Introduction

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, often referred to simply as the Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or the DRC, and previously known as Zaire, is one of the largest countries in Africa in terms of both population and land area. Since gaining independence in 1960, the country has remained politically unstable (Nugent, 2021). The assassination of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba and the subsequent weak leadership of President Joseph Kasavubu led to a military coup by Joseph Mobutu in 1965. The dictator could not control the country, and various rebel groups emerged in different parts of Congo.

The political instability in the Congo was worsened in 1994 following the genocide in Rwanda. The Hutu militia fled to northern Congo when a Tutsi took the government. The militia from Rwanda joined forces with rebels in Northern Congo (Nugent, 2021). The problem in the Congo has also persisted due to illegal mining and gold trade. Most refugees displaced by these fights have migrated to different parts of the world, including the United States.

The United States has remained one of the preferred destinations for refugees and immigrants worldwide. As Haines et al. (2017) observed, refugees are often forced to do so, unlike immigrants who are fully prepared and willing to leave their home country for another. The majority are often ill-prepared to live in a foreign land and would rely on support from the host government or the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to get the basic needs. They face numerous challenges, from the language barrier to cultural differences.

In the United States, there is a constant effort to integrate and assimilate these foreigners, enabling them to succeed in their new country (Bose, 2018). Studies have shown that most refugees settle in the United States even after their country achieves political stability (Davila, 2021). As such, it is necessary to find ways of supporting them to become self-supporting in the country. Enabling them to acquire the education and training necessary for the job market is the most effective way to assist these refugees.

In this chapter, I look at the challenges these refugees face as they transition into the United States’ higher education system. The chapter examines their participation in athletics, English proficiency, family-school relationships, and the status of Congolese refugee students. The chapter discusses the transition to post-secondary education, the challenges and barriers it presents, and the role of various stakeholders. The chapter then examines how schools prepare students for higher education and careers, and the role of community support and collaboration with various stakeholders. The detailed literature review will enable the identification of gaps that need to be addressed by collecting and analyzing primary data from a sample of participants.

Athletics

Sports are among the best ways of integrating foreigners into the local population. Congolese students attending schools in the United States must interact with locals within that region. Sports create a common interest that transcends language and cultural barriers (Fazel, 2018). Soccer, football, and basketball are among the most popular sports in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Through these games, they interact with the locals and find a common purpose in the host communities. Dikembe Mutombo, Christian Eyenga, Bismack Biyombo, and Emmanuel Mudiay are some Congolese-born athletes who have achieved immense success in basketball in the United States (Torres, 2018). Their talent in this sport achieved national recognition and acceptance in the host country.

In the United States, many schools and colleges often sponsor learners who demonstrate unique skills in specific sports. Sports are considered among the best alternatives due to the language barrier and other challenges that may impact refugees’ academic success (Onchwari & Keengwe, 2019). A learner can focus on any field, and if they are successful, they will be guaranteed scholarships in some of the best colleges in the country (Davila, 2018). They can further their education while utilizing their talent as a career; they can pursue both during and after college. The Congolese athletes mentioned above identified their talents while in college, and through the support that they received from family, the community, and the schools they attended, they became successful.

Athletics is one of the most unifying factors in a highly diversified community. Refugees in the United States can utilize sports to learn about the new culture and integrate into their new communities (Cureton, 2020). During major tournaments, people ignore racial, religious, or other demographic differences. They work together as a community, whether as players or supporters of a particular team.

These events create a platform that enables refugees and hosts to realize their common interests. It promotes tolerance, as there is a desire among all stakeholders to assist one another and facilitate communal success (Davila, 2021). The success will be attributed to the team, not to any individual.

In many cases, refugees would stay in camps before they can be integrated into society. The problem is that they can remain secluded from the rest of the community for an extended period. Most of them do not understand their position in the new country, and even if they are offered some form of education in these camps, they still feel that they are not part of the host community (Mahoney et al., 2020).

Athletics offers them the best opportunity to interact with the local community even before integration. They do not necessarily have to understand the hosts’ language to play soccer, football, basketball, or athletics. The rules are universally familiar, and the language barrier does not limit meaningful competition.

Some of the misinformation and misconceptions about hosts or refugees can be addressed through such interactions (Chahine, 2020). A unique opportunity is created for the hosts to learn more about the refugees, and for the visitors to gain a deeper understanding of the host community. As such, the government, leaders in the host communities, and other relevant stakeholders should encourage sporting activities among the Congolese refugees.

English Proficiency

The Democratic Republic of Congo, just like many African countries, has numerous indigenous languages. French, Kikongo, Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba are some of the widely spoken languages in the country (Nugent, 2021). A slight minority of the Congolese, especially those who attend international schools, can communicate fluently in English. The vast majority of the population, especially people with low incomes who live in the rural parts of the country, are often the worst affected by militia activities. They form the largest number of refugees coming to the United States (Bose, 2018). This means they can barely communicate in English, the most common language in the United States.

One factor defining one’s academic success in the United States is proficiency in English. According to Cureton (2020), some private international schools in the country teach using foreign languages such as French, Spanish, and German, among others (Wearne, 2021). English remains the standard language for instruction in almost all public schools in the country (Wearne, 2021).

Refugees from Congo are expected to learn English because it is the only national language in the country (Bayoh, 2016). The primary challenge that most Congolese refugees face is that they are not proficient in the English language. They must spend a considerable time learning the new language before they can attend regular classes in the country.

The recently introduced Common Core State Standards (CCSS) pose even a greater challenge to these foreign learners. The new standard has set a higher bar for high school students, especially in English and mathematics, to qualify for specific college courses (Inks, 2021). It also encourages parental involvement in the learning process. The problem is that most of these refugees do not understand English. Congolese parents often struggle to assist their children with their assignments in the United States due to various reasons, including the language barrier.

Young learners just starting their education in the United States may quickly adapt to the new challenges. They can easily learn and become proficient in the English language. Older students on the verge of entering college may struggle with the language (Brown & Bousalis, 2017). At such advanced levels of education, it is not easy to learn a new language, which must be used as the standard mode of issuing instructions in all the other subjects. Their performance will drop in languages and other subjects taught and examined using the new language.

Family-School Relationships

Parental involvement in the learning process for their children has increasingly become important with the introduction of the CCSS in the country, according to Haines et al. (2021). When parents are actively involved in their children’s education, they will better understand the role they need to play. Regular teacher-parent engagement makes it easy for a parent to understand their children’s progress. They will know specific weaknesses that should be addressed and strengths that can help define their career paths (Mendenhall, Bartlett, & Ghaffar-Kucher, 2016). Parents will also appreciate the need to purchase specific learning materials for their children during regular engagement.

Refugee families in the United States are expected to participate actively in their children’s learning. Family involvement with school activities is a socio-cultural issue one learns in a society (Bayoh, 2016). In some parts of the world, especially in most developing nations, parents expect teachers to be fully responsible for their children’s academic and social growth.

Once a child is released to go to school, a parent is not expected to be actively involved in the learning process beyond paying school fees and other necessary expenses. When they come to a new country with a new cultural practice, they may take time to adapt (Hos, 2020). They may find it out of the norm when they are required to maintain a close relationship with the school.

These families will need assistance from the local schools where their children learn. The majority of the Congolese refugees face numerous challenges in the country. There is the language barrier, culture shock, lack of steady income, and inability to work unless they get the relevant documentation (Dryden-Peterson, Adelman, Bellino, & Chopra, 2019). Some of these challenges can be addressed if the family maintains a family-school relationship.

The school offers a perfect opportunity for the parents and other family members to interact with the local community. The constant interaction makes it easy for the refugees to learn the new language. They also get the opportunity to learn the local culture and practices. It eliminates misconceptions and stereotypical information that the locals may have towards the foreigners (Wilkinson & Langat, 2012). It is the best way of acculturating the refugees into the local community, especially if it becomes evident that they are less likely to go back to their home country.

Congolese Refugee Students’ Status

The United States remains one of the preferred destinations for Congolese refugees. According to Nyamnjoh et al. (2021), because of the consistent immigration of these refugees over the years, the United States currently has a population of over 10,000 Congolese refugees settled in different parts of the country. Most of them are settled in New York, Boston, and Washington.

A significant proportion of this population is students. Although the official status of these students remains that of a refugee, there has been an effort to integrate them into the local communities. The majority are often unwilling to return to their home country even when assured of political stability (McNeely et al., 2017). Going through the local education system makes it easy for them to be integrated into these communities.

Transition to Post-Secondary Education

Congolese refugees who get an opportunity to go to school in the United States finally have to transition to post-secondary education. These international students must meet the Grade Point Average (GPA) requirements, as do other students across the country, to be admitted into these institutions of higher learning. Wachter (2016) notes that they must also be subjected to numerous English language tests and other examinations before transitioning to these institutions.

Some of the tests they have to pass include the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), International English Language Testing System (IELTS), and Pearson Test of English (PTE) (Oliveri & Wendler, 2020). The tests create extra hurdles for these foreign learners interested in furthering their education. Some opt not to pursue post-secondary education after several failed attempts at these exams. Those who manage to pass still have to face numerous other challenges, which will be discussed further in subsequent sections of this chapter.

Challenges and Barriers Faced by Refugee Students

The Congo remains one of the most politically unstable countries in Africa despite the massive effort by the international community to help address the problem (Inks, 2021). The activities of militia groups in many rural parts of the country, especially the Northern Province, have left many people homeless (Mahoney et al., 2020). Although most refugees are forced to flee to neighboring countries of Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania, they prefer traveling to Western countries such as France, the United Kingdom, and the United States for permanent residency away from home (Haines et al., 2015).

As the problem persists in their home country, they must consider permanently relocating to these foreign countries for their safety and economic prosperity. However, it is essential to note that these refugees face numerous challenges once they migrate to the United States. The following are some of the significant issues that the refugees have to deal with in the United States.

Growing Cases of Xenophobia

The United States has remained the most preferred destination for immigrants and refugees (Joycea & Liamputtong, 2017). Most of them come to the US because of the American dream, the desire to achieve the socio-economic success that the country promises. However, there has been an emerging problem in recent years.

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attack that claimed more than 3000 lives and left many people with varying degrees of injuries created massive awareness about the dangers of terror attacks (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2020). Investigations revealed that the attacks were planned by Al Qaeda, with assistance from some of the local immigrants. It became evident to the American populace that some of those who come to the country have ill intentions against the United States.

The San Bernardino attack of 2015, the Orlando nightclub shooting of 2016, and the Naval Air Station Pensacola shooting are some of the recent major terror attacks in the United States. Several people lost their lives in these attacks, and several others were wounded. Investigations revealed that in all three cases cited above, the perpetrators were either immigrant or their parents were immigrants (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2020).

Society was quick to develop a pattern, associating immigrants with terrorism. It created xenophobic tendencies that had not existed before. The locals felt that there was an inherent danger to their lives and properties when there were foreigners in their communities.

In the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo, there is a significant problem of terrorism that the government and the international community are fighting. However, religion-based terror, which is the main threat that the US is facing in its fight against terrorism, is rare (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2020). It is less likely for a Congolese immigrant to be recruited into and to participate in acts of terror.

The fact that an overwhelming majority of the population (over 95%) are Christians makes it less likely for them to be recruited in religious wars against the United States (Joycea & Liamputtong, 2017). However, the perception of the locals towards immigrants also affects these Congolese refugees. They are viewed as a potential threat to the locals.

Xenophobia significantly affects acculturation and integration efforts geared towards the absorption of the refugees into local societies. They are denied the social support they need to adapt to the new environment (Joycea & Liamputtong, 2017). There is a constant feeling among the locals that refugees should be confined within specific camps until they can be repatriated to their home countries.

Some locals express their displeasure towards the foreigners in social gatherings, at home, and even in learning institutions. It has worsened the problem because the children of the refugees attending local schools are not spared from such attacks. Their peers view them as children of terrorists or future terrorists who do not mean well for the country (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2020). Instead of getting the support they need from their peers to master the English language and other subjects, they are verbally and sometimes physically attacked. The school experience becomes significantly frustrating as they develop a fear of going to school because of the attacks.

Fighting xenophobia has proven to be a significant challenge in the United States, especially after the September 11, 2001, Al Qaeda attacks. Some of those propagating xenophobic ideas are the political leaders. During the electioneering periods, they look for rhetoric that can easily elicit the masses’ emotions.

The impact of the attack, and many others that have occurred since then, is an emotional scar that can easily be scratched by politicians keen on ascending to power (Brown, 2021). Those who are worst affected are the immigrants, especially the refugees who were forced to come to the country because of events in their home country. When Congolese students are forced to spend most of their time in the refugee camps, they lose the opportunity to interact with their peers and gain a better understanding of the English language. They are denied the opportunity to learn the local culture and interact with those who can help define their future in the United States or anywhere else.

Socio-Economic Factor

Socio-economic forces may also significantly negatively impact refugee students in the United States (Joycea & Liamputtong, 2017). The language barrier is just one of the numerous problems these students face. There is also the problem of limited resources. According to Wachter (2016), immigrants come to the United States after a careful plan. Some have relatives or loved ones in the country who can offer them the assistance they may need.

The same is not true with the refugees who are forced out of their country because of various reasons. In many cases, they have few possessions that they could salvage when disaster struck. They wholly rely on the UNHCR, the host government, and other international organizations to support them in meeting basic needs (Wabia, 2020).

The lack of economic empowerment means they must pay for their academic needs in the country. They must attend schools that are paid for by the relevant agencies sponsoring their stay in the country. Sometimes they must be taught within the refugee centers in settings where they do not interact with locals.

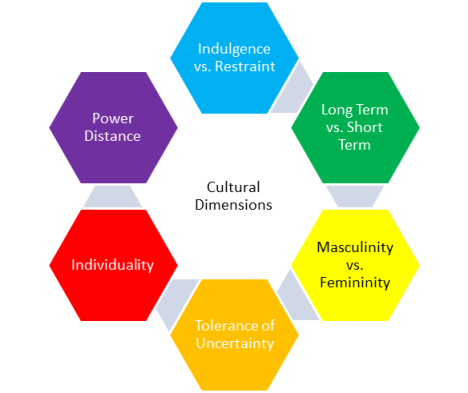

The social structure of families and communities in Africa significantly differs from that in the United States. According to Wabia (2020), there is a communal approach to solving social problems in many African countries. On the other hand, the United States is more individualistic, as shown in the cultural dimension theory shown in Figure 1 below. In Congo, it would be common for community members to assist with the unique challenges affecting these refugees. However, that is not the case in this country, where everyone is expected to address their issues.

Masculinity versus femininity is another culture shock that refugee students may face in the United States. In Congo, especially regions controlled by rebels, where most of these refugees come from, the people highly value boys over girls. Boys are expected to attend school, if possible, and acquire knowledge to help them earn a living for their families (Nugent, 2021). They are also expected to train as militia to defend their communities in case of attacks.

On the other hand, girls are primarily expected to stay at home and take care of domestic chores. In the US, women are just as liberated as men, which is uncommon in Congo. Female refugee students may take time to embrace the new culture that seeks to empower them. The younger students can easily embrace the new system in the country. However, older learners who have already embraced the traditional African culture and practice may struggle with the new system.

Power distance is a socio-cultural issue that may also affect refugee students’ ability to succeed academically. There is low power distance in the United States, which means that subordinates can directly engage their leaders and even challenge them when they feel it is necessary (Berger, 2021). In Africa, especially in places ruled by the rebels, one cannot challenge their leaders in any way. Any form of disobedience can be punishable by death as these rulers rely on fear and absolute loyalty to govern their subjects (Tapscott, 2021).

The students have already been trained to avoid challenging those in positions of power. As such, they become inactive learners who expect the teacher to issue instructions to facilitate the learning process. The problem is that CCSS is a student-centered curriculum where learners must take leading roles in learning (Stillman, Anderson, Beltramo, & Gomez-Najarro, 2017). It is a significant shift from the teacher-centered system, where learners are significantly inactive in the learning process. It may take some time before these international students can embrace the new system where they actively participate in the learning process.

Tolerance of uncertainty is another concern that may harm refugee students in the country. Surowiec and Manor (2021) explain that Americans are highly tolerant of uncertainties. After the American Civil War, the country has enjoyed decades of peace. The government has remained committed to protecting its citizens from external aggression.

At the same time, economic systems have been working well, assuring citizens that they can easily get another job even if they lose their jobs. The same is not true in some parts of Africa, especially in the Congo, where the future is highly uncertain. There is a constant fear of an attack by government forces or rival rebel groups. These children have witnessed their parents, relatives, and friends lose their lives in such attacks.

There is also instability on the economic front, mainly because of limited employment opportunities (Nugent, 2021). These students lack the mental freedom that is needed for them to focus on their education for a better tomorrow. They constantly worry about current events and how they may affect their lives.

Psychological Factor

A student can only achieve academic success if they are psychologically settled. Bayoh (2016) explains that one of the significant problems that refugees have to manage is mental distress. Immigrants from the Congo are forced out of their homes because of the constant wars in these regions. Some have lost their loved ones, while others sustained significant injuries.

Having to witness the brutal mass murder of their family members, friends, and families back home before escaping or being rescued has left many of them battling posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Some of them have received therapy to help them overcome the memory of these traumatic experiences, while others have not. The nightmare that they have to deal with in this new country in terms of mental distress significantly affects their academics(Ghatol, 2019).

When they face xenophobic attacks in the new country, their fear is worsened. They feel that at any moment, they can still be attacked by these foreigners, just like it was the case back home (Torres, 2018). They spend most of their time worrying about their security and future instead of concentrating on classwork. The situation can become worse if their PTSD is not effectively addressed (Ghatol, 2019). Such a student can easily become aggressive because of the desire to protect themselves from a perceived threat. In such a case, teachers will develop a fear of handling such students because of their erratic and unpredictable behavior. They become unwanted visitors who cannot effectively fit into the country’s education system.

Educational Factor

Refugee students in the United States also face educational challenges that need to be addressed. K–12 has been the standard education system in the United States for decades. CCSS was only meant to address the identified gaps in this education system (Stillman et al., 2017). Congo has an entirely different education system from that of the United States. The problem arises when a Congolese student has to be admitted to an American school. One of the tests they must pass to be admitted to public schools is an English exam (Stillman et al., 2017).

The problem is that most of them do not even understand the language. The few that do cannot be admitted into equivalent classes in the country because of the different education systems (Oliveri & Wendler, 2020). This has remained a challenge for these refugees keen on continuing their education in the country.

They are forced to spend an extra year learning English, which may not effectively equip them with the skills they need to succeed in the local education system (Stillman et al., 2017). Most of them cannot afford to attend private international schools where French is the standard mode of issuing instructions because of the cost and the fact that such institutions are less common. These challenges often reflect their dismal performance as they have to sit for the same exams as other students across the country (Stillman et al., 2017).

Institutional Factor

Refugee students’ challenges in the United States can be attributed to weak institutions (Wachter, 2016). The United States shares a land border with only two countries, Canada and Mexico. Canada is a relatively stable nation with a stable economy, while Mexico has remained relatively stable despite security challenges associated with drug lords.

The main problem that the country has been dealing with for decades is illegal immigration, especially from Mexico, Central, and South American countries (Brown, 2021). Systems and institutions have been developed to help address this problem. However, the country has weak institutions to help deal with the challenges of refugees. The institutional weakness has significantly impacted refugee learners in the country, especially those who cannot communicate fluently in English.

Language Factor

Language remains a significant barrier to refugee students in the United States. A significant number of these international students cannot communicate fluently in English. Those from Congo may not even have the basic knowledge of the language (Inks, 2021).

Attending local schools where English is the standard mode of communication becomes a significant challenge. They must spend some years learning the language before resuming classes. Most refugees can only speak Lingala, Kikongo, or other indigenous African languages(Rotberg, 2020). Helping such individuals, especially if they are advanced in age, becomes a significant challenge. It is common for such individuals to opt for manual jobs instead of going to school.

Role Construction of Families, Students, and Teachers

The construction of families, students, and teachers is essential in ensuring a successful transition of Congolese students to post-secondary education. As discussed above, these students are expected to take numerous exams before they can be allowed to join institutions of higher learning. Most of these exams are meant to test their mastery of the English language (Cureton, 2020).

The problem is that their main challenge is the language itself. Families, teachers, and students need to work as a unit to help the students overcome these challenges. A close interaction between local teachers and families of these refugees can help identify specific challenges that students face and how they can be addressed(Mendenhall et al., 2016). Teachers can help parents find a common way of solving the problem. Parents and teachers should clearly understand the role that they need to play in helping these learners to overcome the challenges that they face.

Role of School in Preparing Students for Post-Secondary Education and Career

Schools across the United States have a role to play in ensuring that Congolese students are adequately prepared for post-secondary education and careers in this country. The discussion above shows that these learners face numerous challenges as they strive to achieve academic success. Language barrier and culture shock have been identified as significant concerns for these students (Brown & Bousalis, 2017).

Schools should develop ways of assisting these students in overcoming the barriers. Besides the standard classes and subjects, schools can develop extra units that address their challenges. One unit should focus on enhancing skills and competence in the English language. It will enable the learners to excel in other subjects and pass the English tests that local universities require before one can be admitted.

The second unit can focus on acculturation for these international students (Oliveri & Wendler, 2020). They should be assisted in understanding the American culture and how they can easily fit into it. Schools should prepare these students so that they can understand what to expect when they go to college. They may also need assistance in choosing appropriate career paths once they are in institutions of higher learning based on their unique strengths and weaknesses (Oliveri & Wendler, 2020).

Community Supports and Collaboration with Schools, Teachers, Families, and Students

The local community in the United States has a significant role in assisting refugee students to succeed academically, especially when they ascend to institutions of higher learning (McNeely et al., 2017). One of the ways through which such support can be granted is by collaborating with the local schools to organize tournaments that bring together the locals and foreigners. Basketball is one of the most popular sports in both countries (Torres, 2018).

These sporting events can help identify and nurture talents among refugees. As they transition to college, they will be aware of their unique talents and how they can use them to achieve success in college. They can even consider pursuing a career in these sporting activities (Oliveri & Wendler, 2020). As discussed in the section above of this chapter, various Congolese nationals have had successful careers in basketball in the United States. Through such sporting activities, the refugee students can learn the local culture and how they can embrace it.

Xenophobia was identified as a significant concern that limits the ability of refugee students to be successful. The local community can help battle this problem to enhance the quality of life for these foreigners. Through regular engagements with the refugees, the local community will understand their values and cultural practices.

The engagement will make it possible to eliminate some of the misconceptions and misinformation about the Congolese refugees. Accepting foreigners is essential in fostering closely-knit communities. The refugees will find it easy to ask for help when they need it (Davila, 2021). The local community can work closely with schools, teachers, and families to organize music festivals. Congolese are known for their music across Africa and Europe. They can use their talent in music to define a career path in the United States.

Gap in the Literature

When conducting a literature review, it is essential to identify gaps in the existing body of knowledge. Evidently, there is limited knowledge about Congolese refugee students’ challenges, specifically when transitioning to post-secondary education. Although literature exists about challenges immigrants face, how this subset of immigrants is affected remains unclear.

It is important to note that refugees from different parts of the world face varying challenges in the United States because of their socio-economic and political backgrounds. The study was narrowed down to specific challenges they face when transitioning to higher learning institutions. It is also important to note that the challenges refugees from Congo faced in 2000 differ from those in 2020. Terror activities, economic challenges, and geopolitical concerns of the United States have transformed the perception that the local community has towards refugees. Collecting primary data from Congolese refugees is necessary to understand the current concerns and challenges the students face as they transition to post-primary education.

Conclusion

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is still plagued by political instability as militia still controls part of this African country. Refugees from this country are often hosted by neighboring countries temporarily before they travel to Western countries. In the United States, refugee students face significant challenges. There is a language barrier, culture shock, and emerging xenophobia that they have to battle as they seek to advance their education. When transitioning to post-secondary education, these students need the support of the teachers, parents, friends, and community to overcome these challenges and achieve academic success.

References

Bayoh, D. M. (2016). What are the barriers to economic self-sufficiency of Congolese refugees in Abilene, Texas? (Publication No. 5-2016) [Master’s thesis, Abilrne Catholic University]. Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

Berger, A. (2021). Luxury and American consumer culture: A socio-semiotic analysis. Cambridge Scholars Publisher.

Bose, P. (2018). Welcome and hope, fear, and loathing: The politics of refugee resettlement in Vermont. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 24(3), 320-329.

Brown, D. (2021). In the shadow of the fallen towers: The seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, and years after the 9/11 attacks. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Brown, S. L. & Bousalis, R. (2017). Empowering young minds through communication, creative expression, and human rights in refugee art. Art Education, 70(4), 48-50.

Chahine, C. (2020). Towards African humanicity: Re-mythogolising Ubuntu through reflections on the ethnomathematics of African cultures. Critical Studies in Teachoing and Learning, 8(2), 96-108.

Cureton, A. (2020). Strangers in the school: Facilitators and barriers regarding refugee parental involvement. The Urban Review, 52(1), 924-949.

Davila, L. T. (2018): Multilingualism and identity: articulating ‘African-ness’ in an American high school. Race Ethnicity and Education, 3(1), 1-14.

Davila, L. T. (2021). Newcomer refugee and immigrant youth negotiate transnational civic learning and participation in school. British Educational Research Journal, 2(1), 1-17.

Dryden-Peterson, S., Adelman, E., Bellino, M., & Chopra, V. (2019). The purposes of refugee education: Policy and practice of including refugees in national education systems. Sociology of Education, 92(4), 346-366.

Fazel, M. (2018). Psychological and psychosocial interventions for refugee children resettled in high-income countries. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(1), 117-123.

Ghatol, D. (2019). Academic stress among school students. Allied Publishers.

Haines, S., Reyes, C., Ghising, H., Alamatouri, A., Hurwitz, R., & Haji, M. (2021). Family-professional partnerships between resettled refugee families and their children’s teachers: Exploring multiple perspectives. Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 499(1), 1-13.

Haines, S., Summers, J., Palmer, B., Stroup-Rentier, V. L., & Chu, S. (2017). Immigrant families’ perceptions of fostering their preschoolers’ foundational skills for self-determination. Inclusion, 5(4), 293-305.

Haines, S., Summers, J., Turnbull, A., Turnbull, R., Palmer, S. (2015). Fostering Habib’s engagement and self-regulation: A case study of a child from a refugee family at home and preschool. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35(1), 28-39.

Hos, R. (2020). The lives, aspirations, and needs of refugee and immigrant students with interrupted formal education (SIFE) in a secondary newcomer program. Urban Education, 55(7), 1021-1044.

Inks, M. J. (2021). Educational experiences of Congolese refugees in west-central Florida high schools. (Publication No. 21) [Master’s thesis, University of South Florida]. Scholar Commons.

Joycea, L., & Liamputtong, P. (2017). Acculturation stress and social support for young refugees in regional areas. Children and Youth Services Review, 77(1), 18-26.

Mahoney, D., Baer, R., Wani, O., Anthony, E., & Behrman, C. (2020). Unique issues for resettling refugees from the Congo wars. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 44(1), 77-90.

Mcneely, C., Morland, L., Doty, B., Meschke, L., Husain, S., Nashwan, A. (2017). How schools can promote healthy development for newly arrived immigrant and refugee adolescents: Research priorities. Journal of School Health, 87(2), 121.

Mendenhall, M., Bartlett, L., & Ghaffar-Kucher, A. (2016). If you need help, they are always there for us: Education for refugees in an international high school in NYC. Urban Affairs Review, 4(2), 1-26.

Moskalenko, S., & McCauley, C. R. (2020). Radicalization to terrorism. What everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press.

Nugent, G. (2021). Colonial legacies: Contemporarylens-based art and the democratic republic of Congo. Leuven University Press.

Nyamnjoh, H., Hall, S., & Cirolia, L. (2021). Precarity, permits, and prayers: Working practices of Congolese asylum-seeking women in Cape Town. Africa Spectrum, 4(3). 1-20.

Oliveri, M., & Wendler, C. (Eds.). (2020). Higher education admission practices: An international perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Onchwari, G., & Keengwe, J. (2019). Handbook of research on engaging immigrant families and promoting academic success for English language learners. Information Science Reference.

Stillman, J., Anderson, L., Beltramo, J. L., & Gomez-Najarro, J. (2017). Teaching for equity in complex times: Negotiating standards in a high-performing bilingual school. Teachers College Press.

Surowiec, P., & Manor, I. (2021). Public diplomacy and the politics of uncertainty. Palgrave Macmillan.

Torres, J. A. (2018). Famous immigrant athletes. Enslow Publishing.

Wabia, C. (2020). The cultural influence on mass customization. Springer Gabler.

Wachter, K. (2016). Unsettled integration: Pre- and post-migration factors in Congolese refugee women’s resettlement experiences in the United States. International Social Work, 59(6), 875-889.

Wearne, E. (2021). Defining hybrid homeschools in America: Little platoons.

Wilkinson, J., & Langat, K. (2012). Exploring educators’ practices for African students from refugee backgrounds in an Australian regional high school. The Australasian Review of African Studies, 33(1), 1-21.