The term “catalog” is quite well known and well spread all over the world. It is frequently used in various fields such as science, economics, sales, manufacturing, food industry, beauty sphere, culture, and art. The word “catalog” comes from the Greek language. Its meaning refers to the categorization and sorting of some items or notions according to certain criteria and features they possess (Strout, n. d.).

This is the best and most rational way of organizing and structuring various spheres of knowledge and setting order within them. This paper explores the styles and types of street art, graffiti namely, their main features, their kinds, shapes, fonts, and sizes because this kind of art is often overlooked and frowned upon. Street art started to be viewed as a kind of art only several decades ago. Street art professionals, artists, and experts today study this field to reveal its hidden meanings and symbols.

Street art is popular all over the world; it can often be seen in urban areas. In this paper, I intend to reveal the complexity of street art and its connection to typography to show that this subject is worth studying. Street artworks possess several typographic features according to which they can be classified and identified.

Street art is observed and encountered mainly in urban areas that have large buildings and tall walls. In Great Britain, at least eighty five percent of population dwells in the urban areas. The public perception of the urban landscapes is mainly negative, and street art and its perception by the masses adds to the overall dissatisfactory idea about is a phenomenon and the influences it produces (Conway, 1999).

Understanding of street art is complicated by the absence of the information necessary for its categorization. Just like in languages and translation, understanding graffiti styles required proper references to the authors’ intentions (Moi, 2010). Distinguishing the message of the works and their meanings is highly important to avoid misinterpretation (Hooks, 2013).

To study street art better, the object based learning is applied, the learning is based on the specimens and examples of various works, their comparison, and understanding, object-based learning provides the learners with reliable evidence and materials for conclusion drawing (Introduction to object-based learning, 2014). Street art includes various kinds of writings; it has a lot to do typography, which is the art of lettering and fonts.

Over the last several decades, the public perception and attitude towards art and design changed, as a result, many new modern streams of art occurred (Disobedient Objects: About the Exhibition, 2014). It is a well-known fact that today modern street art is established as the subject of municipal legislation that has a goal to protect and preserve the urban aesthetics and property values (Mettler, 2012).

According to the attitudes towards this kind of art, the society is now divided into the individuals that are against it and consider it as visual pollution of urban areas and the ones that support this art and find it unconventional and interesting (Novak, 2014). The complexity of lettering and typography and exclusivity of these writings is often overlooked.

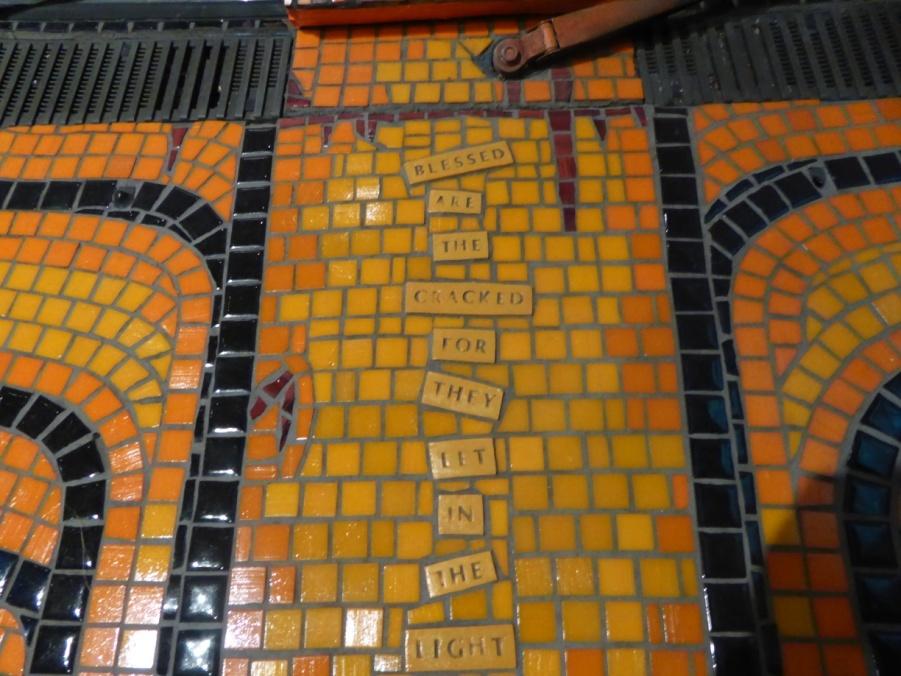

A work from “Disobedient Objects Exhibition” In Victoria and Albert Museum.

A work from “Disobedient Objects Exhibition” In Victoria and Albert Museum.

A Tube station nearby Greenwich (industrial area).

The term “graffiti” is used to refer to all kinds of writings on various surfaces. The writings are divided into common ones and community-based ones (Phillips, 1999). Common ones include the notes left by children and non-professionals their typography is very basic. Community-based kind of graffiti is called this way because these writings and paintings are designed to eliminate the masses from understanding their meanings; typography of these writings can be extremely complex.

The experts distinguish between various genres of street art, its cultural messages, and subvertising; the street art professionals also explore various jargons and specific terms in street art (Waclawek, 2011). The experts agree that there are different perspectives on the aesthetics and the representations of beauty, talent, and professionalism, yet there are still debates concerning the question whether or not street art and graffiti should be considered as artworks, but they are typographical works (Freud, n. d.).

The main purpose of this kind of art is self-expression. Street artists work on their typographic techniques and skills constantly learning and improving (Graffiti, 2014). Graffiti and its typography can also be viewed as a form of communication between the insider communities. Today, graffiti is studied by various scientists such as psychologists, anthropologists, historians, and various artists as a way of understanding political, social and cultural relationships within a certain community (Bartolomeo, 2001).

The first signs of street art and graffiti started to appear in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s (Aziz, 2011). Groups of young people armed with spray paint cans were gathering in the streets spreading various writings all around the city. They perfected their works and skills practicing typography on paper first, showing their creations to each other, learning and improving (StyleWars1982, 2011).

Graffiti and street art boom is mainly viewed as a massive fashion for vandalism. Not many people take into consideration the political and social aspects of this movement. The beginning of street art practice is synchronized with the end of the Vietnam War and the years of Reagan’s rule (Lynch, 2012). The researchers that look deep into the origins of the street are today value its works because they are the examples of the political statement from the youth.

Style wars of the 70s resulted in the massive confrontation of graffiti and street art from the side of the city authorities at the beginning of 1980s, works were eliminated, trains with signatures were removed (History of Street Art, n. d.). Today, society starts to notice the beauty of street art, its typography, and styles.

Chronologically, the roots of the phenomenon of street art can be traced back to the Stone Age when our forefather first started to engrave their sketches in the caves (Pyke, 2013). Actually, this happening may be considered as the very beginning of the development of art in general, as humans first started to use tools to produce expressive works (Benjamin, 1998).

The terminology in graffiti and street art includes such notions as “Tag”, which is a signature of an artist, the artists design their pseudonyms and spread them around the city, tags are painted with spray paint or written with markers, their typography is very basic (Chaudhury, 2013).

“Bombing” means painting quickly on windows or walls of the train cars (Kinds and Styles of Graffiti, 2014). The styles of graffiti typography and fonts are multiple among them there are a bubble, 3D, wild style, stickers, stencil, brush and realistic (Style, 2011).

Street art and graffiti are based on a variety of fonts and shapes they employ to carry out their messages. Standard typographic fonts are used for motivational messages or subvertisement, these writings have to be clear for any kind of reader. This is why the examples from the Victoria and Albert Museum have clear and correct shapes and undisguised meaning. Font size is very important for such writings – they have to be accessible and easy to read and comprehend.

Street art competitions and masterpieces are based on the inclusion of very artistic fonts invented by the authors. They can be combinations of already existing models or a new style. Colouring of the fonts is very important in typography. The same letter colored in different ways can be read differently, which will cause misunderstanding. For example, wild style writings can be particularly hard to read for an unprepared viewer.

Lighter colors tend to visually expand the outlines of the letters and confuse the reader, besides, additional curves, strokes, and lines present in artistic fonts with distorted shapes make some words particularly unreadable (Curtis, n. d.). The use of outlines can help make the font visually obtain 3D, or X-ray, or glowing effect. They are also needed in fonts with negative spacing and overlapping letters to create borders.

Bubble-shaped font that is rather popular in street art typography is an example of confusing writing where C can look like G, H can resemble A, and O and D look especially similar. In street art such as graffiti, typography is more important than the meaning of the writing, the artists compete delivering interesting new shapes and developing unconventional looks for standard letters. Lines, shapes, coloring work together to add new alphabets to the list of fonts street art masters work with.

The contemporary street art experts distinguish between fourteen main street art styles. Initially, thirty different styles were identified, but gradually their number was reduced to fourteen due to the introduction of new criteria (Gottlieb, 2008). According to this system of identification of street artworks, the style of every piece can be determined with the help of a special questionnaire that follows various features of the artwork.

For example, the works are identified according to the number of colors used, the size of the letters, the outlines, and edges of the letters, spacing, and letter overlapping (Sils, 2009). Each of the criteria for the evaluation of artworks has a code letter and several numbers meaning the degree to which certain criteria are observed in the work. As a result, every work can be coded and identified according to its features.

This system of street art evaluation was invented by its supporters. At the same time, there is another set of criteria for graffiti and street art developed by the legal authorities. This system evaluates the harm caused by the work to private properties and city landscapes.

In conclusion, street art and graffiti have several systems of evaluation most of which are based on typography rules and designs. Each of the sets of the criteria for the evaluation of the street artworks was designed out of necessity to either understand the meaning of the art or to prevent the acts of vandalism.

Both the supporters of this kind of art and its opposition felt the need to study this art from various points of view in order to develop a better understanding of its authors and their ways of thinking. Street art today gets widely re-appreciated and re-evaluated. Its streams and styles become more advanced and professional.

Some of the masterpieces are very impressive. The number of haters of street art becomes less as it develops a sophisticated side and obtains informative and entertaining functions. The deeper this art becomes, the more new systems of its cataloging and researching will emerge.

Reference List

Aziz, P. 2013. Timeline of Graffiti and Street Art Influences. Web.

Bartolomeo, B. J. 2011, Cement or Canvas: Aerosol Art & The Changing Face of Graffiti in the 21st Century. Web.

Benjamin, W. 1998. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Web.

Chaudhury, N., 2013, Graffiti styles: Five types of street art and artists to look for. Web.

Conway, H. 1999. Design History: A Student’s Handbook.

Curtis, C. n. d. Graffiti Archeology. Web.

Disobedient Objects: About the Exhibition, 2014. VAM. Web.

Gottlieb, L. 2008, Graffiti Art Styles: A Classification System and Theoretical Analysis. Jefferson, McFarland.

Graffiti, 2014. Art Republic. Web.

Freud, Z. 1919. The “Uncanny”.

History of Street Art, n. d. Time Toast. Web.

Hooks, B. 2013, Dig Deep: Beyond Lean In. Web.

Introduction to object based learning, n. d., UCL. Web.

Kinds and Styles of Graffiti, 2014, Calligraphy. Web.

Lynch, S., 2012, Coloring Outside the Lines: The History of American Graffiti.Web.

Mettler, M. L. 2012. ‘A First Amendment Argument for Protecting Uncommissioned Art on Private Property’, Michgan Law Review, vol 111, no. 2.

Moi, T. 2010, ‘The Adultress Wife’, London Review Of Books, vol. 32., no. 3., pp. 3-6.

Novak, D. 2014, ‘Methodology for the Measurement of Graffiti Art Works: Focus on the Piece’, World Applied Sciences Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 40-46.

Sils, P. 2009, Cataloging Street Art. Web.

Strout, R. F. n. d. The Development of Catalog and Cataloging Codes.

Style, 2011, FatCap. Web.

StyleWars1982, 2011, Style Wars Hip Hop Documentary. Web.

Phillips, S. A. 1999, Wallbangin’: Graffiti and Gangs in L.A. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Pyke, S. 2013, History of Graffiti; Street Art Timeline. Web.

Waclawek, A. 2011, Graffiti and Street Art. Web.