Each language in the world demonstrates features of a living organism, as some of them evolve and take new forms, while others gradually disappear and die. Arabic remains one of the most spoken languages globally, and there are several varieties of it. The diversity of Arabic is determined by its broad geography, as each nation adds a particular touch to it. However, there is the Modern Standard variety, the purpose of which is to ensure quality communication in the Arabic world despite regional differences. It derives directly from Classical Arabic, which serves as an area of intense interest for researchers attempting to determine whether it can be considered a dead language. This paper explores the differences between Classical Arabic and its modern varieties, comprising Modern Standard, Moroccan, and Egyptian ones, proving that it is not yet a dead language.

Review of Literature

Relevant, up-to-date sources are the cornerstone of every research, allowing for a comprehensive examination of the matter at hand. The Arabic language is quite prominent in the contemporary environment, which is why there is a substantial amount of studies devoted to it. The book Arabic as one language: Integrating dialect in the Arabic language curriculum was published by Mahmoud Al-Batal in 2017. The book discusses the traditional approach to Arabic studies, according to which students begin by learning Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and then transition to the spoken variety of the language. Al-Batal (2017) argues that this method is inefficient, as it does not fully reflect the nature of communication in Arabic, leaving students with insufficient skills. The book explores Arabic dialects alongside the Modern Standard variety, emphasizing their importance in the contemporary environment. Overall, Al-Batal (2017) presents an interesting point of view, allowing readers to compare dialects and MSA. The findings appear useful in the context of Classical Arabic studies, as well, since MSA is its direct derivative, serving as the bridge between the Qur’an tongue and the language of the people.

Modern Standard Arabic remains an integral means of communication. Its objective is determined by the necessity to unite geographically and linguistically dispersed people of the Arabic world and ensure their communication. As a result, the notion of diglossia has become a prevalent phenomenon among native speakers of Arabic. Al Suwaiyan (2018) puts this matter in the focus of a research article published in the International Journal of Language and Linguistics. This study discusses the origins and aspects of diglossia, which consists of the fact that one country adopts at least two Arabic language varieties. Al Suwaiyan (2018) presents valuable examples of differences between dialects, comparing them with MSA, and tracing the tendencies back to Classical Arabic. Egyptian and Moroccan varieties are examined, as well, highlighting this article’s usefulness in the context of the present study. Generally, one may observe the tendency dictating that dialects and diglossia remain the primary areas of interest for linguists exploring the peculiarities of Arabic.

The evolution of Arabic is often examined in its comparison with Latin and other dead languages. Tomasz Kamusella, a professor at the British University of St. Andrews, proposes an in-depth examination of the issue in his article published in the Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics. The author provides a comprehensive historical overview of Arabic’s evolution, comparing its classical form with other sacred languages, such as Hebrew of the Torah, Latin, and Greek. Kamusella (2017) explains the historical processes at length, which contributed to the good overall preservation of Classical Arabic while adding background for its transition to MSA. Next, the author analyzes the phenomenon of diglossia, which one of the distinct features of the Arabian-speaking world, while examining the possibility of triglossia. In this case, MSA is used in written forms; dialects prevail in verbal communication, whereas European languages, namely English, dominate the professional environment. Kamusella’s (2017) findings appear relevant in the context of the present study, as they provide a clear framework, explaining the evolution of Arabic from its early documented stages to the present in parallel with Latin.

At the same time, modern technologies and communication means serve as valuable sources of information. However, critical thinking must be applied to the Internet-based data, as not all sources can be deemed credible. Encyclopedia Britannica is a perfect example of a valuable research database, containing useful examples and quality visuals. While its materials cannot be used for in-depth analyses of the matter, it helps establish the study’s historical and geographical contexts. Haneen Abu Al Neel (2019) has prepared another useful article for the Arab American community website. It explores the origins of Arabic, tracing it back to merchant times and explaining the paradigms of Arab migration across the Middle East. Besides, some peculiar aspects of the Arabic language are mentioned, providing the reader with the general outline. While the MustGo website is dedicated to travel, it contains an interesting outline of Arabic. Its value within the framework of the present research paper consists of large databases describing the details of the most prominent Arabic dialects. Such sources allow for a clear understanding of the research context, making it possible to provide the general picture before delving into the research of Classical and MSA Arabic particularities.

General Characteristics, Geographical and Historical Context of the Arabic Language

The history of the Arabic Language includes centuries of active development and migration, spreading it across the globe and creating new dialects. Al Neel (2019) mentions that the total number of languages on Earth is between three thousand and eight thousand, and Arabic deservedly occupies a position of paramount importance on the list. While some languages’ origins remain a matter of theory for linguists, it appears possible to trace their evolution through the development of peoples who speak it. Al Neel (2019) emphasizes the connection between the national identity and languages, as they “build much more than just words, they construct a worldview” (para. 1). For example, structural inter-language similarities have a profound influence on people’s attitudes and behaviors within society. Accordingly, as Arabic spreads worldwide, acquitting new forms and dialects, this theory suggests that its native speakers share inherent mindset similarities, including values and worldviews.

The primary spheres of activity of each nation shape the direction of their languages’ evolution. Al Neel (2019) says that Arabs were skilled merchants, and efficient trade was their primary income source. Therefore, Arabic nations remained in close contact with the rest of the world, influencing one another’s languages. Arabic roots used to denote commonly traded items in the previous centuries can be found across a range of European and African languages, including Spanish, Italian, and Swahili. As Arab merchants traveled through the world, new trading centers appeared, and the Arabic world gradually expanded. As its geography became wider, each subgroup of the Arabic world began to show a certain level of independence in terms of linguistic evolution. Nevertheless, as is the case with nearly all languages, it is usually possible to trace the entire variety of forms and dialects to one source. Al Neel (2019) refers to the example of Sanskrit being the universally known ancestor of the Indian subcontinent languages within the Indo-European family. It appears possible to examine Arabic within a similar historical framework.

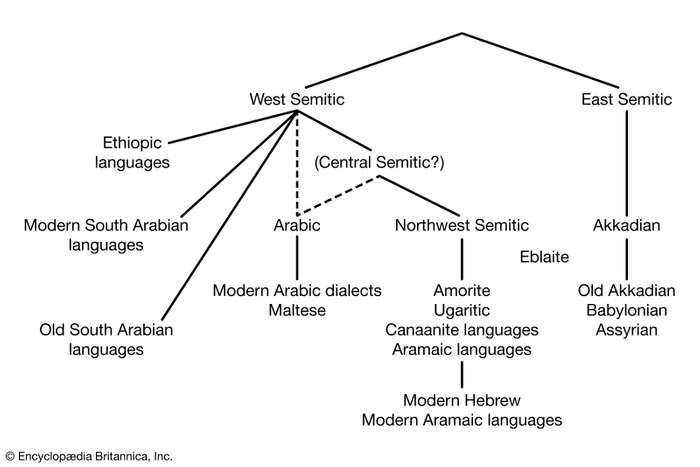

As a matter of fact, all world’s languages are divided into large groups, or families, on the basis of their origins and geography. Contemporary linguists attribute the Arabic language to the Afro-Asiatic language group (Al Neel, 2019). Within it, there is the Semitic family, which has prevailed in the Middle East for over four thousand years. As shown in Figure 1, this family has comprised a large number of prominent languages throughout history. As far as contemporary languages are concerned, Modern Hebrew and Arabic can be considered as the most prominent examples. However, Figure 1 comprises many other languages and dialects, demonstrating the historical importance of the Semitic family. Nations that speak these languages have played crucial roles in the world’s development, including trade, scientific research, and culture. Accordingly, Arabic is a language of global importance, adding particular interest to the studies related to it.

Arabic, among other Semitic languages, is particularly prominent in the Middle East. According to Al Suwaiyan (2018), the total number of its native speakers is over 250 million people. It is important to note that, in some areas, Arabic is spoken only by some portion of the population. For example, Moroccan Arabic is used alongside French and one of the languages pertaining to the Berber family of the Afro-Asiatic group (Al Neel, 2019). The Arabic alphabet contains twenty-eight unique letters, using a particular type of writing. Al Neel (2019) writes that some of these letters are non-existent in other languages, which contributes to the uniqueness of Arabic. The letter “daad,” written as ض, is particularly difficult in terms of pronunciation for foreigners aspiring to learn Arabic Neel, 2019). However, it is broadly used in a variety of words by native speakers. For them, it serves as a symbol of pride, highlighting their linguistic identity. Therefore, Arabic is a highly unique language, which contributes to its role as an interesting study subject. Placing it in a historical and geographical context allows for a better understanding of the matter.

Classical Arabic Language

As stated previously, each language undergoes a complex process of constant development throughout all stages of its existence. As a result, they acquire new forms, which correspond with the changes in setting and the speakers’ mentalities. The Arabic language has followed a similar path, and some of its earlier forms are properly documented. It is characterized by a large number of varieties, and historical, Classical Arabic (CA) is one of them. Al Suwaiyan (2018) refers to CA as the language of “the Qur’an, poetry, and Old Arabic literature, as well as the language, originated by early Arabic grammarians.” (p. 229). In other words, unlike previous forms of Arabic, CA has been preserved through an important piece of literature and documents, which have remained relevant until today. CA represents the form of Arabic, which was in use about fifteen centuries ago in the Arabian Peninsula, namely the territory of Hijaz (Al Suwaiyan, 2018). Evidently, the Qur’an has played a role of paramount importance in preserving the high status of CA through the ages.

In fact, Islam has had a major impact on the language, as researchers distinguish between its two primary eras. Pre-Islamic CA was used in poetry in the sixth century before being replaced by the post-Islamic variety, which was used for the Qur’an (Al Suwaiyan, 2018). In the 800s, prominent Arab researchers established the grammatical paradigm of CA, which contributed to its preservation, as well. This achievement is, indeed, admirable, as there were little or no languages with such a level of documentation at the time, Latin being the obvious exception. Moreover, Classical Arabic is often compared to Latin due to apparent similarities in the level of status and utilization. The languages of Holy Books are always viewed as sacred, as is the case for Latin and the Holy Bible, Hebrew of the Torah, and Greek in Byzantium (Kamusella, 2017). Following the tendencies of secularization and the necessity to make Holy Texts readable for regular people, the aforementioned books have been translated into vernaculars or common languages of the general population. Accordingly, as the Churches began to speak the same languages as the congregations, the importance of sacred tongues diminished.

Nevertheless, Arabic did not use a similar paradigm, thus retaining its status for a longer period. According to Kamusella (2017), “the unity of the holy language of the Quran with its script is underpinned by the strong normative insistence among Islam’s faithful that religion and politics are inseparable” (para. 12). In other words, political leaders of the Arab world also played the roles of spiritual mentors for their people. For example, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire also was the Caliph for all Muslim people (Kamusella, 2017). This model accounted for the better preservation and wider use of CA throughout the Arabic world. However, the tendency did not last past the 1920s as the secularization movement prevailed in Turkey (Kamusella, 2017). Consequently, while the influence of Islam on people’s lives remained considerable, it was not as strong as previously on all levels of national and personal activities. Following this development, people began to speak slightly different languages in the course of everyday communication. Therefore, Classical Arabic lost its importance in informal and interpersonal relations, remaining the primary language of religion and formal communication, and the phenomenon of Arabic diglossia appeared.

Modern Standard Arabic Language

The Modern Standard Arabic language appeared in the 20th century following the secularization tendencies described in the previous section. By that time, the Muslim world was led by the Turkish-Ottoman Empire, which was a major player in the global political arena. Furthermore, as mentioned prior, the Sultan was considered the spiritual leader of all Islam, and his role was similar to that of the Pope of Rome for Catholic Christians (Kamusella, 2017). However, the Ottoman Empire began to lose its power rapidly under the pressure of Europe and Russia. As a result, the secularization movement succeeded within the country, transforming it into the Turkish Republic, which inevitably affected the entire Arabic-speaking world. Consequently, appeals for reformation became heard across these countries, calling for the modernization of Islam and the language. The Arabian world saw a surge of influence of Western ideas, principles, and philosophy, but the preservation of the Arabic language was always a priority (Kamusella, 2017). Numerous works were translated from French and English into Arabic, and Egypt was in the vanguard of this process.

Accordingly, the language had to undergo profound transformations along with society and the political landscape. Close contacts with the Western civilizations entail an increasing number of neologisms, which permeated all levels of communication in Arabic (Kamusella, 2017). In order to transmit the ideas of Western philosophy to Arab communities, it was important to make them understandable by everyone. At the same time, French and English languages and ideas were seen as inherently inferior to the language of the Qur’an (Kamusella, 2017). In addition, several areas, which had previously been controlled by the Ottoman Empire, were under the influence of different European nations, which deepened linguistic differences. According to Al Suwaiyan (2018), in order to have the needs of the Arabic world met, Modern Standard Arabic was developed in the 19th-20th centuries. It is considered to be the modernized version of CA, which ensures international communication between Muslim people without compromising the sacred status of the Qur’an language (Al Suwaiyan, 2018). Since then, this variety of language has been used in formal communication, media, and governmental speeches, making it the lingua franca of the Middle East.

MSA is often examined in relation to its particular features, as compared to CA. Indeed, the modern version updated some linguistic forms in order to facilitate Arab countries’ incorporation into the global political landscape. However, research suggests that it can be seen as the natural evolution of CA rather than a new communication mode (Al Suwaiyan, 2018). In fact, MSA and CA share similar phonology, meaning that the updates did not concern the way the language should be pronounced. Al Suwaiyan (2018) states that the modern variety mainly follows its ancestor’s paradigms of syntax and morphology, as well. The primary differences occur at the level of vocabulary, as MSA has adopted a large number of neologism, phrases, and calques from its European counterparts. In addition, the way in which the phrases are arranged within an Arabic sentence, do not always correspond with the rules of CA (Al Suwaiyan, 2018). In other words, while the basis of MSA syntax was preserved, it still had some alterations, most of which were heavily influenced by the European languages.

Modern Arabic, being uniform for all countries in which it is used, follows the typical structure of Semitic languages. Each Arabic word consists of two parts: a typically three-consonant root accounts for the lexical meaning, while vowel patterns provide grammatical meanings. For example, I suggest that we put an example of Arabic words here to demonstrate the pattern in practice. Traditionally, nouns have a three-case declension paradigm, which, however, is no longer used in colloquial dialects. I suggest that we put an example of Arabic words here to demonstrate the pattern in practice. As far as Arabic verbs are concerned, they are all regular in conjugation, having two tenses. The perfect tense is formed with suffixes and usually serves to refer to the past, whereas the imperfect one indicates gender and number and refers to the present and the future. I suggest that we put an example of Arabic words here to demonstrate the pattern in practice. Gender differentiation is one of the differences between CA and MSA, as the former did not have it.

Despite the uniform nature of Modern Standard Arabic, its use is limited to formal and written communication. Kamusella (2017) writes that the standard and Qur’an forms of Arabic have not existed in the native speakers’ daily communication for a long time. Instead, vernacular forms prevail in personal communication, as people consider them more convenient and better adapted to today’s requirements. In fact, the difference gap between MSA and colloquial dialects is colossal, but an educated person in the Arabic-speaking world is expected to know both varieties (Kamusella, 2017). Moreover, a single occurrence of colloquial phrasing and syntax will be seen as a vulgarism, demonstrating one’s poor education. Moreover, Kamusella (2017) states that such a mistake can be a sign of disbelief, violating the immaculate nature of God’s language. This tendency has appeared due to the objective of preserving the purity of the MSA, which is a direct descendant of the language of the Qur’an. Overall, MSA remains the essential instrument of formal international communication in the Arabic world, but it exists in a strict parallel with colloquial dialects, which vary depending on geographical factors.

Moroccan Arabic Language

As established through the previous research, dialects play a crucial role in the Arabic language. While the use of MSA is limited to formal, written communication, daily exchanges occur exclusively in contemporary colloquial variations of the language. Moroccan Arabic is an excellent example of such a dialect, as it is representative of the whole Maghreb variety group. This term refers to the colloquial forms of Arabic adopted in the Northern part of Africa. The list of Maghreb countries includes Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. However, while each of them uses their own version of Arabic, the vast majority of elements are shared between these dialects, and the Moroccan variety demonstrates the primary aspects of Maghreb. In fact, these countries exist in a peculiar linguistic environment, as they experience a strong influence from other languages, namely Berber and French. Therefore, it is logical to expect a significant amount of neologisms borrowed from these languages.

Moroccan dialect of the Arabic language is a unique variety of language due to its particular nature. As a matter of fact, while it is representative of the regional forms, it is practically unintelligible even for native Arabic speakers outside of Maghreb (“Arabic (Moroccan Spoken),” n.d.) The total number of native Morrocan Arabic speakers is over twenty-one million people, and nineteen million of them reside in Morocco (“Arabic (Moroccan Spoken),” n.d.) In this country, as well as Tunisia and Algeria, MSA remains the official language, but, as discussed previously, its use is limited to formal communicative situations. Tunisian and Algerian varieties exist, as well, but the number of their speakers is incredibly low, as compared to the Moroccan dialect. Therefore, a practical examination of Moroccan Arabic will provide a comprehensive understanding of Maghreb regional particularities.

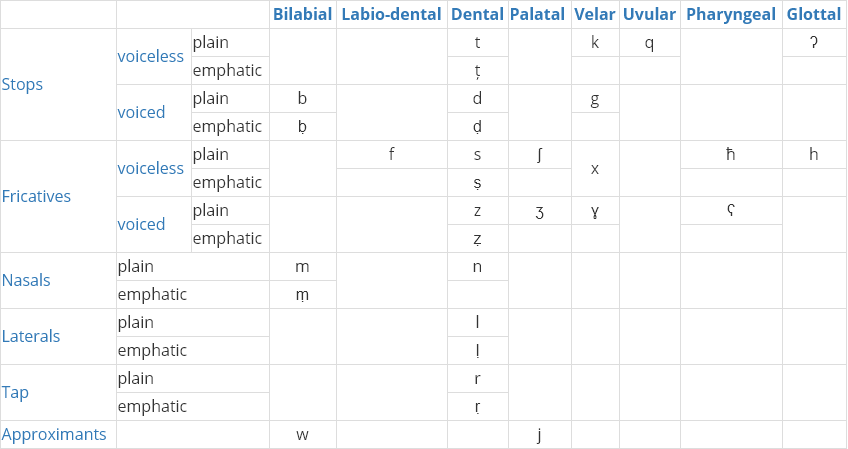

As far as phonology is concerned, Moroccan Arabic has six vowel phonemes, which account for the word’s grammatical meaning. Five of them are short, and one is long, as presented in table 1. At the same time, the number of consonants is equal to thirty-one, and they determine the lexical meaning of lexemes. The system of consonant phonemes in the Moroccan dialect is presented in Figure 2. Moroccan Arabic has lost the interdental consonants /θ/ (as th in thing) and /ð/ (as th in this). However, the “opposition between voiceless, voiced, and emphatic stops and fricatives” has been preserved (“Arabic (Moroccan Spoken),” n.d., para. 13). Another difference from MSA consists of consonant cluster and double consonant use at the beginning of syllables in Moroccan Arabic.

Table 1. Vowel Phonemes of Moroccan Arabic (“Arabic (Moroccan Spoken),” n.d.).

There is a large number of differences between MSA and Moroccan Arabic, which lie in the areas of grammar and vocabulary. Moroccan nouns do not carry the category of case, and their plural forms are composed by the suffixes –in or –at, which are added to the root of the word. In addition, Moroccan verbs are marked for gender, accounting for another difference with MSA. The comparison of basic phrases in Moroccan Arabic and MSA is presented in Table 2. While the dialect shares its core vocabulary with the rest of Arabic varieties, the heavy influence of other languages resulted in a large number of borrowed roots and lexemes. For example, Moroccan uses such words as neggafa (wedding facilitator, from Berber), forchita (fork, from French), and simana (week, from Spanish). Overall, it is possible to observe a tendency toward the facilitation of communication in Moroccan Arabic, as words lose complicated grammatical categories present in MSA.

Table 2. Moroccan Vocabulary as Compared to MSA (“Arabic (Moroccan Spoken),” n.d.).

Egyptian Arabic Language

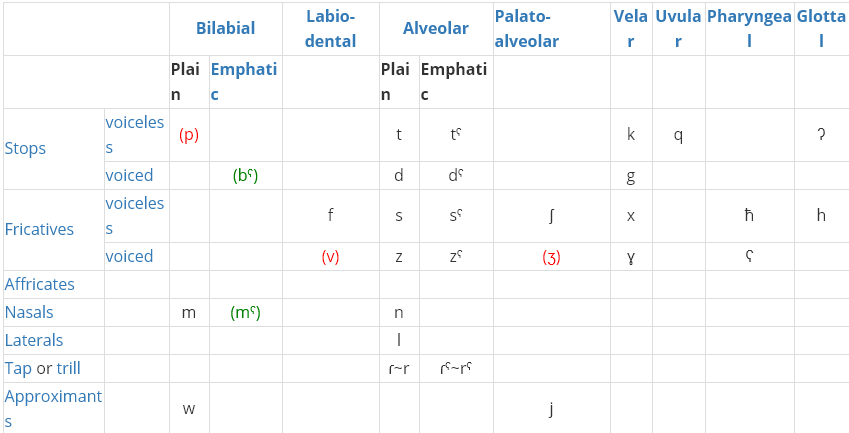

Unlike the Moroccan dialect, Egyptian Arabic is understood in the majority of Arabicphone countries, as this country dominates the cultural landscape. The majority of films, novels, comic books, and TV shows are made in Egyptian Arabic, making it one of the primary dialects (“Arabic (Egyptian Spoken),” n.d.) Accordingly, students learning Arabic as a foreign language usually opt for the Egyptian colloquial variety. Its phonetic structure varies greatly from other forms of the language, as it has more vowels, as presented in Table 3. Additionally, short /i/ and /u/ sounds are omitted when another vowel is added to the word form, while diphthongs /ay/ and /aw/ present in MSA transform into long vowels in all situations. Simultaneously, the consonant system of Egyptian Arabic demonstrates fewer differences from MSA, as shown in Figure 4.

Table 3. Vowel Phonemes of Egyptian Arabic (“Arabic (Egyptian Spoken),” n.d.).

As far as grammar is concerned, Egyptian Arabic nouns also lose the category of case, as compared to MSA, which confirms such a tendency in dialects. Plural forms are made by adding a suffix at the end of a noun, but sometimes it is achieved through a change in the vowel structure of a word. The grammatical influence of French is observed in Egyptian Arabic in the form of a double negation formed by the particles ma- and s- (“Arabic (Egyptian Spoken),” n.d.) Several common phrases, which can be used in Egyptian Arabic, are listed in Table 4. Unlike MSA, the Egyptian dialect is open to borrowings from other languages, and this tendency has been observed throughout its existence. There are many vocabulary borrowings from Coptic, which was Egypt’s dominant language prior to the arrival of Arabic. Simultaneously, French, Italian, and Greek serve as the primary sources of contemporary neologisms, but the vast majority of them come from English.

Table 4. Egyptian Vocabulary as Compared to MSA.

Analysis of the Arabic Language Varieties

As mentioned above, the phenomenon of diglossia is particularly important in the Arabicphone world. In a way, its varieties can be described as a “high” form, or written formal MSA, and a “low” one, or vernacular dialects, which are spoken but not written. Accordingly, researchers often deem the two varieties as practically separate languages, and MSA is given the leading role as the “correct” version of Arabic. This tendency is particularly strong in education, but Al-Batal (2017) argues that such an approach is unjustified and even detrimental to the students’ command of the language. Writing and speaking are two ultimate forms of mastering a language, and neither aspect can be neglected, as it would leave the learner partially illiterate. According to Al-Batal (2017), different forms of Arabic must be considered two sides of one notion instead of being viewed as inherently different disciplines. Indeed, if the studies focus on MSA, students will not be able to engage in an actual conversation since this variety is not used verbally.

Nevertheless, the importance of MSA is not to be diminished since this form of Arabic derives directly from the language of the Qur’an. It preserves its status as the official language of Arabic-speaking countries, and all formal international communication uses MSA as a universal instrument. Therefore, it accounts for another indispensable aspect of the Arabic language command. While it appears easier to focus all efforts on one of the varieties, both MSA and colloquial dialects cannot exist separately. In this case, difficulties faced by Arabic learners should be deemed as necessary challenges taken with dignity. As MSA’s role of pivotal importance in the modern environment is confirmed, it is possible to draw a similar conclusion regarding Classical Arabic. Research presented in this paper demonstrates that CA is not an archaic form replaced by MSA. On the contrary, MSA appears to be the result of a natural evolution of CA, as the two forms share the majority of grammar, syntax, phonetics, and vocabulary.

Summary and Conclusion

In conclusion, the Arabic language receives increased attention from researchers due to its complexity and diversity of forms. Historically, Classical Arabic became the first well-documented variety of the language, as it was used in Qur’an, thus obtaining a sacred status. As the Muslim community began its transition toward secularization in the 19th-20th centuries, a necessity of language reformation arose, as well. Modern Standard Arabic became a logical descendent of the classical forms, aiming at meeting contemporary needs. It is now used in formal and written forms, serving as a lingua franca of Arab nations. Simultaneously, local dialects are used exclusively for informal, verbal communication. While the two forms have an array of differences, it is unwise to consider them separate entities. MSA and dialect forms coexist in the modern environment, and both of them are equally important. Accordingly, since MSA is a derivative of CA’s evolution, sharing the majority of aspects with the latter, it is possible to state that the classical form of Arabic remains an important communication mode.

References

Al Neel, H. A. (2019). The origins of the Arabic language.

Al Suwaiyan, L. A. (2018). Diglossia in the Arabic language. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 5(3), 228–238.

Al-Batal, M. (2017). Arabic as one language: Integrating dialect in the Arabic language curriculum. Georgetown, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Arabic (Egyptian Spoken). (n.d.).

Arabic (Moroccan Spoken). (n.d.).

Kamusella, T. (2017). The Arabic language: A Latin of modernity? Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics, 11(2).

Testen, D. (n.d.). Semitic languages.