert, 1972).

Relevant to our concerns, Mantle-Bromley (1995) stated that “attitudes influence the efforts that students expend to learn another language, then language teachers need a clear understanding of attitudes and attitude-change theory in order to address these issues in the classroom” (p. 373). The change theory can be illustrated by its main hypothesis that says that the behavior of potential recipients is constrained or controlled by their attitudes towards the various aspects of a certain objects (Steinberg, 2000). Thus, the investigation of students’ attitudes would help educators figure out the learners, improve their teaching methods, probably, bringing positive changes and modifications to the course syllabus on the whole. This is precisely our goal in exploring student and teacher attitudes to computer use in ELT in our university.

In addition, it is necessary to discuss the Monitor Theory of Krashen as it is a valuable theory for second language acquisition that emphasizes motivation that is created by positive attitudes of a learner towards the knowledge and its acquisition which is relevant to the proposed study. The theory presents particular interest since it is greatly appreciated and criticized a lot at the same time. For instance, Omaggio-Hadley (1993) questions the propriety of the authors’ strict distinction between learning and acquisition and proves that the monitor fails to work as prescribed. The theory suggests that the affective filter in language acquisition has had a large impact on the role that affective factors play in language acquisition (Bacon & Finnemann, 1990). The hypothesis of Affective Filter by Krashen (1987) deserves some more attention as it is related to students’ attitudes in the form of variables that largely affect the situation along with the successful acquisition of language.

Krashen (1987) further stated in his study that the Affective Filter hypothesis reflects the link between the different affective variables and the course through which a second language is acquired by putting forth that learners vary based on the strength and effectiveness of their affective filters. Learners that do not have a positive outlook towards learning a second language will not only be weak at grasping existing instructions but will also be less likely to ask for input; however, they will also have a considerably strong affective filter. What this means is that such individuals, even if they comprehend the instruction, will not be able to process it to the parts of their brain that retain language acquisition. It was deemed from the study that those learners who have a more positive outlook towards the second language would not only learn faster but would also get more input and hence have a considerably weak filter which basically makes them more open to learning so that they will be able to get “deeper”( p. 31). Thus, it shows the value of the studied theory is in its establishment of the connection between effective factors and language acquisition.

Hence, the importance of the research conducted in the sphere of ESL teaching is one of the most crucial issues to consider. Once improving the teaching strategies and allowing students to use the modern technologies to acquire the necessary skills, one is likely to succeed in teaching English. Eliminating the existing problems is, therefore, the most important task for ESL teachers.

Attitude toward Computers in Instruction

Following the definition of Smith et al., (2000) (see the end of 2.1), attitudes could be applied not only to all aspects of computer technologies like attitude towards computer programs, training, and games but also to computer-related activities, such as taking certain computer tests to check the students’ progress, helping the students plunge into the atmosphere of the English culture, providing them with certain audio or visual activities aimed at mastering English communicational skills, etc. In fact, Mitra and Hullett (1997) found in their study that attitudes toward computers consist of many elements like attitudes toward computers in instruction, technical support for use of the computer, and attitude toward access to computers. Palaigeorgiou et al. (2005) illustrated that computer attitude evaluation usually involves statements that assess the persons’ interactions with computer hardware, software, other people relating to computers, and activities that include computer use. In the given study, the issues concerning people’s attitudes towards the new methods of teaching ESL students are going to be considered and commented on; in addition, probable solutions for the emerging problems are going to be offered.

The use of computers in instruction has opened the door for research to discuss all aspects of computer use in teaching. Students are one of the main sources that researchers have addressed to get more understanding of integrating the use of technology in classrooms. Students’ attitudes toward using technology in classrooms are crucial to the success of the implementation of technology. Al-Khaldi and Al-Jabri (1998) stated that students’ attitudes toward computers are significant determinants that might affect the success of computer implementations. The success of any integration of the use of computers in instruction depends greatly on learners’ and teachers’ attitudes toward them (Selwyn, 1999, cited in Palaigeorgiou et al., 2002). It is also essential to add that in the given paper, the actual studies of various manifestations of people’s attitudes towards the issues of CALL are going to be reviewed. Hence, the paradigm of the way people react to the novelties in the given sphere can be traced, which will lead to realizing the true concept of CALL that modern teachers and students have. Therefore, it becomes possible to provide the necessary changes to the existing CALL methods, adjusting them to the needs of the students and making the existing CALL means of teaching most efficient and providing the most fruitful results. Creating the auspicious atmosphere for studying the language, teachers will be able to help students absorb the knowledge better and faster, thus, contributing to the development of the student’s academic life and enriching their academic experience.

CALL Use and its Diffusion

Change is inevitable and this extends to language learning and teaching methods as much as anything else. Since the 1980s, there has been tremendous interest in the role of new technologies in the improvement of English teaching and learning processes. This has led to the development of many CALL applications such as we reviewed in (section… currently 2.5). One aim of our study is to explore reported access to and use of CALL in our context at the present time. As described in (refer to the section of ch1), this might help guide those in whose hands future teaching and learning development lie. In this connection it is useful, then, to review the way in which innovations spread.

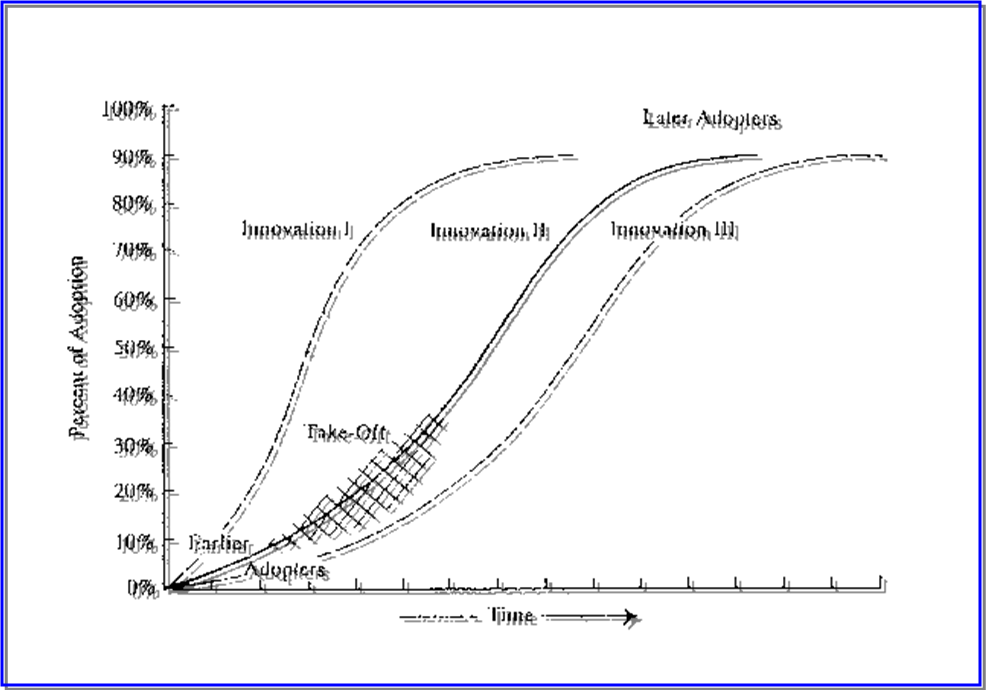

Everett Rogers (1983) proposes a theory of the diffusion of innovation that can form a framework for understanding the rate of adoption of computers, the Internet, and CALL. According to Rogers and Scott (1997) diffusion is the course through which an innovation is dispersed through some defined channels over a period of time to different members of a particular social structure (see Figure 1). Rogers’ theory proposes that the classical S-curve is a good model of the cumulative rate of penetration of innovation (such as CALL) throughout a population (such as teachers and learners of EFL, in the world, or more specifically in KSA). Rogers was especially emphatic about the fact that innovation spreads at different rates: ”A slow advance, at the beginning, followed by rapid and uniformly accelerated progress, followed again by the progress that continues to slacken until it finally stops: These are the three ages of…invention…if taken as a guide by the statistician and by the sociologists, (they) would save many illusions”. (Tarde, 1962, p.127) In Figure 1 the three innovations might be different teaching methods, such as communicative or task-based, or they might be different technologies, such as audio tape recorders, overhead projectors and computers. Or they might represent different specific CALL applications.

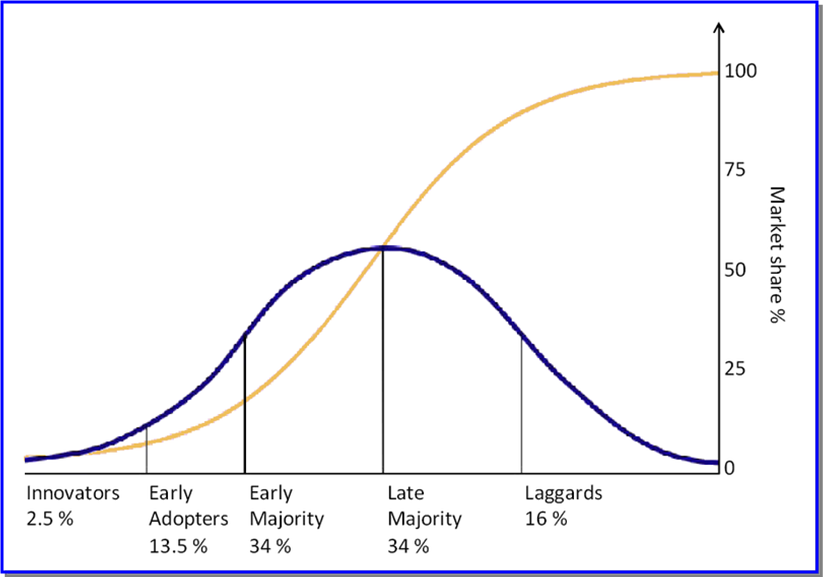

Figure 2 clarifies the theory that a tiny number of innovators are first to adopt the new idea, followed by early adopters. As the “early majority” climbs on the bandwagon, two things occur. First, the median point of the community or population is reached. Second, the new idea diffuses to the “late majority” and “laggard” segments of the population at about the same rate it spread to the innovators, early adopters, and early majority. The result is the classical bell curve (see Figure 2). Add here something about what point on the curve you think CALL is at in the world? In KSA in general? and In your university? (The last you promise to further illuminate from your study).

Although thinking more about economic and technological innovation than pedagogical change, Dodgson and Bessant (1996) brought up the key issue of ‘absorptive capacity’ and defined seven stages of diffusion. The authors proposed that making resources available or distributing the new technology far and wide counts for nothing if the prospective beneficiaries do not possess the capability to put the resource to good use. This would be especially true of CALL too. As to the stages of innovation diffusion, their analysis was as follows:

- The opportunity or need must exist and be recognized;

- The change proceeds with a search for alternatives;

- Comparison of available innovations, ideas and practices take place;

- Opting for the most promising alternative

- Acquisition or purchase;

- Putting the innovation to use;

- Re-learning and adapting after initial use.

Rogers conceded that early innovation is very often associated with the right attitude, as well as the intellectual and financial advantages, though there is nothing inevitable about the adoption of innovation. Hence in our study, we research attitudes of teachers and learners, as well as their current access to and use of the innovation.

Viewing sociology as he did – a dynamic mass of minute interpersonal transactions – Tarde realized the primacy of imitation and innovation (Place-Based Education Evaluation Collaborative, 2003). Other contributions by Tarde that resurfaced in the Chicago School were the “group mind” (underlying herd or crowd psychology) and economic psychology.

Diffusion theory essentially addresses the communication problem: how rapidly do new ideas enter the mainstream, as it were, and gain universal acceptance? As originally conceived, the theory glossed over the practical usefulness of a new idea or the balance of costs and benefits. Mass marketers and advertisers saw the potential, however, of being able to displace innovation curves to the left, i.e. induce a faster rate of acceptance in a community or national market. For us, understanding better, through our study, the current availability and use of CALL in our context might lead to us also being able to make proposals that would displace to the left the innovation curve in our institution, i.e. accelerate the adoption of useful CALL applications especially in relation to ELT.

As per the diffusion theory, there are over five varying stages during which the process of adopting any type of innovation occurs. To start the very first stage is of knowledge where one receives the idea of the existence of an innovation, ergo becoming aware of its existence. During the first stage, an individual will simply be aware of, but not have any real knowledge on the subject. The second stage is the stage of persuasion, where the individual then becomes highly interested in gaining knowledge on the innovation. The third stage involves decision-making for the individual as he/she looks at the pros and cons of the innovation in order to come to a conclusion on whether he/she should go forth towards acquiring it or not. The fourth stage has a more practical approach as it involves implementing the decision made in the third stage. The fifth and final stage involves confirmation.

There is a myriad of factors that help in determining the probability of an individual or a group of people actually adopting an innovation, along with the time frame within which they may adopt it. In general, terms, if a new innovation is of higher quality and utility than the corresponding one to precede it, the likelihood is that it will be adopted in eventuality. On the other hand, if the innovation is not aligned with the moral values of its target audience then it is most likely going to go ignored.

In the context of internet and computer innovation in Saudi Arabia, it was deemed by Sait, Al-Taweel, and Hussain (2003) that there has been already a considerable influence of the Internet and computer on Saudi social, economic, and education systems. Specifically, Saudi education systems are the first that had adopted and accepted innovation in the internet and computer since they had realized its importance in educating their students and broadening to knowledge. Early investigations of Internet adoption and diffusion in Saudi academia demonstrated that professors are in the early stages of adoption (Ghandour, 1999). More recent studies have reported similar trends (Al-Asmari, 2005). This only shows that there is now a huge and extensive growth coupled with slow adoption of innovation in the internet and computer in different sectors of the industry.

Types of CALL Application

Computers in learning can be used in different ways. Taylor (1980) and Levy (2006) both propose that computers in learning are used in three different methods: computer as a tutor, computer as a tool, and computer as a tutee. Computers as a tutor mean that students get tutoring from the computer, which attempts to play the role of teacher. For example, the computer provides material, gets the students’ responses, assesses those responses, then decides what to present next based on the learners’ responses (Taylor, 1980). Using computers as a tool means that students seek help from computers in different subjects by accessing the internet, or use computers as word processors, or the teacher uses it to present Powerpoint slides. Using computers as tutee refers to the process in which the student or the teacher gives the computer some information or talks in a language that the computer understands and the computer in some way responds. All these have been implemented for English teaching and we may expect to find some of them in use in our context.

Slightly differently, Warschauer (1996) divides CALL typology and applications in language learning into three different types: computer as tutor; computer as stimulus; and computer as a tool. Using computers as a tutor again means that the computer teaches things such as grammar, listening, reading, vocabulary, text reconstruction, writing, and comprehension. Using the computer as a stimulus means that the computer is used to help learners generate discussions, or synthesize critical thinking. Communication in support of collaborative writing, the internet, grammar checkers, word processing, concordance, reference, and authoring programs are again typical uses of computers as a tool (Warschauer, 1996).

Currently, CALL takes many forms that meet different learner needs in relation to many different language skills, whether via CDs or the internet on a computer, or most recently on mobile phones.

Warschauer and Healey (1998) illustrate different applications of CALL. Speaking applications incorporate voice recording and playback to allow learners to compare what they said with the model. Another application is the drill application which contains games that use the power of computers and competition for collaboration to motivate language learning. Writing applications involve programs that help learners in the pre-writing stage to create and outline their ideas.

Other writing applications are word processing, spell checkers, and dictionaries. Sokolik (2001) states that computers offer language learners six applications: drills, adaptive, testing, corpora and concordance, computer-mediated communication, and multimedia production.

Literature applications mean giving learners different literature from different disciplines (Beatty, 2003). According to Beatty (2003), literature “has a high degree of fidelity, or authenticity, in that the learning materials are both extensive and taken from real-world source” (p. 57). Collie and Slater (1987) look at the use of literature in language teaching as authentic material, language enrichment, and personal involvement. Literature applications offer learners exposure to different styles, genres, contexts, terms, vocabulary, and acronyms in different fields in the language they learn.

Another application of CALL is corpus linguistics which refers to the study of a body of texts (Beatty, 2003). It “involves the examination of linguistic phenomena through large collections of machine-readable texts” (Cheng et al., 2003, p. 174). The main goal of corpus linguistics is to figure out the models of authentic language use through actual usage analysis (Krieger, 2003).

Another application is computer-mediated communication (CMC). CMC is seen today as one of the computer applications that have the greatest impact on the field of language learning (Warschauer, 1996). Warschauer (2004) points out that extensive interaction is seen as a tool to help language learners enter new societies and communities and familiarize themselves with new discourses and genres. He believes that it is no longer sufficient for learners to communicate with others merely to practice what they learned in language classrooms. Peterson (1997) mentions that one of the main advantages of CMC is promoting autonomy in learning by providing an environment for learning that is less restrictive than the one in the conventional classroom. It enables language learners to communicate inexpensively with native speakers of the target language as well as with other language learners 24 hours a day and from different places like classrooms, home, or work (Warschauer, 1996). CMC also makes learners from different levels, backgrounds, types, and learning styles equal. Warschauer et al. (1996) state that CMC applications provide more equal participation to learners who are often discriminated against or excluded, including minorities, shy students, women, and learners with strange learning styles.

There are two kinds of CMC, Synchronous and Asynchronous; Synchronous CMC means that the interaction is taking place in real-time. An example of that is when learners sit in front of the computer, read, respond, and discuss topics with each other via a chat or messenger facility or Skype (Chapelle, 2003). This type of CMC could also take place over a mobile phone through text messaging, voice messaging, or both (Chapelle, 2003). Smith et al. (2003) mentioned that the internet is the representative of synchronous communication “Internet Relay Chat (IRC) exemplifies synchronous communication” (p. 705).

The second kind of CMC is Asynchronous communication which is the opposite of synchronous and means that interactions do not take place in real-time. Examples of Asynchronous communication are bulletin boards (Chapelle, 2003) and e-mail (Smith et al., 2003). Bulletin boards are where learners and teachers post and share their messages with others. The advantage of bulletin boards is that the messages can be viewed, shared, and commented on with different people around the world and not necessarily with other learners or teachers, which gives it an extra advantage over email (Beatty, 2003). Email is considered one of the most common activities that learners use on the internet that gives them different advantages like recording both their own messages and those which they receive and communicating with their teachers, peers, and native speakers of the target language (Beatty, 2003). Peterson (1997) further commented that email and asynchronous conferencing are the most common applications of CMC that are found in language classrooms. WebTV, Multi-User domains Object Oriented (MOO), Multi-User Adventure (MUA), Multi-User Domains/Dungeons (MUD), Multi-User Shared Hallucination (MUSH), and Multi-User Game (MUG) are examples of programs involving CMC (Beatty, 2003).

World Wide Web (WWW) resources: the WWW offers both learners and teachers an endless source of authentic materials that include handouts; texts; sound; video; and images (Beatty, 2003). It provides them a natural environment of the language to be taught or learned (Yang & Chen, 2006). Hiple and Fleming (2002) state “The world wide web consists of resources and users on the internet utilizing HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol), a set of rules for exchanging files, including text, graphic images, sound, video, and other multimedia” (p. 5). Mosquera (2001) illustrates that what gives the WWW great importance is that the language used is not prefabricated language that is used in most of the language textbooks, but a real and authentic one. It enhances literacy, interaction, empowerment, and validity in language teaching (Taylor & Gitsaki, 2004). Mosquera (2001) illustrates some features that the WWW offers learners to practice: reading newspapers and magazines online; visiting libraries; accessing tourist information; listening to radio programs; watching TV, and visiting museums. Through the WWW, learners are able to learn and practice all language skills; reading, writing, listening and writing in real-world situations and they can also acquire different knowledge forms (Yang & Chen, 2006). There are many websites that offer materials for learners and teachers. Some of them are commercial and many are free.

Studies on Students’ Attitudes Towards CALL

Several studies have been conducted to assess outlooks and opinions of students’ regarding the utilization of computer-based instruction. Ayres (2002) in his empirical study examined students’ general attitude when it comes to computer-assisted language learning (CALL), their perceived view of its relevancy to their course study. The author analyzes students’ perception of CALL compared with the teacher and the links between perceived usefulness of CALL and the student’s aptitude for computer use, level of their language and their age at UNITEC school of English and applied linguistics (2000). A total of 157 non-native speaker undergraduates coming from 27 different nationalities were asked to respond to a questionnaire that was based on statements obtaining information about learners’ views of how useful they viewed the three programs used and how useful they thought the time spent in the laboratory was. The results showed that the learners appreciated and valued computer-assisted language learning and that the use of CALL with existing programs of study ranked highly by the learners. A high percentage of 80%, 77% and 60% found CALL relevant to their needs, a source of useful information and demanded more use of CALL respectively. In short, the study proved high face validity for CALL in this context. The merit of Ayres’ study is in the fact that “it is a strong argument for the more frequent use of CALL in language courses” (p. 9).

In an American context, at the University of Maryland, Rashed (2008) carried out a case study of six international students in order to assess their perceptions of CALL technology implementation. Given the qualitative overall approach, Rashed opted for insight into self-reported perceptions, interaction with technology tools, and the limitations with which technology could be integrated into the learning goals of an ESL curriculum. The study implemented a combination of small-sample surveys, in-depth interviews, observations and a reflective journal. The class in question was an Intensive English Program that met five times a week. Course content consisted of textbook exercises done in class, supplemented by CD/DVD listening, laboratory and Net-based learning experiences. Lab time comprised online learning and practice of grammar rules discussed in lectures, online listening practice, group work on Web Quest, and visits to ESL sites for the exercises they offered. In general, the research uncovered highly positive perceptions by learners of the technologies deployed to enhance language learning. The main concerns seemed to lie with whether the CALL technologies were sufficiently collaborative, interactive and communicative. In addition, the international students put great store by the physical presence of the instructor as an enabler for relating CALL technology to learning goals.

Chen (2003) carried out a study among EFL learners to investigate their opinions and approaches towards the utilization of computers based on their computer experience in EFL instruction at National Cheng Kung University in Taiwan. The findings of the study showed that the participants significantly exhibited a positive outlook towards the integration of computer systems into the EFL study program that they were enrolled in.

Sum up: Overall then we have not found any studies of student attitude that did not yield favorable attitudes to whatever computer involvement in ELT they had experienced????

Studies about students’ attitudes towards computers in the Arab world

In the Arab world, Bulut and Abu Seileek (2006) worked on learners’ attitudes toward CALL and its connection with the development of four basic language skills (Listening, Speaking, Writing, and Reading). The main merit of this study is its uniqueness from the point of view of its focus on the relationship between students’ attitudes towards CALL and their performance of their particular language skills. The study differs from the existing research that mainly focuses only on the opinion of students thus being one-sided. The study is a mixture of qualitative and quantitative methods of research-based in the context of The Department of English Language and Linguistics at King Saud University in KSA. The data for this study were collected by means of the use of a five-point Likert scale attitude questionnaire for only one of the skills and an achievement test for that particular language skill from 112 students who participated in the course during the First Semester of the academic year 2005-2006. The overall results of the study indicated that the integration of CALL into the curriculum for teaching basic language skills was greatly appreciated and approved by the participants. As for the basic language skills and students’ attitude towards them in terms of CALL application, Listening and Writing appeared to be favored by students in comparison with Speaking and Reading. Such a result of the study is of great interest since its further analysis and study can offer the ways of improvement of students’ attitude towards CALL and its use for the development of two language skills that are the least popular in this relation, Speaking and Reading. Results on the relationship between students’ attitudes toward CALL for specific language and their progress in the development of these skills, however, were not significant. Bulut and Abu Seileek also emphasize that CALL experience has its own idiosyncrasies and its results are dependent upon so many contextual and even personal attributes, such as individual perception of CALL as luxury. A wide range of software was used for the study: electronic dictionaries, electronic books with CD-ROMs, word processors, computer-based exercises (for instance, multiple-choice, filling of the gaps). The weak point of the study is the absence of concrete examples of software used that is justified by the authors’ statement that the research is not aimed at the study of software. Though it is really so, the emphasis on the software could have helped in the analysis of the preference given to Listening and Reading in CALL.

Stevens (1991) also investigated Arab EFL learners’ attitudes toward CALL and found that learners enjoy using computers. This finding was from the survey done by Stevens on selected Arab EFL learners to which he had access. The Arab EFL learners have reported in the survey that computers have improved their English and they looked at computers as an important factor for them to learn English.

With regards to the effectiveness of CALL on EFL students’ achievement and attitude, Almakhlafi (2006) conducted an experiment on elementary-prep school students in the United Arab Emirates. A pre-test and post-test experimental and control group design was adopted and a total of 83 elementary-prep school students (11-13 years old) randomly chosen with an intermediate level of English, participated in the study during the academic year of 2003-2004. The participating students were divided into two groups i.e. the experimental group which had over 43 students, and the control group which had around 40 students. There were four total classes subject to the same conditions of class size, identical textbooks of English, identical level and matching AV aids. Pre-test and post-tests were used to measure the difference in participants’ language competence before and after the study. The materials utilized involved: CD-ROM along with a hardcopy for the 40 students in the control group, EFL skills Development (TM) which had videos along with sound clips, pictures, and CALL for the experimental group.

Specifically, the post-test at the first stage was identical in nature to the pre-test making the assessment of the results more objective, while the second stage, was a 7-points bipolar questionnaire (based on 7-point bipolar probability ranging from, for instance, appreciation to rejection of CALL as a part of the learning experience). The combination of the tests gauged the users’ overall attitudes towards CALL, its utility, the supposed information gain of EFL, along with the intentions towards future utilization of Computer Assisted Language Learning. In all, the data were collected over a period of 5 weeks which seems sufficient in terms of the study duration. A noteworthy variance in achievements was apparent among the CALL users and non-users. The results also showed overall positive attitudes towards CALL use that were forced by the student’s observation of their personal improvement of comprehension and the utility of CALL for more successful completion of course assignments.

The utility of CALL in the student’s future endeavors was documented however such finding could not be generalized since the study has its limitations with regards to other age groups, nationality, and gender of students aside from Arab.

In another study done by Towondrow (1996), a case study was employed to measure the appropriateness of exploratory software exemplified through “guided discovery” at United Arab Emirates University (UAE Uni). The University General Requirements Unit English Programme was designed to provide learning support to all first-year undergraduate students during one semester of their study (fall) in 1996. Students were given 2 hours of computer-based instruction a week in Power Macintosh equipped labs. Open-ended and close-ended questions were used to gather opinions about the attitudes that will lead to the investigation of the appropriateness of CALL for English learning. The results showed that CALL was helpful and classroom-based instruction was reinforced due to it. It was found that 26% of the students considered the courses “difficult’’ that changes their attitudes at times thus resulting in failure to obtain desired progress. It was concluded that this mismatch of software and students could be improved by the teachers’ own participation in CALL and that teachers themselves should be provided with support from directors from outside the class. Thus, the value of the study is its uniqueness in terms of the analysis of the students’ failure to succeed in the use of academic software and its interrelation with the student’s attitude to the courseware. Besides, this study and the previous one analyzed may be considered as mutually complementary based on the notion that the subjects of the first study were male students while the second study focused on female students.

Yushau (2006) conducted a study to examine the influence of blended e-learning on learners’ attitudes toward mathematics and computers at King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM) in Saudi Arabia. Data were collected from 70 Saudi students of the preparatory year program at beginning of the program (pre-program) and at the end of it (post-program). For measuring computer attitudes. Yushau (2006) used the Computer Attitude Scale (CAS) (Loyd & Gressard, 1984). The findings of the study showed that learners at KFUPM in the preparatory year program hold positive outlooks regarding the utilization of computers and believe that computers help them in their study. The results of the study also showed that the Saudi learners want more use of computers in their study.

Al-Shammari (2007) studied Saudi EFL learners’ attitudes towards CALL in an intensive English language program at four campuses (two campuses in Riyadh with separate male and female campuses, Dammam and Jeddah campuses) of the Institute of Public Administration (IPA) in K.S.A to answer five research questions regarding gender, the field of study, English language background, age, and current level of English language study to determine the relationship between learners’ attitudes and these five variables. 1500 random Saudi EFL learners on voluntary participation with 21% representation of females and 78% males were included in cluster sampling and were divided into two groups according to English levels: preparatory and intermediate or elementary, and advanced. The instrument applied was a questionnaire (administered to 587 EFL participants) translated into Arabic with two major sections: 1) demographic information with 10 items and 2) SACALL (The scales of attitude towards CALL) consisting of 30 items with three subscales of attitudes to CALL in the first and second subscale, and attitudes to the CALL Lab adapted from SETA (Educational Technology attitudes subscales) by Pi-Ching Chen. The overall results of the study indicated a positive attitude towards CALL and the software in use, although Saudi females had a more positive attitude towards CALL than males. It is worth mentioning that this finding of the research seems to be the most unexpected one, taking into consideration all previously analyzed surveys and studies that demonstrated the prevalence of positive attitudes among male students in contrast to prevailing negative attitudes of female students. However, the researcher offers no explanation of the reasons why the results of this study differ from other surveys greatly in terms of gender and attitudes to CALL. Perhaps, there is no explanation as the researcher does not put forward any explanation relating to the reasons for the difference of attitudes. Still, this issue should be studied further as it can help improve females’ attitudes to CALL in those educational establishments where they tend to be negative.

A significant finding of Al-Shammari (2007) was the satisfactory attitude towards the CALL system called ‘The New Dynamic English’ that was observed in all IPACALL labs. Previous research does not offer information relating to the students’ attitudes to CALL labs, thus, this is one more merit of Al-Shammari’s study. In addition, the study showed that previous background of English seemed to have no actual effect or bearing on the students’ outlooks towards CALL. Thus, the period of English language learning did not play any role in attitude change towards CALL. However, previous computer knowledge showed a significant attitude change, e.g. more hours of daily use of a computer meant better computer skills and a more positive attitude towards CALL. This finding coincides with the results of the above-analyzed studies (Bush, 1995; Shashsaani, 1997). Again, the study proves that to obtain positive attitudes of students’ to CALL, it is necessary to ensure certain prior experience before college studies and a certain amount of initial computer literacy.

In the above section you have assembled accounts of studies in Arab contexts BUT you need to pick out better what is relevant.

- Some concern Arabs at a level different from yours or in a different kind of university… say less about those and say why

- Some involved intervention/experiments where CALL was specially introduced. We don’t need to hear about the study design and instruments in detail as you are not doing that sort of study

- Highlight instruments used such as questionnaires… anything like you used… were they used as a source by you?

- Highlight results on attitudes (and use, if any) which constitute predictions/hypotheses about what YOU might find

Studies on Attitudes of Teacher

Training appear to be a crucial issue which impacts on EFL teachers’ attitudes to CALL/computers. The present subsection shows the importance of specialized training of pre-service and in-service teachers that are aimed at the improvement of their computer literacy can influence their professional attitude towards computer technologies in the educational process successfully.

Research conducted by Kilic (2001) analyzes the influence of the use of “telecommunication technologies and communicating on computers on pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards what? ” (p. 62) at Indiana University in the fall semester of 1998-1999 academic years at the level of Elementary Science Methods Course. All student teachers from this course were divided into two groups with group A (consisting of 43 students) where the use of communication technologies was integrated; and group B (consisting of 49 students) where telecommunication technologies were not applied. They were asked to respond to a survey adapted from Mitra (1998) administered at the beginning and at the end of the semester by means of pre-test and post-test of the student’s attitudes towards computer technologies. The survey tested two groups on the basis of two subscales: attitudes towards computer subscale (including eight items: attitudes, feelings of being comfortable, apprehensive, or neutral while using computers) and the attitudes towards communicating on computers subscale.

The findings of the research show that the use of telecommunication technologies in this study did not influence students’ attitudes towards computers and their attitudes towards computer-based communication. The studied groups had demonstrated positive attitude towards computers and communicating on computers before the survey and the results remained approximately the same after the survey. The value of this research lies on the context that though telecommunication technologies does not offer dramatic changes of students’ attitudes, it is still possible to find a balance and harmony between personal and educational use of computer technologies by students.

Yildirim’s (2000) qualitative as well as a quantitative study was based on the assumption that positive attitudes towards computers and an increase in computer use was a direct result of increased computer training. The researcher analyzed the effects of a computer literacy course on pre-service and in-service teachers’ attitudes at California State University. The survey also had a goal of examining the changes of attitudes resulting from participation in educational computing class aid to investigate the factors maximizing teachers’ computer use. For the sake of this study, a computer competency survey was distributed among 114 participants (83 females, 31 males) divided into three groups: novice (group 1), intermediate (group 2) and competent (group 3) according to their level of computer literacy. The assessed sub-skills included the following: word processing, presentation of software use, web browsing, telecommunications use, educational software use, spreadsheet use, database management, and desktop publishing. In addition, the study was performed according to three types of attitudes towards computer technologies: anxiety, confidence and liking, following Loyd and Gressard (1984). The data for the study were collected through a pre-test, post-test, and a follow-up study. The results of the pre-test were analyzed using MANOVA, which showed that the competent members of the above-mentioned group 3 demonstrated a significantly higher positive attitude, more confidence and less anxiety than members of groups 1(novice) and 2 (intermediate).

The results of the post-test indicated that group 1 had as much of a positive attitude, less anxiety and more confidence as teachers in group 2 and group 3. This can be explained by the fact that teachers of group 1 gained more from the course in terms of increasing confidence, reducing anxiety and improving attitudes towards computers. The practical value of the analyzed study is in the fact that it demonstrates the importance of educational computing class aid for the improvement of positive approaches of pre-service and in-service educators regarding the general utilization of computers that can be successfully applied for professional purposes.

Kenzek, Christensen and Rice’s (1997) study aims at measuring attitudinal changes in those 9 groups of 118 subjects ranging from novice teachers to teachers having little computer knowledge experienced during their 6 weekly technology training sessions that took place at Texas public school district during 1995-1996 on Macintosh computers. TAQ or “teachers attitudes towards computers” was used to collect data at two levels: 1) by completing both pre-test and post-test questionnaires, 2) by providing further information matching their responses in pre-tests and post-tests. On the whole, the two levels contained about 284 items (e.g. included in CAS, CASL, CUQ, ATCS, etc.). The data were analyzed using 32 Likert scales and Semantic Differential subscales, which were the scales determining the value of an object, quality, etc. in comparison with other objects or from the point of view of contrasting concepts (for instance, good and bad). The data were finally categorized into 8 factors similar to Gardner, Discenza and Duke’s (1993) study and many others. The overall results showed that teachers under technology training reduced their anxieties about computers use and their expectations about the usefulness of information technology increased. Enjoyment and liking measures also rose to positive.

Christensen (2002), in her research, presented findings from a year-long study of a large public elementary school in North Texas, the U.S.A, which has introduced information technology into teachers’ daily classroom practices. In particular, she studied the effects of the Needs-based technique (based on the study of computer anxiety) in the introduction of technology incorporation edification on the outlooks of instructors and learners in this context. For this purpose, a total of sixty (60) teachers from the school and two similar comparison schools in the same district were used as comparison groups and were given two days of instructions and a follow-up training was arranged. In addition, the teachers’ attitudes towards computers questionnaires (TAC Ver.2.21) were used to gather attitudinal data from teachers at the treatment and comparison schools. CASC i.e. computer confidence construct (CASD) was added to the above for completeness, as well as Loyd and Gressond’s CAS, were used as attitude indicators for historical purposes. Similarly, young children’s computer inventory (YCCI that is a 52-item Likert instrument meant for the measurement of children’s attitudes towards computers) components, for example, 1- computer importance 2- computer enjoyment and 3- computer anxiety were measured and utilized. The findings of this study showed that technology integration education strongly influenced teachers’ attitudes towards computers. However, this effect is weaker (although present) on students. It also shows that training enhances better use of computers by teachers, which in turn positively fosters students’ computer enjoyment. Alternatively, a greater positive perception of computer use in the classroom gives rise to higher computer anxiety in teachers (Christensen, 2002). On the whole, the value of the research by Christensen is in the fact that it shows the connection between teachers’ and students’ reactions to technology integration education as mutually dependent. The fact that students’ reaction is weaker than that of the teachers is also significant. It can be explained by the fact that the younger generation has a better awareness of technologies and is more open to innovations than the older generation. Perhaps, students’ initial attitudes towards computers are stronger than those of teachers.

Afshari, Bakar, Luang, Samah, & Fooi (2009) reviewed the pedagogical, psychological and cognitive factors (evaluation, analysis of ICT, etc.) influencing teachers’ decision to use ICT in the classroom. They also suggested a model for the integration of technology into teacher training programs as after Ten Brummelhuis. Thus, the study has practical value. They categorized the factors affecting teachers’ use of ICT into two main types: non-manipulative (which cannot be directly affected towards any change, e.g. age, teaching experience, computer experience or governmental policies, etc.) school and teacher factors and manipulative factors (e.g. attitudes and beliefs or perceptions, and even knowledge and skills). This review of previous studies done by Afshari et al. (2009) showed the interrelation of these two types of factors. To make the integration of technology into the educational process successful, a need of identifying factors, having a plan and vision is emphasized. This can be achieved by means of individual support, intellectual stimulus, working to achieve group goals that should be provided by principals of the schools. Schools should also take their entire community into confidence and should utilize their knowledge and skills for the successful integration of information technology and computers in the educational system. After the implementation of ICT in teacher training programs, teachers should continuously be updated with the current demands in the field through pre-service as well as in-service courses. Thus, the value of the research is that it not only analyzes the factors influencing teachers and their attitudes towards ICT, but it gives practical advice on the improvement of the situation. One more merit of the study that deserves mentioning is the role of principals as active agents, supporters, and providers of ICT at their schools. Thus, the role of principals in the formation of attitudes of teachers towards CALL should be also analyzed in our research.

Studies on Teachers’ Attitude Towards CALL in Arab World

Albirini’s (2004) descriptive exploratory dissertation investigates quantitatively and qualitatively the outlooks of EFL instructors regarding their use of ICT in education in a Syrian high school in Hims during 2003-2004. The study was designed to be carried out using a questionnaire and an interview. The researcher also studied the relationship between the attitudes of the above-mentioned subjects and the following five variables: cultural perceptions, computer attributes, computer access, computer competence and demographic information of the subjects from a sample size of 887, selecting randomly a sample size of 326. This study is based on Roger’s (1983) Diffusion of Innovations and Ajzen and Fishbien’s (1980) “theory of reasoned action”, and the choice of the theoretical background for Albirini’s research seems useful for our study as it shows the way how theory impacts research design. Thus, Rogers (1983: 5) defines diffusion as “the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system”. Since Rogers (1983) singles out such central elements of the diffusion process as communication channels and social systems, his theoretical data can become useful for our research. As for Ajzen and Fishbein’s Theory of Reasoned Action, it can also become a useful theoretical ground for practical research. For instance, Ajzen & Fishbein (1980) single out two factors that help to explain behavior (personal factor and social influence). In other sources analyzed in this review (Shashsaani, 1997; Bush, 1995), practical support of Ajzen and Fishbein’s theory could be found. Thus, the Theory of Reasoned Action can be valuable for our research as well.

Albarino collected the data in two stages using a survey questionnaire and a telephonic interview. The questionnaire on the computer and computer-related techniques in education was distributed to 326 EFL teachers selected through a “table of random numbers” (arbitrary selection) for which the response rate of 98% was obtained. Finally, a sample of 314 responses was analyzed using SPSS 12 statistical package. The second instrument seems to be interesting in terms of its originality. Stage two was based on a semi-structured interview consisting of two stages: first, a telephonic interview for preliminary information and for arranging an interview and then the 20-30 minutes audio-taped interview “information-rich” from a population of 15 teachers (those who had demonstrated strong reactions on the following variables: computer competence, computer access, and computer training) followed the survey to seek explanations for attitudinal motivation. The results of the study indicated that instructors’ observations of the social importance of computers lied amid impartial and affirmative. The quantitative data (questionnaire) highlighted the overall positive perception of computer use as the means that develops skills privileged people have. The subjects testified that it positively affected their way of living by making them choose a high standard of lifestyle and it made life easier in general. The three negative factors, however, included: social concerns to be addressed before ICT implementation, the fast proliferation of computers, and lack of software representing Arab culture and identity. The qualitative part of the research revealed favorable factors as enhanced “cultural education” and extra-curricular knowledge of the outer world and cultures. Unfavorable factors came down to a gradual loss of social interaction and no or lesser representation of Arab culture and identity. They were also concerned about the immoral aspects of computers. But on the whole, it was observed that teachers’ attitude was positive of the relative importance of ICT in these educational institutes.

Abu Samak(2006) in her quantitative research, which can be called a copy of extinction to Albirini’s (2004) work, explores elements that can affect outlooks towards information and communication technology (ICT) by Jordanian EFL instructors. She also looked into the extent to which there was a link between the Jordanian EFL teachers outlook towards ICT with a number of related variables, which includes the instructor’s opinion on the attributes of ICT, related social perceptions of ICT, level of access to ICT along with competence in making use of the ICT, in addition to a myriad of characteristics that are attributed to the teachers but related to demographic information. For this purpose, adopting a multi-part survey in Arabic used by Albirini (2004) and following Roger’s (1995) ‘’Diffusion of Innovation Theory” ’and Ajzan and Fishbein’s (1980) ‘’Theory of Reasoned Action” results were obtained from a target population of 760 Jordanian EFL teachers (357 males and 403 females) in the first and second district of Amman during the academic year 2005-2006 and a sample size of 380. Through a cross-sectional method to gather data on EFL teachers collected at a single point and administering a pilot study of a sample of 15 (males and females). The ICT survey of EFL teachers in Jordan, in particular, focused on the following:

“1-Attitudes towards ICT, 2- perceived computer attributes, 3- cultural perspectives, 4- perceived computer competence, 5- perceived computer access, and 6- teacher characteristic” (Albirini 2004). The results of the study were consistent with the theoretical frameworks applied and previous work by Albirini (2004) too. The results showed that many factors like instructors’ encouraging outlooks and their stout insights of the characteristics of ICT, the rigorous required in-service drill ICDL certificate and added workshops presented by JMOE, and the high level of computer competence of EFL Jordanian educators, all played a significant role in an accelerated adoption of ICT by teachers. Moreover, it was also found out that EFL teachers in Jordan were not comfortable with limited time in the school day with teaching through computers as they thought it affects computers negatively.

Al-Khatani (2001), in his qualitative as well as quantitative study, investigates how CALL is being used by EFL instructors at four government-funded universities in Saudi Arabia: King Saud University (KSU), Imam Mohammed Bin Saud Islamic University (IMIU), King Khalid University (KKU), and King Fahad University Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM).

The status of CALL at University level EFL teachers in this context was studied with particular focus on:

- access to CALL,

- CALL practice,

- teaching methods and beliefs about CALL usage.

The qualitative data for this study were obtained from three primary sources: 1 – a questionnaire, 2 – three case studies and 3- personal interviews with thirteen members of Saudi EFL teaching staff. One of the merits of this research is the analysis of the case studies since it is the only research among those analyzed in the present Literature Review that makes use of such instruments for research. The questionnaire was used to collect data from 91 EFL faculty members and departmental chairmen at the four Universities, while purposeful sampling techniques were also used to select three participants for the case studies who were an assistant professor and two instructors using CALL more than others. The interviews of chairmen, a dean, CALL coordinators, and campus computing directors and analysis of CALL-related documents were utilized to get supplemental data. The findings of the study regarding CALL practices in this context showed that CALL is used neither in the English departments at KSUCOA nor in the English Language and Translation Institute at KKU, with the exception of a few teachers with occasional use, while at IMIU, it is used to overcome the fear of the technology. KSUCLT uses computers to teach basic literacy skills and they are used for instruction but actual use in class is word processing; the use of computers with the same purpose is observed at KFUPM as well. The four Universities also use computers to produce instructional materials alone. The only computer tools used for EFL Instruction were drill-and-practice, tutorial and processing programs. Thus, it can be observed that there is inconsistency in the use of CALL at the studied universities. On the whole, the research shows that the level of CALL is very low in the analyzed educational establishments. In order to improve the current situation, it is necessary to make investments in the development of a technical basis for CALL and improvement of computer literacy of both teachers and students.

Besides, a high percentage of 82% respondents felt that CALL could be utilized effectively to enhance the quality of language teaching and learning, while 78.4% believed that CALL experience could help them succeed in today’s modern era and 73% believed that CALL helps language teachers to better deal with students’ individual needs (Al-Khatani, 2001). Though the subjects of the research mentioned disadvantages of CALL (for instance, improper content of software abusing Islamic religious view), in general, the findings of the beliefs about using CALL in EFL Instruction showed that respondents generally held positive outlooks regarding the utilization of computers for EFL.

Finally, the last two valuable ideas concerning CALL and Arabian teachers (though it can be characteristic of teachers of other nationalities as well) are that EFL teachers fear that they may be replaced by computers sooner or later and there is the fear of students becoming too dependent on technologies in education. Walker’s research is significant in this relation.

Walker (1994) published a brief survey carried out at the English language Centre (ELC) at King Fahd University, K.S.A, which investigated teachers’ attitudes towards CALL. A questionnaire based on 14 open-ended questions was distributed to all 64 male members of the faculty with half owning their own computers. A response rate of 97% showed a positive response towards CALL. The majority found CALL beneficial and a useful tool, only a minority feared computers replacing them. The results indicated that a useful application of computers is in teachers’ hands and that students have realistic expectations from the teachers. A ratio of 50:50 was observed on the issue of students becoming too dependent on computers. The majority takes computers as inevitable in the classroom and believes that even if lessons are poor, there is always something new to learn for students. An overwhelming majority of teachers recommends the use of computer games contrary to drill and practice for language learning.

Al-Asmari (2005) applied a similar methodology to Albirini, but to study a different aspect of computer use in education. His work primarily investigates the use of the internet at Saudi Arabian colleges of technology situated in Riyadh, Abha, Jeddah and Dammam during the academic year of 2004-5, by the EFL teachers. The research also looks into the relationship existing between teachers’ use of the Internet and a set of five variables: personal attributes of teachers, the accessibility of the Internet, teachers’ perceived expertise in computer use and the Internet, and the use of the Internet as a tool for instructions. He also applied Roger’s (1995) model of Diffusion of Innovations and applied both quantitative and qualitative methods to collect data. Such popularity of Roger’s model proves its usefulness for such a type of research on attitude. Thus, a questionnaire and a telephonic interview were used to collect data from a sample of 203 EFL teachers over a period of four months. A response rate of 91.1% was obtained through personal contact with respondents. Later, a 10-20 minute interview was arranged telephonically from 15 out of 84 teachers (51%) and it was audio-tapped. The interview was based on three questions based on the need for advocacy of the Internet, factors limiting the use of the Internet and the proper use of the Internet for EFL instructions. An SPSS 12 analysis of the data showed teachers’ positive inclination towards the use of the Internet in educational instructions. A very strong relationship was also observed between teachers’ use of the Internet and independent variables mentioned above. The follow-up interview results were also used to comment on observations obtained from the questionnaire and positive attitudes towards the use of the Internet in educational instructions were observed. This was, in turn, attributed to the advantages of Internet use, like time-saving, improving quality and quantity with easy storage and retrieval, etc, thus implying its use in educational instruction. The presence of positive attitudes of teachers towards the use of the Internet is a valuable finding since other studies reviewed in this paper mainly tackle the use of software, not the Internet. Due to Al-Asmari, a fuller picture of attitudes of teachers towards technologies and technology-based education is created.

Alaa Sadik (2005) conducted another study in one more middle eastern region to assess the attitudes of Egyptian instructors regarding utilizing computers for instruction along with their personal use. The research also focused on validating an Arabic form of the Computer Attitude Scale (CAS), which was originally introduced by Lloyd and Gressard (1984), and the Attitudes towards the Use of Computers in Schooling, created by Troutman (1991). The study had over 443 participants who were instructors in public schools from the southern districts of Egypt. The research’s findings concluded that the majority of the teachers had a positive outlook regarding the utilization of computers in instructions. The demographic variables that were analyzed were closely linked to the instructor’s perceptions of computers. Male teachers seem to have a more positive perception of computers than their female counterparts. The teacher that had prior experience with computers also showed encouraging attitudes towards computer-based instruction. Sadik (2005) also looked into the usage of computers during schooling in terms of the instructors’ outlook on the matter and concluded that teachers saw computers as a useful tool for instruction.

Computer Attitude Scales

In this section, two separate efforts are discussed at developing study instruments to measure attitudes towards computers themselves. Selwyn (1997) did the work in a Welsh university preparatory context followed seven years later by Roussos (published online in 2004 but formally published only in 2007) at the University of the Aegean. Selwyn (1997) constructed an attitude scale in order to fill the gap in the assessment of college preparatory student (year levels 12 to 14, age 16 to 19 years) attitudes towards computers. The urgency for filling this investigative gap was underlined by the fact that employers of post-compulsory education graduates (or university, since the test construction took place in a Welsh setting) use computers virtually everywhere in business. Since businesses expect university graduates to already be IT-literate, Selwyn realized that educators could fine-tune their IT courses better if they knew what student attitudinal baselines were.

To reinforce this rationale, Selwyn cites Wondrow (1991) who insists that assessment of student attitudes should be one of the central criteria for evaluating IT courses and managing curriculum changes. An equally important consideration, perhaps, is that level 12 to 14 students in the English system are free for the first time to choose what courses they might take preparatory to completing the requirements for a university degree. Such attitudes as they have might immediately impact enrolment in IT-heavy courses, as well as skill sets necessary for employment in the future.

For his framework, Selwyn employed five constructs as follows:

The theoretical rigor underlying this effort to develop an attitudinal scale regarding computers is evident in the author having based scale construction on the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1993), the Tripartite Model of Attitude (Kay, 1993), the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1998), and the attitude paradigm proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975). The author constructed the first set of items by formulating original ones and replicating others still applicable from the work of previous researchers in the field. All in all, the preliminary items numbered 49 and were formulated as five-point Likert scales of agreement-disagreement.

The study retest yielded satisfactorily high Cronbach’s α of between 0.79 to 0.93 for the four factors and 0.90 for the overall scale. These suggest very good internal consistency for the scale. Re-administering the cut-down study instrument to the original sample of 226 students after a fortnight had elapsed revealed an excellent Pearson’s r of 0.93 for test-retest reliability, which is statistically significant at p < 0.001. This entire means is that the statistic was calculated only for the items that were retained. Lastly, the author fortifies his claim to an eminently usable scale by supplying a measure of criterion validity, related to the question of whether the study measures what it purports to. For this purpose, the retest stage included an inventory of activities or end-uses to which university preparatory students put home or school computers. Since the items were formulated with an ordinal scale of frequency, Spearman’s rank-order correlation was used to assess construct validity. The outcome seemed satisfactory: p < 0.001, correlation for the overall scale rs = 0.74. In net, Selwyn can claim a potentially very useful and valid scale for assessing prep student attitudes prior to their embarking on IT-supported courses at grades 12 to 14. Knowing how each student stands should then permit teachers to assess and adjust for individual disadvantage, as well as to characterize each incoming cohort by the usual parameters of gender, social class, and where secondary education was taken. The author claims the 21 items can be administered in just five minutes but one must caution that speed and understanding may not hold in ESL cultures.

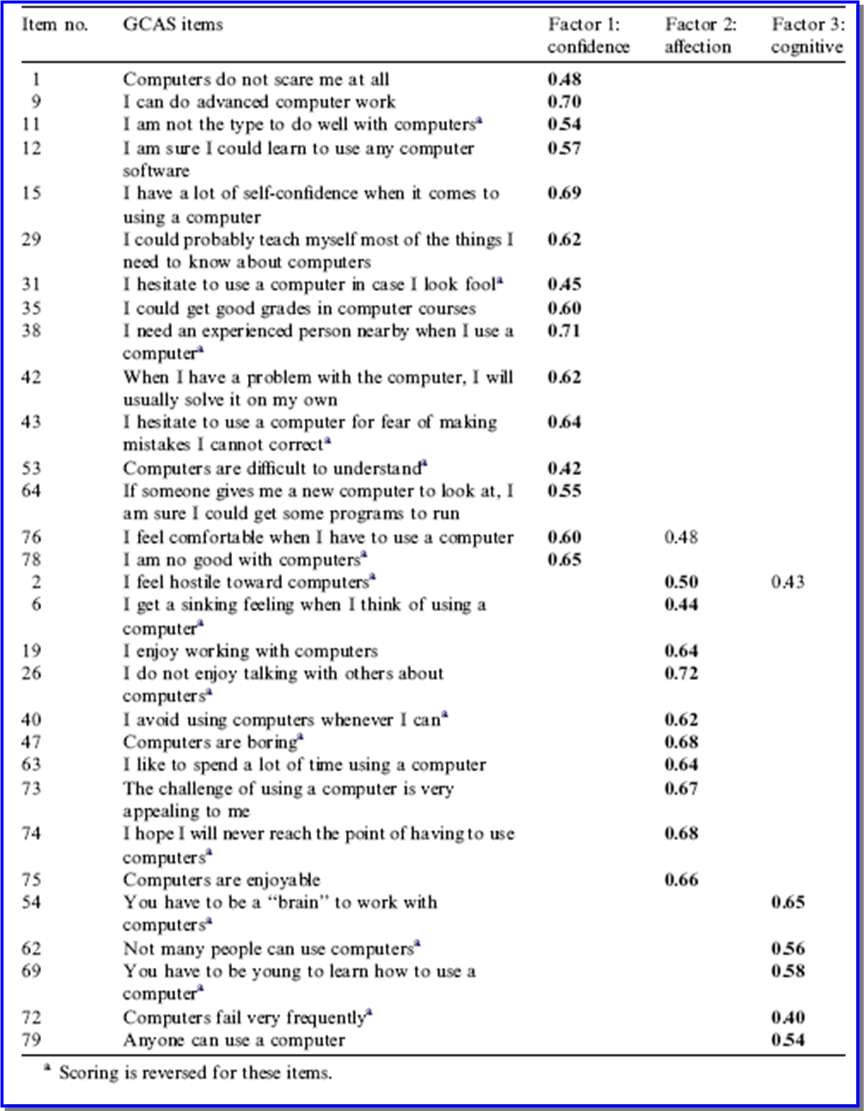

In turn, Roussos (2007) essayed a similar effort to formulate and quantify psychometric properties of a localized computer attitudes scale. Though the author acknowledges Selwyn as one source and the structure of the studies parallels each other – after all, the mechanics and rigor of test construction should differ little – the Greek effort is in many ways more thoroughgoing.

Having been done much later, the Roussos scale benefits from other work carried out as late as 2000 (Richter, Naumann & Groeben, 2000). Nonetheless, the latter effort is similar for relying on Azjen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour (1988), employing a five-point Likert scale of agreement-disagreement, incorporating the core set of four constructs, reversing polarity for certain items so as to avoid ‘run on’ bias. Roussos was also careful to formulate new items besides incorporating what seemed applicable from studies that had been conducted and published as early as 1970. All in all, the first version had a total of 79 items. Consideration of psychometric properties and the sub-populations of interest eventually reduced this to a handier set of 30 items.

On the face of it, the GCAS comprised just three subscales which consisted of cognitive, confidence along affection which was short of the four Selwyn had. In reality, the former did have sub-scales measuring supposed worth, supposed control and behavioral outlooks regarding the utilization of computers. The whole effort was meant to address a stumbling block in efforts by the Greek government to attain goals for familiarisation, acquisition, and adoption of computers and Internet connectivity at the primary and secondary levels of education no later than 2006 (Greek Ministry of National Education and Religious Affairs, 2003). Along the way, it was discovered that teacher confidence was degraded by lack of knowledge (Roussos, 2002; Vryzas & Tsitouridou, 2002) and negative student attitudes also contributed to failure for a number of IT initiatives in the classroom (e.g., Roussos, Tsaousis, Karamanis, & Politis, 2000). Given the policy context, Roussos focused the study on primary and secondary education. This means that the Greek study is not even perfectly comparable with that done by Selwyn.