Introduction

Researchers have concentrated on incidental vocabulary learning, especially when examining the efficacy of glosses. From the backdrop of most empirical research studies, Rott and Williams (2003) have established that incidental vocabulary learning can be swiftly enhanced when glosses are made available. This conclusive finding works best when both non-gloss conditions and gloss conditions are compared and contrasted. As a result, it is no longer a matter of inquiring whether incidental vocabulary learning demands the input of glosses. As it stands now, the effectiveness of these glosses is what stands out in most bilingual studies. It is crucial to mention that text glosses have different formats. For instance, numerous comparisons have already been carried out in regards to the impacts of multiple-choice glosses and single glosses. In the case of glosses that are not singular in nature, there are different options in L2. Such procedures can indeed assist in ascertaining how effective certain texts have been altered or modified. Some studies do not show any distinctions between the two categories of gloss. In a research study by Rott and Williams (2003), it was found out that translation was exceptionally effective.

As part of the lexicon studies, lexical items with a trace of ordinary meaning belong to the same conceptual field and form the so-called lexical-semantic fields. The structure a lexical language can be viewed differently depending on the study field. Besides, it may contribute towards understanding the relationship between language and formation of concepts when applied in these fields. In the context of learning a second language and foreign language, Mondria (2003) points to the organization of lexical items in lexical-semantic fields as an effective way of enhancing memorization. Other studies have also showed advantages in the use of these fields in classroom, as when compared to traditional techniques. This study will investigate the impact of L1 and L2 glosses on the acquisition and retention of new words while perusing texts through examination of available literature and proactive test.

Literature Review

L1 versus L2

Mixed results or outcomes have been generated by the attempt to relate the efficacy of L1 and L2 glosses through different methodological tests. For instance, Gardener (2007) has concluded that the two classifications of glosses do not have any difference at all. Ever since the appearance of cognitive sciences and in particular with the emergence of Cognitive Linguistics as new scientific paradigm, it became possible not only to identify in more detail the mental processes relating the learning of any L2, but also to implement effective learning strategies within the functioning of our cognitive systems (Grabe & Stoller, 2004). The concept of mental lexicon, functioning within advances in neurobiological sciences of cognition, has proven to be relevant in teaching and learning foreign languages (Grabe & Stoller, 2004). However, this enthusiasm for the mental lexicon does not mean that there are no controversies in its definition and characterization, as well as to their status and proposed models (Hulstijn, 2001).

In regards to lexical-semantic field, it is pertinent to assert that it is a set of lexical units representing a set of concepts. This may be included in a name tag that defines a particular field. As part of the lexicon studies, we say that the lexical items with a trace of ordinary meaning and related to color or sports activities usually belong to the same conceptual field and form known as lexical-semantic fields. The structure of a lexical language can be viewed partially from each study fields that can contribute even to understanding the relation between language and formation of concepts.

Impacts of Multimedia Glosses

Gloss formats have remarkably changed owing to the introduction and massive use of electronic media such as computers. This implies that verbal forms are no longer the only option when using glosses. Sounds, videos and pictures are some of the multimedia formats that have gradually replaced texts. Therefore, the impacts of multi-mode gloss are now another area of research interest among scholars. This implies that the effectiveness of gloss formats is now being studied from a broad perspective contrary to how it used to be some years back.

During the early 1990s, the Dual Code theory was suggested by researchers with the aim of establishing a firm theoretical base that could indeed be used to incorporate multi-gloss mode (Yoshii, 2006). Memory and cognition are crucial parameters in this theory. According to this theoretical proposition, two unique symbolic systems play a very important role in the acquisition and learning of vocabulary. The first system separately specializes in representing, processing and validating data regarding nonverbal entities and incidences. The other system plays the role of dealing with or managing the key principles of language.

From the theory, it is also assumed that the systems have the ability of working in an independent manner without necessarily relying on each other or external entities. Nevertheless, we may not forget to highlight the fact that they are still interconnected in spite of being independent. If these theoretical assumptions are anything to go by, students might find it quite easy to link visual and verbal systems because they will be in a position to create mental lexical (through memorization) of emotions, events, objects and pictures. Consequently, students can gain better understanding and remembrance of words learned in previous lessons owing to the visual and verbal combinations (Ko, 2005). Learners can further be assisted through additional pictorial cues so that they can easily make connections between visual aids that are in form of pictures and the associated words or short phrases.

There are quite a number of past studies that have attempted to investigate and bring into perspective this probable research question. However, it is still vital to dig deeper and investigate a more effective mode of multi-mode gloss. This implies that the aspect of vocabulary acquisition and multimedia gloss is still a fundamental area of study that needs to be expanded even further.

Bilingual Lexicon

A better way of comprehending the effectiveness of L1 and L2 glosses is through examining the manner in which concepts and individual words are mapped out during the process of learning. The mapping process takes place in the mind of the learner. There are a number of lexical models that can be used to attain this objective. However, before the models can be used, it is crucial for the teacher to appreciate the fact that the learner’s mind is supposed to be occupied by a bilingual presentation of two different languages (Yoshii, 2006). The most common frameworks that can be used in this case include the concept mediation and words association models. The mediation of L2 is only possible via L1 according to the words association model. The argument behind this claim is that close relation exists between L2 and L1 words and phrases. Yoshii (2006) established that the concept mediation model arose from word association model even though the transition has taken quite a long period (Yoshii, 2006).

The mental lexicon means that part of semantic memory (where the concepts store is found) processes interactively and in a parallel manner, the information provided by every word (which may be graphical, phonological, morphological, syntactic or semantic). These processes take place during reception and linguistic production and articulate the concept and meaning of words at different levels depending on the nature of the cognitive task, which is being undertaken at given time. However, it is imperative to have a broader view (not just restricted to language) of the mental lexicon. According to Rott (2007), it is far from being an isolated module that is exclusively focused on language processing and independence of thought (Rott, 2007).

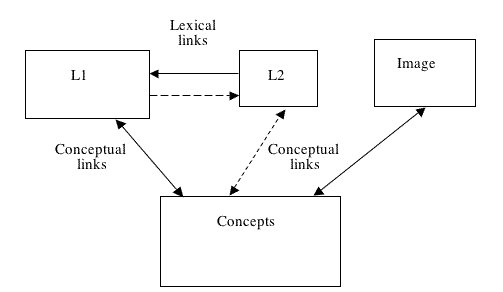

During the early learning stages, lexical links or word-to-word links are the main dependent factor for L2 learners. However, they are in a position to execute conceptual links more effectively as their proficiency in L2 improves since their application depends on the links available. Consequently, the conceptual mediation model alongside its associated links as well as the lexical links were later revisited and revised by Rott in the year 2007 with the aim of creating a vivid understanding of the two extremes. The strengths portrayed by the conceptual links have so far been delineated. As it stands now, there is a revised model that can cater for all research findings of the recent years. This new model makes use of an image in order to improve clarity and comprehensiveness (Kroll & Sunderman, 2003). However, it should be understood that even the new model has a strong background in the old models because it is still used to access meanings of words at the initial stages of L2 vocabulary acquisition. In addition, as the proficiency of a learner increases, L2 words can be easily correlated to conceptual links (Kroll & Sunderman, 2003).

The model shown below is very instrumental in this research study. One of the main reasons for preferring this model is its adequate theoretical background. In addition, the model pre-empts the notion that L2 gloss is less effective than L1 gloss when passing the knowledge on new words to learners. In this case, L1 exhibits a rather stronger link when it comes to word-to-concept linkages. Most learners who may benefit from this connection are those who may be described as intermediate learners (Rott, 2007). The dual coding hypothesis also comes in handy in this discussion bearing in mind that the model makes use of it in a number of ways. Conceptual linkage also benefit from the fact it has another source which is related to images since its application involves relating different links. In the end, such a connection is capable of enhancing the relationship between concepts and words (Laufer & Hulstijn, 2001).

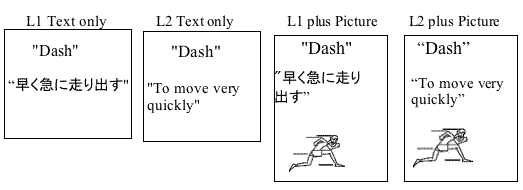

From the above figure, it is evident that in the due process of relating L2 and L1 language acquisition and learning, the conceptual link plays a major role. In other words, the methodology used to pass knowledge should be associated with the concept desired during the process of learning. In addition, both the conceptual and lexical links are required in order to create a complete loop of process that L1 and L2 learners require when gaining knowledge on new words (Laufer & Hulstijn, 2001). The figure clearly represents a revised hierarchical model that takes into account all the recent changes to language acquisition and learning since the links are clearly correlated in the model. As can be seen, the model contains an image as a crucial learning and teaching aid. The figure below also shows the different types of glosses with respect to L1 and L2 (Rott, 2007).

Research questions

RQ 1: are L1 or L2 glosses more effective when acquiring new word meanings during reading?

RQ2: are L1 or L2 glosses more effective in the retention of new words acquired during reading?

Methodology

Participants and design

A total of 18 Arabic learners of English were given a reading task as part of their normal classes. For 9 students, the text had glosses in L1 (Arabic). For the other 9 students, the text had glosses in L2 (English). Learners’ knowledge of these items were tested immediately after the reading and again two weeks later. The study was conducted in a secondary school in Kuwait. In order to choose the participants the teachers were asked to select their best students in reading in the English classes. This action was taken to ensure that the collected data would be valid and the only tested variable would be the efficacy of the language of the gloss not the students’ levels. All students were given a consent form to be signed by their parents with an Arabic explanation of the study. Before the study began, students were given a pre-reading vocabulary knowledge test to decide which words to include in the study. It was substantial for the legitimacy of the study that all students do not know the words being tested. The words targeted in this test were (valley, chambers, archaeologist, inexplicable, cursed, sceptical, frivolous, inscriptions, catastrophes and priestess) The researcher tested if the students do not know the words being tested through application of the vocabulary test (Chen, 2002).

Variables

In this analysis, the reading was done from hardcopy material and not from the Internet. Therefore, the rest of the study will largely concentrate on the text type of the gloss. On the other hand, the scores obtained by learners were the dependent variable. In this case, whatever they scored largely depended on a number of factors such as whether they had understood the concept in class, individual abilities of learners and the complexity of the test given. Definitely, difficult vocabularies that are not within their reach would translate into poor scores. Moreover, the ability to recognize and apply the right vocabulary was instrumental in the assessments.

Instruments

Pre-test

The pretest was taken by learners two weeks before the actual treatment date. A vocabulary knowledge test was made up of 50 multiple choice questions. Learners were expected to select the correct answer from the choices given. It was also clear that the vocabulary knowledge test was designed for research purposes only. The learners’ teachers were not allowed to view the final marks or results of the assessment. Moreover, the test marks were not to be included in the students’ school report. The learners were informed to mark against the answer which they perceived was right (Kroll & Sunderman, 2003).

In order to be ready to answer the questions, learners who took part in this study were requested to read a 400-word short story document. During the process of reading, they were also supposed to be on the lookout for certain key words in the given piece of reading. The total number of words targeted were 10. In the research work, solid verbs were employed. This was necessary because the researcher wanted to demonstrate them in the most effective manner. In regards to the learners who took part in this study, the words used were not cognate (Laufer, 2001).

Post-test

In order to achieve the best and valid outcomes from this research study, the posttests given to the participating learners were two in number. In other words, there was the first posttest and the second posttest. The two posttests were carried out within a difference of two weeks. There were a total of ten questions in each posttest (Ellis & He, 1999). The authenticity of both posttests was enhanced by making sure that the participants were not aware of the nature of coming tests. Each of the posttest required the learners to fill the blank spaces with words given in the box. In addition, both posttests had the same format. However, they were unique from the pretest. For every right feedback by a learner, a score was awarded. Since their teachers were not supposed to be part of the process, another proficient bilingual speaker and the researcher examined the responses given by the learners. They also rated each student based on individual scores. The two raters consulted each other whenever there was need to do so before awarding points. It was not a difficult task to mark the tests because it only involved picking the right answer (Karp, 2002).

Results

The test results obtained from both tests are shown in the table below. The scores were out of 10.

Some of the results improved after taking the second post reading test, so the researcher interviewed the students who improved their score. A couple of the students claimed that they have made a list of the new words and written their meanings in Arabic to help them memorize the words. Another student said that she has written all the words in sentences to help her memorize the them.

Discussion and analysis

This study sought to answer whether the acquisition of new word meanings during the reading process is effective with L1 or L2 glosses. From the results tabled above, the overall results improved in the second tests for both English and Arabic. This corresponds to the conclusions made in other past studies whereby students tend to perform better when a test with similar or same metrics is repeated. As already hinted out in the literature review section of this study, most learners often prefer to either memorize or write down new concepts or words so that they can be fluent in them later. However, the results also indicate that there is no remarkable difference between in text-only glosses between the first and second language acquisition (Ghabanchi & Ayoubi, 2012).

Even if vocabulary learning is enhanced, either L1 or L2 did not show effectiveness of gloss. Hence, this research study yielded the expected standard outcomes that incidental vocabulary learning cannot be affected by the type of language while glosses still remain to be a useful tool. Incidental learning may have significantly affected the effectiveness of L1 against L2. For example, the meanings of words are incidentally selected by students without careful thought. This does not improve the rate of learning by any margin. In addition, the period of two weeks was not enough to construct adequate conceptual links bearing in mind that it was the first time the researcher was being exposed to the students. If L1 is used for a long time and in a consistent manner, it is highly likely that it can be more effective than L2. In this regard, the length of the study could not permit the analysis to reach that level. Hence, the merits and effectiveness of L1 glosses can only be realized after a significant period.

When speaking and reading, we activate the mental lexicon automatically and unconsciously. Then we may ask ourselves how the vocabulary is represented in the mental lexicon (Kroll & Sunderman, 2003). Studies with children during the process of acquisition of the mother tongue show that speech presupposes procedural representations (Hauptmann, 2004). Better still, the representation of cognitive element triggers an articulation scheme, which results in the formulation of a phrase. For this reason, any communication intent in the L2 class will activate, the learner. This explains the inevitability of interferences, and especially the need to develop from learners’ level of knowledge (Rott, Williams & Cameron, 2002)

One of the first steps of discovering the meaning of a lexical unit consists in looking for clues (cues) in the text or in their vicinity. Experiments carried out in this field, accompanied by recording of thought followed by high voice looking back have revealed that while some learners (typically beginners) have a tendency of looking for these clues at the micro level, they process the information in the bottom-up direction composed of smaller units for the whole of the text. Learners who are more advanced prefer working top-down, starting the whole text and context and move towards resolving the item in question (Rott, 2005).

In the second research question, this research study sought to answer the question whether L1 or L2 glosses were more effective in the retention of new words acquired during reading (Kroll & Sunderman, 2003). From the results table and after interviewing a few learners who improved their scores in the second test, it was vivid that L1 glosses were more effective than L2 glosses bearing in mind these learners were already more familiar with the vocabulary words in English. Although English was the second language in this case, most learners who excelled in the second posttest asserted that they memorized the words and also wrote them down in order to assist them in recalling Arabic synonyms.

For learners who performed poorly in the second posttest compared to the first posttest, it can be argued that this exercise came at a time when they were not prepared to sit for such examinations. In other words, the experience was a form of interference to their normal learning programs. In inference, it is not only a matter of testing the sensitivity language of the learner, but rather to provide the activation of complex processing operations which interacts with declarative knowledge. This requires some cognitive effort in order to reach acceptable and reliable results. Certainly, the learner may remember meanings of words that were found through personal efforts more easily than the ones that were simply acquired or taught by another person (Hulstijn & Laufer, 2001). This explains why students who performed well in the second posttest individually decided to memorize and even write down the vocabularies for the sake of future reference. Therefore, spontaneity revealed by the learner in his discovery process may be supported or undermined by a series of factors ranging from linguistic clues to elements of their knowledge of the world, the language declarative knowledge and its context and co-text – which must be activated at all times (De Ridder, 2002).

Conclusion

The degree of efficacy of various classes of glosses was examined in this study. In particular, the research study laid a lot of emphasis on the aspect of incidental vocabulary learning in regards to the acquisition and learning of second language (L2). Both L1 and L2 have been compared and contrasted in this research study with the aim of ascertaining the efficacy of two main components namely the first and second language acquisition. After carrying out an empirical research study in a secondary school in Kuwait, it was still difficult to establish stark or outstanding differences between the two types of glosses. As much as the bilingual lexicon model remains to be a reality owing to the past comprehensive studies in this linguistic field, this brief project could not ascertain some the expected facts owing to the short period within which the study was conducted. For example, the research took a period of two weeks before it could be completed. It is fundamental to assert that conclusive findings could only be obtained by running the research study for a period of about 3 months.

When the first and second posttest results are compared, it can be seen that some learners scored poorly in the second when compared to the first test. This is a clear indication that forgetting rates are different across the board. As much as this research study cannot firmly establish a more effective type of gloss, it is precise to confirm that both L1 and L2 glosses play vital roles in the process of incidental vocabulary learning. In other words, they are equally useful.

Under Arabic education, recognition mode is structured and hence, the mental lexicon is extremely important. It is also vital to comprehend how to stimulate the process of language acquisition, retention and understanding the meaning between the two extremes in order to provide explicit and immediate translation. Better results can be obtained if learners are led into a process of discovery. This process calls for both procedural declarative knowledge so that the learner can develop inference strategies to help in establishing a link between the input and the corresponding mental representation.

Both the processes of teaching and learning new words have a direct bearing on the outcomes of this research work. To begin with, a learner’s incidental vocabulary can be enhanced either in L1 or in L2 irrespective of the type of gloss used. It is also highly advisable to embrace the use of glosses in materials set aside for reading purpose. With the passage of time, the degree of effectiveness on the gloss used may begin to surface or be seen. The processes of researching and teaching vocabulary demand the application of glosses because the former usually take a long time to accomplish. It is also interesting to learn that detecting differences between L1 and L2 glosses requires long-term effects of a similar research study.

References

Chen, H. 2002, Investigating the effects of L1 and L2 glosses on foreign language reading comprehension and vocabulary retention, Computer-Assisted Language Instruction Consortium, Davis, CA.

De Ridder, I. 2002, “Visible or invisible links: Does the highlighting of hyperlinks affect incidental vocabulary learning, text comprehension, and the reading process?”, Language Learning & Technology, vol. 6, pp. 123–146.

Ellis, R. & He, X.1999, “The roles of modified input and output in the incidental acquisition of word meanings”, Studies in Second Language Acquisition, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 285 -301.

Gardner, D. 2007, “Children’s immediate understanding of vocabulary: Contexts and dictionary definitions”, Reading Psychology, vol. 28, pp. 331–373.

Ghabanchi, Z. & Ayoubi, E.S. 2012, “Incidental Vocabulary Learning and Recall by Intermediate Foreign Language Students: The Influence of Marginal Glosses, Dictionary Use, and Summary writing”, Journal of International Education Research, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 85-88.

Grabe, W. & Stoller, F. 2004, Teaching English as a second or foreign language, Heinle & Heinle, Boston.

Hauptmann, J. 2004, The effect of the integrated keyword method on vocabulary retention and motivation, University of Leicester, London.

Hulstijn, J. H. & Laufer, B. 2001, “Some empirical evidence for the involvement load hypothesis in vocabulary acquisition”, Language Learning, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 542–545.

Hulstijn, J. H. 2001, Cognition and Second Language Instruction, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Karp, A. S. 2002, Modification of glosses and its effect on incidental L2 vocabulary learning in Spanish, University of California, New York.

Ko, M. H. 2005, “Gloss, comprehension, and strategy use”, Reading in a Foreign Language, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 125-143.

Kroll, J. F. & Sunderman, G. 2003, Cognitive processes in second language learners and bilinguals: The development of lexical and conceptual representations: The Handbook of SLA, Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA.

Laufer, B. & Hulstijn, J. 2001, “Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language. The construct of task-induced involvement”, Applied Linguistics, vol. 22, pp. 1–26.

Laufer, B. 2001, “Reading, word-focused activities and incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language”, Prospect, vol. 16, pp. 44–54.

Mondria, J. 2003, “The effects of inferring, verifying, and memorizing on the retention of L2 word meanings: An experimental comparison of the “meaning-inferred method” and the “meaning-given method”, Studies of Second Language Acquisition, vol. 25, pp. 473-499.

Rott, S. 2005, “Processing glosses: A qualitative exploration of how form-meaning connections are established and strengthened”, Reading in a Foreign Language, vo. 17, pp. 95-124.

Rott, S. 2007, “The effect of frequency of input-enhancements on word learning and text comprehension”, Language Learning, vol. 57 no. 2, pp. 165-199.

Rott, S., & Williams, J. 2003, “ Making form-meaning connections while reading: A qualitative analysis of word processing. Reading in a Foreign Language, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 45-75.

Rott, S., Williams, J., & Cameron, R. 2002, “The effect of multiple-choice L1 gloss and input-output cycles on lexical acquisition and retention”, Language Teaching Research, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 183-222.

Yoshii, M. 2006, “L1 and L2 gloss: Their effects on incidental vocabulary learning”, Language Learning & Technology, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 85-101.