Introduction

Subjecting pre-existing economic models, closely associated with the moods of the era, to critical analysis in terms of historical dynamics, it is possible to discover that the definition of the economy does not remain unchanged, but rather is continuously being modified in response to the specific demands of society. This is particularly evident in the study of contrasts: while feudal and slaveholding natures primarily defined the economies of the first human settlements, the modern world tends to adopt smart economic systems. The fundamental difference between these sides of the development of society’s economic sphere lay in what ideas and moral principles were foundational and the establishment of specific systems of trade and monetary relations and the recognition of human dignity as a socially significant resource.

To put it another way, the most progressive models of smart economics aim at two goals at once, namely the development of high-tech industries combined with the assignment of acceptable social status to vulnerable groups. Nevertheless, despite the seeming clarity of the term “smart economics,” it is essential to recognize that, in fact, this concept has no permanent definition, so the interpretation of the phenomenon depends only on what ideas the authors are committed to.

In particular, some of the researchers have attempted to analyze the tenets of smart economy models in the context of sustainable city development, while others have applied these principles to given direction industries (Anand and Navio-Marco, 2018; Lyon, 2019; Schönleben, Mentschel, and Střelec, 2020). Regardless of assessment specialization, however, the smart economy continues to be closely associated with gender equality issues.

The core of the identification of smart economics is defined both by feminist Marxist theory and by an orientation to the main results of neoliberal state policies. Of paramount importance in this issue is the recognition that economics views human beings, regardless of gender, primarily as significant intellectual capital that is useful for increasing production capacity. In other words, it is suspected in this context that when women have equal opportunities with men — not formally, but in fact — this increases the number of trained workers in the economy and increases competition for crucial positions.

In turn, competition in the labor market corresponds to a better price-quality ratio of labor and gives employers the opportunity to invest, create new jobs, and stimulate further economic growth. Marxist feminist theory is based on these ideas, identifying the institutions of private property as the root of female oppression and dependence on the male gender (Seneviratne, 2018). Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to assume that a smart economy focuses only on increasing the number of women in low, middle, and managerial positions.

On the contrary, the central reference points of this progressive model of societal development are to achieve outcomes in which the major problems of our time, be they poverty, low availability of education, mortality rates, and adequate health care, are addressed. From this perspective, the increased participation of women in economic life increases diversity and competitiveness, which, in theory, should be the tools for achieving the goals mentioned above.

A Historical View of Gender Equality

For decades, the idea of gender equality as a central tenet of sound economics has been conceived and shaped into a coherent theory that has become a weighty model for the development of economic institutions today. However, there is no doubt that society was not interested in gender equality issues in the early stages of the economic development of civilization. Without specifically examining the peculiarities of women’s position in the financial systems of agrarian society, in which the sale and possession of slaves as a potentially important economic unit was a significant feature of the economy, it is essential to discuss the changing gender equality agenda over the last century.

Thus, it is worth noting that there has been a persistent global trend toward the deep integration of women’s gender into the economic system. In particular, as early as the beginning of the twentieth century, most women around the world were forbidden to engage in commerce, or if allowed, it was perceived as unconventional and unconventional. According to Yellen (2020), only twenty percent of all women and five percent of married women were gainfully employed for the period, while the rest were housewives taking care of children and the home. Young age was predominant among the working women, and often marriage was accompanied by loss of employment and a woman’s withdrawal into the family.

The preconditions for these figures were both the low socioeconomic status of women and the prevalence of strong gender stereotypes and the low availability of education. Of the two percent of young people between the ages of 18 and 24 enrolled in higher education, only one-third were women (Yellen, 2020).

Nevertheless, mores were gradually changing, and by the 1930s, there was a tremendous increase: nearly fifty percent of single women and twelve percent of married women were becoming gainfully employed. By 1970, the numbers were even higher: it was fifty percent single and forty percent married women. Since the 1990s, women’s economic activity rate has risen even higher, reaching 74 percent, compared to 93 percent for working-age men.

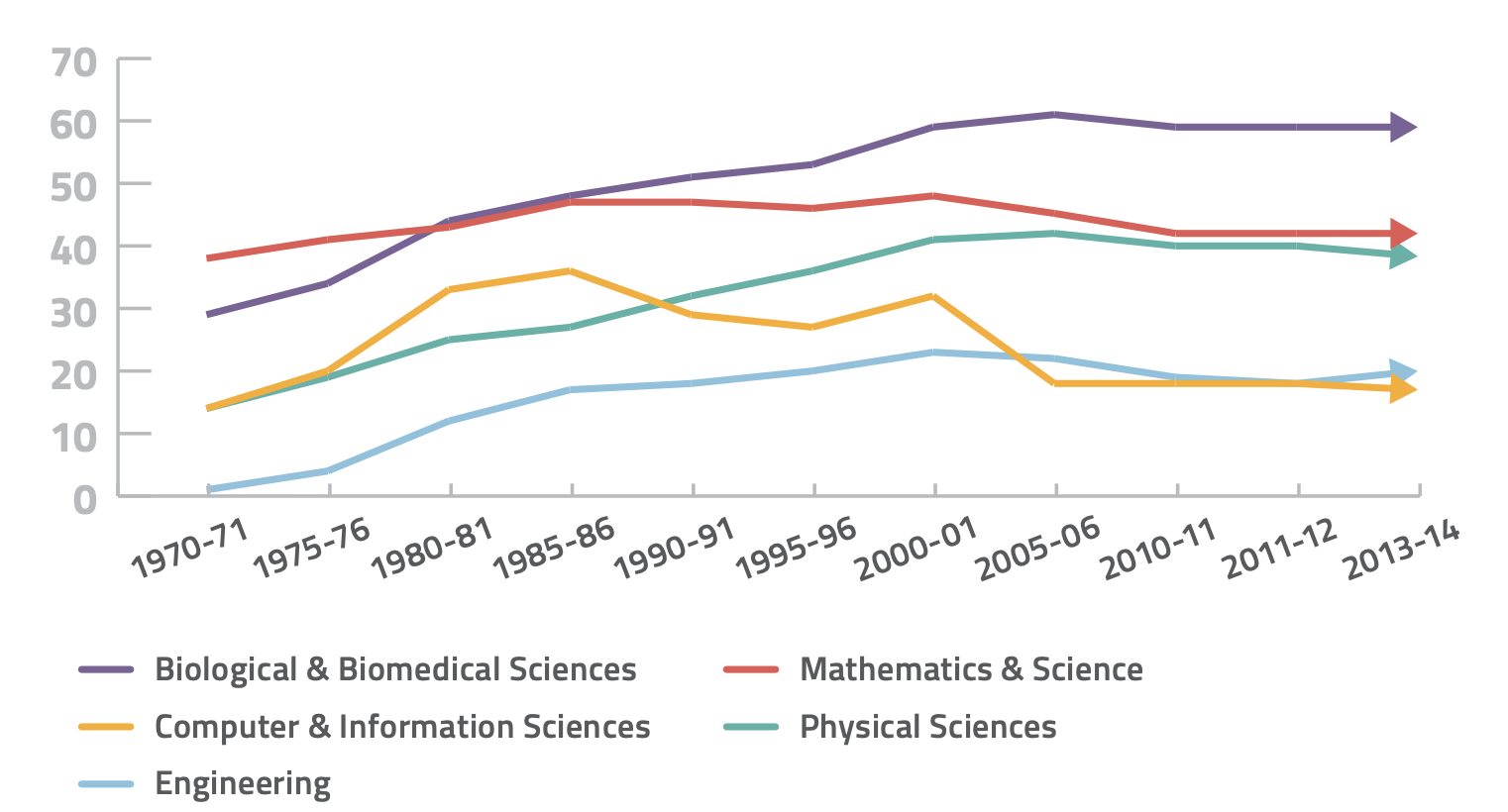

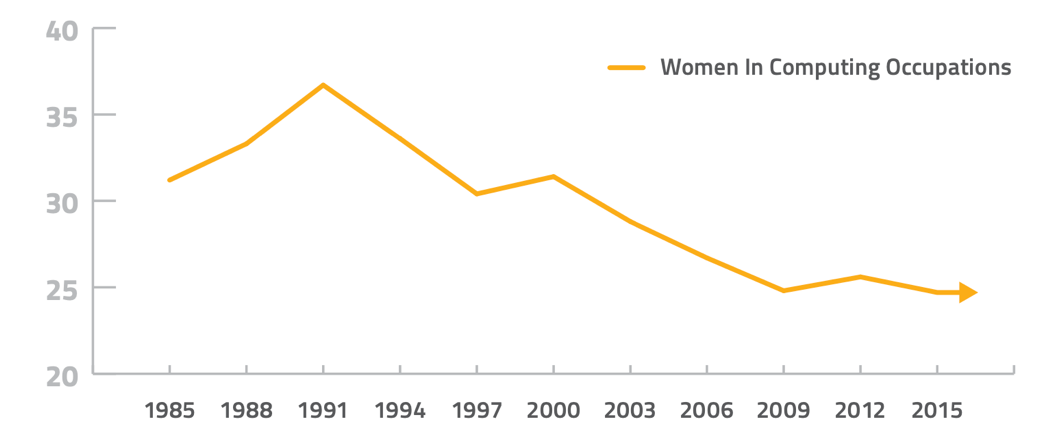

This rapid growth was accompanied by recognition of the utility of a highly educated female resource for societal development, so the share of qualified women in the total number of graduates increased markedly, as depicted in Figure 1. More and more women were moving from being low-skilled employees, such as seamstresses, nurses, or secretaries, to being fully recognized employees whose duties required highly intellectual or physical skills: surgeons, managers, and professors. The trend toward an overall increase in women’s participation in business has continued to this day, although there may be noticeable declines in specific specializations, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Turning to statistics relevant to the economy of today’s world highlights some intriguing patterns. In particular, women account for more than 66% of all work, even though the total income level is only 10% (What do we know, 2020). Wage inequalities are also noticeable: men are paid on average 128% more for the same work in the agricultural industry. Ultimately, this means only that achieving gender equality on the road to a smart economy is only a matter of time. It follows that with proper human resource management and gender-positive state policies, it is possible to achieve full balance.

The Importance of Gender Balance in the Economy

According to the prevailing concept of smart economics, ensuring gender equality is one of the factors in achieving sustainable development and adequate economic growth. Without dwelling here on the possible negative consequences of such equality and the conditions for its achievement in practice, it is essential to measure and assess what possible benefits balancing the rights of women and men entails in the context of economic engagement.

As shown earlier, the proportion of women in business has increased markedly but still remains unequal to that of men. In particular, while women make up about 49.6 percent of the world’s population, labor force participation in the formal sector is limited to 40.8 percent (What do we know, 2020). In other words, the policies of most of the developed world are aimed at achieving equality but are still far from the ideal.

Meanwhile, the balance of male and female genders in commerce has a number of significant benefits for humanity. Numerous contemporary studies suggest that the higher the level of female participation, the better the economic outcomes at both companies, national, and global levels (Hvidt, 2018; Jacobs, 2018). Of particular note are Credit Suisse Bank studies measuring the relationship between individual company gender policies and performance metrics. It has been shown that the higher the mix within a company’s governing grain, the higher its performance in the stock market (Credit Suisse, 2019).

According to data current by the end of 2019, gender diversity in management has doubled over the past decade, surpassing the 20 percent mark. According to Nations (2016), for those companies in which women held at least three executive positions, there were notable high scores on all of the most relevant criteria. In other words, companies whose management departments exclude women and emphasize strictly male participation have seen a decline in critical indicators of financial success (Keefe, 2015). The above confirms that the role of women in business is difficult to underestimate. However, it is essential to look more closely at what makes organizations successful: women’s participation or gender equality.

The economic rationale for success in achieving gender equality in the corporate environment is determined by numerical analysis. This paragraph discusses different perspectives on how effective it is to involve women in business. For instance, according to Morad (2019), the world economy could rise nine points if only U.S. companies followed the same gender policies as the Norwegian authorities. While it is known for the fact that it is the European powers that are famous for prioritizing balance, many U.S. firms have long outperformed them (Credit Suisse, 2019). Meanwhile, authoritative sources confirm the economic benefits of gender equality but diverge on the specific numbers that illustrate the impact. More specifically, Colby (2015) reported an increase in global GDP of more than 26 percent, to $28 trillion, if gender balance were achieved.

On the other hand, if women’s employment rates in OECD member countries alone were to match Sweden’s, then world GDP would increase by $6 trillion (Women in work index, 2020). Woetzel et al. (2015) argued that with ongoing trends in closing the gender gap, global GDP could be increased by $12 trillion by 2025. From the above, it is clear that the advancement of women is, in fact, an important goal for economic development, but the exact estimate is highly dependent on the factors of analysis.

On the other hand, the inclusion of women in business, and thus increasing the gender diversity of the company, becomes a catalyst for increasing the useful indices of the state. Empowering women to control their own destiny and choose development paths is the reason for a noticeable improvement in women’s quality of life, which itself affects the level of happiness in the country. Generally speaking, the higher the gender diversity in national political, corporate, and other social institutions, the happier the country’s population. This, in turn, increases the investment and tourism attractiveness of the region and therefore has a positive impact on the economy of the state.

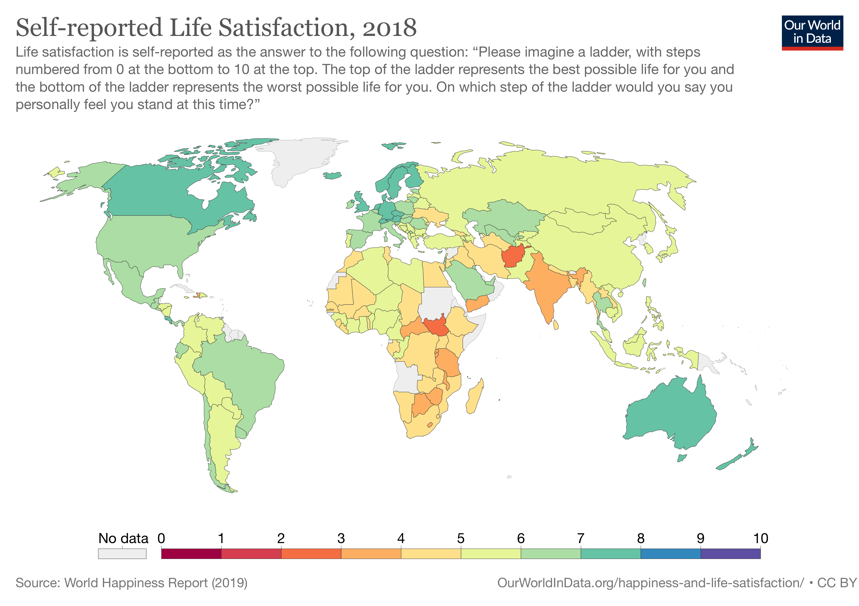

Furthermore, it is erroneous to believe that the increase in the happiness index associated with the achievement of gender equality is characteristic only of women, who are the beneficiaries of the relevant policy. Audette et al. (2019) have shown that such gains also benefit men. Such a thesis can quickly be confirmed by a careful study of the correlation between the level of happiness of the population of individual countries and their characteristic gender gap. The map in Figure 3 unambiguously reflects data from global population surveys on satisfaction with the quality of life, according to Ortiz-Ospina and Roser (2017).

A cursory analysis reveals that countries in the Americas, Europe, and Australia have the highest happiness index scores. When one turns to the data on gender equality within selected parts of the world, one finds the expected correspondence between the two indices. To simplify the visual perception of supporting numerical information, the data are formulated in summary Table 1. Statistical analysis conducted with MS Excel software showed that the level of correlation between the values is 0.78, which indicates a relatively strong positive correlation.

Table 1: Summary of data regarding individual nations’ life satisfaction level and index scores of gender equality (Ortiz-Ospina and Roser, 2017; Women in work index, 2018).

A third significant benefit of women’s involvement in the economy is the synergistic phenomenon called maternal altruism. First of all, it should be recognized that it is impossible to study human capital without applying a gender approach: this is because human capital is a reserve of individuals, and gender stereotypes cause gender imbalances in the socio-economic sphere. The very presence of such stereotypes explains the difference in the formation, accumulation, and use of human capital between men and women. Therefore, women’s role in the economy is traditionally associated with maternal care, including for the next generations.

Some micro-level studies in Guatemala and Brazil have pointed out that when gender diversity in the apparatus of governance increases, the quality of children’s nutrition naturally improves (Robles, 2020). In other words, the inclusion of women improves the chances of a child population to live a comfortable and secure life.

Gender Equality in the Smart Economy: An Agenda

While recognizing the apparent benefits of increasing the proportion of women in the economy of today’s world, it is essential to discuss the current situation in the global marketplace. Numerous studies have already confirmed the high impact of engaging all genders and thus achieving a certain balance, so by now, there are several essential trends for discussion on the issue of gender equality (Hvidt, 2018; Jacobs, 2018; Berik, 2017). First and foremost is the universally recognized global Sustainable Development Goal, according to the United Nations.

One of the seventeen sustainable development goals set by the U.N. for the period up to 2030 is the achievement of gender equality in all socially relevant spheres of life. More specifically, this refers both to the elimination of all forms of discriminatory policies against women and girls, including violence and to the recognition of the value of unpaid mother and wife labor through social rewards. Although historical analysis has shown in detail that the gender gap between men and women has rapidly decreased over time, it is still far from the theoretically ideal balance. It is important to recognize that such data are often averages, and while women’s advancement indices are high in European Union countries, in traditionally patriarchal states such as Mexico or Korea, the figure does not exceed 40 out of 100 (Women in Work Index, 2020).

This, in turn, leads to a significant gap between boys and girls, men and women within such countries, and is manifested in all the characteristic consequences. In particular, one factor in such a significant imbalance is the higher level of domestic violence against children, and especially girls (Klevens and Ports, 2017). Generally speaking, economic inequality between the two genders continues to be large in several countries with conservative governance, and this is a predictor of the harsh treatment of children.

Another significant factor describing gender equality in today’s smart economy is the desire to follow fashion. Although the decision to increase the level of women’s involvement in the economic sector of life in most cases is due to the natural mechanisms of globalization and recognition of women’s social status, one cannot rule out the purely reputational interest of company representatives. In particular, the granting of managerial positions may not always be justified by the numerous theoretical calculations and proofs of the economic efficiency of such policies, but rather by the desire to demonstrate the modernity of company leaders and the adherence to the agenda.

When discussing this phenomenon, it is impossible not to recall the recent scandal in Paris related to the ratio of male and female genders in the city’s managerial sector. More specifically, for the mayor’s office of the French capital in 2013, a legal prohibition on a gender gap of more than twenty percent was established: according to the text, the number of men and women in managerial positions had to be at least 40 percent for each, but it was better than the number be distributed equally (Jacquemart, Revillard, and Bereni, 2020).

This decision seems like an obvious strategy to respond to public feminist demands, and, moreover, is justified in the context of the essay under discussion. Nevertheless, by 2018, the number of women in the Parisian administration was 11, whereas there were only five men. As a percentage, this disparity was 69 to 31, which violated a previously established rule: the result of this gender imbalance, skewed toward women, was a fine of $109,369 (Wojazer and Woodyatt, 2020). It is hardly possible to determine the motives of Paris City Hall leaders in such an unequal hiring and deliberate violation of established law, but it might seem that the decision was motivated by a desire to conform to feminist fashion.

Finally, the last discussed pattern of the contemporary agenda in the context of this issue is the recognition of the importance of investing in women. Admittedly, the inclusion of women’s gender in the global economy benefits all stakeholders. In addition to the apparent benefits discussed above, it is important to note that the increased level of female participation in business naturally generates demand for professions related to child and home care: the higher the active participants in the market, the higher the aggregate demand. For example, a highly educated career mother can hire a babysitter to take care of her child, which shifts a number of tasks from the woman to the employee. Recognizing this benefit, many countries are actively investing in women to facilitate access to university and increase employment levels.

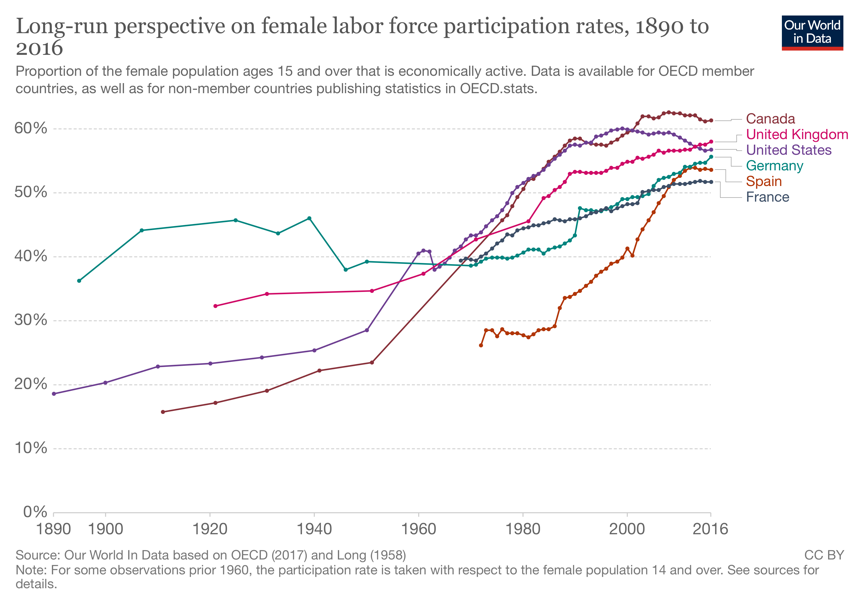

For example, a reference to Figure 4 reveals that over the past 130 years, women’s employment in most developed countries has risen as expected. This, in turn, is also associated with a general increase in female education and literacy, so it is reasonable to assume that investing in girls will yield positive results. Thus, Chant (2016) confirms these assumptions and shows that today’s economy intensifies women’s engagement to achieve gender equality. In other words, according to the author, the economy stops being smart and gets smarter. Based on this data, it can be predicted that the gender gap will continue to narrow in the coming decades, and thus the global economy will become more efficient.

Conclusion

To summarize the above, it is important to recognize that the problems of gender inequality in modern economies remain a pressing issue. Although the role of the female gender has significantly increased in comparison to the socioeconomic status of women in agrarian or pre-industrial societies, a balance has not yet been achieved. The desire to balance both genders — or at least to come close to almost equal numbers — is due to the apparent benefits of such equality. In particular, this relates to the growth of active market participants, increased healthy competition, and increased GDP both in individual countries and on a global scale. Furthermore, the effects of maternal altruism lead to the conclusion that women’s participation in the economy benefits the next generations. After assessing the available trends and data, it is reasonable to conclude that in the world of the future, the gender gap will be even narrower.

Reference List

Anand, P.B. and Navío-Marco, J. (2018) ‘Governance and economics of smart cities: Opportunities and challenges,’ Telecommunications Policy, 42(10), pp. 795-799.

Ashcraft, C., McLain, B. and Eger, E. (2016) Women in tech: The facts. Boulder: National Center for Women & Technology.

Audette, A.P. et al. (2019) ‘(E) Quality of life: A cross-national analysis of the effect of gender equality on life satisfaction,’ Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(7), pp. 2173-2188.

Berik, G. (2017) ‘Efficiency arguments for gender equality: An introduction,’ Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D’études du Développement, 38(4), pp. 542-546.

Chant, S. (2016) ‘Galvanising girl for development? : Critiquing the shift from ‘smart’ to ‘smarter economics’,’ Progress in Development Studies, 16(4), pp. 314-328

Colby, L. (2015) How do you boost GDP by $28 trillion? Gender equality would do it, McKinsey says. Web.

Credit Suisse (2019) Gender diversity is good for business. Web.

Hvidt, M. (2018) The new role of women in the new Saudi Arabian economy. Web.

Jacobs, B. (2018) ‘Women in economics,’ Economisch-Statistische Berichten, 103(4767S), pp. 1-2.

Jacquemart, A., Revillard, A. and Bereni, L. (2020) ‘Gender quotas in the French bureaucratic elite: The soft power of restricted coercion,’ French Politics, 18, pp.1-21.

Keefe, J. (2015) Why I am a male feminist. Web.

Klevens, J. and Ports, K.A. (2017) ‘Gender inequity associated with increased child physical abuse and neglect: A cross-country analysis of population-based surveys and country-level statistics,’ Journal of Family Violence, 32(8), pp. 799-806.

Lyon, S. (2019) ‘Business Anthropology’s Lens into Gender Equity: Assessing the impact of ‘smart economics’ in the coffee sector.’ International Journal of Business Anthropology, 9(2), pp. 33-50.

Morad, R. (2019) How gender equality is a growth engine for the global economy. Web.

Nations (2016) Leave no one behind: a call to action for gender equality and women’s economic empowerment. Web.

Ortiz-Ospina, E. and Roser, M. (2017) Happiness and life satisfaction. Web.

Ortiz-Ospina, E., Tzvetkova, S., and Roser, M. (2018) Women’s employment. Web.

Robles, C. B. A. (2020) “Gender equality as Smart Economics”: Questioning the assumptions behind the claim. Web.

Schönleben, M., Mentschel, J. and Střelec, L. (2020) ‘Towards smart dairy nutrition: Improving sustainability and economics of dairy production,’ Czech Journal of Animal Science, 65(5), pp. 153-161.

Seneviratne, P. (2018) ‘Marxist feminism meets postcolonial feminism in organizational theorizing: Issues, implications and responses,’ Journal of International Women’s Studies, 19(2), pp. 186-196.

What do we know about women in today’s economy? (2020). Web.

Woetzel, J. et al. (2015) How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth. Web.

Wojazer, B. and Woodyatt, A. (2020) Paris mayor mocks fine imposed for hiring too many senior women. Web.

Women in work index (2020). Web.

Yellen, J. L. (2020) The history of women’s work and wages and how it has created success for us all. Web.