Introduction

As mobile technologies provide more and more opportunities for travel, the need for travel agencies reduces. Such applications as Google Maps, Foursquare, Booking.com, Airbnb, Tripadvisor, and hundreds of others make independent traveling easier, cheaper, and more convenient for regular tourists. Despite the presence of such rivals, travel agencies have not yet ceased to exist and continue to provide services to tourists.

Whereas smartphone applications are used to satisfy users’ spontaneous needs (e.g., collect information about a landscape or check the list of festivals available during the user’s vacation), online websites and travel agencies provide either tickets or tours to end-users.

As such, they are less focused on providing context-aware recommendations (as applications do) and pay more attention to either specific parts of the journey (tickets) or full-scale traveling services (tours). All of these agents (apps, websites, and agencies) target customer satisfaction; satisfaction can be described as the customer’s evaluation of the received services/products in terms of their alignment with customer’s expectations (Kobylanski, 2012). The purpose of the project is to address the following questions:

- How did the Internet affect the travel industry about customer satisfaction and service convenience?

- Are travel agencies able to compete with online apps/websites that offer similar services?

- How can travel agencies compete with online websites that sell tickets in British Columbia, Canada?

The project is important because the majority of studies address the influence of the internet on the travel industry either on a global (worldwide) level or a local (within a city/country) level. Previous research did not target British Columbia as the primary aim, and the issues experienced by travel agencies about the Canadian context remain underresearched.

Literature Review

The literature review aims to examine how the problem of travel agencies and online websites/applications and their impact on the traveling industry are addressed in current research. A little research is dedicated to British Columbia, the author will review studies dedicated to the problem of competition between online services and tourist agencies in different countries and apply the theory to the research questions of the current study.

Kobylanski (2012) points out that travel agencies gain significant support from the base of long-term customers who are loyal to a company and are satisfied with their services. The author points out that the popularity of travel agencies over online services is explained by the following factors: since vacation time cannot be restored, customers are interested in less risky, more reliable, and well-tried agents rather than a random internet website (Kobylanski, 2012). Customers are also aware that travel agencies can provide a variety of services (travel packages, different/rare destinations, etc.), whereas ticket-selling websites and apps are incapable of doing so.

Smartphone applications, at the same time, work at a different level and target other consumers’ needs. Smartphone-enabled services are more supported by customers who prefer real-time smartphone-based services such as live trip route recording or random choice of a nearby restaurant, for example (Wang & Xiang, 2012). Such services are not provided by travel agencies and are parts of the “augmented reality” created by smartphone apps to transform tourism experiences.

While travel agencies provide an established set of packages with different services, applications focus on “information search, reservation, and e-commerce, [and] multimedia content consumption” (Wang & Xiang, 2012, p. 11). The role of social media in tourism is somewhat different; online reviews tend to increase tourists’ confidence in decision making, reduce the perception of risk related to the website, and facilitate their choice of accommodation (Fotis, Buhalis, & Rossides, 2012).

The empowerment of tourists by travel applications and user-generated content is also examined in the work of Filho and Machado (2011), who argue that consumers feel empowered when they have access to information and can take voluntary action, thus developing their potential via informational services (apps and websites). Together with psychological empowerment theory, the authors also use dual-process theory to explain which informational factors influence consumers’ decision-making about the validity of online review platforms.

The dual-process theory relies on two types of influence on the persuasiveness of a message: informational social influence (ISI) and normative social influence (NSI) (Filho & Machado, 2011). When using ISI, consumers evaluate argument quality, information framing, and source credibility; NSI emphasizes consistency and recommendation rating. Thus, with the help of user-generated content (reviews of apps and online websites), consumers can plan their vacation or trip without the assistance of another agent (travel agency), which increases their bargaining power.

Law et al. (2015) examine the role of traditional travel agencies, e-commerce, and the Internet in the travel industry. They provide different points of view on the future of traditional travel agencies: on the one hand, the availability of information online and easy access to it eliminates the need of consumers to be physically present in travel agencies when choosing the preferred destination (Law et al., 2015). Furthermore, the emergence of online search engines provides consumers with a broader and richer set of opportunities than offline agencies do. The bargaining power of suppliers (hotels and resorts) also grows, as they prefer offering services via their websites or booking apps (sometimes at much lower prices than traditional travel agencies).

On the other hand, traditional travel agencies rely on direct (physical) human interaction that online services are often unable to provide. Traditional agencies are popular among some groups of customers, such as business travelers, organized (group) travelers, senior citizens, customers with low educational levels, and customers who buy complex traveling packages. Not all online websites (if any) can offer travel mixes (common among travel agencies) that will align with every need of the customer.

Additionally, some consumers express doubts about data security when they consider booking a hotel online and prefer to consult traditional travel agencies instead (Law et al., 2015). It should also be noted that not all travel agencies view the Internet as a threat since some of them use it as an opportunity to present their services via the company’s website, Facebook or Instagram account, etc.

The impact of travel search engines and resulting commission cuts on travel agencies is discussed by Khuja and Bohari (2012). Airlines prefer selling tickets directly to consumers as web fares are much lower and there is no need for booking fees and commissions. Additionally, airlines are not interested in intermediate agents because travel agencies can provide consumers with objective information (advantages and disadvantages) of each airline, which can alter consumers’ intentions.

To increase competitive advantage in a highly competitive environment, travel agencies use customer-oriented services, niche marketing charging fees, added value, alliances, and the adoption of the Internet as survival strategies (Khuja & Bohari, 2012). The elimination of airline commissions resulted in adverse outcomes, as many agencies had to leave the business; those that remained had to charge higher service fees, which made their services unavailable for customers with low income.

Although travel agencies recognize the importance of the Internet in online booking and research of destinations, they rarely use it to increase their competitive advantage and improve relationships/communication with current, loyal, or potential clients (Khuja & Bohari, 2012). Thus, it appears that travel agencies are yet unable to fully exploit the Internet in their favor.

Additional attention should be paid to Airbnb and services similar to it (e.g., Couchsurfing). Airbnb is described as a disruptive product that was able to transform the market. According to the disruptive innovation theory, such disruptive product might underperform when compared to prevailing products (services, in this case) but offers “a distinct set of benefits, typically focused around being cheaper, more convenient, or simpler” (Guttentag, 2015, p. 1202).

Although the disruptive product may not be beneficial at first, with time it improves and attracts a higher number of customers from the mainstream market. Big players in the industry who were focused on more profitable markets at first eventually pay attention to the disruptive product, but by that time it can gain such support that leading players are unable to compete anymore. Guttentag (2015) notices that such a process occurred in the travel industry as well when the emergence of Airbnb together with online traveling agencies (Expedia, Orbitz, etc.) had decreased the competitive advantage of traditional travel agencies by offering cheaper and convenient although less personalized services.

One of the major advantages of Airbnb compared to traditional agencies is the tourist’s ability to have authentic, colored with local specifics travel experiences as tourists stay not in hotel rooms but real flats/houses of residents. Just as travel agencies ensure the safety and reliance of hotels they cooperate with, Airbnb provides complex identity verification procedures for hosts to ensure customers’ safety. With the constant improvement in quality, Airbnb becomes a severe rival both for online and traditional traveling agencies.

Rajala and Gao (2013) discuss the influence of product, price, place, and promotion on consumer’s choice of either online or traditional travel agencies. According to the authors, online travel agencies were more supported by the majority of study participants (53%) because they offered a wider range of products of services, whereas 19% of participants stated that online agencies did not provide services attractive to them (Rajala & Gao, 2013). Prices and transactions were also described as advantages of online agencies, as cheaper services and more convenient payment methods made online agencies more attractive than traditional ones.

Place and convenience were the number one reason for choosing online agencies, as accessibility was viewed by participants as the most important factor when choosing a travel mediator. The authors suggested that those who preferred traditional agencies in this case either had no access to the internet or found it challenging to work with online search engines and agencies, thus preferring traditional agencies and the physical presence of the marketing agent (Rajala & Gao, 2013). The promotion was the least influential factor, where both groups admitted they did not find it as necessary as previous factors.

As can be seen, accessibility, convenience, and a wide range of offered services and destinations are viewed as advantages of online travel agencies, search engines, and applications. The preference for traditional agencies remains strong among a specific group of customers or those who have restricted access to the Internet. It is possible to assume that the findings of the literature research will align with the consumers’ preferences in British Columbia and confirm whether travel agencies in this location struggle with the same issues.

Project Methodology/Approach

The literature, focused on the research of the relationships between the internet and online/traditional travel agencies, provides profound insights into the problem, indicating that both forms of travel agencies can survive as they depend on different groups of customers. Thus, the Internet has led to an increase in competitive advantage between online and traditional agencies, but the latter can rely on specific groups of customers to remain in the market and ensure their competitive advantage is not undermined by the emergence of ticket-selling websites and apps for travelers.

At the same time, no extensive research that targets Canadian provides in general or British Columbia, in particular, was found. The author aims to address this gap and evaluate the competitive advantage of travel agencies by examining those located in British Columbia. The section aims to introduce the study design and a detailed description of the research strategy, including the process of data collection, to the reader.

Study Design

The study will be a descriptive non-experimental qualitative survey research; the author aims to use pre-structured (deductive) surveys as a tool for data collection. Pre-structured surveys define main topics, dimensions, and questions before the surveys, and the author uses a structured protocol (e.g., a questionnaire/survey) for data collection. To answer the research question, the author aims to conduct five to ten surveys of traditional travel agencies located in British Columbia, Canada.

Unlike quantitative studies, qualitative studies usually use smaller sample sizes to gain more detailed, although less generalizable data (Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014). The grounded theory will be used for the qualitative analysis of survey answers; the systematic methodology of the grounded theory allows building a theory based on data, hypotheses, opinions, suggestions, and considerations collected during the research from study participants.

Participant Selection/Sample

The study will target the local population, i.e., Canadian travel agents and managers who reside and work in British Columbia. Minimum variation sampling will be used to address a specific sample size and a narrow set of theories and considerations (the impact of the internet on traditional agencies, the competitive advantage of traditional agencies in British Columbia, etc.). Purposive sampling will focus on Canadian travel agents who have been working in a traditional travel agency for at least three years. The sample size will include approximately five to ten travel agents. Inclusion criteria will be the following:

- Travel agency/agent works in British Columbia.

- Is engaged in the industry for more than three years.

- Aware of the presence of online search engines for tickets/hostels and has used them in their practice.

- Does not aim to change occupation and/or place of residence in the next year.

Unit of Analysis Selection

The units of analysis will be recurrent themes or statements in participants’ answers to surveys (e.g., “the internet significantly changed tourism”, “travel agencies cannot compete with online apps”, “online apps help attract customers”). As the research aims to understand whether traditional travel agencies can find tools/ways to compete with online websites, units of analysis will include descriptions of methods of how this competitiveness can be increased (e.g., by marketing, unique travel packages, quality customer service, etc.).

The rationale for the Number of Participants/Units Selected

The small number of participants and units of analysis is necessary for this study as it focuses on the examination of specific issues in a defined location; large sample sizes are needed to provide generalized results, whereas this study aims to understand the competitive process in a given Canadian province. The small number of units will represent tools and strategies used by traditional travel agencies to compete with online agencies; the majority of these tools is described in previous research and limited to a specific set of interventions (e.g., “online advertising”, “packages for loyal customers”, “complex three-in-one services”, or other).

Added Value of Research

The research will provide information for different stakeholders (customers, agencies, agents) about the impact of the Internet on traditional and online agencies and emphasize what strategies traditional travel agencies need to use to compete with the increased number of rivals in the market.

Travel agents can assess the effectiveness of their competitive strategy and consider using new tools to attract customers, for example, by comparing the reliability and quality of services provided by online websites to the services at their agency. Customers can evaluate the quality of both types of agencies in British Columbia and decide which one of those is more suitable for their preferences and needs. Agencies as organizations will be able to understand the dynamics of the tourism market and industry and change or review their business processes accordingly.

The emergence of sustainable tourism in British Columbia can also indicate in what directions traditional travel agencies should look. The rising support for eco-tourism and concerns with environmental issues, such as wildfires, become significant factors that transform the travel industry (Lindsay, 2017). To survive and stay competitive, traditional travel agencies can consider sustainable tourism as an addition to their tour packages that will attract new customers and provide them with an advantage that websites and applications are unable to offer. The competitive strategies of travel agencies might rely on online tools, thus adding value to them, but an entirely new view of tourism and traveling can change the role of traditional agencies, transforming the business in a way Airbnb or any other innovation did.

Online applications and websites that sell tickets/hotel reservations are rarely able to offer more complex packages or tours, whereas consumers keep seeking unique traveling experiences that sometimes neither online nor offline travel agencies can offer.

The findings of this study will indicate whether travel agencies in British Columbia are stagnating or successfully adapting to new trends in and demands of the market. Depending on the study’s results, stakeholders (agents and agencies) will have the opportunity to compare their strategies to those presented in the research and evaluate whether their implemented plans are effective. The study might offer new considerations to stakeholders.

Research Instrument

The research instrument will consist of eight open-ended questions that will target the recent changes in the tourist industry and address agents’ perceptions of strategies or tools used in the industry that are either online or offline-based. Five of the questions are borrowed and adapted from the study conducted by Law et al. (2015, p. 436). To view the questionnaire, see Appendix.

The questionnaire can be divided into three themes: sources and channels of business, the impact of the Internet on business, and other strategies used to attract customers and stay competitive. The first question is related to the first theme, the second to seventh questions are related to the second theme, and the last question is related to the third theme. The question about other strategies used for competitive advantage was placed at the end of the questionnaire to bring participants’ attention to offline tools that increase competitiveness.

Data Collection

The author will collect data using notes and audio recordings to ensure that all recorded and collected information is stored and will be available to further analysis and evaluation. The author aims to ask participants to review the notes taken during surveys to ensure that their answers are scripted and understood correctly. Additionally, all participants will be asked to provide informed written consent.

The data will be collected during the interviews. As Taylor, Bogdan, and DeVault (2015) point out, the researcher can ask participants to elaborate on a subject or opinion expressed during the survey to round out the researchers’ knowledge about a specific issue. Therefore, it is important to address answers as quickly as possible to formulate more detailed hypotheses.

The data collection will take place on-site, during the conduction of surveys. All participants will be encouraged to add new information to their previous answers if possible before the end of the survey. The sequence of events is as follows: the author will schedule meetings with participants to conduct the survey; each survey will take up to one hour to conduct; the surveys will be carried out during one to two weeks; the author aims to conduct one survey per day in case if any of the meetings will be postponed for several hours.

All collected data will be analyzed with the help of qualitative programs such as MAXQDA or Transana that allow transcribing text from audio recordings, grouping recurrent themes, and coding important topics or frequent statements (MAXQDA, 2017). The most frequent comments, descriptions, tools, strategies, etc. will be divided into several groups (e.g. “offline tools”, “online tools”, “adopted strategies”, “effective strategies that are rarely used”, and others). This analysis will help the author understand how the internet influenced the travel industry and how traditional travel agencies can remain competitive.

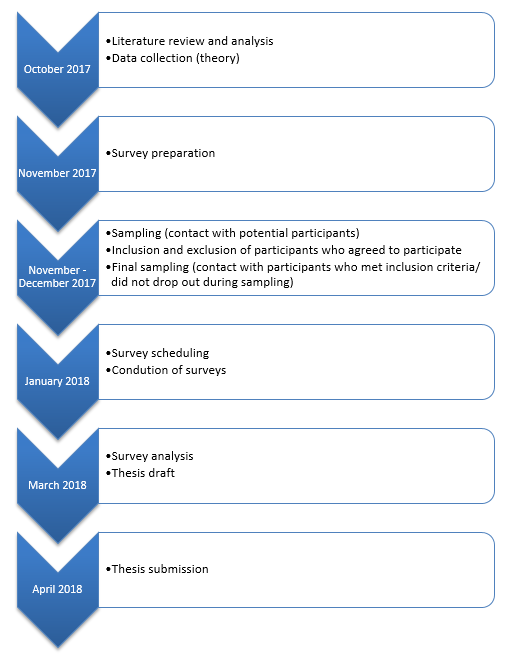

Timeline

References

Filho, M., &Machado, L. A. (2011). Understanding how user-generated content empowers the online consumer in the travel industry. Web.

Fotis, J., Buhalis, D., & Rossides, N. (2012). Social media use and impact during the holiday travel planning process. In M. Fuchs, F. Ricci, & L. Cantoni (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2012 (pp. 13-24). Vienna, Austria: Springer-Verlag.

Guttentag, D. (2015). Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(12), 1192-1217.

Khuja, M. S., & Bohari, A. M. (2012). A preliminary study of internet based ticketing system impacts on selected travel agencies in Malaysia. Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 2(10), 219-230.

Kobylanski, A. (2012). Attributes and consequences of customer satisfaction in tourism industry: The case of Polish travel agencies. Journal of Service Science (Online), 5(1), 29-42.

Law, R., Leung, R., Lo, A., Leung, D., Hoc, L., & Fong, L. H. N. (2015). Distribution channel in hospitality and tourism: Revisiting disintermediation from the perspectives of hotels and travel agencies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(3), 431-452.

Lindsay, B. (2017). ‘It’s been a challenge’: B.C. tourism operators feel the heat from wildfires. Web.

MAXQDA. (2017). What does MAXQDA do? Web.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A method sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications.

Rajala, T., & Gao, X. (2013). Online vs. traditional travel agency: What influence travel consumers choices? Web.

Taylor, S. J., Bogdan, R., & DeVault, M. (2015). Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Wang, D., & Xiang, Z. (2012). The new landscape of travel: A comprehensive analysis of smartphone apps. Web.

Appendix

- What are the major sources (such as geographic markets and trip purpose) and channels (such as online or offline channels and booking sources) of your business?

- Have the Internet, online apps, and/or airline ticker online search engines changed your business mix? If yes, how?

- Have you implemented significant changes in the business process to adapt to the prevalence of the Internet and mobile applications?

- Does the management of your company invest in Internet and mobile technologies to increase competitiveness?

- Do you think that the role of travel agencies has changed with the emergence of online travel agencies and websites similar to booking.com, Airbnb, etc.?

- Have you experienced difficulties in attracting new customers due to websites that provide online reservations and search engines for airline tickets?

- Do you have Facebook/Instagram/Twitter accounts? Are they helpful in attracting new customers? How?

- What other, non-Internet based tools do you use to stay competitive in the changing tourism market?