Introduction

The glass was widely used in Roman times for different purposes. It exerted a greater influence on the daily life of people during this era than any other period before the Renaissance. It was the preferred material in the making of various vessels, household items, and windows. Glass was also used for aesthetic purposes in interior decorations where it mainly made furniture, ceilings, mosaics, and inlaid wall panels. According to Price (1983), glass vessels existed more than 1500 years before the birth of the Roman Empire, especially in the Hellenistic and classical Greek worlds. The use of glass during these ancient times was rare as the material was mainly applied in luxury products. However, the Roman Empire revolutionized the manufacture of glass vessels through glassblowing. Even though glassmakers during the Roman Empire did not invent the technique, they perfected it and expanded the glass market by opening new frontiers in business. This paper discusses the technique of glassblowing during the times of the Roman Empire. It starts by giving a brief history of glassblowing before Italians could learn and hone the skill.

A Brief History of Glassblowing

The history of glassblowing is scanty, and it may be difficult to establish how the technique was discovered or invented. However, historians seem to agree that this technique was invented along the Syro-Palestinian coast where archeological evidence of blown glass has been found (Lightfoot, 2015; Price, 1983; Stern, 1999; Grose, 1977). According to Pliny, a Roman historian, “glassblowing (flatu figure, shaping by breath) was formerly a specialty of Sidon (modern Saida, in southern Lebanon)” (Stern, 1999, p. 443). However, despite the lack of clarity concerning the invention of glassblowing, historians have come up with hypotheses to explain why the technique was necessary together with why and how it spread to other regions, especially into the Roman Empire. According to Lightfoot (2015), during the Classical (ca. 480-323 B.C) and Hellenistic (ca. 323-31 B.C.) periods, glassmakers used time-consuming techniques to make luxurious glass vessels. Therefore, from the modern business perspective one would argue that the inventors of this technique wanted a faster way of manufacturing glass vessels, and thus make the products more affordable.

However, Lightfoot (2015) argues that glassmakers wanted a sophisticated method to produce glass in mass volumes to compete against pottery in the tableware and container market. Such an invention would reduce the time taken to make items, thus minimize the production cost and increase output. The pottery business flourished during the first century, and thus glassmakers wanted to claim their share of this rapidly growing market. Glassblowing was thus born out of necessity, especially among the Roman merchants. This technique spread quickly due to economic, political, and technical reasons. Politically, Augustus’ rule established a vast network of peaceful provinces after ending a century of civil strife in Italy. Therefore, communication from all the corners of the empire became easier. Additionally, Italy’s economy thrived during this time and attracted merchants from Greece and the eastern Mediterranean, and thus glassblowing spread quickly. Finally, the glassblowing technique was inexpensive in terms of the needed materials, which means that a large number of glassmakers could use it (Stern, 1999). Therefore, even though the technique was invented many years before the establishment of the Roman Empire, it was perfected in Italy.

Glassblowing in the Roman Empire

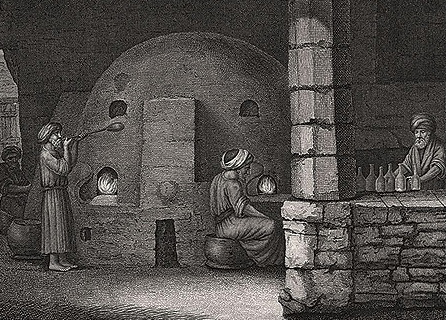

Before the widespread use of glassblowing, ancient Romans made glass by mixing soda and silica. Normally, silica is sand made of quartz, and soda was used to melt it at low temperatures (Grose, 1977). To stabilize the process and give it the desired color, lime or magnesia and colorants would be added to the mixture, respectively. The glass so produced was heavily colored and non-translucent. However, Roman glassmakers started using glassblowing. In this technique, the air is blown directly into the molten glass through a blowpipe to make the mixture bubble (Fig. 1). Such glass would be inflated, thinner, and viscous, thus making it easy to work on and mold into different desired shapes. Stern (1999) posits, “The invention of the blowpipe meant that hollow objects and vessels that previously required labor-intensive operations6 could now be made much more quickly and that less glass per object” (p. 442). Within half a century, glassblowing was an empire-wide technique having started in places, such as Saintes, Lyon, and Avenches.

The perfecting of the technique in Italy meant that high-quality glass was produced to outperform other glasses made in places such as Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean. Glass made in Italy had a wide variety of shapes, diverse functionalities, and it could be used for different esthetic purposes. In Egypt, glassmakers started using glassblowing during Pharaonic times. However, artists were slow to pursue this technique. One of the reasons for such slow adoption of the new technique in Egypt is that glassmaking in the region was considered as art, while in the Roman Empire it was a craft. Therefore, Egyptian artists focused on the slow process of making glassware for luxury and cultural purposes (Stern, 1999). On the other hand, Roman merchants were business-minded, and they wanted to claim a share of the expanding tableware and containers market, which had been dominated by pottery.

The prominence of glassblowing in the Roman Empire was boosted when many Sidonian glassblowers moved to Italy and established businesses in strategic locations such as Campania, Rome, and Aquileia. According to Stern (1999), archeological evidence shows many glass skyphos-handles stamped with Sidonian names, which is a confirmation of their presence in Rome at the time. Before 7 B.C., “many improvements in the glass industry were taking place in Rome both with respect to the coloring of glass and to facilitate production techniques, for example for making colorless glass resembling rock crystal (krystallophanes)” (Stern, 1999, p. 444). By the end of the first century, glassblowing had popularized glassmaking and made glassware fashionable and popular. This trend increased the demand for glass significantly, which means the production of raw glass also grew in tandem, thus advancing the glassblowing technique.

According to Strabo, a Greek geographer, and historian, during the early decades of the first century, “in Rome, it was possible to purchase a glass bowl or small drinking cup for the price of a bronze coin” (Lightfoot, 2015, p. 104). Glassblowing also led to the creation of the first window glass especially after the advancement of furnace technology. Lightfoot (2015) notes that Roman houses had holes drilled through the walls to act as windows before the first century. However, houses started having windows with glass panes after Augustus ended the civil war in Italy during the first century. Glassblowing also gained popularity around the same time, which links the technique to the production of window glasses.

Advancement of Glassblowing in the Roman Empire

Most of the available descriptions concerning glassblowing work on the assumption that the technique required simple tools and basic craft. As such, the technique may not have required further development. Such assumptions existed even in the late 20th century. As recent as 1987, a renowned historian in glass matters, de Donald B. Harden claimed that a “glassblower blows and finishes a vessel using processes that have never altered, at least in principle, since glassblowing originated” (Harden, 1987, p. 87). However, this description was based

Exclusively on 20th-century European practice: a gob of molten glass is gathered on an iron blowpipe about 3-5 ft. long and expanded by blowing. A solid iron rod (also known as a punty or pontil) about 2.5- 3.5 ft. long is affixed to the bottom of the vessel with a wad of glass; the vessel is separated from the blowpipe and held on the punty while the mouth of the vessel is finished (Stern, 1999, p. 444).

Harden (1987) did not offer historical or archeological evidence to prove his claims concerning the simplicity of the glassblowing technique. Stern (1999) disagrees with Harden’s observations based on her experience as a glassblower and evidence from ancient vessels. She argues that the tools that Harden mentions in his claim did not exist when commercial glassblowing started in the first century, especially considering primitive glass furnaces and ancient glassblowing tools (Stern, 1999). This assertion implies that tools for glassblowing were developed further during the commercialization of the technique in the Roman Empire. For instance, the glassblowing bench that Harden mentions in his account did not exist at the time until its invention in the 17th century. Therefore, it cannot be argued that the technique did not evolve or develop further in light of this information.

Additionally, based on the most ancient idiosyncrasies of Roman glass vessels, it is clear that iron shears were probably missing during this period. Similarly, archeological evidence does not show iron tubes for glassblowing. Ceramic blowpipes were the preferred tools for glassblowing during this period. Moreover, sometimes in the second half of the first century, the production of molten glass started, but ceramic blowpipes could not be used in this case. This aspect underscores the need for the invention of iron blowpipes out of this necessity. Therefore, it suffices to argue that glassblowing evolved over time with the invention of new tools that were needed for the technique to be successful.

The Discovery of Molten Glass and Recycling

With the advancement of glassblowing and furnace designs, Roman glassmakers made another significant invention – molten glass. At the same time, glassmakers discovered that broken glass artifacts could be re-melted and reused for different purposes, hence the concept of recycling. According to Stern (1999), the concept of glass recycling existed before the invention of molten glass, but in a different form rather than re-melting. The initial concept of recycling involved the reusing of parts of the broken precious colored pieces, such as gold glass for decoration and mosaic work. According to the available literature, re-melting glass was discovered in the early Flavian period (A.D. 70) (Stern, 1999). This discovery led to the widespread and deliberate collecting of broken glass vessels. Blowing molten glass required high temperatures ranging from 1050-1150oC. Even though the sophistication of Roman furnaces is poorly documented, their capacity to produce high temperatures could be inferred based on the quality of vessels that were produced. Compared to the ancient eastern Mediterranean vessels, which were produced using primitive furnaces, Roman vessels were of higher quality, and this aspect indicates furnaces with the capacity to emit heat at high temperatures.

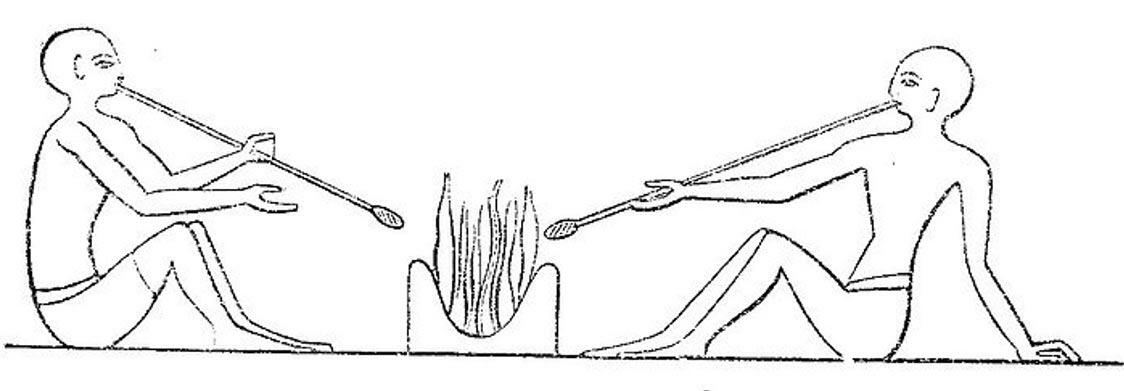

However, despite the discovery of molten glass, most glassmakers in the Roman Empire could not meet the requirements of using the technology, including generating high temperatures. Therefore, they would use simple firepots to soften preheated pieces of glass. One of the problems with re-melted molten glass was that it contained impurities coupled with being multicolored due to the different broken pieces used for the process. Molten glass could also stick to heating crucibles, and thus a significant amount would be lost. Moreover, the process was unpopular among bead makers, as they needed different colors in small amounts. As such, melting colored broken or raw glass in small amounts using open fires was more economical than using crucibles and large furnaces (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, despite these shortcomings, glassblowing was significantly used with molten glass because it was fast and vessels could be produced in large volumes.

The Glassblowers

The available literature has little information concerning Roman glassblowers. However, evidence suggests that the majority of glassblowers were men, even though information concerning their names and socio-economic status is missing. Nevertheless, some women glassblowers from the first century are known. For instance, Sentia Secunda operated a shop in Aquileia, while Neikais worked with other glassblowers in the eastern Mediterranean (Stern, 1999). Two individuals were prominent as glassblowers in the Roman Empire. The first one was known by the name Trellis, while the second one, perhaps his assistant, was called Athenio. This information has been obtained through archeological evidence where the names are inscribed on Roman pottery lamp (Stern, 1999). Ennion was a prominent glassblower in the eastern Mediterranean, where he specialized in mold-blown tableware. According to Lightfoot (2015), Ennion

Did not want to flood the market with cheap glass containers. Rather, he set up his workshop, probably in Sidon, Lebanon, in the first decades of the first century A.D., in order to compete with the local glass industry that was already producing cast tableware. His surviving signed vessels show that he strove to produce quality blown glass that was attractive yet affordable. He put his name on the molds, clearly wanting customers to recognize them as his. He was, so far as is known, the first maker of glassware to do so (p. 105).

Even though Ennion was not from the Roman Empire, he has been included in this paper due to his notable contribution to glassblowing. By the second and third centuries, Roman glassblowers were economically successful enough to be taxed by Emperor Alexander Severus (Stern, 1999). Additionally, epigraphical evidence shows that glassblowers moved freely across the empire to set shop wherever they pleased. Details concerning the organization of the glass industry in the Roman Empire are discussed in the next section.

Commerce and Trade

The glass industry in the Roman Empire was divided into glassmaking and glassworking. Glassmaking occurred in primary workshops where raw materials were converted into glass. On the other hand, glassworking was carried out in secondary workshops whereby glass was molded into the desired shapes. The primary workshops were mainly located along with the coastal areas due to the presence of abundant raw materials (sand). In the west of the empire, Romans were highly organized, and they had advanced business skills as opposed to individuals from areas annexed into provinces during the rule of Augustus. Freedmen and slaves from the annexed regions mainly carried out glassmaking. In business terms, while it is clear that glassblowing produced a wide range of household goods, information is lacking on how business was executed in terms of distribution and retailing. The earliest recording of prices of glass in the Roman Empire was found in the Diocletian’s Price Edict, which was commonly referred to as the PE (Stern, 1999). The PE set the maximum prices of products across the Roman Empire. However, such prices were not fixed, and thus trading of glass certainly depended on supply and demand in different regions.

The manufacture and distribution of glassware, specifically household goods, was done locally in different parts of Italy. For instance, the commercial production of glass tableware peaked during the first century. Independent glassblowers would produce glassware items and sell them in their small workshops to the local community. However, glassware products were also distributed through local shops for retailing. Roman merchants also started buying and selling glassware items both locally and nationwide. Drugstores would sell glass vessels filled with scents and medicinal herbs. Long-distance traders were also common among the Romans. The preferred goods of trade among long-distance traders were raw glass and fine tableware. Goods were mainly transported by sea shipping because it was cheaper than using land means. While fine tableware and other assorted glassware were produced and sold to the masses for household use, raw glass was designated to particular workshops that specialized in the production of luxury glass products. Therefore, glassblowing in the Roman Empire paved the way for the expansion of glass trade within and outside the empire.

Conclusion

The perfecting of glassblowing during the Roman Empire heralded the commercialization of the glass trade starting from the first century. When Augustus ended a century-long war and annexed provinces to establish the Roman Empire, glassblowers enjoyed a peaceful environment to advance their craft. The Roman glassblowing was born out of the necessity to produce glass in large volumes to compete with the thriving pottery industry, which dominated the tableware and containers market. The advancement of glassblowing meant that the cost of producing glassware reduced significantly, and thus glass products became affordable and popular. The technique also facilitated the creation of window glasses during the first century. Glassblowing evolved and advanced with time even though clear records on how this process took place are missing from the current literature.

The technique of glassblowing during the Roman Empire continued to develop with the discovery of molten glass and the recycling of broken glassware. However, information concerning Roman glassblowers is scanty. Males dominated the profession, even though the names of some women who engaged in the business are available. Glassblowers were economically successful to the extent of being taxed towards the end of the third century. The structure of the glass industry was divided into primary and secondary workshops where the raw glass was manufactured and shaped into different forms respectively. The technique of glassblowing was perfected in Italy during the Roman Empire, and it contributed significantly to the commercialization of the glass trade.

Appendix: Glassblowing Techniques

References

A brief history of glassmaking. (n.d.). Web.

Glass through the ages. (n.d.). Web.

Grose, D. F. (1977). Early blown glass: The western evidence. Journal of Glass Studies, 19, 9-29.

Harden, D. B. (1987). Glass of the Caesars. Milan, Italy: Olivetti.

Lightfoot, C. S. (2015). Ennion, master of Roman glass: Further thoughts. Metropolitan Museum Journal, 50, 102-113.

Price, J. (1983). Glass. In M. Henig (Ed.), A handbook of Roman art: A comprehensive survey of all the arts of the Roman world (pp. 205-219). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Stern, E. M. (1999). Roman glassblowing in a cultural context. American Journal of Archaeology, 103(3), 441- 484.