Introduction

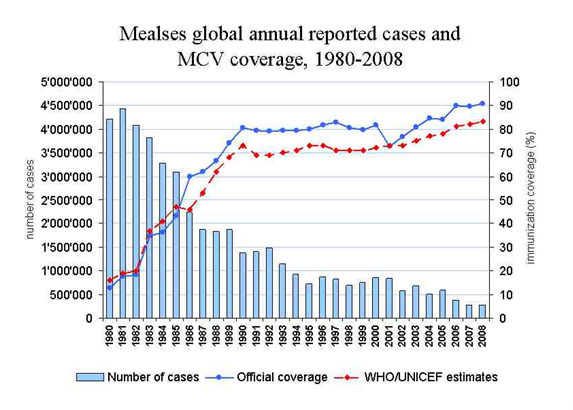

Historically, there was a very high infection of measles among children (95%-98%) by the time they reached 18 years, before the introduction of the vaccine against measles. The number of cases of measles has generally reduced since 1980 according to the WHO report (Figure 1). The viruses for measles have an incubation period of 8-12 days after which the patient experiences increasing fever (to 39-40.5 degrees centigrade).

Other symptoms that the patient experiences are conjunctivitis and coryza. The patient may experience intense symptoms two to four days before the appearance of a rash and the symptoms may reach optimum on the first day of the appearance. Measles, which was responsible for 1.1 million deaths in 1990 and 1 million in 1996, was ranked as eighth amongst 107 causes of death by the Global Burden of Disease Study. A vaccination strategy that had been developed by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) was to be used to aid in the interruption of indigenous measles transmission by the end of 2000, in the Region of Americas (Rosario, et al., 2003).

Among the deaths of children aged below five years, measles has been the highest killer despite global measles vaccination coverage of about 80% over the past decade. In the year 2000, there were about 31 million measles cases and 777,000 deaths with Africa having the highest number of deaths (452,000), followed by Southeast Asia which experienced 202,000, and the Eastern Mediterranean which experienced 81,000 deaths from measles. Among the deaths caused by vaccine-preventable diseases, measles was responsible for 44% among children aged below 15 years old. Those affected were the poor communities experiencing emergencies, characteristics of low vaccination coverage, overcrowding, and malnutrition.

Despite some countries like South Korea and Sri Lanka having introduced and achieved high vaccination and single-dose strategy, there have been reported large outbreaks in these countries. A strong immunization program established in areas like China also does not seem to have stopped transmission of measles which is facilitated by the high population in these regions. High population densities have also been responsible for high rates of transmission in areas like the Tanzanian refugee camp. Large outbreaks in the African regions could not be helped by limited-scale mass vaccination campaigns and low-to-moderate routine measles vaccination coverage. These vaccinations, for example, targeted a limited age range, for instance, 9 months to 4 years (Rosario, et al., 2003).

Vaccination has proved to be effective in controlling measles as incidences of the disease have reduced in all countries and regions which had attained high coverage with the measles vaccine. Interruption of the transmission of the measles virus has been experienced in many cases, as well as deaths and measles cases reduced, in regions like the Americas and southern Africa where aggressive measles control or elimination strategies have been implemented.

Countries in the areas where there was low uptake of measles vaccine-low coverage with the first dose and/or with no second opportunity for measles immunization, (for example western Pacific, Middle East, some parts of Europe, sub-Saharan Africa) experienced high measles burden. The safety of the measles vaccine has been proved with rare serious adverse events of measles vaccine or combined measles-rubella vaccine during mass vaccination campaigns. Further, during the vaccination of children in masses and adolescents in New Zealand, Romania, Costa Rica, South Korea, Australia, Canada, United Kingdom (UK), no death was associated with measles or measles-rubella vaccine.

Coverage of measles vaccination in the UK, Sweden, and other industrialized countries was interrupted by the allegations that the combined measles-mumps-rubella vaccine may cause autism and/or inflammatory bowel disease among recipients.

The group of school-aged children that have not received vaccination against measles is the most susceptible to the disease and may act to fuel epidemics.

In addition to vaccination, the public health care systems have been using public education to help in the eradicating of measles. Surveillance of the healthcare system has also been applied to help in the eradicating of measles.

Causes of measles

Measles is a disease caused by a group of a virus of the genus morbillivirus, namely, the paramyxovirus. The genus type is negative-sense, single-stranded, and enveloped. According to WHO, measles manifests with the occurrence of fever with maculopapular rash. In addition, the aforementioned is accompanied by either cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis. The highly contagious disease is spread through direct contact with the infected person’s nose and mouth or through aerosol transmission. The rash appears first on the face and neck as lesions-discrete erythematous patches 3-8 mm in diameter. Lesions may also be found on the palms and they may increase in number for 2-3 days.

Measles at a complicated stage has no specific treatment but fluids, antipyretics, and nutritional therapy can be provided as supportive care. Secondary bacteria infections such as pneumonia may be dealt with by antibiotics. Vitamin A has been observed to reduce the mortality rate for measles by 30-50% when administered to patients. Measles disease is common among refugees and displaced persons because it is facilitated by high populations and population movements (Kamugisha, Cairns, Akim, 2003).

Increased risk of death from the disease has been associated with poor nutrition under the conditions of high populations and population movements, for example for the refugees (Toole, Steketee, Waldman, Nieburg, 1998). Refugee camps experience conditions of undernutrition, and the provision of adequate food rations has been ranked as the priority for the prevention of mortality deaths among the populations in the refugee camps, and other similar places.

Spread of measles in the region of the district of Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu India between December 2004 and 2005 as a result of Tsunami. This was despite the one-dose vaccination against the disease in the state. The absence of fatality cases could have been as a result of early case detection and management whereas the decreased population of susceptible children in Tsunami leading to reduced spread for the children between six and sixty months, could have been as a result of supplemental measles immunization.

Viral exposure, immunodeficiency, and malnutrition are host factors that could lead to post measles complications according to Robin et al., (2005). These factors could also lead to increased case-fatality rates (CFR).

Control for Measles

About 197, 000 deaths were reported from measles in 2007 despite rates of success in control. The World Health Organization observed from a review of literature on the impact of immunization control activities in middle and low-income countries from 1977 to 1993 (Aylward, Clements, & Olive, 1997) that effective immunization response was hampered by either a too rapid spread of outbreak or too late detection of most outbreaks (WHO, 1999).

A review of this conception was later carried out in consideration of field data, literature, and unpublished work. The WHO set a target of a 90% reduction in measles mortality by 2010 in comparison to 2000, in their World Health Assembly in 2005. Deaths from measles have been reduced by 74% worldwide since the year 2000 according to the WHO (2009 expanded program). The WHO had measles elimination goals in four of the six regional offices as of 2008 and only two of the six had mortality reduction goals. Health sector reforms and decentralized in countries where they have not been achieved may help by raising accountability and more resources at lower levels of governance, and hence leading to increased immunization levels.

Public health systems have made important steps in the eradication or control of measles, one of this being immunization and vaccination. The provision of the first dose for the measles vaccine has been widely successful through the public health systems. There is however the need to promote the possibility of providing a second dose for the disease. The importance of a second opportunity for immunization can be perceived in the fact that sometimes, response to vaccination does not occur in that the people vaccinated may fail to develop immunity. Others miss vaccination and therefore a second chance would be appropriate.

Population immunity may be more difficult to achieve in countries or regions with limited or poor access to preventive health services for example Zimbabwe, Turkey, and parts of Latin America. This may however be helped out by follow-up and catch-up campaigns. These campaigns may help in tracking the children who were not immunized against the disease, in addition to offering a certain degree of certainty that more people would not miss it.

In Latin America, Africa, and Europe, evidence exists that national wide SIAs which targeted children of all groups with high susceptibility (mostly 9 months through 14 years) were able to reduce measles mortality even to zero and prevent outbreaks. All geographical and age groups with high susceptibility to measles (above 5%) need to be covered and targeted by the SIAs for it to be successful.

Training and supervision of SIAs are important to reduce vaccine wastage rates. Transmission of measles is successfully interrupted with the epidemiologic and virology surveillance as evidenced with countries like Wales and England (Strebel, et al., 2003). To sustain interruption of measles transmission, it is necessary to maintain the level of immunity of 91%-93% (herd immunity threshold for measles in industrialized countries as found through mathematical models estimate) which is consistent with the immunity level of 90% to 95% as found in the seroprevalence studies in the USA and other developed countries (cited in Strebel, et al., 2003).

The importance of careful organization of resources and staff in the healthcare in a country is very important because such as large outbreaks of measles may cause diversion of resources and staff for preventive and clinical service purposes and lead to high financial costs. Measles continues to be imported from countries with fewer population immunities. To evaluate the impact of programs in measles control, measles infection should be evidenced by laboratory confirmation.

Clinical diagnosis of measles becomes unreliable if there is a very low measles incidence, for example as realized after a successful catch-up campaign. Laboratory confirmation may therefore be necessary under such conditions. The ELISA (1gM) on a serum specimen is the most widely used diagnostic essay for measles, but oral fluid specimens are common in England and Wales. A new method that would offer advantages of easier specimen collection and transportation involves ELISA testing of serum from filter paper blood spots but was not in use (Bellin & Helfand, 2003).

An effective monovalent measles vaccine is made from live attenuated virus and has been estimated to have 85% effectiveness when administered at 9 months of age. The vaccine is of freeze-dried form and is reconstituted with measles diluent/solvent from the same manufacturer. Storage of reconstituted measles vaccine in a cool and a place shield from sunlight is important since it loses its efficacy (for example about 50% efficacy in one hour at room temperature (22-25 degrees centigrade)) and inactivation within one hour at 37 degrees centigrade.

Three contraindications to measles that have been identified include pregnancy; the severely immunocompromised for any reason; and cases of previous allergic reactions like shock, hypotension, and difficulty in breathing, swelling of the mouth or throat, and hives-after a previous administration of the vaccine or vaccine component.

There is evidence that communities have accepted large outbreaks of measles in the high burden countries, and the expanded use of second opportunity immunization by mass vaccination campaigns has aided in the reduction of measles incidences. Once there is an outbreak of measles, the responsible authority should emphasize a primary goal of reducing morbidity and mortality child vaccination and case management.

In addition, secondary goals that are to be focused on are to monitor the changing epidemiology for the disease, raise awareness in the community about the disease and its prevention, identification of groups that are faced with high risks to improve coverage of immunization and other control measures, limiting the spread of the disease, and the identification of the weaknesses and shortcomings of the vacci0naition programs and other control measures such as surveillance.

To aid the reduction of the measles problem worldwide, WHO and UNICEF came up with a strategic plan that targeted 47 countries worldwide, which were in two regions with the highest measles burden-majority of global deaths from measles and complications. These areas are Africa and Southeast Asia. All successful groups of children aged 9 months or shortly after, would receive the first dose of the measles vaccine. It would be necessary that assurance that each child received the first dose through the provision of a second immunization opportunity. The strategic plan also envisioned the guaranteeing of a second opportunity for measles vaccination. The latter would be achieved either by routine immunization or campaigns. Children who were immunized by the first dose would also receive a second immunization.

Among the practice that would help in the reduction of the problem presented by the measles disease in the two aforementioned regions include the measles surveillance and monitoring through appropriate systems and integrating of these two with laboratory and epidemiological information (WHO, 2009) within public health care systems and institutions. This practice would however require the combination of efforts by the WHO and the local authorities to mobilize global and local resources to achieve these goals. This means that it is important to prioritize the measles control programs in these countries. The strategic plan would also see that there would be improved clinical management of every measles case.

Immunization has been ranked as the second in importance in the control of death mortalities from measles from the provision of adequate food rations. Recommendations exist for the immunization of any child of 6months to five years as soon as they enter organized camps or settlements and that those identified as undernourished should be prioritized under conditions of inadequate measles vaccines (Toole, et al., 1998). Because limited access to basic care service has been blamed for the existing problem with measles (cited in Robin, Thomas, Maman, Jose, Rene, Robert, Peter & Lisa, 2005), control can be achieved with increased health care facilities.

It is therefore the responsibility of the government to ensure that populations have access to as many care centers as possible. Improved access to hospitals especially in rural areas can lead to a rise in the cases of early detection of measles amongst these populations because they may seek medical intervention once they detect the symptoms. To be able to prioritize public health programs for the control of measles, it is imperative to effectively estimate the burden of measles to populations. The burdens will be determined through the consideration of the measles CFR (Robin, et al., 2005.

Surveillance of the morbidity and mortality for measles within public healthcare systems of various countries is important as a step towards the identification of areas and populations that are at risk. This would lead to the taking of immediate steps before the worst scenarios occur. This surveillance is important because complications arising from measles may be curtailed. Reporting on communicable diseases amongst the populations is available in countries like India, where measles has been identified with complications such as corneal ulceration, blindness, pneumonia, otitis media, and severe diarrhea among others.

The surveillance may involve the monthly reporting of the aggregate number of measles cases and deaths at the local health care facilities and which are submitted to state departments for appropriate actions (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2005). Catch-up or follow-up campaigns helped in the provision of immunization to nearly 500 million children between 2000 and 2006. Education on the dangers, spread, control, morbidity, mortality, and other information on measles can help the control of the disease.

In the control of measles, there have been identified implications that are barriers to control. Various regions have expressed a strong political will towards the elimination of measles, whereas others are still yet to prioritize the measles. Regions of the Americas has had a strong political will to eliminate measles as evidenced by the resolution reached by Western Hemisphere ministers of health to eliminate measles by 2000.

South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa which have high rates of deaths of children as a result of measles have also experienced the high political will to eradicate measles, unlike low political will in some of the industrialized countries such as Germany, Italy, France, and Japan. The political will to eradicate the disease is important because immunization programs require devoting resources that may include local and national resources whose usage may be under the discretion of the politician. In addition, mobilization of the locals and nationals to participate in vaccination programs require governmental support to succeed, and more inevitably, the control of health facilities and staff through the direction of public healthcare facilities.

Partnership and advocacy between the concerned authorities such as ministries of health, private organizations, WHO, and UNICEF are also necessary to mount up substantial control efforts. These efforts have led to the establishment of practices or strengthening of other practices to ensure the provision of a second opportunity for immunization in the public health care systems. Advancement of separate efforts towards eradication of measles may not achieve as much as collaborative efforts would, in case of global control for the disease.

In addition, some collaboration such as that between global organizations such as WHO and local ministries are inevitable for the success of vaccination and other control programs in some countries. A collaboration of CDC, WHO, UNICEF, and the UN Foundation, termed as the Measles Initiative was formed in 2001, and supported an initiative that saw more than 60 million children vaccinated and thousands prevented from measles deaths in 14 African countries through mass vaccinations.

The importance of the adequate provision of measles vaccine within the public health care system, and the accessibility of it are important. In this respect, there have been efforts to increase the number of public health facilities available for immunization. Reduction of the capacity of measles vaccine below the levels realized in the 1990s to the position where the supply closely approximated the anticipated demand, has led to risks of shortage of the vaccine if there is an unexpected production problem. There is also the need for advanced studies, research, and development into the complications, realities, and developments of measles.

There are some of the issues identified by the Steering Committee for Measles Research which met in 2000, that required research and development. These issues included the development of a new vaccine that could induce immunity in the presence of maternal antibodies, the delivery method for the vaccine which is easier and cheaper, the ability of PAHO strategies to stop the transmission of the disease in Asian and African megacities, and the interaction between HIV and measles (Strebel, et al., 2003).

Public health care systems have also engaged in raising awareness about the illness among the populations. There are required strategic measures to ensure that there is education about the facts on measles about the means of transmission, exposure, control, and the dangers associated with the disease such as complications.

Mortality, Epidemiology, and Morbidity

Measles has been blamed as a cause for child mortality in developing countries. In 2000, it caused the death of 770,000 around the globe, and this represented about half of the deaths that could be prevented by vaccines. High measles infant morbidity and mortality in the developing world have been blamed on the lack of delivery of at least one dose of measles vaccine. Vaccination cannot be viewed as an awesome solution to the spread of measles since the outbreak of this disease has been experienced in the past in the regions of South Korea, Latin America, Romania, and Sari Lanka despite high coverage with single-dose vaccination.

However, vaccination has remained low in African and Southeast Asian regions with a reported 65-67% IN 2003. WHO recommended that high routine vaccination of above 90% in each district and provision of a possibility of a second opportunity for measles vaccination of every child would help in the reduction of mortality and regional elimination. These recommendations were posited in their 2001-2005 WHO/UNICEF strategic plan. The former WHO position that the course of measles outbreak may have not been interrupted by supplementary immunization activities aimed at disrupting virus transmission after an outbreak was challenged by later literature review of 1995-2006 publications (WHO, 2009).

The review of literature has evidenced that an outbreak of measles could last for months within a limited geographical area and that areas of little population movement could slow the geographical spread of the disease. This points out the fact that there would be sufficient time to carry out an immunization response in the area. Outbreak response immunization that was started early, which had high coverage and of a wide age range could aid in the reduction of mortality and the spread of measles. In essence, it was important to consider case fatality rates, population movements, and density, the age distribution of cases, among other issues, while planning to mount up a vaccination response.

Owing to the evidence that immunization response may have an impact on the spread of the virus and the course of the illness, it is important to consider an aggressive and fast response once an outbreak is reported. An outbreak is defined as the occurrence of five or more suspected cases in a 100, 000 population living in a geographical area, in one month. The ability of the health service and its infrastructure is one of the factors that can determine the type of outbreak response.

Other factors that are to be considered include the risk for spread and complications and the level of susceptibility in the population. The WHO recommends the existence of an Outbreak Coordinating Committee where the government and potential partners are represented. This committee is taxed with among other things, making sure there is effective public awareness and involvement, implementing control and preventive measures, ensuring clinical management of cases, and surveillance and notification of suspected cases. The outbreak would be confirmed through a laboratory test.

A method that can be used to trace the geographical origin of importation and to document the elimination of indigenous virus strains is molecular epidemiology.

Conclusion

Measles is a killer disease among infants, causing almost half of deaths resulting from vaccine-preventable diseases. High rates of infection of measles up to 98 % were experienced among children before the age of 18 when the vaccine for the disease had not yet been discovered.

Reduction of these deaths has been realized with the introduction of the measles vaccine and the health care system is doing a lot to eradicate it. To some extent, the public health care system has managed to control the disease as there has resulted in a reduction of cases. Public health care systems have ensured good reporting over incidences and cases, which has helped in eradicating measles.

However, there is much more to be done. About 197, 000 deaths were reported from measles in 2007 despite rates of success in control. Various regions have not achieved similar levels of immunization and therefore the disease burden is not similarly felt throughout. In the year 2000, there were about 31 million measles cases and 777,000 deaths with Africa having the highest number of deaths (452,000), followed by Southeast Asia which experienced 202,000, and the Eastern Mediterranean which experienced 81,000 deaths from measles. Regions of the Americas has had a strong political will to eliminate measles as evidenced by the resolution reached by Western Hemisphere ministers of health to eliminate measles by 2000. South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have also had a high political will to eliminate measles.

Measles is a respiratory illness that is can be controlled through vaccination. It has been recommended that successful cohorts of children who would be susceptible to the attack should be immunized with a first dose, and then an opportunity for a second vaccination can be availed to make sure that those who missed the first one get to be immunized. In addition, because some do not develop immunity against the disease after being immunized, the second chance will offer them protection against measles disease. Immunization programs that are scheduled can prove beneficial, but additional programs are helpful in areas where there are low chances of following up.

The exposure to measles varies among populations, with the attack pitting highly populated and highly mobile populations. Camps are identical to these populations and in addition, poor nutrition makes them more exposed to death. Provision of food has been ranked as the first preventive practice to reduce mortality rates from death from measles. The second one is immunization. Refugee camps and other populations that are in movement and experiencing immediate programs requiring mobility require to be taken care of as soon as possible through aggressive measures of controlling the disease.

The answer towards control of measles seems to go beyond mere carrying out of immunization since it has been indicated that outbreaks occur in areas with immunization practice. There has to have effective immunization strategies established to ensure wider coverage of geographical areas, a wider age range, and to ensure that the second opportunity for vaccination is provided for. Collaboration between the local authorities like the ministries of health of countries concerned and the world body organization involved, such as the WHO would ensure that the immunization programs are more effective. The governments are responsible for channeling resources and human labor to the immunization project.

In addition, the health care system must provide for effective surveillance and monitoring and follow-up program for the measles disease through reporting from the local regions. There was evidence that the previous preposition by the WHO that mounting supplementary immunization could not lead to interruption of the measles virus transmission after an outbreak could not hold water. However, despite the success rate for immunization, there were still realized outbreaks in the specified areas in this study. In areas where the health care facilities are not easily accessible, increasing access may aid the fighting of the illness because it may ensure that more cases are detected as early.

In addition, an adequate supply of the measles vaccine is needed. There is a need to conduct advanced research as pertains connection between measles and HIV, better vaccine delivery techniques, and the ability of PAHO strategies to stop the transmission of the disease in Asian and African megacities. In essence, it is important to consider case fatality rates, population movements, and density, the age distribution of cases, among other issues, while planning to mount up a vaccination response.

Works Cited

Aylward, B., Clements, J., Olivé, M. The impact of immunization control activities on measles outbreaks in middle and low income countries. International Journal of Epidemiology, 26(3):662-669, 1997. Web.

Bellini, J., and Helfand, F. The challenges and strategies for laboratory diagnosis of measles in an international setting. Journal of Infectious Disease; 187(Suppl 1):S283–90.

Case-Fatality Rate during a Measles Outbreak in Eastern Niger in 2003. Web.

Kamugisha, C., Cairns, L., Akim, C. (2003). An Outbreak of Measles in Tanzanian Refugee Camps. Journal of Infectious Disease, 187(Suppl):S58-S62.

McFarland, W, Mansoor , D., and Yang, B. Accelerated measles control in the western pacific region. Journal of Infectious Disease, 187(Suppl): S246-S51.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India. Measles mortality reduction. 2005. Web.

Pistol, A., Hennessey, K., Pitigoi, D., Ion-Nedelcu, N., Lupulescu, E., Walls, L., Bellini W., Strebel, P. (2003) Progress toward measles elimination in Romania after a mass vaccination campaign and implementation of enhanced measles surveillance. Journal of Infectious Disease, 187(Suppl 1):S217-22.

Rosario, Q., Oswaldo, B., Linda, V., Percy, H., Fernando, G., Eric, M., Mauricio, L., Arturo, Q., and He´ctor, I., Interruption of Measles Transmission in Bolivia • JID:187 (Suppl 1). 2003. Web.

Robin, N., Thomas, H., Maman, Z., Jose´, B., Rene, C., Robert, P., Peter, S., and Lisa, C. Case-Fatality Rate during a Measles Outbreak in Eastern Niger in 2003. Clinical Infectious Diseases. , 42, 322-8. 2006. Web.

Robert, P., and Neal, H., The clinical significance of measles: A review. The Journal of Infectious Disease, 189 (Suppl 1); s4-16, 2004. Web.

Strebel, P., Stephen, C., Mark, G., Julian, B., Bradley, H., Jean-Marie O., Edward, H., Peter W., and Samuel, K., The Unfinished Measles Immunization Agenda. The Journal of Infectious Disease. 187 (Suppl 1),1-7. 2003. Web.

Toole MJ, Steketee RW, Waldman RJ, Nieburg P: Measles prevention and control in emergency settings. Bull World Health Organ 1989, 67:381-8.

WHO. Response to measles outbreaks in measles mortality reduction settings: Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. 2009. Web.

WHO/UNICEF joint statement on global plan for reducing measles mortality 2006-2010. Geneva, World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund, 2006. Web.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for epidemic preparedness and response to measles outbreaks: Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response. 1999. Web.