Introduction

Political human thought has always been a dynamic reflection of the general mood of an era, and therefore it cannot be said, for example, that the period of ancient Mesopotamia and the time of the French Revolution were characterized by uniform views of the political organization of society. In other words, each historical period is characterized by the emergence and spread of its socio-political currents that put specific aspects of human or social life in the foreground. One such form is liberalism, the flowering of which is traditionally equated with modern history, although liberal philosophical principles were also reflected in ancient states. This historical essay seeks to trace the development of liberalism in the European regions of the nineteenth century and to identify the attitudes toward this political current of iconic figures of the time.

History of the Development of Liberalism

The foundation of liberal views is the understanding of the absolute inviolability of fundamental human rights. Among such inalienable, natural rights of every citizen of the world are the right to life, the right to political freedom, and the will to govern one’s own life. It is important to emphasize that such rights are realized only when they do not interfere with the realization of the rights of another person. For example, an individual cannot claim freedom of movement in a city if he wishes to enter the private property of another individual. It is noteworthy that fundamental liberal rights began to appear in ancient civilizations. Thus, the cuneiform writing of Cyrus the Great of ancient Babylon reflects the basic rules and laws of modern society in communities four thousand years old (Zournatzi 150). However, Cyrus the Great and liberal leaders like him were only rare examples of monarchs recognizing the rights and freedoms of their subordinates. It was not until less than two centuries ago that liberalism as a political and social movement was really fully recognized.

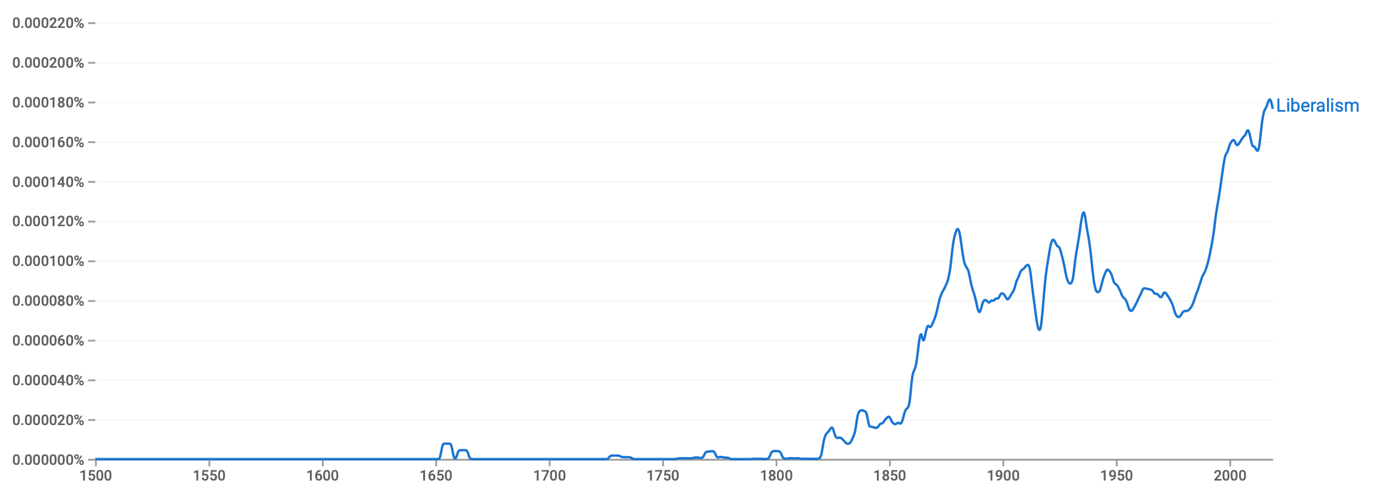

Although liberal ideas have always been valid, true liberalism only became relevant to public thought in the nineteenth century. Figure 1 illustrates this trend perfectly: mentions of the word “liberalism” in printed books intensified from the second quarter of the century before last and peaked by the end of that period. In other words, liberalism only became particularly popular in the nineteenth century, whereas at other times, it existed but did not generate as much public resonance.

The actual beginning of the politics of liberalism was the Enlightenment when the European thinkers and monarchs they influenced explored radically new thoughts. Instead of traditional serfdom and slavery, philosophers began to propose alternatives in which human freedom was of paramount value, and thus the state system had to be qualitatively changed. European liberals postulated revolutionary reforms, among them the abolition of the feudal system, the restriction of the role of the church in state activities, the abolition of absolutism, and the granting of equal freedoms to all citizens of a single country. Thus, the emergence and strengthening of the public role of philosophers were one of the determinants of the realization of liberal practice.

In fact, it is possible to study history even more deeply in order to understand that the flowering of liberalism in nineteenth-century Europe is a consequence of the change in intellectual intelligence in medieval European regions. As it is known, the Middle Ages were characterized by a predominance of mythological thinking, with the church as the main lever for all decisions. Scientists, independent women, and other undesirable members of church society were burned at the stake and tortured in public only because they did not fit the image of the average citizen of a European country of that era. As time went on, however, increased individuals realized that such a social order was hardly conducive to success. Moreover, science could not be built on the basis of cooperation with the church alone. In other words, there was an apparent Marxist class conflict in society, which led to a reversal of polarities. Thus, the European religious world became an environment of rational thinkers who preferred empiricism.

There is another medieval factor that led to the flowering of liberalism in nineteenth-century Europe. In particular, at the end of the Middle Ages, there was a transformation of consciousness in which people ceased to be classified according to state estates. The economic development of states led to the general decision that slavery was no longer as profitable an economic force as industrialization. From this follows the need to find new concepts of profitability of production catalyzed the assignment to enslaved people of the status of free members of society who could toil in production.

The social revolutions and declarations signed earlier were not insignificant driving forces behind the flowering of liberalism in Europe. For example, the experience of the American Civil War of Independence showed the world the validity of the concept of inalienable rights. It was then, in 1789, that the American Bill of Rights was adopted, which guaranteed the basic principles of the liberal agenda in the United States (“The Bill of Rights”). The European states wanted to keep up with the emerging world trends, and that is why the French Revolution took place in 1789, which made France officially a liberal country. Thus, by the end of the eighteenth century, on the basis of the revolutions, the ground was prepared for the realization of the basic principles of liberalism.

The Attitudes of the Significant Others

Given the widespread dissemination of liberal ideas in nineteenth-century Europe, it is reasonable to assume that the most prominent political and social figures supported these views. One of the foremost figures of liberalism is John Locke, who, as early as 1690, considered the inalienable rights of the individual and recognized the people as the sources of total state power (Hendricks). Development of these ideas was found in John Stuart Mill, who showed the active role of the state in protecting the freedoms of the citizen (“The Literature of Liberalism”). Radical views of liberalism are found in Thomas Paine, who rigidly drew the line between the state machine and the individual liberties of the individual. It was Paine’s efforts that are believed to have made possible the high-profile revolutions in the United States and France. Adam Smith viewed liberalism in terms of economic forces, arguing that the freedom to choose labor engenders natural competition (Hendricks). Thus, liberalism was a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that could be looked at from many different angles.

Conclusion

To summarize, liberalism is the next milestone in the development of the social and political thought of humanity. Recognizing the impossibility of slave use of human beings, thinkers and rulers have long thought about adopting the ideas of justice and equality as forms of liberalism. The concept of inalienable rights and freedoms is the apogee of the development of liberal philosophy, in which each person is viewed as a bearer of equal rights. This essay has shown that the development of liberalism, although its ideas were not new, occurred in nineteenth-century Europe. The critical factors of this flowering have been discussed at length in the paper. In addition, it has also been shown that liberalism is not a straightforward and unified concept, which means that many thinkers and authors use its philosophy in different ways to create their doctrines.

Works Cited

“The Bill of Rights: What Does it Say.” America’s Founding Documents, 2020, Web.

Hendricks, Scotty. “Classical Liberalism and Three of Its Founders: Explained.” Big Think, Web.

“The Literature of Liberalism.” The Economist, 2018, Web.

Zournatzi, Antigoni. “Cyrus the Great as a “King of the City of Anshan”.” Tekmeria, vol. 14, 2018, pp. 149-180.