European economic integration is a complex and ongoing process that is associated with both advantages and certain obstacles for European countries. To understand how economic integration is influencing the current members of the European Union (EU) and what changes in their economies can be predicted, it is necessary to analyze particular issues from microeconomic and macroeconomic perspectives. Hungary joined the European Union on 1 May 2004, and it is important to assess recent changes in its economic integration while presenting a forecast of future trends (Pintér, 2018). The purpose of this paper is to focus on the case of Hungary and analyze its labor market as a microeconomic issue and the question of its exchange rate regime as a macroeconomic issue.

Hungary and Its Experience with European Economic Integration

In the context of the European Union, economic integration means the unification of economic bodies and processes within this merged community in order to achieve conformity and potentially beneficial economic assimilation. These integration processes are possible with the guidance of specific EU policies that regulate economic relations in the union (Pintér, 2018). Hungary belongs to the Visegrád Group, which also includes the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Poland. All these countries were accepted to the European Union in 2004, but their paths toward economic integration have been different (Ivanová & Masárová, 2018; Pintér, 2018).

Within this group of countries, Hungary is less stable than its neighbors, and more attention should be paid to examining what factors influence its economic growth (Pintér, 2018). The current state of the Hungarian economy can be described as quite problematic because of periods of economic crises and damaging recessions that have influenced the country’s overall economic growth.

It is important to discuss the economic situation in Hungary after joining the European Union in comparison to the other three Visegrád countries. During the period of 2004 to 2006, Hungary had the second highest GDP per capita compared to the other Visegrád countries. However, the situation changed in 2007, and from 2007 to 2014, the Hungarian economy was in decline. This decline was observed in spite of the fact that “GDP per capita increased from €5000 in 2000 to €10,600 in 2014” (Ivanová & Masárová, 2018, p. 278).

Still, in comparison to the Czech Republic, Hungarian GDP per capita was only 72.11% of the GDP in the Czech Republic (Ivanová & Masárová, 2018; Pintér, 2018). As a result, currently, the highest rate of economic growth is found in the Czech Republic, Slovakia is second in this respect, and the situation in Hungary and Poland is almost equal.

Nevertheless, in comparing Hungary and Poland, it is important to note that the latter had no significant negative effects from the economic crisis of 2009 on its economy in comparison to Hungary. Therefore, since 2012, Poland has become more economically stable than Hungary (Ivanová & Masárová, 2018). In 2017, the total spending of the European Union in Hungary was €4.049 billion, and EU spending comprised 3.43% of the Hungarian gross national income was (“Hungary: Budgets and funding,” 2018).

Therefore it is necessary to examine what microeconomic and macroeconomic issues may be influencing the current development of Hungary in the context of European economic integration in contrast to the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Poland. The reason for focusing on the case of Hungary is the need to analyze how the country has coped with the barriers to its economic integration into the European Union. It is particularly important to discuss Hungary’s experience since 2014, when the country began to display its first economic achievements after a long period of decline.

The Microeconomic Issue: The Labor Market in Hungary

The purpose of this section is to present a discussion of the labor market in Hungary as the key microeconomic issue that is associated with the country’s integration into the European Union. This section includes a description of theoretical concepts in microeconomics that are related to the issue. An analysis of recent developments and the current situation regarding the labor market in Hungary is also provided, as well as a forecast of possible future trends in this area.

The Microeconomic Theory Background

The labor market in Hungary was selected for analysis as the critical microeconomic issue influencing economic integration into the European Union because the status of the markets and unemployment rates in the country indicate its economic stability. According to Baldwin and Wyplosz (2015), European integration has had the effect of promoting trade integration, leading to increasing local unemployment and intensified migration of employees, in the labor markets of the EU member states including Hungary.

Thus the trade integration typical of the European Union is associated with increased competition between European labor markets, and more flexible markets have become successful, creating higher demand for workers and attracting more employees. Another effect of European integration is associated with increased movement of workers within the EU countries (Baldwin & Wyplosz, 2015). In spite of fears that the workforce’s freedom of movement would lead to increasing unemployment rates in developed countries, the actual movement in Hungary has been minimal (Józsa & Vinogradov, 2017; Pintér, 2018). Still, this aspect should be taken into account when discussing the characteristics of the labor market in Hungary because it influences the labor supply.

Economic integration can influence labor markets whether they are flexible or inflexible, but the consequences for employers and employees are different. Inflexible markets are usually at risk of decreasing demand for workers because of losses firms experience in competition with other markets (Baldwin & Wyplosz, 2015). As a result, it is expected that through being involved in the economic integration processes of the European Union, labor markets will adapt to changes, as in the case of Hungary (International Monetary Fund, 2014).

It is necessary to examine the labor market in Hungary with reference to the following categories: the number of employed persons in the country, the unemployment rate, the employment rate, and the youth unemployment rate. These measures are important to consider when analyzing how the European integration process has affected the labor market of Hungary and what tendencies can currently be observed there.

The Current Situation Regarding the Labor Market

Currently, the labor market in Hungary is characterized by lower unemployment rates and higher employment rates in comparison to the rates observed in 2014-2016. Positive changes in the employment rates in the country’s labor market werfe first noted in 2017. From February to April 2017, the number of unemployed persons decreased by 1.3% in comparison to the data for 2016, and a continued gradual decline in the unemployment rate was observed after that (Ministry for National Economy, 2017).

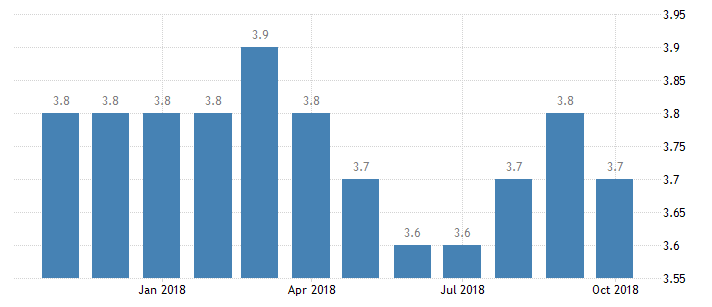

The Hungarian Central Statistical Office reported that the employment rate for the working population aged 15-64 years increased to 67.3%. Moreover, the unemployment rate for the working population aged 25-54 years declined by 1.1% (Figure 1; Ministry for National Economy, 2017).

The National Employment Service reported decreases in the number of registered jobseekers to 307,000 persons in comparison to the figures for 2016. From the perspective of the development of labor markets in other EU countries, in 2016, Hungary had an unemployment rate of 4.5% in comparison to the EU average of 8.2% (Ministry for National Economy, 2017). In contrast to the other EU countries from the Visegrád Group, it was a relatively positive result.

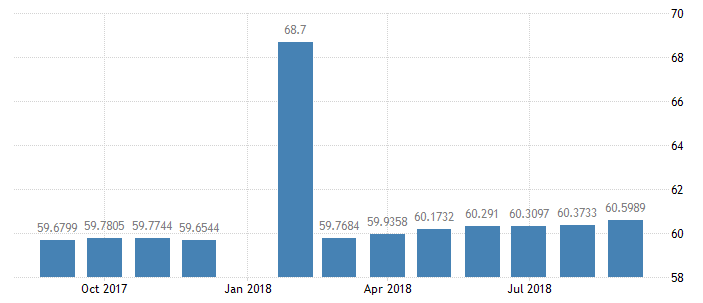

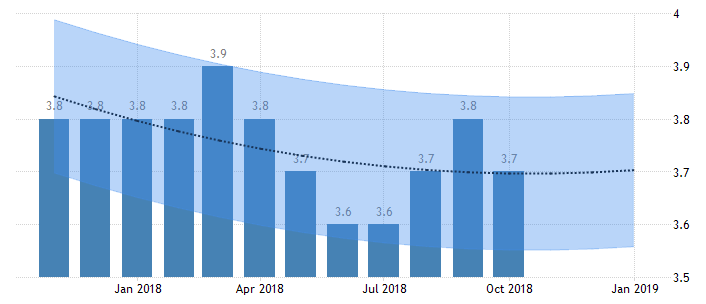

In 2018, the situation in the Hungarian labor market has remained advantageous for both employers and employees. The unemployment rate has declined to 3.7%, and the number of unemployed persons fell to 172,900 people (Figure 2). The current unemployment rate is the lowest it has been in the period of 1999 to the present, with an average rate of 7.42% (“Hungary: 2018 Data,” 2018). The employment rate reported for September 2018 was 60.6%, while the highest rate for the period of 2006-2018, 68.7%, was observed in February 2018 (Figure 3; “Hungary: 2018 Data,” 2018).

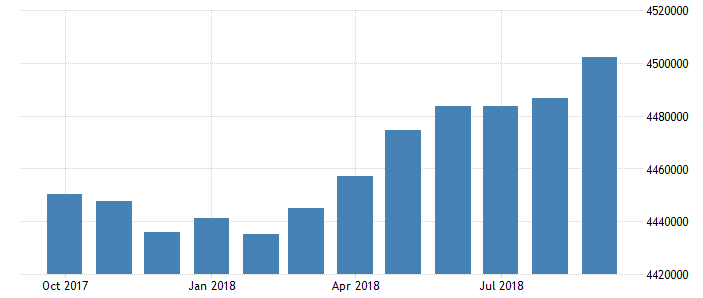

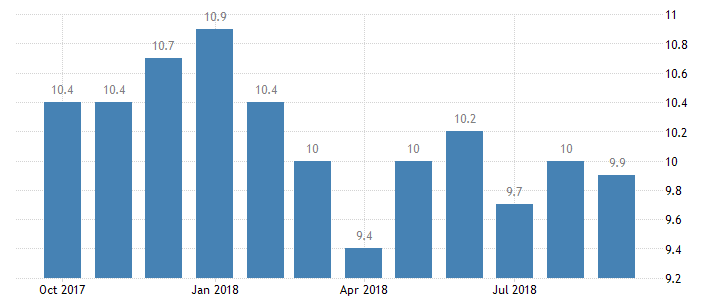

The number of employed people in the country also increased to 4,502,086 individuals in September 2018, which represents the highest number for the period of 1999 to the present (Figure 4). In this context, it is also important to note that, among the working population aged 15-24 years old, the unemployed rate, 10.5%, is relatively high (“Hungary: 2018 Data,” 2018). Still, the youth unemployment rate was reduced to 9.9% in comparison to the rate of 29.4% reported in September 2012 (Figure 5; “Hungary: 2018 Data,” 2018). These numbers demonstrate the current relative health of the Hungarian labor market.

All the tendencies observed in the labor market of Hungary can be associated with and explained by several economic factors that were influenced by European integration processes and related to national policies. Currently, Hungary is focused on achieving specific employment targets that were set in the context of the Europe 2020 strategy. According to this plan, the average employment rate for the EU countries should be 75% by 2020 (“Europe 2020 employment indicators,” 2018).

The current average employment rate for the EU nations is 72.2%, while the Hungarian employment rate is 60.6% (“Europe 2020 employment indicators,” 2018). As part of its commitment to following the Europe 2020 strategy and the European employment strategy, Hungary is focused on creating more jobs to increase demand and raise the employment rate.

The economic development and employment schemes that have been adopted, including the Territorial and Settlement Development Operational Program, are oriented toward promoting employment growth in coordination with EU institutions. Thus, in developing and implementing the National Reform Program, the Hungarian government followed the employment guidelines and targets set and adopted by the EU Council (Ministry for National Economy, 2017).

This aspect of European integration has positively affected the development of the Hungarian labor market. The reason for this measure can be found in the necessity of creating more jobs, retaining the youth, and building a competitive labor market in order to decrease the workforce’s movement.

The reformation of the Hungarian labor market in the context of the Europe 2020 strategy and European economic integration is also associated with other factors beyond employment rates that require attention. Increases in employment rates for different age categories are partially associated with the progress of the country’s private sector in the context of developing active trade relationships with other EU countries (International Monetary Fund, 2014).

Still, a more active growth of the private sector is recommended for Hungary. In addition, the public employment programs that have been implemented also had good results with respect to the creation of additional job positions.

The first significant reforms were enacted in 2011, according to the Széll Kálmán reform plan (International Monetary Fund, 2014). The economic changes that influenced the employment market in the context of this plan included the proposal of simplified business taxes, the implementation of changes in unemployment benefits, and support for options for flexible work hours. Additionally, the First Job Guarantee Program was implemented to support young jobseekers and reduce youth unemployment levels (International Monetary Fund, 2014). The minimum wage was increased on a national level, and the reform plan was fully implemented.

All the reforms and changes in the labor market of Hungary noted above have led to improving the key labor rates and measures. From the perspective of European economic integration, these results are associated with a focus on the Europe 2020 strategy objectives and making the Hungarian labor market more competitive and flexible. In addition, to address the risks of employees’ migration to other countries of the European Union, the Hungarian government focused on creating jobs in both the public and private sectors of the country (International Monetary Fund, 2014).

In spite of the positive trends that have been observed, there are still challenges that should be taken into account for creating a full picture of the Hungarian labor market. Hungary still suffers from low employment of low-skilled and young employees, as the youth unemployment rate remains relatively high. In addition, education and vocational training have still not been sufficiently reformed to affect the supply and demand imbalances associated with skill mismatches (Józsa & Vinogradov, 2017). As a result, many young persons are overqualified for the positions they are offered, and this creates additional barriers to employment.

Forecasts for the Future

In analyzing future changes in the Hungarian labor market, it is feasible to present a probable scenario for the next five to ten years. During the next five years, the situation in the labor market of Hungary will improve with a focus on achieving the Europe 2020 strategy goals and increasing the employment rate. If the Hungarian government is focused on developing private sector employment by supporting private companies and creating more jobs in this sector, the youth employment rate will also increase (International Monetary Fund, 2014).

To guarantee stable growth in employment rates for different age categories of the Hungarian population, it is necessary to continue the reformation of the tax system, which will affect employers’ choices (Józsa & Vinogradov, 2017). Furthermore, it is also necessary to reform the benefits system adopted by employers, which will affect employees’ choices of positions. The improved benefits and new policies for leaves and retirement plans will affect employment rates, increasing the supply of workers.

In ten years, the Hungarian labor market may be less stable than in five years because of the impact of potential economic crises, the intense migration of workers in the EU, and improved trade relations. One reason for the change is that the overall competitiveness of labor markets in the EU countries will increase at the same time they become more integrated (Pintér, 2018). Therefore, in view of the intensified economic integration processes, it is plausible to expect an outflow of employees from the Hungarian labor market (Józsa & Vinogradov, 2017).

These processes will become more likely if the problems of over-education, skill mismatches, and the absence of appropriate jobs for the youth are not resolved (International Monetary Fund, 2014). These factors should be addressed by the Hungarian government in order to prepare the country for more intense integration processes.

Moreover, it is also necessary to take note of the predictions made by specialists in the field of employment in the European Union. Current forecasts for the unemployment rate in Hungary indicate that it will increase to 4.5% in 12 months according to macro models and various analysts’ expectations (“Hungary: 2018 Data,” 2018). In 2020, this rate may rise to 5%, and, depending on the range of economic and social factors mentioned above, the rate may potentially rise even higher in ten years (Figure 6). Such forecasts are provided with reference to the analysis of the current labor market in Hungary and potential reforms associated with further economic integration into the EU.

The Macroeconomic Issue: The Exchange Rate Regime

This section presents information on the exchange rate regime, an important macroeconomic issue that is related to Hungarian integration into the European Union. This issue needs to be analyzed and discussed in detail in this report because Hungary is among the EU countries that still use their own currency for national financial operations. This section provides the macroeconomic theory necessary for a discussion of the issue and offers a description of the current situation in the country with reference to the most recent data relevant to the problem. Forecasts for the further development of this issue are also presented in this section in detail.

The Background Macroeconomic Theory

In the context of macroeconomic theory, the exchange rate question is discussed in connection with monetary policy and the mobility of capital. Exchange rate policies and regimes are formulated to emphasizing two of the following significant aspects: the autonomy of monetary policy, capital mobility, and fixed exchange rates (Baldwin & Wyplosz, 2015). Fixed and flexible regimes are the two basic types of exchange rate regimes that are determined with reference to their manipulation of monetary policy, capital, and rates. Fixed regimes are associated with pegged exchange rates, and flexible regimes are associated with various types of floating rates (Baldwin & Wyplosz, 2015).

In this context, free floating is associated with markets determining the exchange rate freely without the influence of monetary authorities (Hajnal, Molnár, & Várhegyi, 2015). The countries of the Eurozone who follow this variant of the exchange rate regime do so in order to focus on maintaining an autonomous monetary policy.

In turn, managed floating is associated with a “fear of floating,” and as a result, free floating exchange rates are managed by authorities. In the case of managed floating, reference to a fixed exchange rate is also avoided (Baldwin & Wyplosz, 2015). Thus it is possible to state that the European countries that rejected a pegged rate but did not adopt free floating exchange rates usually follow a policy of managed floating.

However, even if most EU countries choose floating rates, there are still debates regarding the strengths and weaknesses of these two types of exchange rate regimes. The advantages of fixed exchange rates are associated with higher credibility, lower inflation rates, and the creation of a stable economic environment with higher investment and active international trade (Bakker, 2017). Floating exchange rates are characterized by an economy’s flexibility and faster growth.

It is important to note that the countries of the Eurozone chose to emphasize autonomous monetary policy and full capital mobility in their exchange rate debates. However, other countries that joined the European Union without integrating into the euro area focused on the full capital mobility associated with a fixed exchange rate. These aspects influenced the choice of exchange rate regimes (Baldwin & Wyplosz, 2015).

Although the majority of EU countries have opted for exchange rate stability, there are still some countries in the union that have chosen monetary policy autonomy without depending on the euro. In the context of Hungary, it is important to focus on the two variants of floating: free floating and managed floating. There is not complete agreement regarding the regime currently followed in the country, which is often referred to simply as “floating” (Bakker, 2017). Furthermore, Hungary is currently among the countries which have not decided whether to adopt the euro instead of the local currency as a part of European economic integration. The nation is described as being on the path to adopting the euro in the near future.

The Current Situation Regarding the Exchange Rate Regime

According to the monetary authorities of Hungary, the country has chosen free floating for the forint exchange rate regime, and the euro should be described as a reference currency. This choice is a result of the country’s economic integration into Europe because, for a long period of time, Hungary followed a peg as the main exchange rate regime (Baldwin & Wyplosz, 2015). The situation of joining the European Union compelled the monetary authorities to revise their views regarding fixed exchange rates and floating in the context of using the national currency in Hungary (Stavárek & Miglietti, 2015). However, the problem is that, according to researchers and experts, floating in the country cannot be viewed as free, and the exchange rate regime adopted in Hungary is usually referred to as managed floating.

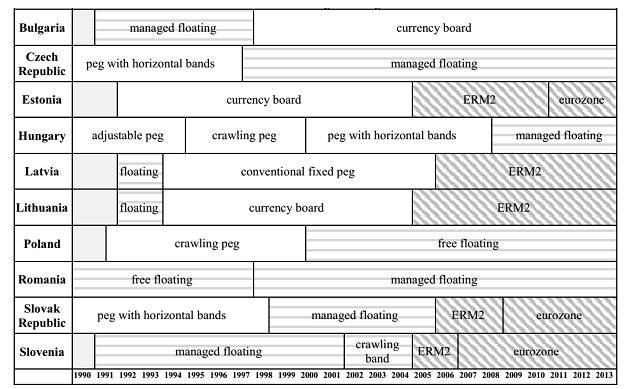

In order to understand the specifics of the current situation regarding the exchange rate regime, it is necessary to analyze the history of changing regimes in Hungary to determine the most appropriate one. In the early 1990s, Hungary used a pegged exchange rate regime that was dependent on the fluctuations in the exchange rates of foreign currencies Massoud & Horvath, 2015). The situation began to change in 1995 when the monetary authorities were oriented toward a crawling peg exchange rate regime, which was used until 2000. In 2000, Hungary chose a peg with horizontal bands. Furthermore, in 2001, “the central parity of the band was set at 276.10 then reduced in early June 2003 by 2.3%” (Massoud & Horvath, 2015, p. 32). Thus, a more flexible peg for the forint was adopted in relation to the euro.

These specific foreign exchange regimes allowed the country to enjoy the advantages of soft pegged regimes with a focus on very low levels of inflation. In February 2008, a floating exchange rate regime was adopted, but the actual form of the regime used in Hungary should be viewed as managed floating (Figure 7; Stavárek & Miglietti, 2015). Therefore, over a long period of time, the country tried to utilize specific semi-fixed exchange rate regimes in order to transition to managed floating.

The switch to floating was associated with an economic crisis in Hungary. The country’s authorities asked for international financial assistance and became focused on reforming the exchange rate regime in order to improve the economic situation in the country. As a result, the forint could depreciate without being defended by the central bank in order to avoid losing national reserves. For the period of 1998 to 2013, the currency of Hungary depreciated significantly, and by the end of 2013, the exchange rate value was weaker by 18.4% in comparison to the value in 1998 (Stavárek & Miglietti, 2015).

Thus, “the international lending program addressed these problems with a loan of €20 billion (including €12.5 billion from the IMF and €6.5 billion from the EU)” to the bank (Mabbett & Schelkle, 2015, p. 12). After the monetary crisis and implementing the transformation of monetary policy, Hungary finally adopted managed floating. This intermediate variant of the exchange rate regime allows Hungary to enjoy the benefits of both pegged and flexible regimes.

The monetary policy adopted in the Eurozone has a significant impact on those EU countries that have not adopted the euro because of the trade and financial connections that have developed between all EU nations. Furthermore, the monetary policy of the euro area has a considerable influence on Hungary because of its loans in the foreign currency (Massoud & Horvath, 2015; Stavárek & Miglietti, 2015).

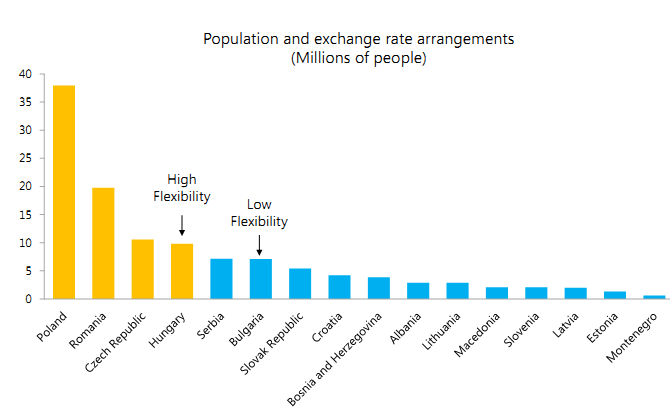

It is possible to state that the active integration of Hungary into the European Union allowed the country to develop its economic and financial potential through following a flexible exchange rate regime. This regime is most appropriate for countries as large as Hungary, and its benefits lie in making the economy more adaptable to crises (Figure 8). A high level of flexibility for Hungary is important to effectively adopt a free-floating regime, and positive results in this sphere are associated with the impact of European integration on the country’s economy.

Forecasts for the Future

Following the analysis of the current situation in Hungary with respect to the exchange rate regime and the use of the national currency, it is possible to predict the development of this issue over the next five to ten years. The most important factors that will influence the progress of this problem include the budget deficit, economic stability, and the inflation rate. If assuming a scenario that includes more thorough integration into the European Union, it is possible to predict that the country will join the Eurozone in about seven years. One reason for this schedule is the ongoing controversy regarding the necessity of adopting the euro in Hungary and the possibility of stabilizing the national economy in order to guarantee a successful integration.

If Hungary decides to join the Eurozone within the next five to seven years, it is possible to expect financial assistance from EU authorities, as was observed during the previous crisis period. It is important to note that currently Hungary “complies with three of the five convergence criteria for euro-area candidate countries” (Jóźwiak, 2017, p. 1). Thus, “inflation remains low (1.8%); the budget deficit is below 3% of GDP; the long-term interest rate criterion is also fulfilled (3.2%)” (Jóźwiak, 2017, p. 1). These criteria for adopting the euro are strictly followed, which makes it possible to speak of an opportunity for Hungary to join the Eurozone.

However, there are two other criteria that prevent Hungary from developing a workable plan for the country’s adoption of the euro in the near future. The government debt ratio is 74%, which is above the allowed reference value. Moreover, Hungary is not a member of the ERM II (Exchange Rate Mechanism), and this means that the country does not follow EU guidelines for the stabilization of the forint rate against the euro. To join the Eurozone, Hungary is required to follow the ERM II for two years (Jóźwiak, 2017; Mabbett & Schelkle, 2015). These aspects explain why Hungary cannot become a member of the Eurozone in the near future.

Furthermore, experts support the idea that rapid integration into the Eurozone cannot have a positive effect on the national economy because of threats to the country’s monetary policy. However, according to the data provided by the 2017 Eurobarometer, the public supports the adoption of the euro in the country (Jóźwiak, 2017; Massoud & Horvath, 2015). Thus, “the majority of residents (57%) supports the adoption of the single currency” (Jóźwiak, 2017, p. 2). Still, if Hungary adopts the euro in five to seven years, it is possible to expect that the country will shift to a free-floating exchange rate regime without using managed floating as a modified form of it.

However, a focus on free floating without monetary authorities’ control over exchange rates also bears some risks, including inflation and economic instability. Therefore, to address these risks in the future, it is important to guarantee that the Hungarian economy has been stabilized. In five to seven years, it is possible to expect that Hungary will improve its economy and increase its national income and competitiveness in order to implement the adoption of the euro (Jóźwiak, 2017).

Potential barriers are associated with the fact that GDP per capita in the country is lower than in other EU states. In this respect, “GDP per capita measured by purchasing power standard (PPS) was 67% of the EU average in 2016 (down by 1 percentage point in comparison to 2015)” (Jóźwiak, 2017, p. 2). During the next several years, the government of Hungary should concentrate on policies and reforms in order to stimulate the growth of GDP per capita. These measures can be regarded as the first important steps toward the improvement of the economic situation in the country in order to influence the development of the currency and improvement of the exchange rate regime in the future.

It can be assumed that, to shift from floating to free floating, Hungary needs to adopt the euro and focus on balancing its budget according to the examples that are followed by other EU countries. Thus the current floating practices used for the forint may not be effective enough because Hungary is at the stage of moving toward further European integration (Stavárek & Miglietti, 2015). As a result, a revision of the exchange rate regime can be expected in the future when the country joins the Eurozone. Therefore it is expected that the monetary authorities in Hungary will seek to avoid the fear of floating associated with increased foreign exchange volatility.

Conclusion

This report has presented an analysis of the labor market in Hungary as a microeconomic issue associated with the country’s economic integration into the European Union. Additionally, the report has provided a discussion of the exchange rate regime in the country as a macroeconomic issue that currently affects Hungarian integration into the union and will potentially influence the country’s development. The overall impact of European economic integration on the country can be viewed as positive and beneficial, and a more active merger can be predicted for the future.

It is possible to summarize the report with reference to the idea that Hungary is currently experiencing the active growth of its labor market in terms of positive employment rates for different age groups. This process can be associated with European economic integration because Hungary has adopted the principles of the Europe 2020 strategy and modified its labor policies according to it.

These changes, which were accompanied by successful national employment reforms, have led to decreasing the unemployment rate and increasing the number of employed persons in the country. Moreover, even labor migration processes in Hungary have not influenced the situation negatively. From this perspective, it is possible to state that European economic integration generally has a positive effect on the labor market in Hungary in spite of some weaknesses in the adopted reforms.

The acceptance of Hungary into the European Union has also influenced the exchange rate regime it has followed. Different European countries have various possibilities for applying a fixed regime or a flexible regime, depending on economic conditions, GDP, the national debt, and the size of the country. Hungary has experience with following a fixed exchange rate regime, but integration into the European Union has allowed the country to adopt a floating regime that is often viewed as more advantageous. In order for Hungary to complete its switch from a fixed regime or managed floating to free floating, the country’s authorities need to give more attention to the process of adopting the euro.

This process started some years ago, and it requires further stabilization of the country’s economy in order to achieve the desired results. Still, it is possible to predict the adoption of the euro in Hungary over the next five to seven years. In addition, the shift to a free-floating exchange rate regime can also be foreseen for this period of time, further integrating Hungary into the European economy.

References

Bakker, B. B. (2017). Exchange rate regimes in emerging Europe.

Baldwin, R., & Wyplosz, C. (2015). The economics of European integration (5th ed.). London, UK: McGraw-Hill.

Europe 2020 employment indicators. (2018).

Hajnal, M., Molnár, G., & Várhegyi, J. (2015). Exchange rate pass-through after the crisis: The Hungarian experience. MNB Occasional Papers, 121, 5-32.

Hungary: 2018 Data. (2018).

Hungary: Budgets and funding. (2018).

International Monetary Fund. (2014). Hungary 2014 Article IV consultation: IMF Country Report No. 14/156.

Ivanová, E., & Masárová, J. (2018). Performance evaluation of the Visegrad Group countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska istraživanja, 31(1), 270-289.

Józsa, I., & Vinogradov, S. A. (2017). Main motivation factors of Hungarian labor-migration in the European Union. Journal of Management, 31(2), 47-52.

Jóźwiak, V. (2017). Prospects of euro adoption in Hungary. PISM Bulletin, 97(1037), 1-4.

Mabbett, D., & Schelkle, W. (2015). What difference does Euro membership make to stabilization? The political economy of international monetary systems revisited. Review of International Political Economy, 22(3), 508-534.

Massoud, A., & Horvath, J. (2015). Exchange rate policy tensions: A comparative study between North Africa and Central & Eastern Europe. Applied Economics and Finance, 2(4), 25-35.

Ministry for National Economy. (2017). Lower unemployment and higher employment rates in Hungary. Web.

Pintér, T. (2018). The integration of Hungary into the European Union – Economic aspects. Civic Review, 14, 165-183.

Stavárek, D., & Miglietti, C. (2015). Effective exchange rates in Central and Eastern European countries: Cyclicality and relationship with macroeconomic fundamentals. Review of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 157-177.