Depending on the amount of money set aside, healthcare treatments and practice methods fluctuate from country to country. The country’s economic and political institutions also influence healthcare allocations. Developed countries will have superior health infrastructure and will employ conventional medicine, which is a system in which most medical practitioners use medications, surgery, or radiation to treat the signs and symptoms of an illness. Western medicine is another name for it. Wealthy countries like the United States have advanced healthcare technology, demonstrating how they spend more on healthcare (Smith-Bindman et al., 2019). This will be different in developing countries, where funding would be stretched to cover activities and care for their patients. These countries may use naturopathic or holistic medicine, such as treating hypertension with exercise and possibly a diet change. As a result of the absence of healthcare infrastructure for its citizens and in satisfying their medical demands, emerging countries and their healthcare systems face particular obstacles.

Healthcare is an industry that focuses on the entire and holistic restoration of life, which encompasses the emotional and physical well-being of a person. It becomes easier to manage a condition when it is prevented and treated, and the most vital components of an individual’s well-being are taken care of by skilled medical professionals. Developed countries, which are deemed industrialized, may have a more sophisticated system than other countries due to differences in economic and political stability (Aluko-Arowolo, 2021; Hong et al., 2020). It is, however, contingent on a country’s ability to provide physical and mental well-being to its population in a safe and healthy environment.

The major factors for measuring health disparities between countries are a country’s financial allocation to healthcare, population health, and how well the system responds to avoid fatalities and make healthcare affordable for all. Because of their lack of infrastructure and quality services, developing countries may have difficulty delivering healthcare to their citizens due to economic instability. They, therefore, struggle to offer effective treatment and services, and improving the medical services offered is challenging, forcing them to rely on socio-cultural resources for treatment (Nwokeke and Oyefara, 2018).

There is also a shortage of human resources in most countries that are developing, like Nigeria, therefore affecting the number of doctors and related professionals taking care of patients. The few that are there sometimes may be inadequately trained or may lack general equipment, further frustrating them. Such strains faced by the healthcare professionals in developing countries lead to a medical brain drain. As seen in Africa, which bears close to 24% of the global disease body, only has 3% of healthcare workers caring for the sick (Ighobor, 2017). Though the issue of a lack of human resources has been a continuing challenge, the global COVID-19 worsened the state of healthcare, further exposing the loops in the African healthcare systems. The increase in brain drain, as many health professionals migrate to wealthy nations such as the United States and the United Kingdom, is the main factor contributing to the lack of healthcare workers. A lack of resources and facilities, and a lack of access to equipment hinder the efforts at saving lives when needed the most.

As recommended by the World Health Organisation, the ideal doctor to population ratio is 1:1000 people. In Africa, however, due to the low ratio of its professionals, the number of patients rises to 5,000 per doctor. By 2025, this number is expected to even be higher. Using an example in the United Kingdom, which has a population of about 70 million, there are more than 370,000 physicians while Nigeria, with over 211 million people has less than 75,000 physicians (Kumar and Pal, 2018). Many doctors work in the UK with 86% of African graduates looking at the United States for employment. Many who are mostly from the Western parts of Africa find employment and never return apart from physicians. In developed countries, close to 24% of registered nurses and another 20% of their assistants are from African countries (Akinfenwa, 2021). The biggest contributor to the shortage of healthcare workers is the growth in brain drain, as many health experts migrate to wealthier countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom. Other developed countries such as Australia, Saudia Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have also sustained a relatively high number of physicians to population ratio. They also offer African medical graduates employment.

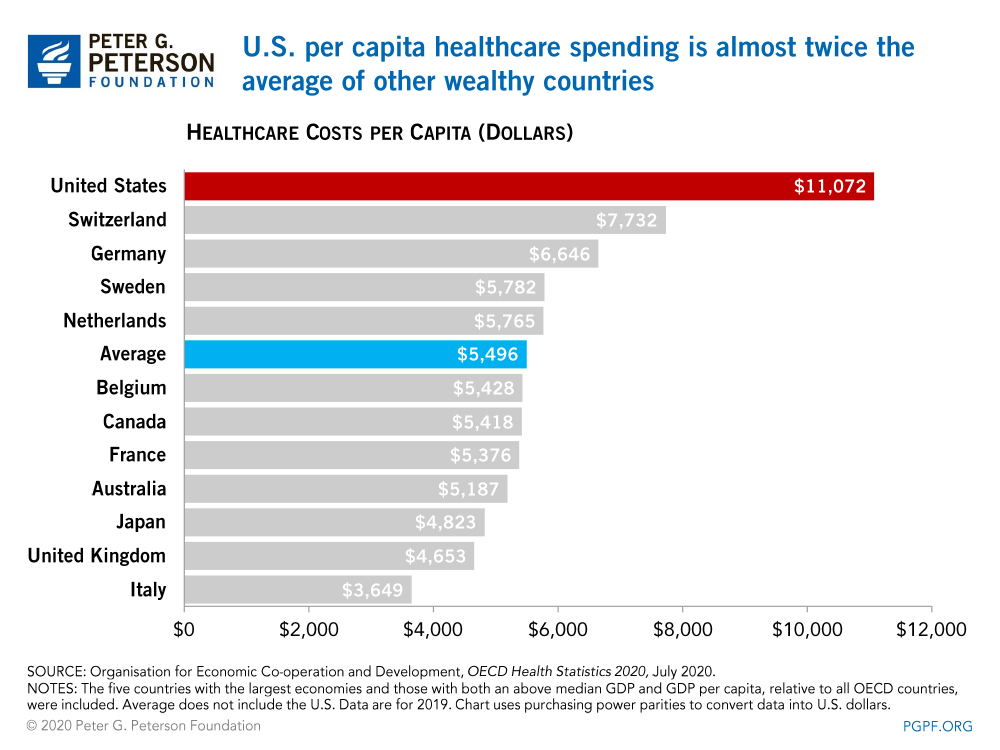

Considering this growing concern in regards to the continent’s state and the healthcare systems, there is a growing trend of medical graduates going to developed countries requiring an immediate solution. If not, the problem could impact the whole continent and the effects will be beyond the country’s economic growth. The other driving force behind the particular African healthcare challenge is the better pay, as well as the opportunity to learn new things and practice in facilities with better equipment. They further follow the opportunity to develop and further their knowledge and avoid having to deal with the lack of or poor infrastructure and the bleak future of the population (Fagite, 2018). Due to the mass migration, there have been medical and financial implications for the African countries (Cawley and Hooker, 2018). Africa, having only 16% of the global population and spending less than 1% of the total global health expenditure, is very different from industrialized countries which spend ten times more on healthcare (Ogbuoji et al., 2019). Furthermore, Ighobor (2017) posits that on average, surgeons in the United States and New Jersey make around $216,000 annually average, while their African colleagues in Zambia earn around $24,000 and Kenya earn around $6,000.

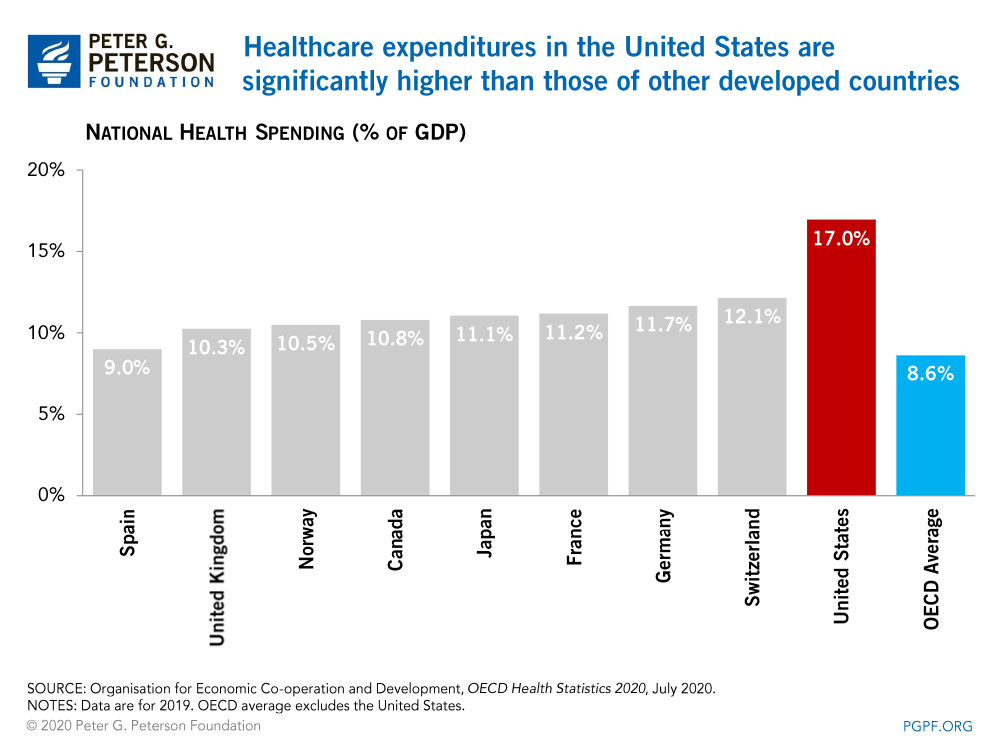

A more developed healthcare system like that of Canada is more universal coverage, has cheaper drugs making it affordable to its population. Canada’s healthcare system is also efficient and equitable. According to research by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation in 2017, it is estimated to have spent around 10.4% of its GDP on healthcare with America doubling the number (Peter G. Peterson Foundation, 2020; Martin et al., 2018). Access to healthcare in such a country is therefore not a problem, therefore adequately catering to the medical needs of the aging population, children, and those with chronic illnesses. There is also the availability of professional services, and affordable medication to cater to its population.

Unlike developing countries, developed countries have the appropriate infrastructure and staff working in a more developed environment with better opportunities for them. They, therefore, are in the right mental capacity to handle patients and offer them quality effective treatment further improving their access to healthcare. Though in a country like the US where healthcare spending is high, it is due to factors such as the number and prices of services used, though prices are generally considered high despite these utilization rates.

Reference List

Akinfenwa, O. (2021) ‘Africa’s loss, their gain: How the US and UK benefit from medical brain drain’, GlobalVoices, Web.

Aluko-Arowolo, S. (2021) ‘An exploration of health care delivery in rural areas of South Western Nigeria’, KIU Journal of Humanities, 6(1), pp.23-30.

Cawley, J.F. and Hooker, R.S. (2018) Determinants of the physician assistant/associate concept in global health systems. International Journal of Healthcare, 4(1), pp.50-60.

Fagite, D.D. (2018) Nigerian nurses on the run: Increasing the diaspora and decreasing concentration. Journal of Pan African Studies, 12, pp.108-121.

Hong, A.S., Levin, D., Parker, L., Rao, V.M., Ross-Degnan, D. and Wharam, J.F. (2020) Trends in diagnostic imaging utilization among medicare and commercially insured adults from 2003 through 2016. Radiology, 294(2), pp.342-350.

Ighobor, K. (2017) Diagnosing Africa’s medical brain drain. Africa Renewal, 30(3), pp.8-9.

Kumar, R. and Pal, R. (2018) India achieves WHO recommended doctor population ratio: A call for paradigm shift in public health discourse! Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 7(5), p.841.

Martin, D., et.al (2018) Canada’s universal health-care system: achieving its potential. The Lancet, 391(10131), pp.1718-1735.

Nwokeke, C.C. and Oyefara, J.L. (2018) Influence of sociocultural factors on the health seeking behaviour of patients with bone fracture in Lagos State, Nigeria. African Journal for the Psychological Studies of Social Issues, 21(1), pp.1-20.

Ogbuoji, O., Bharali, I., Emery, N. and McDade, K.K. (2019) Closing Africa’s health financing gap. Future Development. Web.

Peter G. Peterson Foundation. (2020) How does the US healthcare system compare to other countries? [Graph].

Smith-Bindman, R., et al (2019) Trends in use of medical imaging in US health care systems and in Ontario, Canada, 2000-2016. Journal of the American Medical Association, 322(9), pp.843-856.