When it comes to discussing the significance of fashion as a socio-cultural phenomenon, many sociologists and psychologists make a point in accentuating the irrational nature of people’s strive to look fashionable. Such their tendency does make much of a sense. After all, having a very little practical utility to it (as perceived by most people), one’s obsession with the matters of fashion may indeed appear illogical, especially if the concerned individual is a man.

However, there is a good reason to think that the irrational appeal of fashion has to do with the fact the former serves a thoroughly practical purpose: it helps individuals to address their unconscious anxieties, which in turn causes them to feel much better about themselves. Specifically, by becoming affiliated with a particular fashion style, people can represent themselves in public as being associated with a higher social class.

Also, one’s commitment to wearing fashionable clothes results in endowing the concerned person with a distinctive sense of self-identity. This, in turn, empowers the individual rather substantially, within the context of how he or she goes about tackling the challenges of life. The validity of the above-stated will be explored throughout the paper’s entirety, concerning both the assigned reading materials and the external sources of relevance. The would-be acquired insights into the issue will consequently be subjected to an interpretative inquiry as a means of testing the soundness of the proposed hypothesis. The chosen research method adheres to the paradigm of qualitative research and the deductive approach to conducting it.

Probably the main challenge of researching fashion, as a socio-cultural phenomenon is that, despite the abundance of information, regarding the topic, only a fraction of it could be deemed analytical. One of the possible explanations for such a seeming inconsistency is that once subjected to an analytical inquiry, fashion will appear to be concerned with providing societal legitimacy to the instinctive predispositions in people. This, in turn, implies that the ontological premise of fashion happened to be the same as that of just about any monotheistic religion: the duality of human nature.

On the one hand, we are naturally predisposed towards seeking dominance, as something that increases our chances to succeed at biological reproduction. On the other hand, however, we understand that if we do it with too much enthusiasm, this will result in rendering us “socially dangerous”, as seen by others. This explains the essence of fluctuating dynamics within human society. As Simmel (1957) aptly observed, “The whole history of society is reflected in the striking conflicts… between socialistic adaptation to society and individual departure from its demands” (p. 542). Thus, people are naturally prompted to choose in favor of the safest strategy for proving to everybody else his or her socially dominant status.

This is where fashion comes in handy. By wearing fashionable (expensive) clothes, a person can ensure that he or she is being perceived as “special”: something that will automatically help him or her to win the affection of the representatives of the opposite sex. In other words, dressing up fashionably is the socially appropriate way for individuals to be exploring their atavistic anxieties in public, without contributing to the rise of social tensions in the locale.

The worst thing that can happen to a person overly committed to trying to look like the most recent fashionable trend suggests that he or she should, is being referred to as a “freak”: a small price to pay, in exchange for winning the reputation of being much “different” from the rest, and therefore potentially destined for domination. This explains why fashion trends are commonly discussed in terms of being “eye-catching”, “memorable”, “unique”, “revolutionary”, etc., but very rarely in terms of being tasteful or distasteful. What this means is that, contrary to what many people assume to be the case, fashion is not really about aesthetic refinement. Rather, it is about helping individuals to channel their atavistic anxieties in a way that does not undermine society’s structural integrity.

What are these anxieties? The foremost of them appears to be reflective of people’s unconscious strive to be seen belonging to a higher social class than they belong de facto, “Fashion… is a product of class distinction” (Simmel, 1957, p. 544). Regardless of whether we like it or not, but in the capitalist society, the measure of one’s worth is assessed to be directly relating to the amount of money in the person’s possession, which in turn defines the specifics of his or her class positioning. As fashion designers see it, visual distinctiveness has the value of a thing-in-itself, regardless of whether it proves to be pleasing to an eye or not. After all, one’s unconscious psyche perceives such a distinctiveness to be conveying the message of domination.

This is the actual reason why, as time goes on, fashionable trends never cease to adopt ever newer forms. In this regard, Simmel (1957) came up with another enlightening observation, “The fashions of the upper stratum of society are never identical with those of the lower; in fact, they are abandoned by the former as soon as the latter prepares to appropriate them” (p. 543). For example, a few decades ago the Swiss manufactures of luxury timepieces used to prefer gold as the actual material for making mechanical watches. However, ever since the Japanese-based watchmaking companies began to sell cheap metal watches that still appeared to have been made of gold (due to the applied golden coating), such a practice, on the part of most Swiss watchmakers, came to an end.

Nowadays, it is platinum that is considered to be the most fashionable material for luxurious watches to be made of. Platinum appears indistinguishable from iron, but it is much more expensive than gold. And yet, rich people prefer to have their expensive watches made of platinum: something that once again testifies to the validity of the suggestion that in the world of fashion, it is namely distinctiveness that is being appreciated the most. This distinctiveness must necessarily connote a high monetary value (even if doing it inconspicuously) while convincing the wearer of a fashionable item that he or she is indeed superior to the rest of people.

The most notable characteristic of fashion’s development through the last few decades is that, as time went on, fashion styles continued to become ever more “democratic”. Such a situation was brought about by the rise of the fashion industry through the second half of the 20th century and the increased affordability of fashionable clothes, especially given China’s role in counterfeiting brand-name items.

As Barthes (2013) argued, “Just as the place where one shops for groceries in today’s world is no longer a sign of one’s social status, so access to fashion can be opened up by the addition of the smallest (and cheapest) of details which affect the overall fashion form adopted” (p. 134). The common assumption, in this regard, is that fashion is nothing short of a social right and that, regardless of what happened to be one’s social status, the concerned person should still be in the position to afford to buy fashionable clothes.

It is indeed the case that, as of today, a person does not need to be very rich to gain the reputation of someone who makes a point in dressing up fashionably. Consequently, this causes many social scientists to doubt the appropriateness of assessing the significance of fashion from a class perspective. As a result, it now became a widespread practice among them to accentuate the phenomenological nature of fashion as something that has the value of a thing-in-itself.

The following suggestion, on the part of Blumer (1969), is perfectly illustrative, in this regard, “The fashion mechanism appears not in response to a need of class differentiation and class emulation but in response to a wish to be in fashion” (p. 543). Such a point of view, however, cannot be regarded as indisputable. The reason for this is that it implies that the term fashion is synonymous with the notion of aesthetics, whereas it was shown earlier that it makes so much sense referring to it as yet another socially observable sublimation of people’s deep-seated cognitive atavism: something that cannot serve any aesthetic function, by definition.

This brings us to discuss what social scientists consider to be yet another crucial function of fashion: to serve as the instrument of enabling ordinary people to feel being endowed with a sense of existential uniqueness. It is understood, of course, that one’s empowerment due to being much different from the rest is illusionary. The reason for this is apparent. The more existentially unique a particular individual happened to be, the less likely will it be for him or her to be willing to conform to the socially constructed and enforced code of behavioral ethics. Nevertheless, it is still possible to mislead conformist “hairless monkeys” into believing that they are indeed in the position to celebrate their “uniqueness”. This is being achieved through the legitimation of fashion as an integral part of contemporary living.

Hence, yet another prominent trait of fashion, as a whole: while making it possible for people to actualize their ego-centric aspirations, it strives to resonate with the currently dominant socio-cultural discourse. That is, fashion can be simultaneously described in terms of an individualistic and yet collectivist undertaking. As Barthes (2013) noted, “Fashion… flatters the universal desire for identity together with the no less universal desire to be a multiplicity of persons” (p. 122).

By applying a continual effort to following the most recent fashion trends, people attract the attention of others. Consequently, this assures them that far from being illusory, their existence does leave a mark on the surrounding social environment. At the same time, however, fashion aficionados can confirm to themselves that their “uniqueness” is, in fact, thoroughly normative, whatever illogical this may sound. This again testifies to the soundness of the suggestion that there is a strongly defined ambivalent quality to fashion, as the societal instrument of ensuring people’s psychological well-being.

As it was implied earlier, fashion would not be considered as a major artifact of human civilization had the very discursive premise behind it been not consistent with the way our unconscious psyche addresses life challenges. And, as psychologists are being well aware, it is in one’s nature to seek the most energetically efficient approach to solving a particular problem. In plain words, the lesser is the effort that a person applies into taking possession of a valuable resource, the better. Therefore, nothing is surprising about yet another characteristic of fashion, which makes the very process of following the recent fashion trends so appealing for a great many people: the fact that even the most aesthetically refined and sophisticated fashion trends can be imitated with ease.

On the one hand, it enables most ordinary individuals to appear fashionable in public using buying the counterfeited brand-name fashion items for only a fraction of a price. On the other hand, it provides yet additional momentum to the development of fashion, as a whole.

The reason for this is that, as it was suggested earlier, as soon as a particular fashion style (associated with the ways of the rich and powerful) ends up successfully imitated by the representatives of the lower social strata, the elites adopt an altogether different style. According to Simmel (1957), “In addition to the element of imitation the element of demarcation constitutes an important factor of fashion” (p. 545). One of the most obvious implications, in this regard, is that for as long as the domain of fashion is in question, the enforcement of copyright laws will most necessarily prove counterproductive.

There is even more to it: the imitability of fashion directly appeals to a “little monkey” that lives inside each of us. After all, among primates, one’s talent in imitating the actions of the pack’s most dominant members is the main precondition for the animal to have the right to be claiming the dominant position for itself. Therefore, by imitating the fashions of the elites, ordinary people are not being merely able to save money, but they also get to experience intense emotional pleasure from coming in touch with their true essence as “hairless monkeys” (Lamb, 2001).

The review of the thematically relevant literature allowed us to identify what may be deemed as the secondary forces that play an important role in increasing the emotional appeal of fashion to individuals. The first thing that needs to be mentioned, in this regard, is fashion’s ability to foster one’s unconscious predisposition towards existing in a state of constant perceptional and cognitive change. As Blumer (1969) pointed out, “Fashion serves to detach the grip of the past in a moving world” (p. 289). By ceasing to be associated with one fashion style and choosing to adopt another one, people can confirm to themselves that they continue to develop, in both the physical and intellectual senses of this word. This, in turn, results in reducing the severity of the “anxiety of inadequateness” in the concerned persons.

Another factor that contributes rather immensely towards the discursive legitimation of fashion is that the socially observable workings of the latter are perfectly consistent with how our unconscious psyche strives to adapt to the constantly changing external environment. By their very virtue of belonging to the Homo Sapiens species, people are naturally “programmed” to notice even the slightest changes within this environment while instantaneously focusing their attention on what their mind interprets as “strange”, “odd”, or “bizarre” (Guillo, 2012).

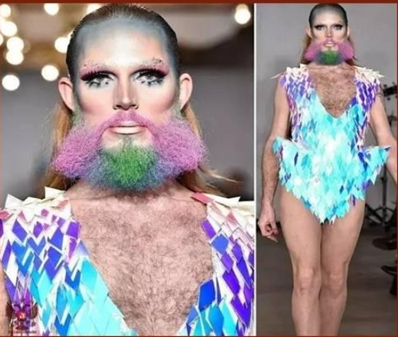

As a result, even those of us who do not follow the developments in the world of fashion, still cannot fight the temptation of taking a quick look at the TV while a particular fashion show is on. Partially, this also explains the designers’ practice of coming up with truly shocking fashion designs, such as the one seen below, even though this puts them in disfavor with most fashion consumers.

Finally, fashion serves to satisfy aesthetic cravings in individuals. After all, it has been revealed a long time ago that, as one succeeds in taking care of its basic physiological needs, it becomes only a matter of time before he or she begins to aspire to attain self-actualization. Developing a refined aesthetic taste is an important part of the process.

Before concluding this paper, let us summarize the main analytical acumens, yielded by the undertaken research. These are as follows:

- Fashion’s primary function is to help people to solve their class-related anxieties, which in turn reflect one’s instinctual preoccupation with trying to win a dominant social status within a specific environmental niche. By wearing fashionable clothes and leading fashionable lifestyles, individuals can experience the elusive sensation of superiority over others.

- Fashion proves to be a great asset, within the context of how men and women go about celebrating their self-identity. Even though most people believe that, in this regard, fashion’s role is rather supplementary, this does not seem to be the case. Quite to the contrary: in many cases, fashion serves as the actual source of ego-centric distinctiveness for many individuals who aspire to attain social prominence.

- As an existential pursuit, fashion is fully consistent with a number of the instinctive predispositions in individuals, such as their unconscious desire to imitate the application of an extensive effort into accomplishing things.

It is understood, of course, that the acquired analytical insights into the subject matter are far from being deemed exhaustive. Nevertheless, there is a good reason to believe that they are thoroughly legitimate, in the discursive sense of this word. Because of this, it will be appropriate to suggest that, despite the social scientists’ tendency to refer to fashion in terms of a civilizational artifact, such a practice cannot be deemed thoroughly justified.

The rationale behind this suggestion is clear: the obtained interpretative data implies that there are strongly defined atavistic overtones to what prompts people to preoccupy themselves with the matters of fashion, in the first place. The ways of fashion are indeed not quite as mysterious as it is commonly assumed to be the case. The author believes that this conclusion correlates well with the paper’s initial thesis. In the future, researchers should focus on identifying the actual link between the strength of one’s commitment to fashion, on the one hand, and the morphogenetic structuring of the concerned person’s brain, on the other.

References

Barthes, R. (2013). The language of fashion. New York: Bloomsbury.

Blumer, H. (1969). Fashion: From class differentiation to collective selection. The Sociological Quarterly, 10(3), 275-291.

Guillo, D. (2012). Does culture evolve by means of Darwinian selection? The lessons of Candide’s travels. Social Science Information, 51(3), 364-388.

Lamb, K. (2001). Evolutionary origins: Pathways of the human predicament. Mankind Quarterly, 41(4), 449-455.

Simmel, G. (1957). Fashion. American Journal of Sociology, 62(6), 541-558.