Introduction

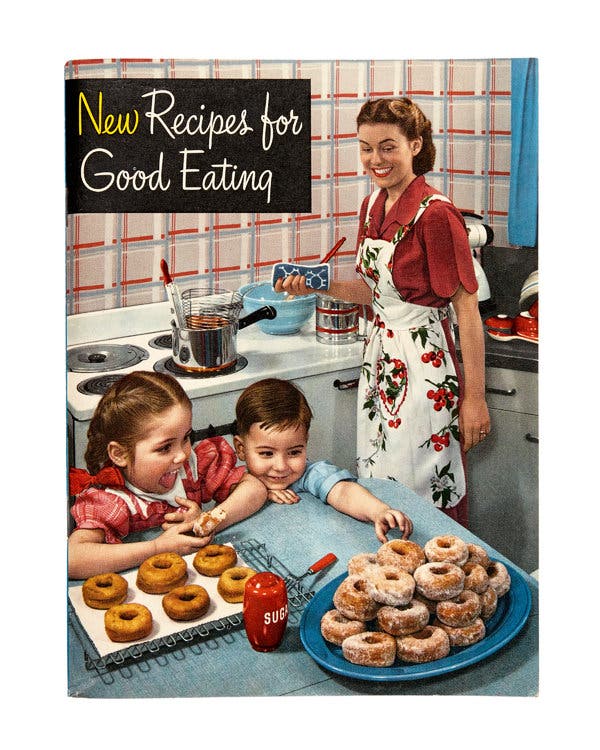

Food photography has developed throughout time via improvements in technology, techniques, and interest. Photos of food have been taken, shared, and appreciated for decades, from ambrosia salads in the 1970s to the current trend of upside-down acai bowls and elaborate latte art. The trend of food photography began as early as the 1800s (Giesbrecht). In the middle of the 20th century, this trend began to be actively involved in advertising, and, as shown in Figure 1, vivid images of food were a characteristic feature of attracting attention.

The cookbook depicted a clean kitchen, a housewife with two children, and a plate full of doughnuts. This was an embodiment of the American dream family on which marketing specialists wanted to place an emphasis. It initiated the idea of food photography, which focused on the people and the product. Further developments in technology and various experiments with it introduced a variety of options to experiment with and create a separate form of photography. In modern food photography, emphasis is placed not only on the food itself but also on a lifestyle, including peculiar cultural characteristics. Over the last half-century, there has been a dramatic shift in the way photographs of food are taken. Experiments with the features of the shooting process and photographic compositions show how cultural perception trends have changed, how technology has influenced this, and which familiar styles have lost their relevance with technological progress.

The First Food Photo

The art of food photography originated in the middle of the 19th century. As early as 1845, William Henry Fox presented such a photograph, or rather a daguerreotype, in which he showed two fruit baskets (Figure 2). Such a composition was in many ways reminiscent of traditional French still lifes of past centuries. However, Fox’s photography, called The Pencil of Nature, was not a painting but a photographic art. Since then, new trends in food imprinting have begun to emerge. Particularly pronounced styles began to replace each other in the middle of the 20th century; nevertheless, Fox’s photograph is considered the ancestor of all subsequent images.

1950s-1960s: Experiments with Different Camera Controls and Lighting Strobes

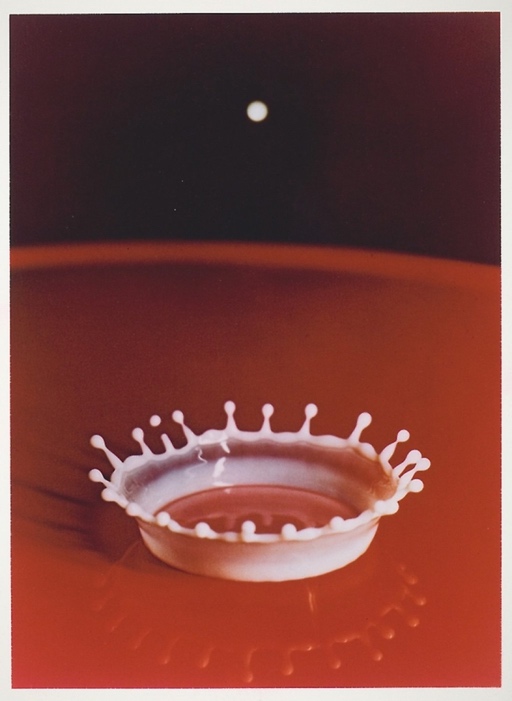

The change was slowly introduced by Harold Edgerton who conducted an experiment dubbed the Milk Drop Coronet. It included using shutter motors and strobe lights to record a splatter of a milk drop, thereby capturing a moment in time (Figure 3). This ground-breaking shot and process inspired the creation of the electric flash, which permanently altered still-life and food photography (Giesbrecht). Although this is undoubtedly a watershed moment for the development of food photography, the field did not immediately shift.

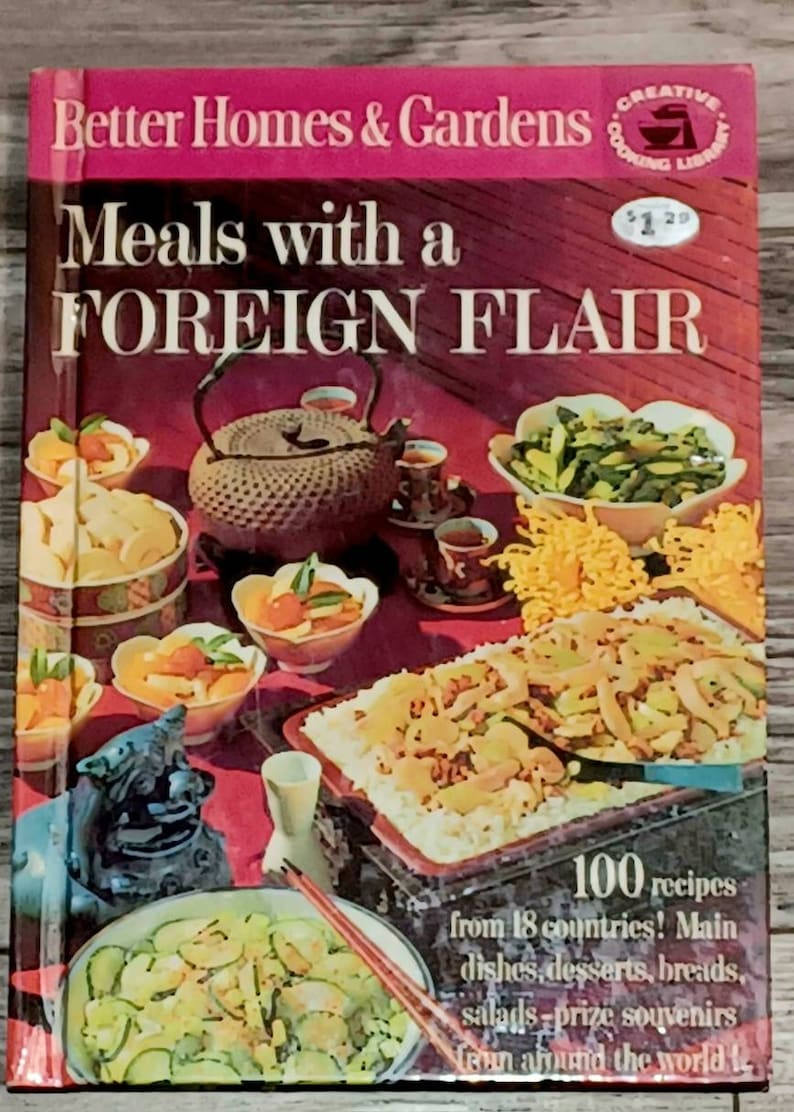

In the 1960s, wide shots showcasing the whole dish in an unremarkable background were the norm for food photography back then. This could be seen in the Better Homes & Gardens’ book Meals with a Foreign Flair. During this era, the most typical approach to food photography remained the preparation of cooking recipe books (Giesbrecht). This medium followed the industry to the current times and continued to be one of the most popular types of commercial food photography. Today, such publications as the one in Figure 4 are sold everywhere, showing a long-standing interest in the cultures of different peoples’ cuisines since the last century.

1970s: High Fashion Food

In the 1960s-70s, film cameras were the norm for food photography, and elaborate sets were built to showcase the dishes being shot (Giesbrecht). Mirrors, glass, and aluminum foil were common tools of photographers for improving their subjects’ appearance (Giesbrecht). Food was often depicted in stylized forms in print media such as cookbooks, periodicals, and ads during this time period. However, the low resolution and inaccurate colors made it difficult to portray the food’s genuine aesthetic appeal.

At that time, Irving Penn, a photographer specializing in food photography, gained particular popularity. He had a reputation for being precise and minimalist, expressing the essence of cuisine in a spare and beautiful way. To highlight the elegance and smoothness of his subjects, he would often utilize a plain white backdrop and gentle lighting (Tartsinis 302). His contributions to Vogue and the cookbook “Still Life” attest to his skill.

Aside from flared pants and hippie tops, the 1970s also provided other great things. In addition, they introduced a lighthearted period in food photography. Even though they were intended for the kitchen, these commonplace items took on a new aesthetic value as works of art. Peter Fischli and David Weiss styled sausages and pickles as though they were models in 1979 for their “Wustserie” (the “Sausage Series”) (Giesbrecht). The photographs reflected the artist’s appreciation for banal items and his sense of humor. Ambrosia salad, demonstrated in Figure 5, was a popular dish at 1970s-style dinner parties when aspirational cooks showcased their best dishes.

1980s: Props in Food Photography

The 1980s saw the emergence of a trend toward more conceptual food photography strategies. In particular, additional props began to be used to structure complex compositional formats. This type of photograph was characterized by greater blurring, thereby making the images more romantic and non-standard (Giesbrecht). Together with food, flowers, toys, and other elements were added to the frame, which made it possible to build a specific plot composition. This complex format is shown in Figure 6, where the auxiliary objects are clearly visible.

Commercial photography in periodicals, cookbooks, and classic advertising took acquired a more dramatic tone between the decades of the 1960s and the 1990s. The 1990s, however, witnessed a return to a more naturalistic aesthetic. According to Giesbrecht, during this period, people began to appear more often in food photographs, demonstrating the direct role of chefs in cooking. As a result, the 1990s marked the beginning of the era of narrative food photography (Bright). It was no longer only the food itself that made a meal memorable but also cooks and restaurants. Ad campaigns shifted away from slick, staged food photography to more realistic depictions of what really goes on in restaurants and kitchens. In the 1990s, a cookbook evolved into something more than only a collection of recipes (Giesbrecht). Instead, it turned into a picture album showcasing the finest dishes, awards, and the chef’s personal life.

This era was also renowned for the time of Bob Carlos Clarke’s food photography. The macho, noisy, meaty, and hedonistic kitchen of Marco Pierre White was documented by this photographer, renowned for his sensual black-and-white images of females and automobiles (Bright). Before this, photographs of high French cuisine were static and fussy; now, with all of the action and steam, they convey a sense of macho and passionate culture (Bright). White is treating cooking like a sport and drinking water like an athlete. The photographs challenged conventional wisdom about how to shoot elegantly presented gourmet food since they were full pages like those in a magazine rather than a cookbook (Bright). Thus, one can observe how the cultural interests of the public influenced trends in photography.

2000s: Utilizing Digital Cameras for Better Food Photos

The new millennium marked the transition to digital methods of photography, which was certainly reflected in the style of food presentation in the media. Instead of artificial lighting in studios, natural locations with daylight began to be used (Giesbrecht). Due to improved image quality, photographers began to place more emphasis on the details of individual products rather than dishes as a whole, which, in turn, increased the opportunity for influencing the observer. New shooting angles started to appear because the public was used to simple vertical and horizontal formats (Giesbrecht). As a result, improved details became a prominent feature of food photography during that period.

Food photographers now have a place to expose their work to a broader audience, which is largely due to the proliferation of the internet and social media sites like Instagram. Digital photography allowed photographers more freedom to alter photos to their liking. Due to this, food photographers were able to make pictures that looked tastier and were thus more likely to be shared. J. Kenji López-Alt, a photographer living in the Netherlands, was a major figure during this time period. López-culinary Alt’s photography, featured in Cook’s Illustrated, was renowned for its precision and fidelity to the subject matter (Martin). To capture the natural splendor of his subjects, he often turned to professional-grade digital cameras and lenses (Martin). He also made use of cutting-edge photo editing methods like retouching and color correction to improve the overall quality of his work.

2010s: The Social Media Era

The ubiquity of smartphones with relatively good image quality has led to the fact that everyone can photograph food, and the foodstagraming trend has become massive. In an attempt to share moments of their lives, people began to take pictures of various dishes, and social media has become a convenient platform to popularize such photos. Giesbrecht mentions various individual trends formed in the context of this movement. As a result, the corresponding photographic filters appeared, and different challenges started to be launched, which, as shown in Figure 7, became commonplace.

The 21st century has marked a shift in the purpose of food photography away from highlighting a dish’s aesthetics and toward capturing the essence and experience of eating. Food bloggers, influencers, and stylists have recently become popular because of their ability to utilize food photography to convey narrative and emotion (Giesbrecht). Photographers that specialize in food are becoming creative by experimenting with lighting, composition, and such effects as shooting from above, utilizing props, and toying with shadows.

Emily Hlavac Green, headquartered in New York, is one of the well-known modern photographers. Green, who has gained fame for her mouthwatering photographs, typically uses narrative devices like props, lighting, and arrangement to make the spectator feel something (Emily Hlavac Green). Magazines including Bon Appétite, Food & Wine, and Time Out New York have highlighted her work, which demonstrates the widespread popularity of food photography.

2020s: Focus on the Ingredients

Still, life photography is making a comeback as photographers want to separate themselves from the social media craze of on-the-go food photography. As a result, one can see this transition in updated composition styles. When it comes to food, there is a new emphasis placed on using natural, unprocessed products and visually dissecting them using photographs of the individual components (Giesbrecht). The beginning of a new decade ushers in new fashions, and with it, a return to depictions of food that are more straightforward. A fresh emphasis is being placed on the components that go into a dish as well as using those components as props in the photos (Giesbrecht). Particular emphasis is placed on natural ingredients, which, being formed into complex compositions, allow for creating voluminous and bright pictures, which is clearly depicted in Figure 8.

As more photos of food are posted online, photographers distinguish themselves by combining their technical expertise and years of experience in studios. They search for fascinating shoot venues to generate dynamic photography that cannot be captured with the simple push of an iPhone camera button (Giesbrecht). This approach differs from the modern trend of taking photos on the go because, despite the lack of complex plans, such shots require advanced preparation.

Conclusion

Due to regular experimentation, the constant development of new technologies, and cultural shifts, the field of food photography has always undergone changes. This can be seen in the transition from the flashy advertising of the mid-20th century to modern digital photography, accessible to everyone. The widespread availability of cell phones has democratized the practice of food photography. More individuals can shoot and post high-quality images of their meals on social media. Due to this, amateur food photography has become more popular, spawning a whole new set of budding photographers. The ways in which meals are photographed and displayed have seen radical changes from the analog to the digital eras. Food photography has grown more accessible with the emergence of social media and cell phones, and it has developed into a way of storytelling and expressing emotions.

Works Cited

Better Homes and Gardens Editors. Meals with a Foreign Flair. Meredith Press, 1963.

Bright, Susan. “3 Food Photographers Who Changed How We Eat.” Saveur. Web.

Cowan, Katy. “Feast for the Eyes Tells the Story of Food in Photography.” Creative Boom. Web.

“Emily Hlavac Green.” Anderson Hopkins, 2023. Web.

Giesbrecht, Jordyn. “From the 1800s to Present Day: The History of Food Photography.” The Shutterstock Blog. Web.

“A History of Food Photography.” Pink Lady. Web.

Martin, Brett. “J. Kenji López-Alt Is Cooking up a New Kind of Perfection.” GQ. Web.

Tartsinis, Ann Marguerite. “Icons of Style: A Century of Fashion Photography, 1911-2011.” Fashion Theory, vol. 24, no. 2, 2020, pp. 293-304.

Wilson, Alexandra. “Best of Web – Mild Drop Coronet.” Flow Visualization. Web.