Abstract

Diesel and gasoline are derived from oil, a black, gloopy material generated from the fossilized remains of plant and animal life that existed and perished hundreds of millions of years ago under our oceans. Oil includes carbon molecules, and when it is burnt in a car engine. It creates carbon dioxide (CO2), the most abundant ‘greenhouse gas’ in the earth’s orbit. CO2 concentrations in the universe’s atmosphere have increased dramatically in recent years. Almost all climate change scientists now believe that higher CO2 levels in the atmosphere are caused by increased fossil energy use.

Since lithium-ion batteries are lightweight, have a low power density, offer superior battery efficiency, and have a higher energy output, they are employed as the primary energy source in electric cars. Electric energy has emerged as an alternative source for the automobile sector due to the depletion of fossil fuels and rising temperatures. There are concerns about the safety of lithium-ion batteries and their impacts on the environment.

Much research is being done to make the batteries safer for health and more eco-friendly. Electric vehicles are becoming more prevalent, and if this trend continues, the number of electric cars may outnumber gasoline-fueled vehicles. This paper will compare the total environmental effect of generating lithium batteries for electric automobiles to producing fossil fuels for gasoline-powered cars to determine if the benefits outweigh the cost.

Introduction

Electrochemical energy storage technologies are being used to electrify vehicles and progressively integrate intermittent renewable energy sources into the larger electrical grid to minimize greenhouse gas emissions. Due to their historically declining costs, relatively high energy densities, and rising manufacturing, lithium-ion technologies are seen as the most promising of all battery types. In terms of USD kW1 h1, the actual cost of lithium-ion batteries has decreased by around 97% since their introduction in 1991 (DeMeuse 15). Progress toward a more economically sustainable environment to lower CO2 and other greenhouse emissions has increased due to the ongoing climate change.

Although CO2 is not produced when electric motors are in operation, it is created when electric vehicles (EVs) collect power from the grid and store it in their batteries. Throughout its life, an entirely electric automobile emits around 35% fewer CO2 emissions than a gasoline-powered vehicle (Newburger). The usage phase makes up for the considerably greater emissions linked to an electric car and its battery’s manufacture. In general, emissions produced during fuel generation and vehicle use are lower in electric cars. Yet, the production of electric vehicles frequently has more emissions than a typical car.

Electric vehicles may lower CO2 emissions less than conventional autos in high-carbon electricity networks due to their dependency on the CO2 intensity of power generation. An average electric car in Europe produces 29% fewer greenhouse emissions throughout its lifetime than a car with the most effective internal combustion engine (DeMeuse 18). As a result, sustainable mobility must use as much renewable energy as possible to power electric cars. The level of carbon concentration emissions in the regional energy business varies by country.

Subject to the current energy mix, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that switching from a conventional automobile to a battery-electric car after ten years will reduce lifetime emissions in the European Union by 80% (Yang et al. 533). The numbers for the United States are 60%, and for China, they reach about 40% (Yang et al. 533). To accelerate the electric mobility shift, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) developed the electric mobility calculator.

Compared to fossil fuels for gasoline vehicles, electric vehicles may reduce the emission of more than 40 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the climate between now and 2060 (Lodhia 159). It is anticipated that 5% of all private transportation will be battery-electrical by 2050 (Yang et al. 533). By that time, they would, in the best-case scenario, account for 60% of all private automobiles (Nieto).

In 2015, the Paris Agreement was developed to build the foundation for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 to mitigate climate change (Yi and Shirk 53). The sale of new gasoline-powered automobiles will no longer be allowed in California, the nation’s most populous state, beginning in 2035 (Newburger). These decisions are paving the path for other states to follow suit and are anticipated to have significant effects outside California. Since then, 17 more states have joined California in enacting the Clean Air Act’s requirement for electric vehicles (Lodhia 170).

As one examines this current trajectory, is the global economy moving towards a more sustainable future? This paper is a cost analysis of the environmental impact of manufacturing lithium batteries for use in electric vehicles compared to producing fossil fuels for gasoline vehicles. The literature review will analyze the potential long-term damage with lithium batteries and the lithium mining areas in relation to the benefits of lowering greenhouse emissions through alternative energy solutions.

Literature Review

Bernhart, Wolfgang. “Recycling of Lithium-Ion Batteries in the Context of Technology and Price Developments.” ATZelectronics Worldwide, vol. 14, no. 1-2, 2019, pp. 38–43, Web.

Bernhart states that worldwide lithium scarcity is expected to raise the price of the mineral. Lithium costs reached an all-time high of $77,000 per ton in March 2022 (Bernhart 41). Several reasons have contributed to the price increase, including rising energy costs, which have increased the attraction of the energy transition, soaring demand for electric vehicles (EVs), and the rapid development of rechargeable battery technology.

However, because the distribution network depends on Chinese firms to prepare the material for commercial usage, battery manufacturers are currently dealing with severe lithium scarcity. There is rising pressure on Western manufacturers to ensure the supply of EVs and lithium-ion batteries because China now controls 70%–80% of the distribution chain (Bernhart 41). This has prompted many EV producers, like Ford and Tesla, to investigate alternative sources of supply via direct contracts with businesses and investments in novel extraction techniques, such as direct lithium extraction (DLE).

It is anticipated that the reserves of new extraction techniques will play a key role in supplying the extra lithium needed to meet the rising demand. Despite these steps to support supply, there is still skepticism within the sector that adequate price management can be implemented, and new supply chains can be established. Many novel extraction techniques also need to be relatively high for commercial application. For the coming years, EV and battery manufacturers will be held responsible for a tiny supplier network until they are, adding pressure to the supply chain and making it vulnerable to sudden price hikes.

DeMeuse, Mark T. “Introduction to Lithium-Ion Battery Design.” Polymer-Based Separators for Lithium-Ion Batteries, 2021, pp. 1–19, Web.

The scholar states that most current electric vehicles use a lithium-ion battery pack to store energy. Although alternative battery technologies, such as solid-state cells, are anticipated to power the propellers of electric automobiles in the future, the infrastructure for massive battery production now favors lithium batteries. First, li-ion cells have more energy density than traditional rechargeable batteries, which operate the generators in most modern automobiles, or nickel-metal hydride batteries (DeMeuse 3). They are now used in many hybrid vehicles, including those made by Toyota.

Secondly, lithium cells self-discharge more slowly than other types of batteries. Third, lithium-ion batteries can have their electrolytes maintained or subjected to regular complete discharges. Lastly, lithium-ion batteries deliver more stable voltage even when the charge deteriorates.

Although using lithium-ion batteries in electric cars has numerous advantages, there are also some disadvantages. Producing lithium batteries is costly, and extracting the cobalt and nickel needed to build these energy storage systems is fraught with ethical and environmental dilemmas. Furthermore, the lifespan of lithium-ion batteries depends on integrated battery control.

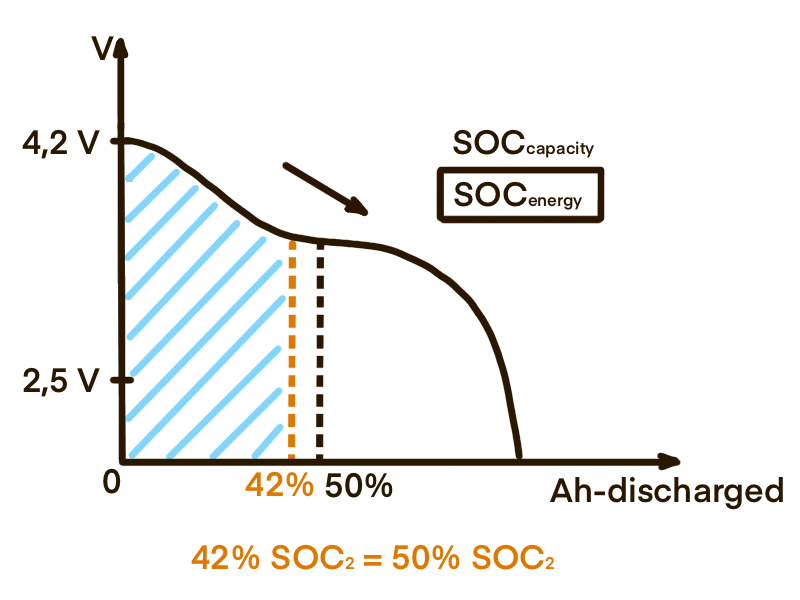

Ways to extend the lifespan of the battery are shown in Figure 1. Lithium-ion battery life is also shortened by fully charging and draining them. They tend to overheat and burst into flames; however, the likelihood is relatively low. Finally, high temperatures impact how lithium-ion batteries charge and discharge; the battery discharge process is presented in Figure 2.

Dorn, Felix Malte, et al. “Mining Companies, Indigenous Communities, and the State: The Political Ecology of Lithium in Chile (Salar De Atacama) and Argentina (Salar De Olaroz-Cauchari).” Journal of Political Ecology, vol. 29, no. 1, 2022, Web.

This article focuses on the fact that Communities lose accessibility to drinkable water as mining activities make an already arid terrain much drier, forcing them to depend on tankers to provide it. Although its supplies are depleting, most of Chile’s lithium mining has taken hold in the Atacama Desert salt flat, adjacent to the border zone with Argentina and Bolivia. The Chilean mine, known as Salar de Atacama, contains 33% of the lithium that is now known to exist (Dorn et al.). The lithium base of the nation is located within the 55 km long solar (Dorn et al.). Presently, Chile is the top provider of lithium in the world. Lithium quarrying in Chile has negative environmental consequences, such as decreased water supplies, loss of biodiversity, disruption of regional ecosystems, and polluted soil and groundwater.

Finsterbusch, Martin, and Chih-Long Tsai. “Advanced Lithium and Lithium-Ion Batteries.” Lithium-Ion Batteries, 2019, pp. 41–68, Web.

In Finsterbusch’s and Tsai’s opinion, China has significantly contributed to the rise in global Carbon outputs before the COVID-19 pandemic. Only one other major economy, China, had growth in 2019 and 2022 (Finsterbusch and Tsai 42). Across those two years, China’s gas emissions increased, more than offsetting the global drop in pollution overall. China’s CO2 emissions exceeded 9 billion in 2020, making up over 23% of global pollution (Finsterbusch and Tsai 57). A significant spike in electricity consumption mainly relied on coal power, which was a major contributor to China’s emission rise.

India’s Emissions of CO2 had a substantial resurgence in 2021, surpassing 2019 levels because of an increase in coal usage for energy production (Finsterbusch and Tsai 64). In India, coal-fired power increased to an all-time high, rising 13% over its level in 2020 (Finsterbusch and Tsai 51). In 2021, the developed nations’ global commercial production returned to its pre-pandemic heights, but carbon dioxide emissions did not recover as quickly, indicating a more persistent systemic decrease (Finsterbusch and Tsai 53).

Jing, Ran, et al. “Assessments on Emergy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Internal Combustion Engine Automobiles and Electric Automobiles in the USA.” Journal of Environmental Sciences, vol. 90, 2020, pp. 297–309, Web.

The Jing et al.’s extensive research, based on the most recent official national statistics and readily accessible power, financial, and meteorological data, provided the basis for estimating the world’s CO2 outputs and energy consumption. The latest study demonstrates that global gas releases from fuel increased to their top level than ever seen in 2019 (Jing et al. 283). This is supported by projections of methane releases released by Jing et al. last month and estimations of N2O and CO2 outputs attributable to flaring.

For most of 2021, the operational costs of conventional coal production facilities were much cheaper than those of gasoline energy plants throughout the U.S. and several necessary European infrastructures (Jing et al. 301). Changing from gasoline to coal increased carbon dioxide emissions from power production by well over 100 million metric tons globally (Jing et al. 288). That was particularly noticeable in the US and Italy, where coal and natural gas power stations face the most rivalry.

Lodhia, Sumit K. “Sustainability Reporting in the Mining Industry.” Mining and Sustainable Development, 2018, pp. 158–175, Web.

The author admits that the water levels in Salar de Atacama in Chile have been declining over the last five years. This might cause droughts and contribute to specific parts becoming deserts. The varied assortment of microorganisms present in saltwater will affect every aspect of the biological system.

Chilean, Andean, and James’s flamingos are some areas that take summer vacations in Bolivia to let off steam and reproduce (Lodhia 166). A field report was published by ecologists Marita Davison and Jennifer Moslemi, who investigate flamingos in the lakes of the Altiplano. Due to their quickly interrupted nesting habits, these birds—whose vivid pink plumage makes them famous and beautiful—are already in danger. If the Salar loses all of its water, it could become extinct. The negative effects of lithium mining, including water depletion and decreased biodiversity, also significantly impact the surrounding community.

Mamo, Tadele, and Fu-Kwun Wang. “Attention-Based Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Network for Capacity Degradation of Lithium-Ion Batteries.” Batteries, vol. 7, no. 4, 2021, p. 66, Web.

Scholars discuss the benefits of using Lithium batteries, which have prompted the use of lithium cells in aircraft, defense, and electric motor uses. As a result, it is anticipated that the worldwide industry for lithium cells will grow from $8.9 billion in 2009 to $6.6 billion in 2016 (Mamo and Wang 66). Reusable lithium cells used in mobile electronics have a relatively finite lifespan of between two and four years. This will significantly add to the rising issue of digital trash, the US municipal waste stream sector that is developing at the quickest rate.

Metals like tin, nickel, and arsenic, as well as organic compounds like poisonous and combustible solutions like LiBF4 and LiPF6.4, are all in lithium cells and may be hazardous. Lithium battery manufacturing is typically governed by vocational health and protection laws, and possible fire dangers affiliated with their commuting are governed by the US Code of National Laws. Still, there needs to be a uniform policy regarding what happens to lithium chargers that are disposed of in e-waste dispersed worldwide.

Malfunctions and mishaps with computers, pads, PCs, cell phones, and handsets frequently cause life-threatening circumstances. The Honeywell organization stopped producing and delivering two mobile multi-gas sensing gadgets as a safety feature after customers complained about superheated lithium fuel cells. This was the newest detrimental development in a long string of lithium electronics occurrences. First, it stopped producing and then announced the discontinuation of the Samsung Note 7, an unparalleled disaster in the mobile phone industry. Buying and shipment constraints would still be available as declared by the organization.

Large-scale issues have been detected in the districts close to Tibet’s Rongda lithium production. In 2017, when a hazardous material release from the mine caused a significant discovery of rotten fish in the neighboring Liqi Riverbed, protesters from the neighboring village of Tagong went to the markets (Mamo and Wang 66). The region has experienced a rapid increase in industrial operations in the past few days, resulting in two catastrophes of this nature in only seven years. After ingesting the contaminated water, Dead Sea animals and other animals have been discovered. One of the manufacturing firms in the region is the Chinese automobile company, the world’s leading producer of rechargeable batteries for cell phones and other types of gadgets.

Chile, the second-largest supplier of lithium globally after Australia, is experiencing dire negative repercussions of manufacturing. Miners first drill tunnels into seashores to transfer salt water rich in minerals and salt to the exterior. After leaving the perforations for up to 17 months to let the solution evaporate, the lithium bicarbonate may be collected and converted into lithium metal. However, with Hcl acid used in the lithium operation, this creates the possibility of a scenario like that found in Tibet, damaging local ecosystems and contaminating nearby pastures and streams. However, water use in lithium extraction is among the significant challenges in Chile. 3 00,500 liters of water are required to manufacture one tonne of lithium (Mamo and Wang 66). The silver-tinted metal cobalt has drawn worldwide interest and surfaced as a critical component of some businesses that will shape the world.

According to the authors, cobalt is essential to the production of batteries. Alongside lithium, copper, and chromium, cobalt is a crucial component in lithium batteries because it contributes to the transition metal solution that forms the electrode of the battery CELLS, where energy is produced (Mamo and Wang 66). For instance, a power system cell bank’s sustainability is gravely threatened even though an electric engine only needs 20kg of valuable material (Mamo and Wang 66). Globally, there are concerns that China might unexpectedly monopolize the chromium marketplace and take a more dominant position in producing rechargeable cells than satisfy many other countries.

The DRC (Congo), where an assortment of relevant parties is involved in a fierce competition for dominance over-extraction activities, is the source of around 60% of the globe’s cobalt (Mamo and Wang 66). There is no electrical car sector without DRC cobalt. 90% of the high-quality cobalt used in battery production worldwide is supplied by Chinese processors, fed mainly by feedstock from Government mines (Mamo and Wang 66). Who holds the balance of economic powerhouse in the automobile and battery banks industries will depend on who controls the essential raw elements, particularly cobalt, and the globe refining and production capability.

Most of the world’s lithium supply is buried under salt flats in the Lithium Triangle located in South America. The Lithium Triangle includes sections of the Argentine, Bolivian, and Chilean regions. However, it is also among the hottest areas on the planet. Mining operations in Chile used up 70% of the area’s freshwater, which significantly negatively influenced local producers and forced some towns to get water from other sources (Mamo and Wang 66). HCl acid is utilized in the lithium process, and waste materials sifted out of the salt water can seep from the absorption basins into the freshwater system.

The mining of lithium contaminates the atmosphere and damages the soil. Inhabitants of Argentina Lithium mining say lithium activities polluted waterways utilized for agriculture and watering by people and animals. Hills of used salt and channels in Chile deface the environment. China is one of the five major nations with the largest lithium deposits (Mamo and Wang 66). The most excellent lithium resource globally is in Queensland, where China’s Tianqi Li company has a majority share.

Newburger, Emma. California bans the sale of new gas-powered cars by 2035. Web.

A study published by Newburger states that global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions increased by 7% to 26.3 billion tons in 2020 (Newburger para. 5). Their all-time highs as the global financial system successfully recovered from the Covid-19 catastrophe and largely depended on coal to fuel that grows. According to Newburger’s analysis, the increase in global CO2 emission of about 2 billion tones was the most significant relative increase ever recorded and significantly offset the decline caused by the previous year’s pandemic (Newburger para. 9). Unfavorable climatic and economic factors notably the rapid prices for natural gas, contributed to the comeback in energy usage in 2021 and boosted the use of coal despite renewable alternatives seeing their fastest growth (Newburger para. 10).

Nieto, Maria J. “Whatever It Takes to Reach Net Zero Emissions around 2050 and Limit Global Warming to 1.5C: The Cases of United States, China, European Union and Japan.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2022, Web.

This article explains the concept of “net zero,” which occurs when the quantity of global warming that reaches the atmosphere matches the number of greenhouse gases absorbed by the atmosphere. The consensus of experts throughout the country is that to prevent planetary net emissions of CO2 from modern behavior must decrease by around 75% from 2010 levels by 2050 and eventually reach zero (Nieto para. 5). Since global heating and total CO2 output are negatively connected, the world will remain too hot if total concentrations are more significant than zero. This implies that the suffering brought on by the rise in global temperature will only become more effective as long as emissions continue.

Northeast Magazine (n.d.). Are electric car batteries bad for the environment. Web.

According to this magazine, fossil fuel vehicles squander thousands of more raw materials than their rechargeable electric equivalents. This phenomenon contributes to the case for why switching away from gasoline and diesel-powered cars would have a positive net ecological impact. According to Northeast Magazine, only around 20 kg (or about 20,000 liters) of raw materials would be lost during a lithium-ion battery used in electric cars after regeneration (Northeast Magazine para. 4).

Converting chemical energy in a power bank to electricity and back to chemical storage will dump some of it as waste heat. The quantity of material wasted when an electric car power bank is dumped is 300 times greater than that consumed by conventional gasoline engines (Northeast Magazine para. 13). According to the Magazine, in all processes, including energy production and fuel production, electric motors create 54% less carbon four oxides (Northeast Magazine para. 11). The misconception surrounding the overall carbon footprint of electric vehicles use of a lot of natural resources remains.

Compared to the gasoline used by fossil-fuel cars, which, unlike battery packs, cannot be reused, the raw material needs of energy storage systems are minimal. This is due to the fact that they depend on factors like electricity supply mixtures and gasoline quantum yield. That is why the fundamental resources needed to create power and fossil fuel were excluded from the estimates for the petroleum motor. Any accurate assessment of oil and natural gas commodities and lithium-ion batteries demonstrates that natural gases and oil commodities are the most harmful throughout the extraction, refining, transportation, and burning processes.

Oshnoei, Soroush, et al. “Novel Load Frequency Control Scheme for an Interconnected Two-Area Power System Including Wind Turbine Generation and Redox Flow Battery.” International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, vol. 130, 2021, p. 107033, Web.

In their study, Oshnoei et al. state that Asahi Kasei Co. in Japan created lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), which Sony Co. ultimately began selling in 1991 (Oshnoei et al. 107033). The history of the invention is presented in Figure 3. Lithium ions flow between the anode and cathode in a typical LIB cell, producing an electric current. Lithium ions from the cathode during charging are transported to the anode via a polymer separator (Oshnoei et al. 107033). The cell can now store energy as a result; power is generated during cell release when lithium ions in the anode travel back into atomic-sized holes in the cathode material (Oshnoei et al. 107033). The three critical parts of a lithium-ion battery cell are the anode, electrolyte, and cathode.

Rossi, Christopher. “Neoliberalism’s Contested Encounter with International Law in the Lithium Triangle.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2019, Web.

The scholar states that the Lithium Triangle comprises the three primary lithium producers in South America—Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia—and is home to 54% of the world’s lightest metal (Rossi para. 7). In Argentina, Ultra Lithium owns several lithium brine reservoir projects. A flagship project, the Laguna Verde site, spans over 8,000 hectares and 80 square kilometers and has been discovered to contain new high-quality lithium (Rossi para. 8). The majority of locations in Argentina are at a high elevation.

The most environmentally friendly method of mining lithium is through evaporation pools, where solar evaporation occurs over several months, which also generates potassium. The potassium chloride is mixed with the lithium chloride during a complex process, which increases the conductivity of the lithium. Argentina’s struggling economy is currently trying to benefit from its abundant natural mineral resources. The government has simplified the mining and exploring processes to encourage the lithium-ion batteries industry.

In Chile, the manufacturing of lithium has created a water shortage resulting in a water conflict. Brine, or saline lithium-containing water, is pumped by miners into huge ponds, where the evaporative cooling might take years to extract the lithium. The method depletes already limited water supplies, degrades wetlands, and harms residents. The privatization of minerals and water in Chile, which grants corporations control of specific regional resources, is a legacy of the Pinochet administration.

Schloter, Lukas. “Empirical Analysis of the Depreciation of Electric Vehicles Compared to Gasoline Vehicles.” Transport Policy, vol. 126, 2022, pp. 268–279, Web.

In his article, Schloter dwells on the damage caused by the extraction and excavation of habitats, which contaminate the air, soil, and groundwater and emit greenhouse gases. It burns hydrocarbons, damages the planet’s climate, and produces hazardous pollutants. Management of energy is essential since all gas supplies and techniques have some influence on the ecosystem.

An analysis of the ecological effects of internal gasoline vehicles and electric automobiles from 2010 indicated that the latter have far worse results (Schloter 275). The study considered the possibility of climate change, total energy consumption, and depletion of natural resources. Lithium and other battery elements may be reused, and old batteries from electric cars can retain energy for houses, structures, and electricity grids.

While cobalt, aluminum, copper, and nickel utilized in the cells have significant ecological effects, lithium was not shown to be an important climate problem for electrical car cells. For internal gasoline and electric cars, other automotive parts are made from materials that have ecological consequences. The type of energy utilized to recharge automobile batteries affects how much of an impact there is on the ecosystem.

Adverse consequences are far more pronounced when gasoline is the primary energy source than when hydroelectricity or green sources like wind and solar power are used. However, the effects are still less severe than filling automobiles with gas. The usage of lithium in the fast-growing market for electric vehicles and several other goods and technologies might result in a shortage of resources.

Wang, Jiexi, and Zhihao Guo. “Hydrometallurgically Recycling Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries.” Recycling of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries, 2019, pp. 27–55, Web.

Scholars admit that over time, the consumption and degradation of the electrochemical cell and anode/cathode active components inevitably cause lithium-ion batteries to have a lifespan that is partially preset and dependent on the operating circumstances. Mining limitations for lithium are being advanced, resulting in a significant rise in the environmental effect of mining itself. As a result, recycling lithium cells is becoming progressively crucial, particularly given the volume of batteries that will be manufactured and discarded in the future (Wang and Guo 35). The resources acquired by recycling can be substantial, preventing one component of pollution while partially compensating for a shortage of resources.

Lithium cells are recycled by shredding them and combining all of their constituents. Once all the metals have been incorporated into a powder, they must be sorted by either liquefied or decomposed in acid to recover the necessary metal. Since the recycling of cells is still in its initial phases, the United States has proposed an amendment to the Defense Production Act (Wang and Guo 28).

The purpose is to invest in obtaining the metals required for a sustainable energy revolution while simultaneously studying and investing in lithium-ion battery recycling. Instead of destroying old batteries, battery packs within an EV can occasionally be reused. Though rechargeable lithium-ion batteries will eventually lose their capacity to power an automobile, they can still be utilized for less intensive energy storage capacity, such as power backup (Wang and Guo 35). When a person replaces technology, such as an electric vehicle or a storage battery, reusing the old one is a bother. Alternatively, some manufacturers, such as Tesla, will collect and recycle their lithium-ion batteries after their useful life.

Yang, Fan, et al. “Impacts of Battery Degradation on State-Level Energy Consumption and GHG Emissions from Electric Vehicle Operation in the United States.” Procedia CIRP, vol. 80, 2019, pp. 530–535, Web.

Fan et al. state that lithium extraction produces greenhouse gases such as carbon (iv) oxide and may hurt the ecosystem. There is no proof to believe it will have a more significant influence than the one already produced by extracting gasoline from deep within the earth, processing it, and shipping it to gas terminals worldwide. There is no reason to think it will have a more significant impact than the one now being had by the deep-earth oil extraction, refining, and shipment to energy terminals worldwide.

After all this, just 20% of the fuel in gasoline was used (Yang et al. 530). When an accidental spill occurs, flowing oil has a terrible negative outcome on the environment. Sadly, millions of gallons are lost annually, putting many populations in peril. Treating crude oil — more particularly, heating it to 350 degrees Celsius—before it reaches gas stations results in significant emission of carbon gases (Yang et al. 532).

Yi, Zonggen, and Matthew Shirk. “Data-Driven Optimal Charging Decision Making for Connected and Automated Electric Vehicles: A Personal Usage Scenario.” Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, vol. 86, 2018, pp. 37–58, Web.

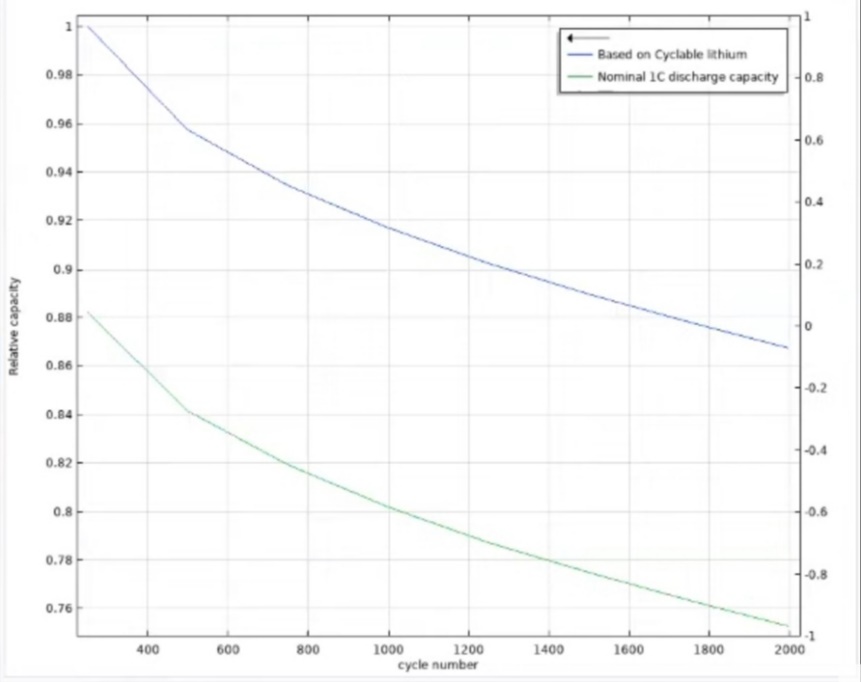

The scholars discuss electric vehicles powered by lithium cells, which produce a substantial amount of CO2 during production. The amount of CO2 emitted during the manufacture of a solitary cell with a 30 kWh (like the Petrol Car) or 900 kWh (like the Jaguar) range is 9230 kg and 8500 kg, correspondingly (Yi and Shirk 45). The released volume of CO2 is associated with discharge capacity, which is presented in Figure 4.

A lithium-ion battery comprises three crucial components: the cells, which contain the chemical constituents; the battery administration system; and the pack, which is the support structure for the cells. Since it has low weight, lithium is a crucial part of the system, but it also uses a lot of energy and contributes 17% of the device’s overall environmental impact (12.4 kg CO2/kWh) (Yi and Shirk 45). The cells contain the majority of the electricity and carbon dioxide that go into making a rechargeable cell.

Surprisingly, 40% of the battery’s entire climate impact is attributed to the mining, transformation, and refinement processes that produce the active components of cells (Yi and Shirk 45). These are Nickel, Magnesium, Cobalt (NCM), and lithium, which are then used to make cathode dust. The actual production of cells uses 20% of total energy and produces the second-highest quantity of CO2/kWh (14 kilograms CO2/kWh) (Yi and Shirk 45). Some energy-intensive cell manufacturing operations, including drying and warming, take place in large rooms where the quantity of electricity needed is consistent. Whether one or hundreds of units are being produced at a time, this statistic is highly dependent on the factory’s capacity.

Results & Discussion

During manufacturing, the emissions created by an electric vehicle are normally higher than those produced by a conventional vehicle. This is because lithium batteries, a perilous constituent of an electric car, are being manufactured. More than a third of the carbon (IV) oxide released from an electric vehicle is attributed to the energy cast-off in its production. As technology improves, this is improving for the better. Battery reuse and recycling are other growing industries.

Used battery study research techniques to repurpose batteries in technical advancements such as power storage. These options will aid in reducing the long-term environmental impact of battery manufacture. Undoubtedly, people should cease creating petrol/diesel automobiles if it is necessary to lower 80% of existing emissions by 2050 (DeMeuse 4). The advantages of driving electric vehicles in cities are immediate. They include less noise pollution and less air pollution, as well as the elimination of greenhouse gases and poisons such as nitrogen oxide. This is a chemical compound emitted by engines that are dangerous to air quality and people’s health.

Conclusion

In conclusion, lowering greenhouse emissions is important because it can impact the climate positively by reducing global warming. Most countries today are striving to reach the Net Zero philosophy. However, several factors have yet to make this possible in most countries. Even though the USA introduced electric vehicles that do not emit CO2 to combat the problem, the companies that manufacture lithium used in these cars have caused devastating effects on the environment and water supply. A solution to these problems could be recycling the lithium used in manufacturing the batteries to make electric vehicles a sustainable option.