Executive Summary

The Asian aviation market, albeit challenging, holds most of the potential for growth in the global aviation market. Comparatively, European airlines have been struggling to make a profit, even as they wade through the challenges of operating in a fragmented market and overcome the challenges brought by high operating costs and stagnating passenger numbers. This paper sought to find out the best market entry strategy for European low-cost airlines in the Asian aviation market. Three research questions, which sought to find out the factors that European low-cost airlines should consider when choosing a market entry strategy and explore the influence of trade agreements between Asia and Europe guided this review.

Through a mixed-method research study, and based on an investigation of the market entry strategies pursued by airlines around the world, this study reveals that there is no absolute answer to the best type of market entry strategy to use in Asia. However, we have found that firm-specific advantages and specific external success criteria influence the choice of market entry strategy for European low-cost airlines. Considering these dynamics, this paper proposes that the best market entry strategy to use in Asia is the strategic alliance option. Market limitations, strict regulations, and the lack of market uniformities in Asia are the main reasons for the selection of this strategy. The findings of this study will be instrumental in expanding the body of knowledge regarding global market entry strategies in the aviation sector.

Introduction

Background

The disappearance of Malaysian flight 370 and the recent crash of Metrojet flight 9268 highlight some of the challenges facing the global aviation sector. Coupled with financial turbulence and a rising cost of business, most airlines around the world are struggling to remain profitable (NDN, 2015). However, the Asian aviation sector is experiencing tremendous growth (Rimmer, 2014). Some observers believe it is among the only few markets in the world that have positive projections for growth, today (NDN, 2015). The positive economic growth in the Asian aviation sector is a product of market liberalization and a growing middle class (Rimmer, 2014). Low-cost airlines have driven this growth (NDN, 2015). Evidence of this trend has manifested in recurring pilot shortages and strained airport infrastructure in some Asian-Pacific countries (NDN, 2015).

Indeed, many Asian countries are struggling to upgrade their infrastructure to keep up with the growing demand for airline services (OAG Aviation, 2015). For example, big Southeast nations, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, are grappling with this challenge (Belobaba, Odoni & Barnhart, 2015). Other countries are also grappling with shortcomings in air traffic systems because of the rising numbers of air traffic in the region (Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2015). Observers, experts, and commentators in this sector say the Asian aviation industry is in “unchartered waters” because of the explosive growth that has characterized the market (NDN, 2015). Relative to this fact, one aviation consultant (cited in OAG Aviation, 2015) says, “I do not think the world has seen this sort of growth before” (p. 1).

Projections from the International Society of Transport Aircraft Trading show that the Asian aviation market is the largest global passenger market (Gössling & Upham, 2009). It has an annual growth rate of 4.9% (Belobaba et al., 2015). The Chinese and Indian aviation markets are leaders in this sector because they have reported growth rates of 10% and 11% respectively (OAG Aviation, 2015). Concisely, the Chinese and Indian aviation markets have the first and third largest airline passenger numbers in the world (OAG Aviation, 2015). Comparatively, the American aviation market has a growth rate of 3% (Centre for Aviation, 2015). The European aviation market also has similar growth numbers (Centre for Aviation, 2015). These figures show that the Asian aviation market has outperformed many of its peers. Its growth numbers are three times more than the same numbers reported in Europe and America. In this regard, it stands out as the center for aviation growth. Therefore, the growth of global airlines exists in their potential to tap into this trend. This is why this paper proposes a study to find out the potential market entry strategies that European low-cost airlines could use to venture into the growing and lucrative Asian aviation market.

Problem Statement

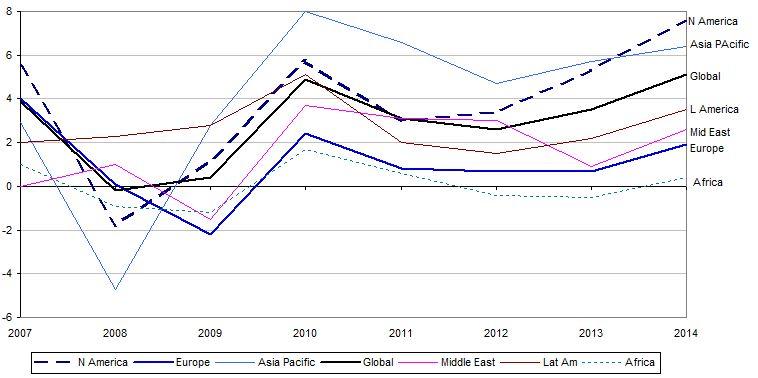

In the last decade, the European aviation sector has lost its competitiveness in the global aviation market (Minkova, 2011). According to a comparative analysis of regional aviation markets, undertaken by the Centre for Aviation (2015), the financial performance of many European airlines is poorer than its peers are. Albeit the performance of legacy airlines is worse than the financial performance of low-cost airlines, the general poor financial performance of many European airlines stems from structural and market challenges of flying in the European Union (E.U) (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012; Minkova, 2011). The relatively poor performance of European legacy and low-cost airlines explains why the European airline sector has produced the second-lowest earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) (Centre for Aviation, 2015). The graph below demonstrates this fact.

The end of the 2007 global financial crisis saw the North American and Asian Pacific markets emerge as the most lucrative global aviation centers (Centre for Aviation, 2015). Comparatively, European airlines have registered their worst global performance yet. The graph above demonstrates this fact. In this regard, they need to find new strategies for changing this trend. This paper proposes that they would do so by venturing into the Asian aviation market.

Justification for Study

For a long time, European airlines dominated the Euro-Asian route (Centre for Aviation, 2015). However, in the last decade, many Asian airlines, such as Emirates Airlines, Etihad Airways, and Qatar Airways have overtaken their European counterparts in this regard (OAG Aviation, 2015). This outcome has partly contributed to the dwindling fortunes of the European airline sector (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012). To reverse this trend, European airlines have to tap into the potential that exists in expanding their outreach beyond their primary markets. However, doing so is a difficult task because not all market entry strategies could provide positive results (Erramilli & Krishna, 1992). Therefore, there is a need to investigate the best market entry strategy that these airlines could use to venture into the growing Asian market (Harrison, 2009).

Research Aim and Questions

Aim

To find out the best market entry strategy that European Low-cost airlines should adopt when venturing into the Asian aviation market

Research Questions

- Are there barriers to entry for low-cost European airlines that wish to enter the Asian aviation market?

- What factors should European airlines consider when choosing a market entry strategy in Asia?

- What trade agreements could influence the type of market entry strategy in Asia?

Purpose of the Study

The findings of this study will be instrumental in expanding the body of knowledge regarding global market entry strategies in the aviation sector. For example, they would highlight the challenges and opportunities that exist for western (European) airlines to expand their outreach beyond their primary markets. This information would be useful in improving the decision-making processes of western-based airline companies, as they strive to select the best market entry strategy to use in the foreign market. Furthermore, they would understand the factors to consider when choosing a market entry strategy, instead of the trade agreements and barriers to trade that would define their operations. To answer the research questions, this paper would follow the following structure

Literature Review

Introduction

According to chapter one, this paper seeks to find out the best market entry strategy for European Low-cost airlines to use when venturing into the lucrative Asian aviation market. Guiding this investigation are three research questions, which strive to find out if there are barriers to entry for low-cost European airlines that wish to enter the Asian aviation market and the factors that European airlines should consider when choosing a market entry strategy in Asia. The last research question seeks to investigate if any trade agreements could influence the type of market entry strategy that European low-cost airlines could adopt when entering the Asian aviation market. These research questions outline the context of this literature review is investigating the research issue. Particularly, this chapter reviews the literature on international market entry strategies and the contextual factors that would affect the choice of market entry strategy for European airlines in Asia. Generally, it highlights what other researchers have said about the research topic.

Discussion

Trends in the Global Aviation Market

The global aviation sector has reported tremendous growth in the last two decades (Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2015). This observation stems from increased revenues, which have doubled in the last decade (Centre for Aviation, 2015). Referring to this growth, OAG Aviation (2015) points out that revenue in the global aviation market has increased from $369 billion in 2004 to $746 billion in 2014. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) claims that much of this growth stems from the increased dominance of low-cost airlines in the global aviation market (Centre for Aviation, 2015). These airlines now command 25% of the worldwide market (OAG Aviation, 2015). Developing markets account for most of the LCC’s growth. For example, low-cost airlines command 60% of Asia’s aviation market (OAG Aviation, 2015). Asian markets have shifted the global aviation landscape. Relative to this assertion, Price Waterhouse Coopers (2015) says, “The rapid growth of air travel in developing markets, such as Latin America and especially Asia, is shifting the industry’s centre of gravity to these regions” (p. 4).

Many observers have cited different reasons for the rapid rate of growth in the Asian aviation sector (Leeham News, 2015). However, the emergence of the middle class in Asia stands out as the main reason for this growth (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012). Particularly, the emergence of the middle class in China and India has driven this trend because, collectively, these two countries have a market of more than 2.7 billion people (Leeham News, 2015). This number is more than one-quarter of the global population.

Low-cost airlines have reported the highest growth numbers in Asia’s expansive airline market (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012). Airlines that operate in emerging economies, with the highest numbers of first-time fliers, have reported the highest growth numbers (Leeham News, 2015). However, Belobaba et al. (2015) say these airlines have also experienced significant challenges that stem from changing customer expectations and increased pressure to reduce operating costs and maximize efficiency. Most of them are in mature markets, such as Europe (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012).

This is why some of the main airlines in the continent have reported dismal performance compared to their counterparts around the world. However, Minkova (2011) says the poor performance of European airlines stems from overcapacity in some markets and excessive market fragmentation. Compared to their counterparts in the United States (U.S), American airlines have reported better economic performance because of bankruptcy restructuring and successful mergers and acquisitions (NDN, 2015). The redemption of European airlines stems from their quest to tap into the growing potential of the Asian airline market. Low-cost airlines are in a better place to exploit the market opportunities that exist in this market. However, before delving into details surrounding why these airlines are in a good position to do so, it is, first, important to understand the low-cost business model.

The Low-Cost Business Model

As shown in earlier sections of this study, the low-cost business model is emerging as a dominant force in the global airline market. According to conventional wisdom, low-cost airlines derive their competitive advantage from three interdependent sources- lower input costs, simplified products and services, and cheaper products and process designs (Hemphill, 2000). The success of the low-cost business model mainly depends on staff competency (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012). The employees do not necessarily have to be on-board staff because the ground and administrative personnel are also instrumental in making sure that the low-cost business model works (Doganis, 2001). Using cheap aircraft and servicing processes is also part of the low-cost strategy because they help to create cost savings for the airlines. Although such savings may accrue in different ways, they mostly emerge from lower nominal wages for employees, the acquisition of cheaper and older aircraft, and using underutilized or secondary airports (Clougherty, 2000).

While the low-cost business model has worked for many airlines in Asia and Europe, Bissessur and Alamdari (2008) fault its application because of its dependence on the availability of skilled personnel and the perennial reliance on idle and cheaper second-hand aircraft. The researchers believe that these factors are difficult to realize because of the constant volatility of the global airline market (Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). They also believe that the supply of underutilized airport facilities may decrease as low-cost airlines become more dominant in the global aviation market (Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). Also, Clougherty (2000) fails to buy into the idea that using older aircraft results in cost savings because these aircraft are less efficient than modern aircraft. For example, they use more fuel than modern aircraft do (Clougherty, 2000). Despite these conflicting views about the low-cost airline model, it still stands out as a dominant business model in the global airline market.

Low-cost Airlines in Asia

Few studies compare the operating model of low-cost airlines in Asia and Europe. However, many researchers agree that there are few differences between the low-cost-business model adopted in both regions (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012; Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). In Asia, low-cost carriers are mostly operational in large markets where passenger numbers are high. The table below shows the main low-cost carriers in specific Asian markets

Table 1: Low-Cost Airlines in Asia.

Low-cost Airlines in Europe

The low-cost airline industry in Europe started from the charter and tourism markets (Minkova, 2011). Albers and Heuermann (2009) say that more than one-fifth of low-cost airlines in Europe started before 1985. Again, most of the early adopters of the low-cost strategy emerged from the charter plane industry. For example, Air Berlin started this way (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). In the last two decades, Ryanair and Easyjet have carved a name for themselves as the two dominant low-cost airlines in the region (International Air Transport Association, 2009). From 2000 to 2006, there has been an increase in the number of low-cost airlines in Europe.

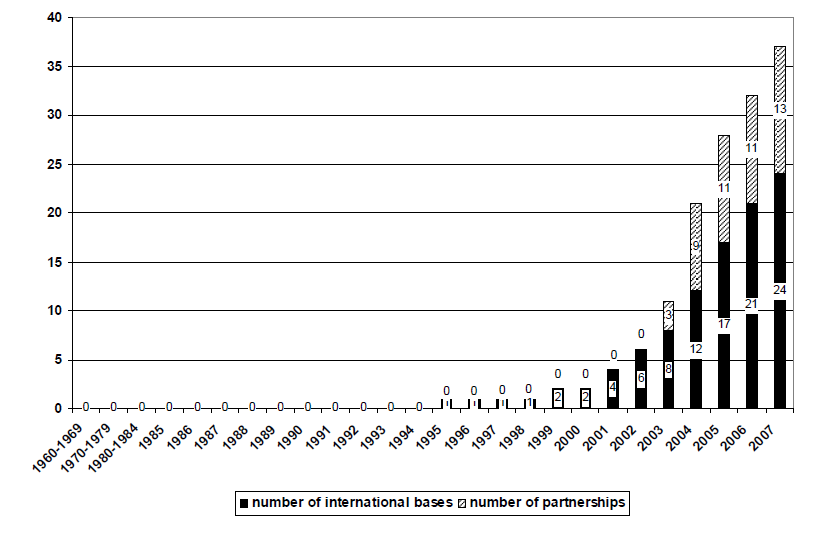

Flybe, Thomsonfly, and Sterling are some airlines that have rebranded during this period and created a name for them in the same way as Ryanair and Easyjet have (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). The proliferation of new low-cost carriers increased competition in the market and created the need for an internationalization strategy among existing airlines. This is why most of the dominant carriers started establishing foreign operation bases (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). Ryanair and Easyjet have been leaders in this regard. Following this trend, there has been an increase in the number of partnerships among these airlines, which have further increased the pressure to start new foreign bases (Minkova, 2011). Following this trend, in 2007, there were more than 13 alliances among low-cost airlines in Europe (Albers & Heuermann, 2009).

European low-cost carriers fall into three distinct categories, defined by their choice of market entry. Export is a common strategy in all the carriers (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). Stated differently all the carrier’s service markets outside of their home countries. A foreign direct investment (FDI) strategy is a rare market entry choice for most of these airlines (International Air Transport Association, 2009). These airlines also rarely establish new subsidiaries in foreign markets. The graph below shows the number of partnerships and FDIs pursued by these airlines in the last few years.

According to the diagram above, the volume of FDIs and partnerships among low-cost airlines in Europe only increased from 1995 (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). Before this year, there were few (or no) internationalization activities in the industry. Since 2001, the numbers of airlines that have set up operational bases in other parts of the world have increased (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). Therefore, FDI is the most common internationalization strategy in the market.

Modes of International Market Entry

Klug (2007) says the main motivation for international companies to enter foreign markets is to make profits cost-effectively. This section of the literature review shows the different types of strategies that these companies can use to achieve this goal. Numerous pieces of literature have shown that there are not less than five types and subtypes of market entry strategies. They include export, contractual agreements, joint ventures, and wholly-owned subsidiaries (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012; Albers & Heuermann, 2009; OAG Aviation, 2015). While these entry strategies cut across the product and service sectors, they differ based on their capital needs, control mechanisms, and their potential impacts on target foreign markets. Before delving into the details surrounding each market entry strategy, and how they apply to the context of this study, Klug (2007) says it is important to establish if an investor wants to invest equity in the target market before choosing an appropriate market entry strategy.

Equity investments refer to instances when an investor buys a company’s stock and controlling shares, while a non-equity stock refers to when an investor does not have a controlling stake (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012). This analysis is part of a hierarchical structure of analysis that should inform the decision concerning the best market entry strategy to choose. For non-equity modes of market entry, researchers agree that the best strategies to use are exports and contractual agreements (Peinado & Jose, 2006). Investors use joint ventures and wholly-owned subsidiaries in instances when investors want to buy equity in foreign market entries (Klug, 2007). Earlier sections of this literature review have shown that many European airlines use the export strategy to internationalize. This is a form of non-contractual agreement and it appears below

Non-Contractual Agreements

Export Strategy

Many researchers analyze the export strategy in terms of the production of goods and services from one location and transporting them to foreign markets (Peinado & Jose, 2006; Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012). This way, they imply that this strategy is mostly applicable to the manufacturing sector. However, airlines have used the same strategy in the service sector as well (International Air Transport Association, 2009). Its application in this field follows the same format as investors adopt in the manufacturing sector. Stated differently, an airline flies to multiple locations but maintains one operation base (usually in its home country). Therefore, it does not invest in the development of service centers in foreign markets. This advantage limits operation costs for investors. The strategy is most common in short-haul flights and commonly adopted by airlines that do not have a wide geographical outreach (International Air Transport Association, 2009).

Contractual Agreements

Albeit differing in terms of equity capital, investors often consider contractual agreements and joint ventures as cooperative forms of market entry in the airline sector (Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). Through mergers and acquisitions, these types of market entry strategies commonly emerge through partnerships in the airline sector. Companies that want to have more possibilities of control over their operations mostly use contractual agreements as the main market entry mode (Slack, 2010). There are different types of contractual agreements that could apply in the aviation sector. They include licensing, franchising, and alliances

Licensing

Following a definition by Hillstron (2015), a licensing agreement occurs when a licensor gives something of value to the licensee in exchange for certain performance standards or payments from the agreement. Depending on the nature of the licensing agreement, a company may be limited to implementing a contract in specific countries (Zekiri & Biljana, 2011). In return for the license agreement, the licensee may be required to market the licensed product, or service, in selected markets (Hillstron, 2015). Many researchers, such as Michael Porter (cited in Nielsen & Sabina, 2011), agree that a license agreement is most applicable when an international firm is unable to exploit a specific technology, or if it cannot adequately exploit a market if left to operate alone.

Licensing is a common strategy in the manufacturing sector, as opposed to the service sector. Although manufacturers find this strategy useful to their business, service-centered businesses also enjoy the same advantages, depending on the types of businesses they engage in (Nielsen & Sabina, 2011; Beyho, 2005). Based on its history of application in the airline sector, researchers agree that licensing is mostly applicable when airlines want to adopt new technologies (Zekiri & Biljana, 2011). They also agree that it is useful when airlines want to expand a brand franchise globally (Denton & Dennis, 2000). Similarly, it is applicable when airlines want to mold a global market image. In this regard, Klug (2007) says, instead of airlines entering new markets alone, they need to pursue licensing agreements to help them grow their markets quickly and to increase their dominance in the same regard.

Observers agree that this market entry strategy also allows companies to increase the popularity of their unlicensed products (Lai, 2012; Beyho, 2005). However, of importance is the understanding that licensing agreements need not necessarily be stand-alone strategies. They could merge with other approaches, such as strategic alliances, which are common in the airline industry (Beyho, 2005). Companies that choose to pursue this strategy stand the benefit of safeguarding their operational knowledge in-house (between associated firms), as opposed to diversifying the message to external firms (Zekiri & Biljana, 2011). Generally, licensing agreements contain provisions that make it difficult for companies to cancel their agreements in a short time (Zekiri & Biljana, 2011). By licensing other companies to produce their products or services, they need to make sure that they can trust their partners. Of concern is brand awareness because if the license agreement fails to achieve its goals, it may cause reputational damage to associated firms (Elango, 2005). Mostly, the licensor would suffer the highest risks because the public usually attributes such failures to them (Hillstron, 2015).

Franchising

Franchising shares a close relationship with licensing because they both include licensing business processes to a third party (Elango, 2005). However, this strategy differs from the licensing agreement because the franchisor has stronger control over the arrangement than a licensor who has little control over foreign operations (Ahmed, 2010). In this trade agreement, a franchisor runs an agreement under a franchisor’s trade name. In return, a franchisor benefits from such an agreement through fees and royalties. The most common types of franchise agreements are Coca-Cola and McDonald‘s. This type of trade agreement is mainly common in the US market, which is the leading franchise market, globally (Denton & Dennis, 2000). Franchising has become a common strategy in some aviation markets. For example, European airlines have commonly used it in their primary markets to safeguard their positions in the deregulated marketplace (Caves, 2007).

In Europe, British Airways is perhaps one of the earliest adopters of the franchising business model (Ahmed 2010). It adopted it in the early 1990s (Centre for Aviation, 2015). Since then, other major carriers have adopted it as well. Americans adopted this market entry strategy earlier than their European counterparts did because evidence shows that the earliest franchise agreements in the North American nation started in 1984 (Centre for Aviation, 2015). In Europe, franchising started because it was common for small airlines to operate on behalf of the national carrier (Caves, 2007). Therefore, the national carrier was the franchisor, while the smaller airlines were the franchise. Using the same arrangement, in the 1980s, British Caledonian had established a fleet of small airlines that operated under one banner (Klug, 2007). However, developments in the European airline market have changed the business model to adopt a complete type of franchising model (OAG Aviation, 2015). The adoption of the complete franchising model was a response by both small and large airlines to deregulation in the airline market (Graham, 1997).

Airline franchising, as is commonly practiced in Europe, involves one airline taking ownership of the public face of another airline (franchisor) (International Air Transport Association, 2009). The larger airline also takes ownership of intellectual property and know-how of small airlines (International Air Transport Association, 2009).

Commonly, airlines pursue the franchise strategy to improve their brand presence and free up slots at congested airports (a strategy for diversifying resources to more lucrative airline markets). In 1997, British Airways did so by stopping its services to London (Heathrow) -Inverness (OAG Aviation, 2015). The company benefitted from this action because it freed up three slot pairs daily for use in other activities.

Some possible risks of undertaking the franchise strategy include the risk of brand damage if the franchise fails (International Air Transport Association, 2009). The risk of accidents and excessive dependency are also real because researchers have found out that smaller aircraft, which participate in franchise agreements are highly prone to accidents and excessive dependency from large airlines that operate larger aircraft (Caves, 2007; Elango, 2005). Collectively, these insights show that it is important for airlines to evaluate their market needs and capabilities before using the franchise strategy as a market entry strategy.

Strategic Alliances

Strategic alliances are perhaps the most common market entry strategies in the airline industry (Centre for Aviation, 2015). Unlike franchise agreements, where there is a clear distinction between a franchisor and franchisee, strategic alliances involve undefined relationships among partners (Ahmed, 2010). However, most of these relationships consider competition as a major decision-making factor. Most strategic alliances are horizontal relationships among peers (O’Cass, 2012). These peers are airlines that often directly compete with one another. Nonetheless, strategic alliances may also be “vertical” to include relationships among firms that indirectly compete with one another (Caves, 2007; Elango, 2005). However, in the airline industry, most alliances are strategic and intended to achieve a specific goal, through a long-term agreement. To understand such a relationship, it is pertinent to explore one of the most notable alliances in the global airline market – The Star Alliance. The Star Alliance ropes in more than 18 airlines (Klug, 2007). However, Lufthansa and United Airlines lead this alliance.

The alliance started in 1997 and its members fly to more than 850 destinations around the world (Centre for Aviation, 2015). The Star Alliance aims to operate as one entity, especially from the customer’s point of view. The purpose of doing so is to offer customers a seamless travel experience (Bedi & Kharbanda, 2014). Therefore, its members share resources in different ways, including code sharing and common access to data (other platforms for sharing such information also exist) (Oum & Park, 2006). Most of the members of the Star Alliance benefit from the union because it allows them to expand their networks across the world, thereby making them more attractive to their customers (Klug, 2007). This advantage contrasts to a situation where each of its members operates alone because it would be difficult for them to overcome some of the political restrictions and financial challenges of operating internationally (Oum & Park, 2006). Similarly, the members know that it would be difficult to build the networks that the star alliance offers, single-handedly (Bedi & Kharbanda, 2014).

Political factors and market restrictions have made strategic alliances attractive to foreign airlines because they see this strategy as a step towards the liberalization of the global marketplace (International Air Transport Association, 2009). Although some strategic alliances in the airline industry may involve one company gaining some controlling shares over others, this is often not the primary goal for most airlines (International Air Transport Association, 2009). Usually, airlines that do so want to protect their investments.

Klug (2007) says there are two types of alliances in the airline industry – closing gap alliances and critical mass alliances. The closing gap alliance often occurs when airlines enter into strategic alliances to access resources that they would have otherwise been unable to obtain (Oum & Park, 2006). The critical mass alliance is common in markets where airlines have the same resources, but their collective power is inadequate to serve one market (Oum & Park, 2006). The Star Alliance is an example of such an alliance. Different airlines pursue strategic alliances for several reasons. However, improved customer service and customer satisfaction stand out as the greatest motivations for pursuing this strategy (Centre for Aviation, 2015). Higher flexibility and reduced risk are also other top reasons why airlines pursue this strategy (American Society of Association Executives, 2015). Enjoying economies of scale advantages and overcoming political restrictions are other motivations for pursuing this strategy. Without a strategic alliance, several markets would be out of reach for many airlines (American Society of Association Executives, 2015).

Joint Ventures

Joint ventures occur when two or more firms have shares in one company (Klug, 2007). Without inhibitive regulations, joint ventures should ideally have a 50:50 ownership between partners (American Society of Association Executives, 2015). Unlike most of the market entry strategies presented in this literature review, a joint venture requires airlines to have equity in an agreement. Experts who have investigated the success and failure of joint ventures say it is important for airlines to have synergies early in the agreement to enjoy the benefits of a joint venture strategy (Price Waterhouse Coopers, 2015). Since some governments have restrictions that require international companies to collaborate with local companies, as a foreign market entry strategy, many joint ventures develop for political rather than business reasons (Centre for Aviation, 2015). The opposite of a joint venture is a wholly-owned subsidiary (FDI). Wholly owned subsidiaries often involve establishing a new business in a foreign market. This type of venture has the highest capital investment and offers business partners the most control over a business (Centre for Aviation, 2015). This chapter has shown its popularity in the European low-cost market. Nonetheless, the choice of market entry strategy depends on different factors. Some of them are internal, while others are external. Barriers to entry are some external factors to consider.

Barriers to Entry

Predatory Behaviours

As the dominance of low-cost airlines continues to grow in the global aviation sector, observers are increasingly wary about the potential for predatory behavior by some of these airlines (OAG Aviation, 2015). It is important to review the contents of this argument because regulatory authorities in Asia who may perceive their entry as predatory could impede the entry of European airlines in the Asian market. However, to do so, they need to make sure that the entry of European airlines is indeed predatory. According to Bedi & Kharbanda (2014), regulatory bodies have a duty to establish whether predatory behaviors exist, as a matter of policy. To do so, regulatory authorities have developed tests and guidelines that would enable them to do so. A common test, highlighted as part of these guidelines, is comparing an airline’s pre-entry and post-entry revenues (Bedi & Kharbanda, 2014).

An assessment of an airline’s cost and capacity also allow regulatory bodies to know whether predatory behaviors exist, or not. Nonetheless, analyzing traditional aggregates of airline performance has been the traditional benchmark for studying airline behaviors (Doganis, 2001). In this regard, performance metrics, such as market revenues, average fare, and passenger traffic become useful indicators for analyzing airline performance (Doganis, 2001). However, according to the International Air Transport Association (2009), many regulatory authorities have ignored the impact of network passenger traffic and revenue management when evaluating whether airlines engage in predatory behaviors, or not. According to the International Air Transport Association (2009), predation in the airline industry is an unprofitable business and is unlikely to occur in regulated markets. Therefore, unless there are unusual market conditions, such as barriers to mergers and acquisitions, it is difficult to witness predatory practices in airline markets.

The literature on predation is plentiful. Some of the earliest literature on this topic emerged in the 1960s and 1970s through the game theory, which stated that predation could create a rational equilibrium in the market (NDN 2015). Erramilli and Krishna (1992) say the “long purse” assumption demonstrates this fact. Elango and Rakesh (2004) also say that the reputation model also highlights this fact. Although different researchers have highlighted different tests and guidelines for analyzing predatory behaviors, most of their studies have focused on evaluating revenues and cost advantages (International Air Transport Association, 2009).

Studies that have focused on highlighting the effects of predation in the airline industry have also analyzed the phenomenon in terms of its effect on passenger traffic and fares (American Society of Association Executives, 2015). Many of such studies highlight the effects of predation on competition and pricing; few of them focus on identifying and understanding the dynamics of the markets where these predatory practices occur (American Society of Association Executives, 2015). Furthermore, even fewer studies explore how these market dynamics affect competition in these markets. Besides predatory behaviors, trade agreements may also be barriers to trade for airlines. However, these agreements mainly depend on the nature of diplomatic relations between different countries. Nonetheless, many authors analyze these relations in terms of strategic alliances among airlines and in terms of different international aviation agreements governing global air traffic. This paper discusses most of these issues in subsequent chapters.

Summary and Implications

This literature review has shown that different factors relating to an airline’s internal and external environments affect international market entry strategies. In line with the research questions of this paper, this chapter has also shown that barriers to entry in international trade depend on understanding whether an airline’s market entry is predatory, or not. These factors would determine whether an airline chooses contractual or non-contractual market entry strategies. Comprehensively, the insights highlighted in this paper reveal that European airlines have to strike a careful balance between their internal competencies and the external (market forces). However, doing so requires a careful analysis of different contextual factors. Most of these issues emerge in the fourth chapter of this paper. The third chapter highlights the methodological framework of the study.

Methodological Framework

Introduction

According to chapter two, European airlines have to consider different contextual factors when choosing the best market entry strategy to use in Asia. Guiding this review were three research questions, which strived to find out if there were barriers to entry for low-cost European airlines that wish to enter the Asian aviation market and the factors that European airlines should consider when choosing a market entry strategy in Asia. These research questions outline the context of this chapter, as it reviews the modalities chosen to answer these research questions. Therefore, this paper outlines the research approach, research design, data collection methods, data analysis methods, and the ethical considerations in the study.

Research Approach

In this study, we used a mixed-method research approach to explore possible market entry strategies that European airlines could use to venture into the Asian aviation market. The mixed-method approach was appropriate for the analysis because the research issue included quantitative and qualitative aspects. For example, the research topic included quantitative factors that stem from the need for the market entry strategy to make economic sense to the European airlines. This analysis meant that the desired market entry strategy would include indicative statistics and other quantitative measures of analysis. The market entry strategy also has to consider the cultural and policy issues that govern international business between Asia and Europe. This is a qualitative issue. The mixed-method research approach accommodated these quantitative and qualitative issues because it overcame the limitations of using a single research approach (Greene 2007).

Research Design

According to Research Gate (2015), Given (2008) and Mertens (2009), the mixed methods approach has four major types of research designs – exploratory design, triangulation design, explanatory design, and embedded design. In this study, we used the exploratory design because we were not sure about which market strategy would be appropriate for European airlines to use when venturing into the Asian aviation market. This research design also allowed us to generalize our findings. This was a significant attraction to the study because its findings apply to the general European low-cost airline industry.

Data Collection

This study used information from secondary sources to come up with the research findings. Books and journals were the main sources of data collection. They came from reputable databases, such as Emerald Insight, Sage Publications, Google Scholar, and Springer. The research information also included articles from reputable websites. For example, it included information from government websites, government reports, and institutional databases.

Data Analysis

The data analysis process included the typology development technique. It develops unique, but related, sets of information categories for answering research questions (Caracelli & Greene, 1993). Many researchers have used this data analysis technique in human sciences (Caracelli & Greene, 1993). However, it is also applicable to the proposed study because researchers have used it to analyze data in descriptive mixed methods studies (Given, 2008).

Ethical Consideration

Some researchers believe that there are few (or no) ethical considerations in secondary research (Fielding & Fielding, 2003; Statement of Ethical Practice for the British Sociological Association, 2004). However, this is not the case because this type of research has ethical considerations that border on consent and privacy,

Consent

We used all the information in this paper after getting the authors’ consent. This permission is implicit because all the information used in this paper was available online. Furthermore, it was impractical to contact all authors and request their permission to use their contents. Nonetheless, we gave credit to all authors through proper citation.

Privacy

According to Prasad (2013), most issues surrounding secondary data analysis revolve around protecting individuals from harm. This issue manifests as a privacy concern for individuals. Most secondary data analyses differ in terms of the information available to identify participating parties. However, we coded the information used in this paper sufficiently to avoid this problem. Therefore, the data used was anonymous. We also kept all the data used in the paper safely, away from loss, or destruction because it was important to analyze the validity and reliability of the information used.

Based on the methodology adopted in this paper, we sampled numerous pieces of literature in this study to find out the best international market entry strategy that European airlines could use to venture into the lucrative Asian aviation market. Using the typology development technique, we reviewed more than 50 articles that explored international market entry strategies in the airline industry, with a bias on low-cost airlines. We also analyzed the potential internal and environmental dynamics that could affect the adoption of available market entry strategies for European airlines in Asia. The findings appear below

Findings and Discussion

Introduction

This chapter contains a reflection of the main findings of the study, in terms of its contribution to answering the research questions. Based on this analysis, this chapter investigated potential trade agreements that could influence the choice of entry strategy for European low-cost airlines in Asia and the possible barriers to entry that could impede the quest for European airlines to venture into the Asian aviation market. This chapter also contains information regarding the considerations for European airlines when choosing an appropriate market entry strategy. This chapter presents this information to address the research issue, which is to find out the best market entry strategy for European low-cost airlines in Asia.

Background

Chapters 1 and 2 showed that the Asian aviation market, albeit challenging, holds most of the potential for growth in the global aviation market. Comparatively, European airlines have been struggling to make a profit, even as they wade through the challenges of operating in a fragmented market, experience high operating costs and stagnating passenger numbers, coupled with increased competition (Civil Aviation Authority, 2005). Based on this background, this paper highlighted the need for these airlines to venture into the lucrative Asian aviation market. Although these airlines could redeem themselves by adopting this recommendation, few strategies could help them to do so. This is why this paper sought to investigate the best strategy that would suit European airlines as they venture into the Asian aviation market. Before embarking on this analysis, the following section of this report shows the most commonly used market entry strategies in the Asian aviation market.

Findings

Common Market Entry Strategies in Asia

Concerning the choice of international market entry strategies adopted in the Asian low-cost airline market, not much is happening because many low-cost airlines in Asia do not yet offer international services (Nielsen & Sabina, 2011). An assessment of this analysis reveals that many of the recently founded low-cost airlines fall within this category (Knorzer & Szodruch, 2012; Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). However, those that provide international services largely rely on export as the main market entry strategy (Nielsen & Sabina, 2011). In this study, 14 carriers fit this category. The analysis also includes different carriers from different nationalities. These differences highlight the limitations of internationalization in some Asian markets. This assessment also shows that most of the airlines that offer international services were subsidiaries of larger airlines. This finding points out to the possibility that low-cost airlines, which have the backing of larger and financially stable airlines are likely to internationalize more easily and effectively than airlines that adopt the strategy on their own. Contractual alliances and national subsidiaries are other international market entry strategies commonly adopted in the Asian aviation market. Many factors affect the choice to internationalize. Some of them appear below

Factors affecting Choice of Market Entry

Ownership

An extensive review of literature that has investigated international market entry strategies in the aviation industry reveals that the ownership structures of aviation firms affect their choice of market entry strategy (Brouthers, 1996; Chang & Ming-sung, 2009). In our review, we found that independent airlines, or publicly limited airlines, often pursue an aggressive internationalization strategy, but most of their strategic choices depend on their internal capabilities. Their internalized strategic options also depend on their FDI modes of market entry. Based on this understanding, most of these airlines often choose to adopt market entry strategies that give them complete, or majority, control over their international operations (Slack, 2010).

This is why such airlines often choose to acquire new companies, or start new operation bases in foreign markets, as suitable market entry strategies. Such strategies are not unique to legacy airlines, but also big low-cost airlines (Civil Aviation Authority, 2005). For example, some European low-cost airlines, such as Ryanair and Air Berlin have successfully pursued such strategies. Similarly, low-cost airlines that enjoy the dominance in their local markets also aggressively pursue such strategies. For example, Wizz and Vueling airlines have successfully adopted such strategies (International Air Transport Association, 2009). The choice of market entry strategy adopted by these airlines reveals that the financial advantage they enjoy from listing on the stock exchange gives them the power to choose “bold” market entry strategies. According to Chang and Ming-sung (2009), this financial advantage often allows such airlines to avoid contractual agreements, as possible market entry strategies.

Our study also revealed that most airlines, which operate as subsidiaries of the larger airlines, are likely to adopt international market entry strategies that fit their strategic choices (Civil Aviation Authority, 2005). This is why they mostly prefer to choose contracts-based market entry strategies. Such airlines are often vulnerable to hostile takeovers, or acquisitions (International Air Transport Association, 2009). Their decision-making processes are also slow (Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). Similarly, they do not have an independent strategic outlook because their aims and objectives have to reflect the vision of the parent company. Based on these insights, this study advances two propositions. The first one states that independent and public limited airlines prefer internalized market entry modes. The second proposition demonstrates that low-cost airlines, which are tied to larger airlines (in terms of ownership), prefer contract-based market entry strategies.

Leadership Style

From a speculative perspective, the findings of this study also reveal that leadership styles affect the choice of market entry strategies that European airlines could use when venturing into a foreign market. This view stems from the power of strong leadership on some of the major airlines in Europe. Stated differently, the success of some of these airlines stems from personal competence or leadership styles. For example, the successes of Air Berlin and Ryanair have depended on the leadership styles of their chief executive officers (CEOs) Joachim Hunold and Michael O’Leary (Nielsen & Sabina, 2011). According to Proussaloglou & Koppelman (2009), extroverts and people with strong personalities, who often choose bold strategies when undertaking their international operations, head these airlines. Evidence also shows that such leaders prefer to choose international marketing strategies that give them the most autonomy to their businesses (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). However, this phenomenon is not unique to European airlines because our analysis reveals that some Asian airlines are also dependent on the strong leadership styles of their CEOs. For example, the success of AirAsia has traditionally depended on the leadership style of Tony Fernandez (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). Collectively, this analysis reveals that internal company dynamics have a role to play in selecting the best market entry strategy.

Operational Issues

A review of extensive literature sampled in this paper revealed that many European airlines were concerned about the impact of internationalization on their operations (Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). They are mostly concerned about the potential for quality and process controls when choosing their international market entry strategies (Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). The most internalized market entry modes often address these concerns because they give foreign markets direct control of their operations and processes. Within such strategies, airlines only duplicate their service and processes in the foreign markets (OAG Aviation, 2015).

In such situations, the airline maintains all its processes within the organization to prevent them from dilution. This way, they minimize the risk of quality problems and slack by limiting the involvement of third parties. However, according to the International Air Transport Association (2009), this route does not have to be the norm because quality control can occur through modes of cooperation among partners. For example, through codification, partners can maintain high-quality standards by agreeing to a set of standards and specifying the same in a contract (American Society of Association Executives, 2015). Similarly, partners could agree that foreign players could minimize the risk of plagiarism or unwarranted technology transfers through majority equity ownership (American Society of Association Executives, 2015).

Cooperation-based Strategies

According to Proussaloglou and Koppelman (2009), the airline industry witnessed a significant reduction in the importance of cooperation-based strategies from 2005-2007. However, its importance in the Euro-Asia market has not declined because of the relatively high risks associated with operating in Asia. Despite the huge capital cost associated with venturing into the Asian market, researchers also agree that time is an important consideration for the pursuance of a market entry strategy in Asia (American Society of Association Executives, 2015).

Chen and Jing-Yun (2011) say when forging contractual agreements among airlines, older airlines have first-mover advantages over their relatively new counterparts. Since European low-cost airlines are relatively older than their Asian counterparts are, they are likely to enjoy this advantage when forging contractual relationships. However, recent research reveals that new low-cost airlines could suffer from marginalization because of their relatively new entry in the market. However, in response, researchers, such as Proussaloglou & Koppelman (2009), reveal that these new low-cost airlines have learned to develop a competitive advantage by developing economies of scale over their relatively older counterparts. In this regard, they can strengthen their market positions and financial advantage over their competitors.

Cooperation-based strategies make it easy for foreign companies to enter into international markets easily by collaborating with a partner who already operates in the target market (Proussaloglou & Koppelman, 2009). This strategy gives them a strong market presence in their selected markets. Many kinds of literature that sampled the choice of cooperation-based strategies among low-cost airlines in new markets say their choice of market entry strategies are reactions to the first-mover advantages enjoyed by older low-cost airlines (Chen & Jing-Yun, 2011).

Some researchers also believe that their choice of market entry strategy is a reaction to market developments in the low-cost airline market. According to Vowles (2009), low-cost airlines that intend to compete with older low-cost airlines can do so by adopting less internalized market entry modes. Vander & Stephen (2000) second this view by saying it is the only way such airlines can claim first-mover advantages (the advantages enjoyed by older low-cost airlines); otherwise, they would have to settle for second-mover advantages. Based on a cumulative assessment of these observations, we find that cooperative market entry modes are mostly appropriate for low-cost airlines that want to gain first-mover advantages, while new low-cost airlines need to adopt cooperative market entry strategies if they want to build a strong international network, fast (all factors constant).

Trade Agreements that could Facilitate or Impede Market Entry

Deregulation has characterized the global airline market in the last decade (Graham, 1997). However, this trend has been intense lobbying among major airline carriers to create strategic alliances to ease the burden of operating in the global airline market. However, most of these alliances involve legacy airlines and those that offer long-haul flights. Low-cost carriers have not reached this level of collaboration because they mostly operate in regional markets (International Air Transport Association, 2009). However, they benefit from international trade agreements between countries. This paper demonstrates that few trade agreements between Asia and Europe could affect the type of strategy that European low-cost airlines could adopt in the Asian market.

Nonetheless, regional trade agreements among Asian low-cost carriers make it difficult for European airlines to overcome the competitive advantage created by such agreements. This paper has paid attention to the Association of Southeast Nations (ASEAN) agreement as to the single-most formidable trade agreement that could affect the choice of market entry strategy for European low-cost airlines (International Air Transport Association, 2009). Since its introduction, members enjoy a strong competitive advantage that its rivals cannot replicate in a short time. For example, they enjoy a strong infrastructural and network support that other airlines cannot replicate with limited resources (International Air Transport Association, 2009). Based on this fact, it would be difficult for European airlines to compete with their Asian counterparts without collaborating with local airlines.

Besides the ASEAN agreement, it is also important to note that airlines that fly across the Europe-Asia route often enjoy an open-skies policy that promotes increased competition, lower fares, and increased numbers of flights (International Air Transport Association, 2009). Within this arrangement, concerned parties enjoy the liberalization of rules and regulations that govern the international aviation industry. The aim of doing so is to create a free-market environment for both Asian and European airlines. Based on this understanding, one primary objective of the open-skies policy between many Asian countries and European airlines is to liberalize the rules of international aviation and minimize government influence that could affect aviation processes (International Air Transport Association, 2009).

Another objective of the open-skies policy is to adjust the regime under which states may allow military and other state-based airline flights to carry on with their operations without any restrictions. Nonetheless, compared to other types of open-skies policies between Europe and other countries, many Asian markets remain relatively more regulated than other parts of the world (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). Despite this environment, many Asian airlines continue to compete with European airlines favorably. In response, some legacy airlines in Europe have lobbied against the open-skies agreement, citing unfair competition from fast-growing Asian airlines, such as Emirates and Qatar airways that receive immense government subsidies (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). However, they have not changed the status quo.

Discussion

Factors European Airlines Should Consider When Choosing the Market Entry Strategy

Based on an investigation of the market entry strategies pursued by airlines around the world, there is no absolute answer to the best type of market entry strategy to use. However, this paper has found that firm-specific advantages and specific external success criteria influence the choice of market entry strategy to use (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). Particularly, the political, social, and economic environment in the host nation has the strongest influence on the selection of the best market entry strategy to use in the Asian market (Goel, 2015). For example, if there are few restrictions and a stable market in the host market, European airlines may prefer to establish wholly-owned subsidiaries as the best market entry strategy. However, if the host market does not have a liberal market structure or a stable market, it would be difficult to adopt a market entry structure that premises on introducing new wholly-owned subsidiaries. Instead, the European airlines may be better off choosing cooperative agreements with local airlines.

The findings of this paper show that the Asian aviation market is relatively less liberal than the European aviation market (O’Cass, 2012). Therefore, European airlines should pursue contractual agreements with existing Asian airlines as the best market entry strategy to venture into the Asian aviation market. This strategy is appropriate for European airlines because it has a proven record of working in relatively regulated markets (International Air Transport Association, 2009). Furthermore, it complements the strict legal requirements that exist in some Asian markets, which require foreign airlines to collaborate with local ones if they intend to operate in their markets (American Society of Association Executives 2015). These legal requirements are most common in Middle East countries, which require majority local ownership in multinational enterprises (American Society of Association Executives, 2015).

Pursuing a strategic alliance in Asia would also improve the probability of success for European low-cost airlines in this market because, globally, airlines have gained a lot of knowledge regarding its success and failure in the aviation market (American Society of Association Executives, 2015). Therefore, they do not have to repeat the same mistakes that other airlines have made when adopting this strategy. The presence of a reference point to pursue the strategic alliance option will also be instrumental for the European airlines to distinguish between convenient and strategic alliances. Goel (2015) says that this process depends on the airlines’ competence in understanding the key criteria for strategic alliances. These key criteria include an acknowledgment of the following factors:

- The strategic alliance should be critical to the success of the core business

- The strategic alliance should be critical to the development, or improvement, of the business’s core competence

- The strategic alliance should minimize competition

- The strategic alliance should create or maintain, strategic alternatives for the European airlines

- The strategic alliance should mitigate significant risks associated with European airlines venturing into the Asian market.

By acknowledging these facts, European low-cost airlines would easily identify the best strategic alliance to use, based on whether they represent strategic, or convenient, market entry strategies.

Adopting the strategic alliance option would also help European airlines to navigate some of the operational challenges of operating in a diverse, relatively reserved, and multicultural Asian market (Goel, 2015). For example, by seeking strategic alliances with local partners, the European companies would enjoy the benefit of having local contacts, language capabilities, and understanding local business styles in Asia (Goel, 2015). These competencies would help it improve its operational efficiencies in the market. Relative to these advantages, Oum & Park (2006) add that European airlines should pursue strategic alliances as the best form of the contractual agreement for the airlines because they require limited investments and have minimal risks. The pursuant of the strategic alliance option supports a narrative by Goel (2015), which stated, “to be part of an alliance will become a necessity for an airline to survive in the future” (p. 2).

Why other Strategic Options are Unfavourable

Under the banner of contractual agreements, this paper identified licensing, franchising, and joint ventures as other strategic options that airlines could use to enter new markets (Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). However, these options are less desirable to the strategic alliance model because of several reasons. For example, franchising is the wrong strategy to use in Asia because it is often successful in highly deregulated markets (Elango & Rakesh, 2004). This is why this paper shows its tremendous success in American and European aviation markets because of its relatively high levels of deregulation (Graham, 1997). Since this study reveals that the Asian aviation market is highly regulated, relative to European and American aviation markets, the franchising business model would have a relatively low level of success compared to strategic alliances.

The literature sampled in this paper also revealed that licensing is not a sound business strategy to use in the Europe-Asia market because it is widely unpopular in the aviation market (International Air Transport Association, 2009). Its popularity emerges in the manufacturing sector where international companies license foreign subsidiaries to manufacture goods on their behalf (Klug, 2007). Therefore, its application in the service industry is relatively limited because it is difficult to standardize the level of services offered in different countries, relative to varying customer expectations, changes in customer preferences, and varying cultures. In this regard, European airlines may lose control of their business and market competencies. Furthermore, the literature sampled in this paper reveals that this market entry strategy is less profitable than other forms of market entry strategies highlighted in this paper (Elango & Rakesh, 2004). The acquisition would have been a good alternative strategy for the European airlines to use in the Asian market, but market restrictions on foreign ownership of local firms prevent its successful adoption (Bissessur & Alamdari, 2008). These factors, among a myriad of other challenges, prevent the successful adoption of alternative market entry strategies for European low-cost airlines in Europe. Some of the barriers to entry appear below.

Barriers to Entry

Lack of Market Uniformity

This paper has reviewed several pieces of literature that have highlighted different social, political, and economic factors for entry into the Asian market. These insights reveal that Asia is not a homogenous market where the same rules apply in all markets. Different legal, social, and political factors affect how these markets react to foreign entry strategies. For example, the Association of Southeast Asia Nations (ASEAN) influences the Asian aviation market (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). Similarly, this paper has shown that Asia has different regional and sub-regional markets with varying social, political, and economic factors. For example, there are marked differences between the Middle East and the Asian-Pacific markets (Albers & Heuermann, 2009). Most of the low-cost airlines highlighted in the literature review appear confined to the Asian-pacific region.

The Middle East has many large carriers such as Emirates Airlines and Qatar Airlines that mostly compete with legacy airlines in Europe. This analysis alone shows that the Asian-pacific region is more concentrated, at least in terms of the activities of low-cost airlines, compared to Middle East markets. Considering the varying market dynamics across the vast Asian market, it is pertinent to highlight this fact, as one barrier to entry for European low-cost airlines that intend to venture into the Asian market. Indeed, it is difficult for European companies to tailor one strategy that would work in the different regions and sub-regions of the Asian market. This would mean that the companies have to develop different market entry strategies for the different regions to make a profit. Such a strategy would not only be time-consuming, but costly as well. Furthermore, it would beat the purpose of venturing into the Asian market in the first place because the market’s lucrative nature stems from its consolidative nature. Therefore, dividing it into small divisions with unique social, political, and economic dynamics would make it unprofitable and unattractive to European firms.

Strict Regulations

This paper has already shown that the Asian aviation market is relatively more restricted to foreign companies compared to the European market. These limitations have a strong impact on the choice of market entry strategy that European airlines could use in Asia. For example, restrictions on disclosure of financial records and relationship restrictions limit the choice of market entry strategies that European airlines could adopt in the Asian aviation market. Lauer (2015) says that, recently, some Asian countries introduced new restrictions on franchise agreements in the aviation market that limit the choice of market entry strategies in this region. These legislations have put an additional burden on franchisors. For example, some major Asian markets have imposed restrictions on who can participate in franchise agreements with partners in their countries.

China has such a restriction (Lauer, 2015). It stipulates that a potential franchisor should have operated two units in the country before it receives approval to undertake its activities in the communist nation. Many researchers know this requirement as the “2/1 regulation” (Lauer, 2015, p. 4). In 2007, the government crumbled under intense criticism from observers who believed this law was punitive. In response, the country further changed this law to include out-of-the-border activities, but observers still deem it insufficient to attract enough foreign players in the market (American Society of Association Executives, 2015). Vietnam also has a similarly restrictive law on foreign players because it requires them to contract local entities that have operated for more than one year. They also demand that the types of services offered by foreign airlines should align with Vietnamese standards (Lauer, 2015).

The presence of restrictive disclosure laws in some Asian countries also limits the number of market entry strategies that European airlines could use in Asia. For example, foreign entities that want to enter or leave a market have to comply with complex disclosure requirements. In 2008 and 2007, Korea and Vietnam introduced such laws, respectively (International Air Transport Association, 2009). For example, Korea has an elaborate pre-sale registration requirement for all foreign entities. Therefore, foreign airlines that want to adopt a franchise strategy also have to produce a pre-sale franchisor registration requirement and a franchise disclosure agreement (American Society of Association Executives, 2015).

These restrictive laws also affect when and how foreign market entities choose to exit the market. For example, China requires foreign companies to register with the government within 15 days after both partners in a contractual agreement choose to terminate their operations (Lauer, 2015). Indonesia also has a similar law because, in 2009, the government introduced new laws that require foreign entities to produce disclosure documents and other materials used in a contractual agreement before exiting the market (Lauer, 2015). Japan also has similar, but multiple, laws that foreign entities need to comply with, depending on the type of market entry strategy they choose (Lauer, 2015). Taiwan has a law that requires foreign companies to disclose their financial documents before exiting the market. Malaysia has a thorough vetting process for proposed contractual agreements (Ahmed, 2010). Sometimes, this process is lengthy and costly to foreign companies.

Relationship laws in some Asian countries also emerge as barriers to entry in these markets. For example, many Asian countries have laws that govern contractual relationships between foreign and local firms. In 2008, Korea introduced a new law that governed the relationship between local and foreign firms by introducing specifics of the type of contractual obligations that the two parties may have (Lauer, 2015). These specifics are a prerequisite to the transfer, termination, and renewal of contractual arrangements between local and foreign firms. The Philippines has a similar law that imposes restrictions on international trade through competition laws, transfer restrictions, and renewal laws (Ahmed, 2010).

Restrictions on local ownership also have the same impact on European airlines that want to venture into Asia, as relationship laws in Asia do because they limit the options for foreign market entry. Particularly, they have a strong impact on the potential for foreign companies to venture into Asian markets through contractual agreements that involve foreign-local partnerships. Lauer (2015) says that many Asian countries restrict the extent of foreign ownership in local countries. This restriction limits the pool of companies that foreign airlines could collaborate with when venturing into the Asian market. The Philippines has such a law (Ahmed, 2010). Other countries, such as Vietnam also have such laws, but restrict them to certain industries, which are vital to their economies (Ahmed, 2010).

For example, Vietnam limits foreign participation in the catering and hotel business. Comprehensively, these insights reveal that although the Asian aviation market is a lucrative one for European airlines, they need to consider the effect of market restrictions on the choice of their market entry strategies. This way, they can better plan the effect of time, cost, and effort when choosing the best market entry strategy. Nonetheless, according to Lauer (2015), the restrictions characterizing the Asian aviation market are not supposed to stop European low-cost airlines from venturing into the market. Many established European carriers have ventured into this market, successfully, regardless of the strict regulations. Therefore, despite the restrictions on foreign entry strategies, this paper does not negate the potential, or suitability, of the Asian aviation market for European low-cost airlines. Furthermore, considering some European low-cost airlines are affiliated with larger airlines, which enjoy vast knowledge in internationalization, they could receive immense support in their quest to venture into the Asian aviation market.

Summary

Based on an assessment of this chapter’s finding, we deduce that the strategic alliance option is the most appropriate strategy for European low-cost airlines to use in Asia. Market limitations, strict regulations, and the lack of market uniformities are the main reasons for the selection of this strategy. While it is important to exploit market opportunities provided by the open-skies agreement, European airlines should also be careful to wade through market consolidation efforts ongoing in the Asian market.

Conclusion

Introduction

This chapter is a summary of the main findings of this paper. It provides a critical review of the research findings for purposes of developing recommendations and reviewing the importance of the findings to the understanding of market entry strategies in the aviation sector.

Critical Review

This paper sought to find out the best market entry strategy for European low-cost airlines to venture into the Asian aviation market. Three research questions, which sought to find out the factors that European low-cost airlines should consider when choosing a market entry strategy and strived to understand the influence of trade agreements between Asia and Europe, which could affect the choice of market entry strategy, guided this review. This paper also sought to find out possible barriers to the entry of European low-cost airlines in the Asian aviation market. The sections focusing on trade agreements between Asia and Europe revealed that Asian aviation markets are following the trend of market consolidation that Europe has undergone (Graham, 1997). The formation of the ASEAN block is a testament to this fact because it is an attempt by leading aviation markets in the region to integrate their markets.

Considering that, European airlines have to think of different factors when choosing the best market entry strategy in Asia, this paper categorizes their choice into two factions – internal and external factors. The internal factors appeared in chapter five of this paper. They refer to leadership styles, financial capabilities, firm size, and ownership structures. External factors include market size, country risk, and legal restrictions. This paper has analyzed these two spheres of influencing factors to identify the strategic alliance option as the best market entry strategy for European airlines in Asia. This contractual strategy could help the airlines to build a strong market presence in the region, faster than they would have done so if they adopted a different strategy. However, this market entry mode is still subject to internal company dynamics for individual airlines. Therefore, their resources, skills, and capabilities would play an instrumental role in identifying the best type of contract-based strategy to use in the market. The evidence provided in this report has revealed that low-cost airlines, which are attached or associated, with larger airlines are better off choosing these equity-based strategies because it gives them more control and ownership of their international operations. Thus, we can deduce the fact that the best market entry strategies for European airlines in Asia depend on the balance between external and internal forces.

Key Insights

Based on an assessment of the literature sampled in this paper, we find that the internationalization process of low-cost airlines is a relatively underdeveloped area of research. This paper sought to develop this field by providing insights regarding the possible internationalization process of European low-cost airlines in Asia. In this regard, it provided a content-specific understanding of internationalization in the low-cost market. From a theoretical and international management perspective, the insights highlighted in this paper contribute to the growing body of literature regarding internationalization in the low-cost airline market. Another key insight we have found out in this study is the relevance of ownership and control in choosing the most appropriate market entry strategy.

Details of this analysis have revealed that FDI and export are the most desirable international market entry strategies because of the control and ownership they give to participating airlines. This paper has also shown that the choice of the internationalization strategy depends on an airline’s calculus of competitive advantages, which it intends to leverage in foreign markets. Their financial resources, leadership styles, and organizational structures also play a vital role in their choice of international strategies. Research also reveals the importance of timing when choosing the best market entry strategy. This attribute mostly applies to an airline’s potential to outwit its competition. “Such first mover advantages which also result in repercussions for ownership advantages seem to be substantial given the importance of cooperative internationalisation modes” (Albers & Heuermann, 2009, p. 21).

Recommendations, Implications and Contribution to Study

Recommendations

Although this paper has shown that European airlines could benefit from venturing into the Asian aviation market, the findings from this study show that there is no shortfall of airlines to serve this market. Therefore, for European low-cost airlines to meet their intended objectives in these markets, they need to build a competitive advantage over their Asian rivals. According to Klug (2007), these airlines could realize market success by improving their service provision advantages. This recommendation stems from studies that show how low-cost airlines cannot effectively compete on a cost structure alone (Albers & Heuermann, 2009).