Fashion and the performing and visual arts have always been intertwined for those with the financial resources to indulge in one or all three. Fashion has also always been concerned with more than just covering nakedness or keeping off the cold and sun.

All over the world, and even in prehistoric tombs, what one wears has always been a mark of status, role, and affiliation, among many other characteristics.

It seems natural, therefore, that fashion, and fashion’s current most dramatic means of promulgating its newest innovations – fashion shows – should have adopted the characteristics of current performances and exhibits (Duggan 1-2).

The goal seems to boil down to ‘blockbusters or nothing’. It is possible to follow a logical path of development in fashion’s presentation of itself.

It has evolved from the crafting and wearing of clothing for strictly personal use, in earlier times, to mass-production, mass-marketing, and interdisciplinary collaboration, today.

The Ballet Russes, currently commemorated on its centenary at the Victoria and Albert Museum (Victoria and Albert Museum), is a type specimen of this latter sort of blockbuster arts/fashion/marketing combination.

Over the last century, fashion has appropriated many of the same functions as the fine arts. Fashion has thereby acquired all the political overtones and potential cultural impact that go along with that sort of enterprise (Duggan 1-2).

Designers have used their role to make statements far removed from fashion (Duggan). There are few better early examples of this sort of appropriation of the role of one art form by another than in the Ballet Russes.

This ballet company marshaled a massive outpouring of talent under the leadership of Sergei Diaghilev in the first decades of the 20th Century.

The artifacts currently on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum’s centenary exhibit demonstrate this creative cross-fertilization clearly.

Designers over the last several decades have tried to create multi-media, multi-platform political and social statements that were – by the way- fashion shows (Duggan). Today’s designers would do well to look back to Diaghilev for some tips on vertical and horizontal integration.

The close connection of fashion and art is, as noted at the outset, not entirely new, and always carried more meaning than simply clothing the body, especially given the constraints on women1.

The links between fashion, commerce, and the presentation of an artistic, or even political, statement through what we would recognize today as a fashion show had its inception at the turn of the century.

Then, as Duggan points out, the clothing manufacturers put their products on models and paraded them down a runway for the first time (Duggan 2). This was a step forward from merely showing a dress sample in the window of the shop or designer’s studio.

They became more than a mere display of the designer’s most recent clothing ideas to the fashion press, or presentation of options from which wealthy women might subsequently select in the designer’s showroom. Fashion shows became performances.

Since then, the trend has largely been in the direction of increasing elaboration, as noted by Duggan (Duggan 2).

Manufacturing centralized, and stores increased in size, as did the middle class possessing discretionary income. At the same time, so did the technical sophistication involved in the staging of a fashion show (Duggan).

Over time, the act of marketing one individual dress to a well-heeled woman decreased in importance compared to selling thousands of similar dresses in large department stores.

This vertical integration meant that the ideas presented in a fashion show were soon or simultaneously accessible in a cheaper range of the same designer.

This trend was accompanied by a push to diversify and integrate horizontally. Selling even a thousand dresses was not enough; the designer needed a purse and shoe line, a perfume, and even a house wares imprint.

One needs to look no further than Pierre Cardin or Ralph Lauren for examples. A designer could eventually advertise their whole brand, their concept, and their personal world-view through the ambiguous vehicle of the fashion show.

As the decades have progressed, this link between fashion show and almost everything else in the world in addition to selling a group of clothing designs has become ever stronger.

Dopp, reviewing a work by Davis, notes that fashion around the First World War took on the role of dictating to the well off what they should wear (Dopp).

It is useful to remember the role of changes in fashion, promulgated by the fashion press and fashion shows, in freeing women for active helping roles in the First World War.

This would not have been possible without shortened hemlines, and less constrictive undergarments (Thomas, 1914-1920: Towards Dress Reform).

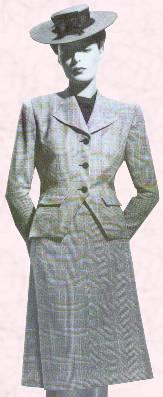

Consider, too, the role of fashion shows in garnering support for the World War II effort. The wartime design pictured here (Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers) was created by the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers, which included names such as Molyneux, Hartnell, Stiebel, Delange, Mosca, and Hardy Amies.

The label, CC41, was designed by Reginald Shipp, and stood for the Clothing Control 1941 (Thomas, Rationing and Utility Clothing of the 1940s).

Fashion has not only had a mutual effect with the wider world over time (consider the far-ranging impact of the Flapper styles on women’s roles).

It has been affected by innovations and trends in fields as apparently unconnected as chemistry (consider the invention of rayon, nylon and polyester (Routledge 959)), and popular social dances (Legend has it that both the Flapper skirt length and the short jacket of the modern Tuxedo jacket were a response to young people’s desire to dance the Charleston without restrictions.

The author of the recently acclaimed book, Apollo’s Angels, in a recent interview, noted that ballet was originally a social activity and hobby of the wealthy (for example, the Sun King, Louis XIV, who took daily lessons).

It was later performed for the wealthy by specialist practitioners from the less advantaged classes. It became a favored entertainment of Russian nobility. After the Revolution, ballet was a rare trace of the Tsar’s ancien regime that the Soviets chose to tolerate.

They even supported it and dragged foreign visitors to see it, especially since it required no shared language. Ballet was always associated with spectacle, whether in the French court, or even in the Soviet era, when tractors were a thematic element (Homans).

In all of its past incarnations, ballet has offered the opportunity for the creation of spectacles and visual inspiration off the stage and outside the theatre2.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the current exhibit on the Ballets Russes at the Victoria and Albert Museum demonstrates its immense impact on fashion at the time of its peak of popularity.

Diaghilev drew the best artists in all fields into his orbit and into ballet because he accorded their participation in performing arts as serious attention and respect as if they were in the fine arts (Harriman Institute). The list of his collaborators over the years is long and prestigious.

Stravinsky wrote music for Diaghilev. Picasso, Matisse, and De Chirico created backdrops and sets. Chanel, Goncharova, Larionov, Bakst, and Roerich designed costumes (Victoria and Albert Museum) (“Irina”).

There were many less well-known artistic names as well: N. Roerikh, G. Yakulov, B. Erdman, A. Ferdinandov, L. Khidekel, T. Bruni, P. Tchelitchev, A. Tishler, N. Akimov, G. Boriskovich, I. Sevastianov (Harriman Institute).

The Diaghilev Ballet Russes exhibit certainly fulfills the name of blockbuster. It has the requisite size (over 300 items), the marketing push, and the interdisciplinary tie-ins (for example with the London College of Fashion and the English National Ballet (Fashion Arts).

The VAM showcases costumes, backdrops, photos, and props, demonstrating the copious imagination involved in every production.

Many of the pieces were in the VAM’s collection already, the result of some clever purchases at Sotheby’s in past decades. This represents a clever use of material in the VAM’s inventory, and probably a cost savings as well.

The influences of these pieces must have been like visual blast of fresh air. Unlike the Fragonard-style wispy landscapes that we associate with older theatrical backdrops, these were visually arresting on their own.

The Firebird backdrop, with its mounting ranks of onion domes and typically Russian house shapes, is a far cry from the cute or twee.

It works just as well as a fabric design, a scarf, wallpaper, or an advent calendar. It celebrates the idea of Russia, and the best elements in Slavic folk tales. It evokes the Roidina (or homeland) of every Russian expatriate’s memory.

Consider also the gorgeous boots created for Igor. The elaborate decoration may have inspired generations of leatherworkers on both sides of the Atlantic.

For Europeans and Americans who had never seen real Russian styles, these images, and those of the peasant costumes also featured in the show, must have fueled several generations of Russophiles (Victoria and Albert Museum).

In the same way as Diaghilev and his cohort of artistic geniuses did, fashion designers today have gone far outside the mere selling of clothing. They have undertaken to introduce new ideas, uncomfortable ideas, and even unspeakable, revolutionary ideas.

Caroline Evans book on the edgy, disconcerting design displays of the 1990’s has been described as a vision of the dark side of fashion (Tredre).

The themes, locations, models, and finales of the shows she discusses clearly show the designers’ urge to have an impact far outside the stores where their goods are sold.

As she points out, the theme of a show can be carried consistently through the show’s music, hairstyles, jewelry, shoes, swag (complimentary gift) bags, choices of paper and typeface for invitations, programs, and other ephemera (Duggan 4).

Duggan identifies five different categories of these new hybrids of fashion and performance. These are: spectacle, substance, science, structure, and statement. There are examples in fashion shows of the 90s to the present in each of these categories.

In the category of spectacle, Duggan identifies several variables that a designer could modify to create an effect. She lists, “the type of model, location, theme, and finale” (Duggan 3). Gianni Versace is her pick for an innovator in this type of fashion show.

She points out that he was among the first to exploit the notion of a supermodel. A 1991 Versace show included lip-synching of rock music lyrics by his models, and thus created an enduring connection between the music industry and fashion (Duggan 3).

The late Alexander McQueen, another spectacle-maker described by Duggan, drew on the theme of mental illness, and capitalized on a then-current popular horror film, The Shining for his Spring 2001 show. The location was a transport depot.

It was large enough to contain a mini-set of the wintry isolation of the film’s setting. This was enclosed within a clear cube. The models are described as having been encouraged to prowl like mental patients (Duggan 4), or perhaps caged werewolves.

What might his messages be?

He could have been drawing our attention to the plight of the mentally ill, the thin line for all of us between fully functionality, our terrible dependence on human contact for safety and sanity, or the artificial barriers that separate those who are out in society versus those behind bars somehow.

All are possible and disturbing interpretations of these images.

In an earlier example of McQueen’s shows, described by Suzanne Moore, his 1995 show paraded models who appeared to have been abused. This caused a fuss because it seemed to suggest that those women could, or should, be mistreated.

However, the designer took the opportunity to counter this with a message about the need to avert the sort of real domestic abuse McQueen had observed in his own family. He also made a point about Scotland’s history of struggle for autonomy and land rights from the English government.

Suzanne Moore defends his un-pretty sensibility and sees it as intimately connected to fashion’s underpinnings, as follows, “For fashion is a brutal, predatory business.

It preys on the bodies of girls and the fingers of the child labourers and the aspirations of all the young designers who will never make a fortune. Still, there are rare people who do more than just make us change our clothes.

They change our minds.” (Moore, Alexander McQueen Changed Our Clothes and Our Minds – and, Boy, Could He Wear a Kilt)

Another example of spectacle (or anti-spectacle) is the Fall 2000 Galliano show that featured the theme of the homeless. Garbage and garbage bags formed part of the clothes.

This particular show garnered much coverage of the serious press, and of course, the free advertising that this implies (Duggan 4). What was the long-term impact of this show?

We still have homeless people. However, today we routinely use bags and other items made from recycled grocery bags – is this somehow related?

In the category of substance, she cites the work of Hussein Chalayan. The Fall 2000 show featured models putting on furniture as clothing. As Duggan points out, this emphasizes the process of creation, rather than a product that someone could wear out on the street.

Chalayan may have been playing with the notions of clothing as a furnishing of our life, and the idea of women’s past role as a chattel of men, like furniture.

These are abstract concepts, and while they certainly were expressed in an entertaining way, the impact comes from people talking about, and trying to figure out the meaning of the show.

Of course, the central element in this show, the furniture-clothes are probably un-wearable off the runway.

However, it is interesting that a recent invention by a student transforms from a coat to a sleeping bag. Was this inspired by Chalayan? Who can say?

Duggan describes the anti-fashion fashion shows of Hussein Chalayan as valuing substance over novelty, and all the nonsense surrounding branding and exclusivity (Duggan 6).

Viktor and Rolf are another example of designers mocking the whole concept of fashion, by, for example, selling perfume with no scent (Duggan 6). They have gained great visibility with their anti-fashion shows through the media hype that erupts over their artistic choices.

In the category of science and performance, Duggan points out the emphasis of Issey Miyake on innovative uses of fabrics. The designer has re-thought silk, pleats, and metallics in marvelous ways (Duggan 8).

His work is always a marriage of traditional craft with the most modern technologies (Paris Voice). In his Fall 1998 collection, his models were clad in foil, reminiscent of a Dr. Who scenario.

While his fans apparently find his designs easy to pack, it seems significant that his work is in so many museums (Muschamp). He has used his fashion shows as a way of exploring the limits of materials.

Duggan’s category of structure is perhaps the least accessible sort of fashion show performance, at least to non-fashionistas/os. Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garcons is one of her picks for this type of presentation.

She has been very innovative in fusing fabrics and using padded fabrics (Encyclopedia.com) and pleats in places and applications that are not intuitive.

These designs can seem alarmingly oblivious of the body, when viewed in a flat picture. Is the model wearing the clothes, or are the clothes wearing the model? However, Duggan assures her readers that they look fascinating in motion, like walking sculpture (Duggan 10).

Here again, it is difficult to avoid asking the question, ‘why’. For whom does Kawakubo intend these items? What is their function? Duggan provides one answer; some items were used in modern dance performances (Duggan 11).

Kawakubo’s shows, and those of others who focus on the structure of their clothes, tend to be simple, with the clothes themselves, in motion down the runway, speaking for the designer (Duggan 10).

In fact, in some cases, for example, that of the inscrutable Martin Margiella, the clothes might not ever appear, except as photographs or drawings. This removes all the sex appeal and frenzy from the display of the designs (Duggan 11).

Statement fashion shows include those of Miguel Adrover, who makes fun of the label obsession of the fashion world. His re-purposing of the Burberry look (see below) brought on a lawsuit.

Cleverly recycled garments and materials (some of the fabrics in the 2000 show seem to have been lifted from an upholsterer) and low-key avoidance of glitz characterize their presentations.

However, they cause an uproar nonetheless with their message of disrespect for the fashion establishment.

This uproar is advantageous to these designers. It reveals a clever manipulation of the media. If a fashion show makes a political or social statement of current interest, the show will receive media coverage from the mainstream press, not just the fashion press.

This is essentially free advertising, and is literally priceless, since it carries the name of the designer into the homes and consciousness of people who would never have even heard of the designer otherwise (Duggan 13).

Whether with disturbing images, or vivid and inspirational ones, fashion has the power to affect many more people than those who wear the styles.

In the same way that the colors, shapes, and images of the Ballet Russes percolated out of the ballet into the wider society, fashion ideas percolate out into people’s awareness.

Even those who will never buy a designer dress, attend a fashion show, or attend a ballet, will be touched by the performance of fashion and art.

Bibliography

“Irina”. “Russian Ballet in V&A.” 2010. Valley of Omsk.

“Vic”. “Review: “Fashion in the Time of Jane Austen”“, by Sarah Jane Downing.” 2010. Word Press.

Chalayan, Hussein. “Hussein Chalayan.” 2010. Google.com. Web.

Dopp, Bonnie Jo. “Review: “Classic Chic: Music, Fashion, and Modernism” By Mary E. Davis. (California Studies in 20th-century Music, 6.) Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006. [xix, 336 p.ISBN-10: 0-5202-4542-3; ISBN 13: 978-0-520-24542-6.” Notes 64.2 (2007): 288-91.

Duggan, Ginger Gregg. “The Greatest Show on Earth: A Look at Contemporary Fashion Shows and Their Relationship to Performance Art Volume 5 Issue 3.” Fashion Theory 5.3 (n.d.).

Encyclopedia.com. “Rei Kawakubo.” 2010. Encyclopedia.com.

Evans, Caroline. Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity, and Deathliness. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Fashion Arts. “English National Ballet Photo Shoot.” 2010. Fashion Arts. Web.

Green. “Coat Transforms into a Sleeping Bag: Warms Homeless in Detroit.” 2011. A Green Living. Web.

Harriman Institute. “Homage to Diaghilev: Enduring Legacy.” 2011. The Harriman Institute. Web.

Homans, Jennifer. “The Tutu’s Tale: A Cultural History of Ballet’s Angels.” Fresh Air. Terry Gross. Philadelphia, 2010.

Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers. “Utility Clothing of the 1940s.” 2010. Fashion Era.

Moore, Suzanne. “A Material World.” 2004. New Statesman. Web.

—. “Alexander McQueen Changed Our Clothes and Our Minds – and, Boy, Could He Wear a Kilt.” 2010. Daily Mail.

Muschamp, Herbert. “Easy to Pack: Harder to Understand.” 1998. New York Times.

Paris Voice. “Issey Miyake: “Making Things”.” 1998. Paris Voice.

Routledge, Christopher. Bowling, Bell-Bottoms, and Popular Culture. n.d.

Style.com. “2000: M. Adrover.” 2000. style.com. Web.

Swarovski. “Nutcracker Press Release.” 2010. Swarovski.com. Web.

Thomas, Pauline Weston. “1914-1920: Towards Dress Reform.” 2010. Fashion Era.

—. “Rationing and Utility Clothing of the 1940s.” 2010. Fashion Era.

Tredre, Roger. “Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Deatlhliness.” 2010. UAEGarments. Web.

Victoria and Albert Museum. “Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes.” 2010. Victoria and Albert Museum. Web.

—. “Diaghilev: The Private View.” 2010. Victoria and ALbert Museum. Web.

Footnotes

1 Consider that, in earlier times, for example, in the Classical period, and the medieval era, women had few socially sanctioned outlets for their creative talents. The products of their needles and looms served as their artistic canvases.

In later centuries, fashion served as a vehicle for communication between women, through the sharing of patterns for decorative needlework.

After the widespread availability of printed engravings, detailed drawings of the newest fashions were a way of sharing and disseminating stylistic changes and innovations across great distances.

Jane Austen uses the availability or inaccessibility of fashion drawings or patterns as a marker for how up-to-date a character is (“Vic”). These drawings, even now, are highly sought after for their purely decorative value.

However, the transmission of fashion ideas occurred from one person to another, face to face, and the fashion show was far off in the future. The act of clothing creation was also a person-to-person affair until well into the industrialized 19th century.

2 Even today, a new production of a beloved ballet, such as the recent new Nutcracker at the London Coliseum, is hailed for its spectacular aspects (Swarovski).

To assess the fashion impact of ballet, it is only necessary to observe even the youngest little ladies in attendance at this venerable Christmas event.

Note how many ballet-goers are dressed in faithful imitation of the Sugar Plum Fairy, when ordinarily their mothers would have trouble getting them out of leggings or blue jeans.