Abstract

Inattentional blindness defines the inability to detect externally apparent details of the overall context while focusing attention on individual objects. This effect can be life-threatening and create adverse consequences, especially in relation to crisis situations where maximum attention is required. In the present dissertation work, an experimental method was used to test the effects of inattentional blindness on the unconscious perception of information. The results demonstrated that unconscious perception does not exist or appears to be very insignificant in inattentional blindness. This is consistent with many academic papers and allows the results to be assessed as reliable and valuable.

Introduction

The mechanisms of perceptual processing of human consciousness are the subject of extensive research aimed at identifying the essential patterns that determine how an individual perceives objective reality. Academic interest in this problem is primarily motivated by applied needs, as a thorough understanding of these mechanisms can optimise community functioning and minimise inattentional errors. With respect to the study of perceptual processing, a phenomenon associated with inattentional blindness or, as it is often called, perceptual blindness has been identified (Mack & Rock, 2000; Othman & Laswad, 2019). Strictly speaking, this effect occurs when one is unable to effectively perceive reality in the absence of fixation of attention — in simple terms, the individual misses specific details from observation if they are not focused on them. It is noteworthy that inattentional blindness is formed solely by psychological patterns of brain activity and is not determined by visual impairment or other physical limitations. The existence of this phenomenon creates a need for a thorough scientific study of the meaning of perceptual blindness and the conditions under which it can occur and be inhibited. In this dissertation work, inattentional blindness is studied using two levels of the independent variable, allowing us to assess how important attention is for learning reality and whether unconscious processing of stimuli exists in light of inattentional blindness.

Perceptual blindness is not an unambiguous effect leading to universal results. It is well known that the phenomenon can be used for entertainment and hedonistic purposes, where the illusionist tricks the audience’s consciousness by fixing their attention on particular details (Camí & Martínez, 2022). On the other hand, inattentional blindness can cause criminal and fatal outcomes (Mack, 2003). Studies show that this effect often causes traffic accidents because the driver’s attention is distracted and not focused on all details of the traffic situation (Papantoniou et al., 2019). Furthermore, similar to illusionist techniques, pickpocket thieves and crooks can exploit an individual’s perceptual blindness for selfish purposes. An interesting example in terms of the topic under investigation is the experiment with the pilots of the Boeing 727, who tested a new technology to project flight data directly onto the windshield (Chabris & Simons, 2010). The logic behind such technology intuitively follows from the assumption that fixing attention on the windshield reduces the likelihood of landing accidents by keeping pilots focused on the runway. However, Chabris and Simons showed that simulation test results, in this case, resulted in a collision with a parked aircraft because the pilots, while focusing on the flight data being broadcast, did not detect the apparent details in front of them. All of these outcomes, whether favourable or unfavourable, are realised based on an individual’s inability to discern an unexpectedly occurring stimulus in the field. In fact, most people are under the false impression that they are capable of scrutinising reality as it is and do so simply by opening their eyes and looking. However, there is growing evidence in academic discourse that people can look without seeing and see things that are not really there (Mack & Rock, 2000). Recognising that the phenomenon of inattentional blindness exists, researchers have begun to question precisely how attention and individual consciousness may be related — this has spawned a wave of new work examining this association (de Pontes Nobre et al., 2020). In their study, Mack and Rock concluded that inattentional blindness occurs in the face of unobserved apparent stimuli if they are introduced unexpectedly and without a focus of attention. The examples of the accident and illusionist in the previous paragraphs perfectly illustrate the practical application of such inattention. Consequently, conscious perception can only be formed when attention is present (Mack & Rock, 2000). This naturally leads to the conclusion that attention is the critical pattern that shapes the visual perception of reality and allows for fewer cognitive errors.

The idea that such an effect exists has long been suggested, and a literature search on Google Scholar suggests topical material dating back to the late nineteenth century. Although the term ‘Inattentional Blindness’ is found in earlier works, the conceptualisation of the concept was realised by researchers Mack and Rock in 1992 (Duggal & Arora, 2019). With the intensification of globalisation processes and the inclusion of more scholars in collaborative work, the problem of inattentional blindness has gained particular popularity in academic discourse in recent decades. Chrestomathic, in this sense, is the gorilla experiment that perfectly demonstrates the impossibility of carefully perceiving reality without focusing attention, first described in Chabris and Simons (2010). Specifically, in this experiment, a group of respondents were asked to count the number of times players wearing white T-shirts passed a basketball, as shown in Figure 1: most respondents were focused on counting in a dynamic game and did not notice a woman dressed as a gorilla walking across the playing field. With this trick, the researchers were able to show that visual perception of reality is unattainable without attention, which means that unexpectedly appearing details may not be noticed.

A deeper understanding of the reasons for the development of such behaviour leads to an understanding of the existence of specific cognitive schemata that govern an individual’s perception. Specifically, psychological schemas should be referred to as this defined and unique body of knowledge that incorporates past experiences on a particular topic to process and interpret incoming information (Flemisch et al., 2019). The existence of such schemas is mediated by the multiplicity of the information field combined with limited cognitive-perceptual abilities. It turns out that schemas form some deductive prototype of objective reality, optimising the possibilities for learning and saving the individual’s cognitive resources when processing new information (Jian et al., 2019; Mack, 2003). The concept of schemas was developed by the Swiss psychologist Piaget: according to Piaget, schemas are able to form with the learning of new experiences and reorganise when knowledge contradicts it (Pascual-Leone & Johnson, 2021). Examples of such cognitive schemata can easily be found in everyday practice — more specifically, this includes thinking and perceptual stereotypes, although it is not always the case that such research based on schema activity leads to the correct result. With regard to inattentional blindness, the existence of schemata explains the lack of perception in unfocused attention since schemata determine the prediction of a new reality and can form a biased distortion when unexpected stimuli are introduced.

Using the concept of schemas allows the brain to ignore some of the details in reality in order to concentrate cognitive resources sparingly. It turns out that even details of reality that are within the individual’s line of sight are unnoticed and not fully perceived, which creates opportunities for the realisation of inattentional blindness. The effect of reality re-painting can be compared to the classic experiment of showing a respondent a celebrity’s face in the periphery while needing to fixate on a point in the centre of the screen (Tangen et al., 2011; Tatler & Land, 2011). This creates a sense of distorted, grotesque people, which does not correspond to objective reality but reflects the mechanisms of cognitive second-guessing of details outside the focus of attention. In addition, brain sensation overload as a result of severe emotional turmoil must also be considered, in which case the mind becomes fixated on living a particular experience, which prevents attention to exterior details (Wulff & Thomas, 2021). It has also been shown that an individual’s attention works like a selective filter: paying attention to detail allows the mind to better process information about it (Sternberg et al., 2012). The context of detail in relation to the overall scale of observation should also be taken into account. There are two types of changes in reality related to the degree of detail correspondence, namely congruent and incongruent responses (Greve et al., 2019; Liu, 2018). Congruence should be referred to a situation where the details fit into the overall context of reality and are not strictly unexpected to it; a car driving in the oncoming lane is an example of such a change. On the other hand, incongruence is realised through unexpected, inconsistent and contradictory details — the example of the gorilla while playing ball is a perfect illustration of incongruent change. Research shows that inattentional blindness varies depending on the type of change being introduced: for congruent reactions, recognition of unexpected details is faster and more reliable than for incongruent reactions (Liu, 2018). In other words, there is no consensus on what exactly should be considered the cause of the development of inattentional blindness.

It is important to additionally note that individuals’ lack of awareness of the existence of such a phenomenon leads to increased results of inattentional blindness. For this reason, the use of naïve respondents who are unaware of the true purpose of the study is critical to reliable testing (Haug, 2018). However, it is a mistake to assume that inattentional blindness only affects inexperienced individuals; studies have demonstrated that even experienced, trained respondents miss the gorilla in most cases (Drew et al., 2013). There are several conditions under which inattentional blindness can be realised (Pugnaghi et al., 2020). First, the individual’s attention must not be focused on detail during observation but must be focused on a specific point in space, which, among others, may be dynamic. Broadening the scope of attention allows more details of the context to be detected and reduces the likelihood of inattentional blindness (Erol et al., 2018). Second, such details must be entirely within sight in order to satisfy the phenomenon of inattentional blindness. Thirdly, if individuals’ attention has been deliberately shifted to such detail, they must be able to recognise it, which is realised through the use of a pattern of past experiences. Finally, a critical condition is an unexpectedness of introducing change into observation.

It is fair to acknowledge that the relationship between inattentional blindness and conscious perception through the paradigm of unexpected stimuli is not universal and can lead to contradictory results. In particular, reference to Mack and Rock (2000) and Kihlstrom et al. (1992) shows that in patients with cortical damage, implicit perception can occur even in the face of inattentional blindness. The focus on such patients is not coincidental: damage to the cortex leads to impaired visual analysis and thus affects sensory-cognitive abilities (Oude Lohuis et al., 2022). Meanwhile, amnestic syndromes resulting in an impaired recall of past experiences also show a clear link between implicit perception and implicit memory, formed from the use of unconscious past experiences (Mack & Rock, 2000). In this sense, the portion of experience that has been unconsciously accumulated affects the perception of reality, which may contradict the effect of inattentional blindness that requires fixation of attention.

The present dissertation work uses the inattentional blindness paradigm to investigate whether perceptual processing of stimuli without attention can occur, even if they are not consciously noticed. The study is implemented through a trial on a sample of 26 respondents who were invited to participate in a visual pattern experiment. Individuals were asked to complete three tests of whether or not they recognised circles on a computer screen as identical and a control question about the presence of additional stimuli during observation. Differences in the tests were determined by the respondent’s level of awareness of what they were supposed to be observing. The results showed a refutation of the working hypothesis describing the impossibility of the existence of the unconscious perception of information in inattentional blindness.

Objectives and Hypotheses

The aim of this study is to investigate whether unconscious perception without attention exists, as there are still some ambiguities as to whether unconscious perception remains unobserved in light of the existence of the phenomenon of inattentional blindness. The research hypothesis identified for the experiment postulates that unconscious processing of stimuli despite inattentional blindness exists. The proposed experimental design provides answers to the research hypothesis and provides a valuable contribution to the development of knowledge about inattentional blindness.

Method

Research Design

The present dissertation work was built on a quantitative methodological approach paradigm in which key metrics were measured numerically, including the use of quantitative data processing techniques for statistical analysis of the data collected. The quasi-experimental method was used to test the previously postulated hypothesis and aimed to test the statistical significance of differences in the numerical characteristics of the conducted tests. A two-level manipulation of the independent variable, namely the degree of participants’ awareness of the need to focus on the word at the end of each test, allowed the effect on the two dependent factors, which included the report and the results of success in passing the word test, to be assessed. More specifically, the levels of the independent variable included inattention and full attention, which was realised through the amount of information given to them about the last test question. Results were collected directly from respondents, so primary test-taking data were used for analysis. The choice of this quasi-experimental approach was motivated by the excellent fit between the objectives to be measured and the resources available. In particular, studying cognitive patterns is not possible without direct testing on live subjects, and differentiating the independent factor into levels allowed us to assess the importance of focusing attention on the ability to discern unexpected details of observation in light of inattentional blindness.

Participants

University of West London students ranging in age from 18 to 50+ were invited to participate in the experiment. The sample was diverse in terms of gender and ethnicity, thus minimising bias and creating a robust group of participants. The final sample size was 26 people who were motivated by incentives for passing the tests, be it course credit or a prize draw. It is worth clarifying that the participants were naïve about the ultimate aims of the study, as they were informed that the tests were designed to test visual acuity and fluency.

Materials

To take the tests, students were invited to a Paragon laboratory classroom (308), in which computers with SuberLab software pre-installed were arranged. SuberLab offered the students a white screen divided by several bisected circles of different colours — red and green — for the test. The point in the centre of the screen served as the point of initial fixation of attention, but subsequently, the respondent’s attention was deliberately shifted (Mack & Rock, 1999). Four bisected circles appeared at a distance of 6 degrees from this point during testing. During the last (critical) test question, a small word in English appeared at the fixation point, which may or may not have been detected by the respondents. To record the results of the critical question, respondents had to complete a word for which only the first and last letters were known. Passing the word test assessed whether the individuals’ minds could process and remember the word, which was quickly depicted on the screen in the inattention area. SPSS v.25 software pre-installed on University of West London laboratory computers was used for statistical analysis. Test data were processed using appropriate methods and then exported to a WORD document for use in this thesis.

Procedure

To form an experimental sample, invitations were sent to students at the University of West London by email. Participants were not made aware of the purpose of the test in advance but completed an informed consent form and information sheet before starting. The testing took place in a local Paragon computer lab (308), where a group of students used work computers with SuberLab software pre-installed. Each participant sat at a distance of 76 centimetres from the computer screen to increase the reliability of the results.

In the first test, which was based on inattention, participants were asked eleven questions, ten of which were classified as non-critical. During the non-critical questions, a fixation point in the centre of the white screen appeared at 1500 ms, followed by circles of different colours at 200 ms, which were replaced by a masking screen at 500 ms. This strategy concealed the circles shown earlier and inhibited the possibility of image processing (Clarke & Porubanova, 2020). Participants were asked to answer a single dichotomous question after each round about whether the circles shown were the same (S) or not (O). The final test question did the same one, with the difference that in addition to the four circles, a word in English appeared in the centre of the screen for 200 ms. The question after this round asked whether participants noticed anything additional on the screen apart from the circles. In addition, a quick test was used to measure the possibility of unconscious perception, in which participants had to complete the word seen on the screen. At the full attention level, participants were not asked for additional details of the screen after the last question but were immediately asked to complete the words with the missing letters in the middle. This strategy allowed for an assessment of the ability to perceive information without awareness. At the conclusion of the thesis project, the sample participants would be informed and thanked. In addition, a control test without any intervention was conducted in the study to assess the ability of the respondents to guess the correct word. The control test was conducted in a laboratory classroom, where random participants were asked to guess words for which only the first letters were known: Gr_._._. and Fl_._._.

To perform statistical analysis, the results of the success of selecting the circles as equal or not, as well as the results of the critical question and the word completion task, were collected in an Excel table, then imported into SPSS v.25. As the sample size was relatively small, the choice of a non-parametric test was necessary to estimate the results (Moffatt, 2021). As the results of most rounds were measured on a dichotomous nominal scale, the Related-Samples McNemar Change Test, which tests changes for a sample due to manipulation of an independent variable, was used for hypothesis testing (NHS, 2020). The results of this test allowed us to determine the statistical significance of differences between the levels of the independent variable and to confirm or refute the working hypotheses.

This dissertation work was conducted in strict accordance with academic standards of integrity and the pursuit of reliable results. The ethical principles of the University of West London research were used to create a responsible, constructive and acceptable experiment. In addition, as mentioned above, each participant completed an informed consent form, so participation was voluntary. In addition, all references used in the thesis were carefully cited, and no plagiarism was used.

Results

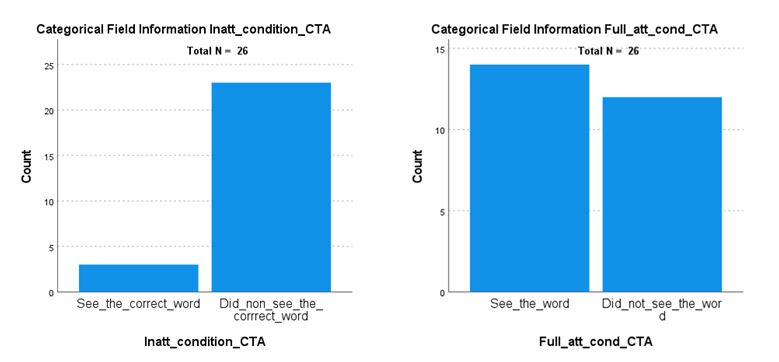

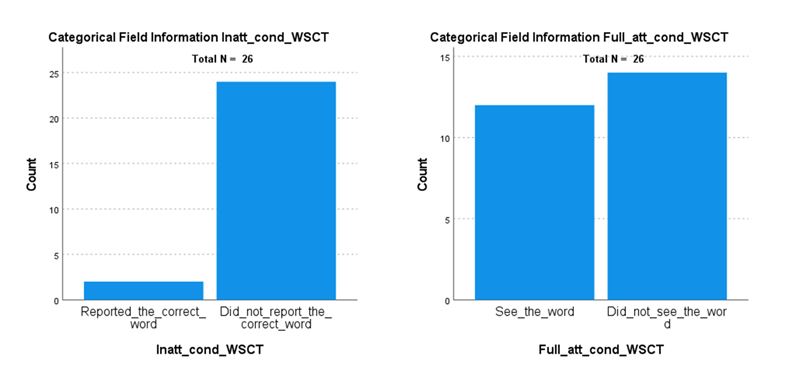

The aim of the present dissertation study was to test the possibility of unconscious attention of individuals to unexpectedly appearing details in the field of vision in the light of inattentional blindness. Using an experimental approach, the aim was to assess the extent to which inattentional blindness affects not only the ability to detect such objects but also their unconscious perception. Manipulating the focus of respondents’ attention allowed us to identify the relationship between detection and perceptual abilities. The results of descriptive frequency statistics showed different trends for the ability to see the word in the critical question rounds among inattention levels and full attention levels. Fig. 2 reports that only 11.5% of respondents (n = 3) reported being able to see the word in the inattentive condition. The same parameter for the full attention level was 53.8% (n = 14), indicating an average of the 4.7-fold difference between the results for the two levels of the independent variable, corresponding to eleven participants moving to the status of respondents who were able to see the word while focusing attention. Fig. 3 shows that with attention focusing, the number of respondents who correctly completed the word increased by 5.5 times the attention level: 46.1% (n = 11) versus 7.7% (n = 2), respectively. For the control variable, only 19.2% (n = 5) of respondents were found to be able to guess an incomplete word, indicating a low probability of blind guessing in the levels of the independent variable.

The results of the non-parametric Related-Samples McNemar Change Test showed statistically significant differences in word detection ability with increasing respondents’ awareness of the gist of the last question, that is, increasing focus of attention. Specifically, the McNemar exact test determined a statistically significant difference as p =.003. For the task in which respondents had to complete the word, statistical significance between the differences was also found as p =.006. In other words, in both cases, the null hypothesis of equal distributions was rejected, meaning that the proportion of participants who saw and correctly recognised the word after focusing attention increased. This may imply that inattentional blindness is an important predictor of unconscious perception, as increased focus on detail leads to reliably higher numbers of detected details and correct responses. No statistical difference was found for control and full attention in the context of the word-completion task, confirming the low probability of guessing a word based on the available letters.

Table 1: Related-Samples McNemar Change Test Results for Different Tests

Discussion

The study tested the hypothesis postulating the existence of unconscious stimulus processing despite inattentional blindness. The results of an experiment with 26 naïve participants demonstrated that attention fixation significantly reduced the proportion of unexpected details detected on the screen and the proportion of correct responses for word completion. In other words, these results show that focusing on individual details can impair unconscious perception but does not completely inhibit it, as a proportion of respondents still noticed and even correctly wrote down the words they saw, despite being inattentively blind.

The experiment confirmed the phenomenon of inattentional blindness, described in many theoretical works. The basic idea of perceptual blindness is that the fixation of attention on individual elements of the overall picture prevents effective perception of the context, leading to distortions, inaccuracies and disregard of details (Mack & Rock, 2000). The results of the study demonstrated the same effect, as inattentive respondents hardly noticed the words, much less were able to recognise them correctly, focusing their attention on the bisexual circles on the screen. More specifically, it was reported that approximately one in two respondents was inattentively blind because they could not complete a word: this data is in excellent agreement with Mack et al. (2016), who report that, on average, 25% to 75% of respondents are inattentively blind. It appears that the conclusion reached by Chabris and Simons (2010) is fully applicable to the results of this study, namely that to look is not to see. In other words, the basic findings from this study fit perfectly into the academic discourse and support common claims.

Meanwhile, the errors resulting from inattentional blindness are determined by a lack of attention to the overall context in the context of focusing on single details. In this case, individuals’ cognitive functions filter out unnecessary information that may not seem necessary at the moment (Jian et al., 2019). The results of the inattention test also showed that excessive focus on circles inhibited the ability to detect words. This allowed respondents’ minds to conserve cognitive resources. It is also worth noting the importance of the effect of stress — the test was conducted under rapid conditions, and respondents had little time to become aware of what they saw. This supports the finding of Wulff and Thomas (2021) that stress is a predictor of inattentional blindness because the emotional function of the brain is excessively focused on a particular task or experience. It is also important to note the unexpectedness with which information appeared on the screen. It was shown that when individuals were suspicious of additional items, the word detection rate increased by a factor of 4.7. Notably, the resulting difference in the proportion of correct responses for the two levels of the independent variable is almost identical to that found in the large Mack & Clarke (2012) trial, suggesting some pattern to this distribution. Consequently, unexpected, non-congruent changes in context increase the likelihood of inattentional blindness (Pugnaghi et al., 2020; Liu, 2018; Drew et al., 2013). Moreover, aware individuals expected to see something extrinsic on the screen, allowing them to increase their attention and thus examine the content more closely (Sternberg et al., 2012; de Pontes Nobre et al., 2021). It is not difficult to draw a parallel with Piaget’s cognitive schemata, according to which participants had formed ideas about the course of the test and the purpose of the study, so they did not expect to see anything additional (Flemisch et al., 2019; Mack, 2003). From this, it can be concluded that awareness is necessary for effective unconscious information processing — otherwise, the individual misses out on details of reality because they do not expect to see them. In other words, in order to get rid of inattentional blindness, one must get rid of a focus on individual details.

An important strand of the detailed discussion in light of academic research is the use of unconscious memory as a predictor of inattentional blindness. As described by Mack (2003), one of the reasons for the formation of this effect is forgetting about an object that has not been given proper attention. In this sense, respondents saw every word on the screen but unconsciously forgot about it as their attention was focused on other tasks. In addition, Mack proposed a structure for a priming test which confirms the functionality of implicit memory. The idea of this test was transferred to the methodology of this study in order to test it on a control group, and the results demonstrated that most respondents were indeed unable to guess the word because they did not see it, whereas respondents at the full attention level were more likely to be able to complete the word, even though they only saw it for 200 ms.

Regarding the hypothesis to be tested, it should be clarified that it postulated the existence of the unconscious perception of information even under conditions of inattentional blindness. This meant that even inattentively blind individuals — which may be the majority, according to Mack et al. (2016) — can unconsciously process incoming information and effectively remember it for use. The experiment that was conducted, however, showed the opposite result. The number of respondents who completed a word correctly in the inattentive condition was statistically significantly lower than the proportion of participants who did the same in the full attention condition. In other words, focusing attention on objects produces inattentional blindness and inhibits unconscious processing of results. This interestingly correlates with the conclusion proposed by Mack et al. (2016) that conscious perception requires attention. In particular, the current dissertation work has shown that unconscious attention does not exist in inattentional blindness, which extends and does not contradict the researchers’ conclusion.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study makes a valuable contribution to the academic discourse on the topic of inattentional blindness and its relationship to unconscious perception. It has the advantage of drawing a statistically significant conclusion about the non-existence of unconscious perceptual information in inattentional blindness, which refutes some of the research (Kihlstrom et al., 1992). The methodological basis of the study was based on the lessons identified by previous authors, which resulted in reliable and valid results. It is also worth noting the value of the chosen method of data collection, namely the trial with respondents — this provided primary data that responded to a real agenda.

However, the study does not exclude some limitations that prevent the results from being extrapolated widely. The small sample size could potentially undermine the internal validity of the trial and increase the bias of the results. In addition, the word shown on the screen was in English, which allows inferences to be made only for the unconscious perception of English-speaking individuals. It is also worth noting that the data cannot be extrapolated to people with colour blindness, as the research method assumed healthy colour vision in the sample.

Areas and Directions for Future Research

Two levels of the independent variable and two levels of dependent factors were used in this dissertation work. Thus, one of the most obvious directions for future research is to expand the number and quality of variables to investigate the relationship more deeply between unconscious perception and inattentional blindness. In addition, the use of a non-English-speaking sample will make it possible to assess the extrapolability of the findings to other cultures and to determine the prevalence of the phenomenon. An important avenue for future research is also to investigate this effect for different gender and age groups, among others, in order to discover potential patterns.

Conclusion

To summarise, the experiment disproves the postulated hypothesis and shows the impossibility of unconscious perception in inattentional blindness. This conclusion has several practical implications. Firstly, it offers a refuting view for some academic work and creates the condition for additional testing of the results on a larger sample. Second, it illustrates the need to reduce the level of focus to inhibit inattentional blindness in order to process more data, especially in crisis situations. Thirdly, it illustrates that filling up working memory leads to a reduction in the capacity to analyse the overall context and therefore creates the need to develop memory offloading practices to minimise this effect.

References

Camí, J., & Martínez, L. M. (2022). The illusionist brain: The neuroscience of magic. Princeton University Press.

Chabris, C., & Simons, D. (2010). The invisible gorilla: And other ways our intuitions deceive us. Harmony.

Clarke, J., & Porubanova, M. (2020). Scene and object violations cause subjective time dilation. Timing & Time Perception, 8(3-4), 279-298. Web.

de Pontes Nobre, A., de Melo, G. M., Gauer, G., & Wagemans, J. (2020). Implicit processing during inattentional blindness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 119, 355-375. Web.

Drew, T., Võ, M. L. H., & Wolfe, J. M. (2013). The invisible gorilla strikes again: Sustained inattentional blindness in expert observers. Psychological Science, 24(9), 1848-1853. Web.

Duggal, R., & Arora, S. (2019). Influence of mental load on inattentional blindness. IAHRW International Journal of Social Sciences Review, 7(5-III), 1681-1684.

Erol, M., Mack, A., & Clarke, J. (2018). Expectation blindness: Seeing a face when there is none. Journal of Vision, 18(10), 1115-1115. Web.

Flemisch, F., Abbink, D., Itoh, M., & Pacaux-Lemoine, M. P. (2019). Special issue on shared and cooperative control. Cognition, Technology & Work, 21(4), 553-554. Web.

Greve, A., Cooper, E., Tibon, R., & Henson, R. N. (2019). Knowledge is power: Prior knowledge aids memory for both congruent and incongruent events, but in different ways. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(2), 325-341. Web.

Haug, M. C. (2018). Fast, cheap, and unethical? The interplay of morality and methodology in crowdsourced survey research. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 9(2), 363-379. Web.

Jian, Z., Zhang, W., Tian, L., Fan, W., & Zhong, Y. (2019). Self-deception reduces cognitive load: The role of involuntary conscious memory impairment. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1-14. Web.

Kihlstrom, J. F., Barnhardt, T. M., & Tataryn, D. J. (1992). The psychological unconscious: Found, lost, and regained. American Psychologist, 47(6), 788–791. Web.

Liu, H. H. (2018). Age-related effects of stimulus type and congruency on inattentional blindness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1-9. Web.

Mack, A. (2003). Inattentional blindness: Looking without seeing. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 180-184. Web.

Mack, A., & Clarke, J. (2012). Gist perception requires attention. Visual Cognition, 20(3), 300-327. Web.

Mack, A., & Rock, I. (1999). Inattentional blindness: An overview by Arien Mack & Irvin Rock. Psyche: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Consciousness, 5, 1-26.

Mack, A., & Rock, I. (2000). Inattentional blindness. MIT Press.

Mack, A., Erol, M., Clarke, J., & Bert, J. (2016). No iconic memory without attention. Consciousness and Cognition, 40, 1-8. Web.

Moffatt, P. G. (2021). Experimetrics: A survey. Foundations and Trends in Econometrics, 11(1-2), 1-152. Web.

NHS. (2020). The analysis of research data [PDF document]. Web.

Othman, R., & Laswad, F. (2019). Future forensic accountants: Developing awareness of perceptual blindness. Journal of Forensic and Investigative Accounting, 11(2), 299-308.

Oude Lohuis, M. N., Pie, J. L., Marchesi, P., Montijn, J. S., de Kock, C. P., Pennartz, C., & Olcese, U. (2022). Multisensory task demands temporally extend the causal requirement for visual cortex in perception. Nature Communications, 13(1), 1-19. Web.

Papantoniou, P., Antoniou, C., Yannis, G., & Pavlou, D. (2019). Which factors affect accident probability at unexpected incidents? A structural equation model approach. Journal of Transportation Safety & Security, 11(5), 544-561. Web.

Pascual-Leone, J., & Johnson, J. M. (2021). The working mind: Meaning and mental attention in human development. MIT Press.

Pugnaghi, G., Memmert, D., & Kreitz, C. (2020). Loads of unconscious processing: The role of perceptual load in processing unattended stimuli during inattentional blindness. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 82(5), 2641-2651. Web.

Simons, D. (2010). Selective attention test. YouTube. Web.

Sternberg, R. J., Sternberg, K., & Mio, J. (2012). Cognitive psychology. Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Tangen, J. M., Murphy, S. C., & Thompson, M. B. (2011). Flashed face distortion effect: Grotesque faces from relative spaces. Perception, 40(5), 628-630. Web.

Tatler, B. W., & Land, M. F. (2011). Vision and the representation of the surroundings in spatial memory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1564), 596-610. Web.

Wulff, A. N., & Thomas, A. K. (2021). The dynamic and fragile nature of eyewitness memory formation: Considering stress and attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1-7. Web.