China’s economy has been the world’s fastest expanding, Since the 1980s. It took over four decades for China to begin economic reforms and trade liberalization. The “fastest sustained expansion by a large economy ever,” the World Bank said. Since 1979, when it opened its doors to foreign commerce and investment, China’s economy has grown rapidly. China has become America’s top trading partner. China’s third-biggest export market by buying US Treasury bonds helps keep rates low. China’s expanding global economic power and trade policies worry politicians. Chinese industry restrictions and intellectual property theft have resulted in anti-American actions such as industrial controls and intellectual property theft. China has transformed itself into a global economic behemoth in the previous 40 years. From 1979 through 2017, China’s real GDP increased by roughly 10% (Walter,29). China has become a worldwide economic capital. On the list of major economic powers China and the United States are leaders.

The Chinese economy’s rise has boosted US-China commerce. It grew from $5 billion to $660 billion in 2018. In terms of trade, China is America’s third-largest market. As a result of the booming Chinese market and cheaper labor for export-oriented production, some American companies have large operations in China. These operations have made low-cost goods available to American customers—huge Chinese Treasury bond purchases. Many US leaders fear China’s economic rise. Accused By flooding the US market with low-cost items, China threatens US jobs, wages, and standards of living. Others argue that China’s increasing use of industrial policies to promote and protect state-favored local sectors and firms harms IP-intensive industries like medicine and electronics. Numerous trade and investment impediments prevent US exports to China.

The Chinese government says economic growth is required to sustain social stability. However, China’s economic problems could slow future growth. Poor banking, growing inequality, pollution, and a lack of legal protections are just a few examples. According to the Chinese government, other efforts include expanding social security coverage, supporting the development of less polluting sectors, and combating official government corruption (Von Glahn, 345). China’s capacity to implement changes will likely determine whether it can maintain modest growth rates or start slowing down.

Chinese involvement in global economic policies and operations, particularly infrastructure construction, has increased. In Asia, Europe, Africa, and beyond, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) seeks to fund infrastructure. China’s export and investment markets may dramatically expand if China’s economic policies succeed and its global “soft power” grows. The IMF predicts an economic slowdown by 2024. It is the “new normal” in China, say the officials. The new economic model prioritizes private consumption, services, and innovation over fixed investment and exports. Unable to adopt new growth techniques, countries fall into the “middle-income trap.”

China’s rapid economic expansion has outpaced the country’s institutional development. The country still has significant institutional and reform gaps to close to maintain a high-quality and sustainable growth path. The state’s role must change and be focused on delivering stable market expectations and a clear and fair business climate, as well as enhancing the regulatory system and the rule of law to further support the market system, according to the World Economic Forum. China’s influence on other developing economies is growing through trade, investment, and ideas. Many of China’s challenging development difficulties are shared by other nations, such as aging, developing a cost-effective health system, and encouraging a low-carbon energy pathway.

A key component of such a transformation is reducing the disparity in economic prospects for men and women. According to the Financial Times, the government has identified attaining common prosperity as a fundamental economic priority, but it has not yet outlined particular policies to achieve this goal. In addition to protecting the most vulnerable, more progressive taxation and a reinforced social safety system might assist reduce inequality while also boosting private consumption as a driver of growth.

During the reform period, the fast mobilization of resources and the transfer of control from public to private ownership aided the high growth rates. This allowed for greater efficiency in the administration of such resources. This period of tremendous resource mobilization is now coming to an end, and China will have to rely more on efficiency gains in the future if it wants to continue growing its economy (De Bary et al.316). Inequalities in economic, social, and environmental outcomes have increased due to China’s rapid economic growth based on resource-intensive manufacturing exports and low wages. The economy must shift from manufacturing to high-value services and from investment to consumption to reduce these inequities.

Chinese economic progress has been astonishing and chaotic since the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949. As a result of the revolution, socialism, and Maoism that occurred during this period, it has seen progressive economic reform and rapid economic growth that has been characteristic of the post-Maoist era. China’s economy suffered greatly during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution (De Bary, 511). Chinese living standards have significantly improved since the period of economic reform began in 1978, and the country has had relative social stability during this period. China has progressed from being an isolated socialist state to becoming the world’s economic backbone throughout that period. Structural constraints have hindered growth, limiting labor force growth, investment returns, and productivity. New economic drivers will be tough to find while dealing with the social and environmental implications of China’s previous development path.

China is a major player in many regional and global development issues. China now emits more greenhouse gases per person than the European Union (Mohajan,196). Its emissions are slightly below the OECD average and far below the United States, but its pollution affects other countries. It is impossible to solve global environmental problems without the involvement of China. China’s expanding economy is also a significant source of global demand, and the country’s economic rebalancing will open up new prospects for manufacturing exporters while also reducing demand for commodities over the medium term. Growth is expected to slow in 2022 to 5.0 percent, down from an annualized rate of 8.1 percent in 2021 (Sisko,595). The prediction reflects increasing headwinds: With the Ukrainian conflict’s outbreak, domestic demand has slowed, and the global economic climate has deteriorated dramatically. Aside from that, COVID invasions have gotten more frequent and extensive in recent years. Since the end of the national lockdown in March 2020, China has been experiencing the strongest COVID wave.

China’s Economic Growth and Reforms: 1979-the Present

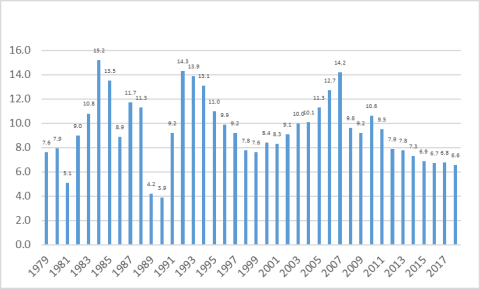

Chinese GDP has increased far faster than previous reforms and has avoided severe economic shocks in recent years. 10 It expanded at a 9.5% annual pace from 1979 to 2018. The Chinese GDP might so double in eight years. It was affected by the economic crisis; 20 million migrant workers went home in the first quarter of 2009. In response, a $586 billion stimulus program to enhance bank lending and support infrastructure development was launched in China. These policies helped China counteract the substantial decline in worldwide demand for Chinese commodities. China’s real GDP grew 9.7% between 2008 and 2010. Following the US Section 301 action and Chinese responses, many experts believe China’s economic progress will continue to decline in 2021-2022; tariff rises on all trade between the US and China may produce a 1.1 percent decline in the country’s GDP.

Chinese Annual Real GDP Growth: 1979-2018(percentage change)

Causes of China’s Economic Growth

Large-scale capital investment and high productivity growth are two major drivers of Chinese economic success. These two aspects seem to be linked. Overall, economic reforms increased output and made resources available for longer-term investment. Savings have always been popular in China. Domestic savings accounted for 32% of GDP when the reforms were introduced in 1979. China’s savings during this period were primarily comprised of SOE profits, which the central government used to fund domestic programs. Household and company savings have risen due to China’s economic reforms, particularly manufacturing decentralization. Local savings have permitted major investments. With more savings than investment, China is a big global lender.

According to several experts, productivity improvements have also contributed to China’s rapid economic rise. The increasing production impacted all sectors of the economy, including agriculture, trade, and services. According to the World Bank, changes in agricultural production, for example, enhanced output while freeing up people to work in more productive manufacturing industries. On the other hand, the centrally controlled SOEs became less market-oriented and less efficient as China’s economy became more decentralized. In addition, the economy became more competitive. It was entirely up to local and provincial governments to form and run businesses. It also provided new technology and procedures that improved manufacturing. Without becoming a key hub for new technologies and undertaking significant economic reforms, its productivity gains and real GDP growth could decrease dramatically when its technical progress converges with that of the main industrialized countries. Several emerging countries saw rapid economic expansion in the 1960s and 1970s due to policies similar to China’s, such as measures to increase exports and measures to stimulate and safeguard critical sectors, among other things. However, throughout their development, some of these countries slipped into a trap known as the “middle-income trap,” which economists refer to as a state of economic stagnation.

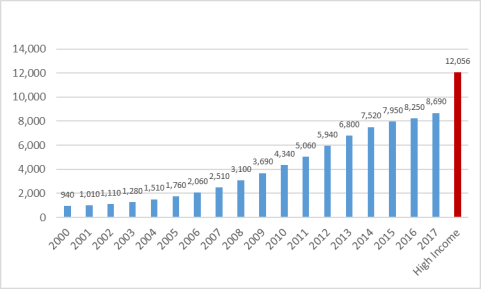

World Bank’s Per Capita China

The red bar represents the high-income threshold for China.

Measuring the Size of China’s Economy

The “actual” magnitude of China’s GDP has long been questioned. As estimated by the IMF, China’s GDP was $13.4 trillion in 2018. On the other hand, China’s nominal GDP per capita was $9,608 in 2018. Chinese economic and living standards are distorted as a result of the use of nominal exchange rates to transfer data from China into dollars. However, it is crucial to note that nominal exchange rates do not consider variations between nations in the cost of various goods and services. A dollar in China bought more products and services than in the US. However, because China’s goods and services are cheaper, Japan’s prices frequently exceed US pricing. For every dollar swapped for yen, Japan’s economy loses out. Achieving purchasing power parity with the dollar is an attempt to estimate exchange rates. Gross domestic product and GDP per capita in China increased by 49.2% in 2016. According to the IMF, its prices are half those in the US. For the first time, the IMF reports that China surpassed the US in 2014.

According to the World Bank, Chinese manufacturers have surpassed all other countries in terms of production. GDP numbers indicate the importance of manufacturing. Exports of manufactured goods from China outperformed those from the US in 2016. Chinese GDP is heavily industrialized compared to the US. On the other hand, the US had 11.6 percent gross value-added manufacturing in 2016, while China had 28.7%.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in China

In the early 1990s, China opened its markets to foreign direct investment. Such influxes have contributed to China’s rapid economic and commercial development. In 2010, 445 foreign-invested enterprises employed approximately 2 million people in China. A large proportion of China’s output is produced by foreign-owned firms (FIEs). The population percentage ranged from 35.9% in 2003 to 25.9% in 2011. Exports from China are also heavily dependent on foreign-owned firms. Exports and imports by foreign-owned companies (FIEs) reached a peak in 2005, accounting for 58.3 percent and 59.7 percent of total exports and imports, respectively.

Factors Driving China’s FDI Outflow Strategy

China’s vast foreign exchange helps to increase investment. This money has traditionally been placed in safe but low-yielding assets like US Treasury bonds. On September 29, 2007, China established the China Investment Corporation to maximize profits. The need for natural resources partly drives growth in FDI outflows to power China’s fast financial growth. Finally, China seeks worldwide Chinese brands. Chinese enterprises consider acquiring foreign technology, management capabilities, and global brands. For IBM’s computer division in April 2005, Lenovo paid $1.75 billion.

Major Long-Term Challenges Facing the Chinese Economy

Current efforts are being made to modernize China’s economic paradigm. Politics aimed at attaining rapid economic expansion at all costs have historically been highly successful. Many economists argue that the old growth model is no longer viable because of the costs associated with such endeavors. China has made significant strides in this direction to build a new growth model that stresses individual consumption and innovation as new economic drivers. A new sustainable development model may be difficult to build unless China successfully implements new economic reforms. Many experts fear that China could fall into the “middle-income trap,” where economic growth and living standards will stagnate without such reforms.

Challenges

Heavily energy-intensive and polluting industries have prioritized China’s economic growth strategy. Public health is being jeopardized as China’s pollution continues to worsen. As part of its efforts to spur economic growth, the Chinese government often violates environmental regulations. From 2000 to 2016, according to ExxonMobil’s projections, China accounted for over 60% of the increase in global CO2 emissions, and its emissions will surpass those of the US and the European Union. Over-borrowing and pollution are major threats to China’s economy. Macroeconomic policies must avoid escalating financial risks. We need structural changes to re-energize the shift to balanced, quality growth.

Works cited

De Bary, Wm Theodore, and Richard Lufrano, eds. Sources of Chinese Tradition: From 1600 through the twentieth century. Columbia University Press, 2001.

De Bary, Wm Theodore, and William Theodore De Bary, eds. Sources of East Asian Tradition: Premodern Asia. Vol. 1. Columbia University Press, 2008.

Mohajan, Haradhan. “Greenhouse gas emissions of China.” (2013): 190-202.

Sisko, Andrea M., et al. “National health expenditure projections, 2018–27: economic and demographic trends drive spending and enrollment growth.” Health affairs 38.3 (2019): 491-501.

Von Glahn, Richard. An economic history of China: From antiquity to the nineteenth century. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Walter, Carl E. “Was Deng Xiaoping Right? A 40‐Year Assessment of China’s Adoption of Western Capital Markets.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 33.4 (2021): 24-38.