Obesity is a disease that leads to other killer diseases. America must face it as a dangerous foe in the twenty-first century. These are facts and no exaggeration.

What are the other facts?

America is an advanced nation, a leader of the world, economically, politically, and as a nation it is leading the world in terms of ideas and philosophies.

I’ve been trying to ask the following questions that need no answers:

- Is it not that America is “the land of milk and honey” that replaced Israel of the Bible?

- Is it not that Americans are well-fed and well-nourished, living in attractive and affordable houses with clean water and milk and good sewage systems, and are free from the scourges suffered by the rest of the developing world such as malaria, yellow fever, rheumatic fever, blindness due to parasites, and malnutrition?

But Americans have a health problem; mostly are obese and have high rates of heart disease, cancer, and strokes. Obesity is not just a state of the physical body; it is a disease associated with several chronic diseases like cancer, stroke, and diabetes.

Too much energy for Americans? No, it’s an energy imbalance. Energy intake is greater than energy expenditure. That is the simplest definition of obesity.

Statistics from government agencies and the private sector are staggering: one American dies every ninety seconds from obesity-related problems (Burd-Sharps et al., 2008, p. 64); 280,000 Americans die of overweight or obesity-related deaths every year (Allison et al., 1999). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for the first time in history, there are more overweight and obese people in the nation than people of normal weight. An estimated 61 percent of U.S. adults are either overweight or obese.

Our entire nation must be alarmed, gather all possible remedies, urge government agencies and all health workers and organizations to focus their resources to combat this growing disease. It is not just an existing malady; it is growing and growing, and our children and women are the most vulnerable.

Obesity is linked with type-2 diabetes, hypertension leading to stroke coronary heart disease, and several types of cancer. All these have high percent of mortality. What is more alarming is that controlling obesity and its underlying diseases costs billions of dollars for the government. It is estimated that the government spends $110 billion a year, equivalent to 1 percent of the U.S. Gross Domestic Product, just to control or, at least, inform the public about it. (Burd-Sharps et al., 2008, p. 64)

And here’s a sad note: a great percent of the children’s population is succumbing to the disease. There is another alarming fact revealed by scientists: FTO, a gene variant recently discovered by research centres across the UK, is found to be present in a great percent of the population that can lead people to obesity or overweight. (Bradley, 2007)

What really is obesity? Is it just fatness or a result of overeating? Some definitions have to be provided.

Obesity is defined as an excessive amount of adipose tissue in the body; while overweight is defined as excessive weight for a given height and stature (Billum 1987: 866, cited in Bailey, 2006, p. 23). The pathology of obesity is that it lies in the increased size and number of fat cells. An anatomic classification of obesity from which a pathologic classification arises is based on the number of adipocytes, on the regional distribution of body fat, or on the characteristics of localized fat deposits.

Measuring Body Mass Index is the best way of determining whether one is overweight. The American Medical Association considers one overweight when he/she has a body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 29.9. Obesity is divided into mild (BMI of 30 to 34.9), moderate (BMI of 35 to 39.9), and severe / extreme (BMI ≥ 40) classifications (Kushner, 2003, qtd. in Paharia and Kase, 2008).

People with a weight control problem have a real and identifiable physiological and medical condition. Obese people have shorter lives than non-obese people.

Moreover, concern has been growing over the increasing incidence of type 2 diabetes in childhood and among teenagers, attributable to inactivity and increasing obesity levels in childhood. Early appearance of type-2 diabetes appears to be a growing problem, particularly among minority groups in the United States.

Risk factors that contribute to diabetes include modern lifestyle, including inactivity and obesity. These are associated with insulin resistance, lipid disorders, hypertension, and vascular disease.

But obesity is preventable like cigarette smoking if drastic actions are undertaken. The increased prevalence of obesity is a major public health concern because it causes other diseases with high mortality. In the article, “A Potential Decline in Life Expectancy in the United States in the 21st Century,” researchers stipulated that if the prevalence of obesity continues to rise, especially at younger ages, the negative effect on health and longevity in the coming decades could be much worse.

Some major causes for obesity are easily attained, out there in the streets. Food is cheaper in America, particularly high-fat foods. There are also changes in the nature of work, time pressures in our daily living due to the rapid evolution of two- and single-parent families, who often rely on quick, convenient food preparation or takeout.

Women are more susceptible to obesity, especially those belonging to lower socioeconomic status. Women also suffer economic harm due to obesity; this is because they become more inactive as their body mass grow. Census shows that in poor Latino families, those living below the poverty line keep their children indoor for fear of neighborhood violence, giving way to inactivity among the young.

The etiology of obesity is a cumulatively greater energy intake than is needed for daily activities. The excess energy is stored in the form of fat, carbohydrate, or protein. The pathology is enlarged fat cells. The extent to which these enlarged cells produce detrimental health consequences depends on two major factors. The first is the mass of fat, which leads to changes in body configuration and resulting reactions (e.g. stigma, osteoarthritis, or sleep apnea). The second is the location of the fat cells. The principal detrimental metabolic consequences occur when fat cells enlarge.

Some examples of interventions listed by Lobstein (2008) for the different social and economic contexts which have been designed to tackle obesity or to encourage healthy body weight in child populations and which include control groups and have received some degree of scientific evaluation of their effectiveness, include:

- School-home program to enrich the opportunities for physical activity, for 11-year old urban children;

- School-based series of interventions on nutrition and physical activity.

Lobstein (2008) says that these examples can be implemented with great results for the prevention of obesity and overweight.

This chapter from the book, Handbook of Obesity: Clinical Applications, by G. A. Bray and C. Bouchard (pp. 131-150), stresses the importance of focusing on childhood obesity. Lobstein (2008) provides two reasons for this:

- Lifestyle patterns are learned at an early age, and unhealthy patterns can lead to a lifetime of increased risk of ill-health; and

- The pathological effects of obesity are in many cases a product of the time the individual has been obese as well as the severity of the obesity.

This meant that it is important to treat obesity while it is still beginning to grow; the root of the problem is not so difficult to treat. The point of Lobstein (2008) is prevention, which of course is better than cure, as we all know.

Interventions that can maintain or improve health behavior from an early age and that prevent long-term obesity are likely to be far more cost-effective over the longer period than managing and treating obesity and obesity-related diseases after they have developed.

Lobstein (2008) reasoned out that multiple actions in school for the children can have a sustainable beneficial impact than single actions. It can be assumed that the more an environment is consistently able to promote healthy behavior, the greater the likelihood that such behavior will occur. In schools, we can help in instilling awareness on the children, and this can continue in their homes and as they grow up.

Interventions that can be controlled can be done in schools where specific inputs can be measured and the experimental designs can ensure a degree of scientific validity to the results. The focus on the school creates a strong “setting bias” in the scientific evidence.

WHO recommends population-based interventions and to tackle the determinants of food choices and physical activity levels. There is also the need to institute clear nutritional food labeling, and this must be done as a policy.

There is also the concept of investment paradigm where prevention initiatives are considered speculative ventures. An investment portfolio should carry a mixture of “safe” low-return initiatives and “risky” potentially high-return initiatives.

There are reasons why we should prevent obesity occurring in childhood or as a result of behaviors learned in childhood. Policy-makers are sensitive to prevention of obesity in children because children are generally not held responsible for their own health behavior, their behavior is assumed to be more open to influence than that of adults, and they can be more readily targeted than adults, for example, in school settings. Perhaps as a result of this perceived set of advantages, funding for research into childhood obesity prevention tends to be more easily obtained and the evidence base has consequently grown more rapidly.

There is strong evidence and data are available that obesity is prevalent among school-age children and this is rising in virtually all countries of the world. An obese child faces a lifetime of increased risk of various diseases. A child is also likely to experience excess bodyweight as a cause of psychological distress.

Prevention of obesity is preferred for the children because once they are overweight, successful weight loss is difficult to achieve. This is the main point of this essay of Lobstein (2008).

We have to shift focus because of the unavailability of more treatment options for pediatric services.

Lobstein (2008) stresses the classical framework for the development of health promotion strategies which is one that describes interventions in terms of “target groups”, the children for example. The target groups that we can discuss can be specified through reference to the life course, and this starts with the maternal health and prenatal nutrition and proceeds through pregnancy outcomes, infant nutrition preschool and school-age children, adolescents, adults of reproductive age, and older people. WHO also recommends that this can be crosscut with gender and socioeconomic groupings, including racial and ethnic groups, migrant status, income and educational levels.

A limitation to the use of this analysis for identifying target groups is that it can be interpreted to mean that interventions should only act upon the group whose health is in question, for example, those for home improvement in diet or physical activity would be beneficial. This may be considered too narrow a target for tackling obesity as it does not consider how to tackle the determinants of individual behavior.

Lobstein (2008) argue that some interventions are designed to change dietary patterns while others are designed to increase physical activity, or decrease sedentary behavior, in order to increase energy expenditure. Many interventions are designed to tackle both energy intake and energy expenditure in a combined program.

The paper focuses on prevention of obesity in adulthood. It recognizes that overweight and obesity are a world pandemic, widespread and advanced that few regions of the world appear to have escaped its effects. While the essay focuses on obesity prevention in adults, it recognizes the fact that priority should be given to the prevention of obesity and weight maintenance in preference to weight loss interventions.

The authors recognize the need for addressing obesity as early as possible which justifies vigorous intervention in children. But the prevention of overweight and obesity in adulthood should not be neglected. The importance of adult interventions have been reinforced by a new analysis which models the potential gains that might occur if children or adult prevention are the primary focus of action.

The paper reasons out that:

- The sharpest increase in the incidence of obesity is in adulthood.

- Adults usually continue to gain weight during adulthood.

- Adult weight gain is almost always fat gain except in athletes in training.

- The relative risks for many diseases associated with obesity decrease with age but the absolute and population-attributable risks for disease increase with age.

- Interventions in children and adolescents need to be maintained for many more years or decades to have a considerable effect on the number of new cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart disease or cancer compared with interventions in older individuals.

- Adults and parents act as role models and have other responsibilities toward the diet and physical activity behaviors of children. Thus, the prevention of obesity in childhood is dependent on the successful engagement of parents.

The paper explains that if the emphasis of obesity prevention efforts are focused solely on children and further deterioration in obesity levels are halted, this would have almost negligible impact on the disease burden over the next 40 years, while interventions that address adults have the potential for a much more profound effect. Preventing weight gain is likely to produce better returns than attempting to achieve population width loss, with the gain achieved by preventing those who are overweight becoming obese only slightly less than that produced by reduction of 4 body mass index (BMI) units in the population BMI.

James and Gill (2008) argue that the modeling of illness shows that the benefits of identifying and focusing preventive efforts on those who are most at risk of developing chronic disease indicates that it is a major mistake to focus only on those younger than 50 years, as immediate benefit comes from addressing those older than 50 years as well.

There is also the evidence discovered from epidemiological studies that the period of early adulthood has now become the new age group that is gaining weight the fastest and thus has the greatest incidence of overweight and obesity. In previous decades, the rate of weight gain began to rise slowly from the early 20s and peaked when in the fifth or sixth decade of life.

In past generations therefore, most adults attained excessive weight late in life only and thus limited the length of time that they were overweight and at increased risk of illness. The rapid development of obesity in young adults resulted in development of chronic diseases such as coronary atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease, diabetes, fertility problems, and quality of life.

The arguments of the paper are further aided by the following facts:

- that the decline in the age in onset of type 2 diabetes has been tied to early weight gain and development of obesity in early adulthood,

- it has been predicted that the current generation may be the first not to outlive their parents.

The paper also stressed the problem of mothers accumulating excess weight and developing obesity during pregnancy. There is considerable variation noted in the amount of weight gained during gestation and this excess weight is often retained after giving birth. Some women experience extreme weight gains and others have cumulative increases in body weight after each pregnancy. And there is the propensity of obese women to produce large babies, and a great possibility for these children to become obese during childhood. Survey results showed that the level of overweight and obesity begins to climb rapidly in early adulthood and reaches its peak in the middle age for both males and females. But the rates of overweight and obesity begin to decline from the seventh decade. These increases in body weight are accompanied by changes in body composition that result in middle-aged and older adults having a higher level of body fatness for any level of BMI when compared with younger adults.

There is also the detrimental consequence of aging on the development of obesity-related illness which is the increase in central distribution of body fat that occurs in both men and women with age. Likewise, adults have the tendency to develop abdominal obesity, which is now linked to an enhanced risk of comorbidities and is a key feature of a particular malady known as syndrome X or the metabolic syndrome. This is characterized by a relative excess of abdominal fat, hypertension, insulin resistance with glucose intolerance or diabetes, dyslipidemia, and micropretenuria. Men have have higher proportion of body fat stored centrally than women, and the level of abdominal fat increases gradually with age. Women generally enter the middle years with a lower level of abdominal fat but it begins to accumulate rapidly within this period so that by the seventh decade of life, men and women have a more equal distribution of body fat. Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-based working group reaffirmed the importance of addressing abdominal obesity.

In our second source, the authors recognize the fact that no country, no matter how wealthy, has unlimited resources to apply to health care, and this applies even to the United States. However, with limited resources, countries should be able to make decisions about where to target interventions.

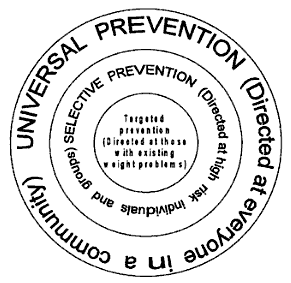

The essay suggests a follow up of the report of the WHO Consultation on obesity which states that there are three different but equally valid and complementary levels of obesity prevention. These are shown in the figure below.

In the figure above, the inner circle represents the target prevention which is aimed at those with an existing weight problem, while the second ring represents the selective approach directed at high-risk individuals and groups. The broad outside ring represents universal or public health prevention approaches, which are directed at all members of the community.

The logical approach is to consider identifying those who are on the borderline of obesity, or adults with BMIs of perhaps 28 to 29 kg/m2 and attempt to prevent them from gaining further weight and thus entering the obese category. Success would relate to maintaining a maximum BMI of 29 kg/m2 for individual adults.

The essay provides reasons for focusing on Weight Gain Prevention in adults, and these are:

- Weight gain adulthood carries an independent risk of ill health

- Risk for chronic disease beings to increase from low BMI levels and significant weight gain can occur within normal limits.

- Extended periods of weight gain are difficult to reverse.

- Weight gain in adulthood is mostly fat gain.

- A focus on weight gain prevention avoids exacerbation of inappropriate dieting behaviors.

- The message is equally relevant to all sections of the adult population.

- It avoids further stigmatization of people with an existing weight problem.

- It avoids reference to poorly understood terms such as “healthy weight”.

The authors concluded that weight gain prevention is important in adults, and more effort should be applied to find successful intervention to achieve this outcome. Current obesity prevention efforts in adults have been limited and may have been inhibited by a number of factors including a lack of acceptance of the importance of obesity as a serious health problem, the setting of inappropriate or unachievable goals, a lack of focus on weight gain prevention as the main outcome, a poor understanding of effective prevention strategies, underfunding of public health and obesity prevention research, problems identifying and targeting at risk individuals and groups, and inadequate public health and practical prevention skills within the health workforce. Determining the most effective strategies for the prevention of obesity at the community level must be seen as a priority.

Discussion

There are many possible solutions to the question: What is the best way to address obesity in the United States? In fact all of the above facts and recommendations are possible solutions. What is only needed is a systematic approach and policy formulation that should come from the government in order for these solutions to become a way of life and something that should be followed by our children and adults.

For example, we can avoid the risk factors that contribute to diabetes from childhood up to adulthood. This we can do while at school and at home. We have to apply what we learn at school in our lifestyle.

We can focus on diet and exercise. Our two sources above state of interventions and policies that can be instituted by the government or health professionals and workers.

The best recommendations of diet, exercise, and enough sleep should be a part of our daily lives. Not only diabetics and obese people can do it but also everyone. In other words, everyone must have a change of attitude – from inactivity or full dependence on technology and robots to active lifestyle, full of energy and efforts to combat the disease.

Dies and exercise are two simple but effective solutions to the problem of obesity and overweight. This can be a part of the daily programs at school and at school. All the other sources that we have browsed and consulted point to diet and proper nutrition and exercise.

Conclusion

In the two sources mentioned in the early part of this paper, we discussed early intervention on children and later adult intervention on obesity and overweight. Both approaches and recommendations are commendable and can lead to controlled obesity and overweight. But the second source which recommended a focus on adult intervention has some greater points.

Indeed, we cannot leave behind our children. In school, it is of great importance that they learn how to control themselves in over-eating or taking in energy without much mobility as they are so engrossed with computers and other indoor activities. But adult diabetes and overweight is much more difficult to deal with. Therefore, this has to be given enough time and efforts. Policies of the government should be more geared for prevention and cure in adult overweight and obesity.

As mentioned, obesity is preventable like cigarette smoking. Policies and programs of the government which have been provided enough funding should be more geared to controlling this.

As to the policies for recommendation, Lobstein’s is more liberal in that the recommendations are focused on diet and physical activity. This can be applied on both children and adult, in school and at home, and in our daily lives. Offices and workplace, businesses and organizations can be more focused on prevention of obesity and overweight problems.

References

Allison DB, Fontaine KR, et al. Annual Deaths Attributable to Obesity in the United States. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1530-1538.

Bailey, E. J., 2006. Food choice and obesity in black America: creating a new cultural diet. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

Bradley, D., 2007. Obesity Gene. Web.

Burd-Sharps, S., Lewis, K., and Martins, E. B., 2008. The measure of America: American human development report. United States of America: Columbia University Press.

Church, T., 2008. Exercise and weight management. In G. A. Bray and C. Bouchard (Eds.), Handbook of obesity: Clinical applications (third edition) (pp. 291). New York: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc.

Farooqi, I. S. & O’Rahilly, S., 2008. Genetic evaluation of obese patients. In G. A. Bray and C. Bouchard (Eds.), Handbook of obesity: Clinical applications third edition (pp. 45-52). New York: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc.

James, W. P. T & T. P. Gill, T. P., 2008. Prevention of obesity. In G. A. Bray and C. Bouchard (Eds.), Handbook of obesity: Clinical applications third edition (pp. 157-170). New York: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc.

Lobstein, T., 2008. The prevention of obesity in childhood and adolescence. In G. A. Bray and C. Bouchard (Eds.), Handbook of obesity: Clinical applications (third edition) (pp. 131-150). New York: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc.

Paharia, M. I. and Kase, L. (2008). Obesity. In B. A. Boyer and M. I. Paharia (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of clinical health psychology, pp. 81-83. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.