Executive Summary

FDI investment in the automobile industry is a looming trend due to the increasing cost of production in developed countries. So, we target emerging economies that provide new markets of opportunity as well as incredibly lower production costs. For the research of our car company, we chose two countries, Poland in Eastern Europe and Thailand in South-Eastern Asia. The reason for choosing Poland is because, research and previous studies have shown that even though its FDI inflow has been declining in a climate of economic and political risks, automobile companies have always preferred Poland to any other European country. It has attracted FDI from automobile companies like Fiat, GM, and Daewoo. The reason behind choosing Thailand is its emerging attractiveness in the automobile foreign investment from companies like Ford, Honda, Nissan, etc. Thailand’s liberal economic policies and increasing export of automobiles provide a clear indication of its success as an investment destination for foreign capital. Further Thailand has a high degree of ease of doing business.

Our comparative analysis shows that Thailand wins over Poland in the current scenario for an FDI in the automobile sector, especially for a company like ours, which is aiming to expand the market to an area with rising demand for cars as well as a country that can provide an environment for low-cost production.

Introduction

In this paper, we analyse the comparative lucrativeness of FDI investment for our Automotive Company in Poland and Thailand, which are two emerging economies in Eastern Europe and South East Asia respectively. To analyze which country will be more advantageous for our investment we apply a few strategic analysis tools like the PESTLE analysis to understand the country’s compatibility for the particular industry and Porter’s Diamond analysis to see the country’s environment. Apart from these tools we use various statistical data to compare both the country’s and determine their comparative advantage for this particular industry.

First, we will try to explain why we considered the two countries viz. Poland and Thailand for our FDI considerations. As we are a car producing company (automotive industry) we did a quick survey of the countries in Eastern Europe and southeast Asia. While considering a country for FDI we need to consider the following: low transaction costs, low risks for investment, a developed capital market, assured property rights, high expenditure in research and development (R&D), a highly developed infrastructure, a liberal economy, a lack of barriers for the entrance or exit from the market, a high quality of institutions supporting entrepreneurship and innovations, low taxes for employees, highly qualified specialists, a big domestic market, positive perspectives for the development of the country and political and social stability. The attractiveness of the automotive industry can be increased by additional factors: the number of automotive suppliers qualified by ISO 9000/2000 or TS 16949, the proximity of car manufacturers, the access to raw materials, a good climate guaranteed by the government, operational clusters and co-operation between the industry and universities as well as R&D institutions and consulting companies.

After researching the latest reports on the FDI attractiveness of Poland for the automotive industry it is evident that the Polish economy is performing not as well as other Eastern European countries. However, the attractiveness of the Polish automotive industry is high estimated – especially since joining the EU. For example, an Ernst &Young report (2005) described Poland as one of the top 5 countries most attractive for the automotive industry in Europe. That is why we chose Poland in the Eastern European region. The reason why we chose Thailand is similar. Thailand, also known as the “Detroit of Asia” is the largest car producer in the region, it is ranked 9th in the world car production (KPMG Report, ASEAN Countries, Automotive Industry, 2005). So, both the countries were clear choices for our consideration of FDI.

Table 3 shows a comparative study of the key economic indicators of the Polish and Thai economy. The figure is an average of 2003-07 data. Though Thailand’s GDP growth is more than that of Poland but in total terms it is half of that of Poland. Further, per capita income too is much lower for Thailand. This indicates that Thailand is a country which is poorer than Poland. But its growth rate is stronger. Further if we consider the population growth rate Poland is experiencing a downward spiral in population growth like most of the European countries. Further it has a growing percentage of old people in the population. Poland’s declining birth rate and aging population will lead to major changes for Polish society. It is estimated that Within 30 years, one-third of Poland’s population will be more than 60 years old. (ISA Report 2008) Whereas Thailand is experiencing an increase in population growth rate, with 70 percent of its population within the age group of 15-64 years. (www.boi.go.th) this clearly indicates that Polish economy is facing a labour problem whereas Thailand’s economy does not have a labour problem at all. Historical average inflation of Poland is at 2 percent and that of Thailand at 3.2 percent, which indicates that both the country’s price indexes are almost equally stable. FDI flow in Poland has been higher in Poland than that in Thailand.

Doing a more detailed analysis of the economic indicators of both the countries we look at a few other key economic indicators (See Appendix, Table 1 and 2). For instance, the exchange rate stability can show a lot about the economy’s fundamentals. Thailand as well as has shown an appreciating and stable currency. But Poland’s stability of currency may be attributable due its membership in EU but that of Thailand is due to purely strong fundamentals and increasing industrial base. Further considering both the country’s current account balance, Poland has a negative current account balance indicative of more outflow than inflow of foreign currency, which shows the economy’s weakening situation, whereas that of Thailand is strong. So, we may say, even though in absolute GDP terms Poland is stronger than Thailand, in terms of smaller economic and social indicators, Thailand is ahead of Poland.

We see that the FDI flow in both the countries has been rising. But that of Poland is much higher every year than that in Thailand. Overall ranks given by World Bank to countries as largest receiver of FDI in automotive industry, Poland ranks fifth and Thailand ranks twelfth. If we compare the contribution of automotive FDI as a percentage of total FDI of Thailand to that of Poland we see that the former is just 8.4 percent and the latter is a whopping 40 percent.

The FDI trend in post-Asian Crisis era was mostly characterized by an increase in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) as foreign firms took over Thai companies that faced severe debt and liquidity problems. In terms of the contribution of M&A transactions to total net FDI flows, it is estimated to have increased from around 50-60 percent in 1998-1999 to 90% in 2000. Indications are that this massive shift to M&A activities fell almost as quickly as it rose, with much fewer deals and estimated values in 2001 and 2002. Within the manufacturing sector, the electronics industry relatively consistently attracts large volumes of FDI, amounting to 17.6 percent in 2001. For the period 1998-2000, however, electronics was overtaken by machinery and transport equipment, deriving mainly from the automotive industry, as many Japanese automotive parent companies injected capital to assist their subsidiaries and suppliers in Thailand following the crisis.

In case of Poland, though it is not a very sought-after destination for FDI in other sectors, but automotive industry still flocks to the country for investment. For example, 20% of German automotive suppliers declared that they would increase their activity in this region in the period 2006-2011 compared with 18% in Asia. The attractiveness of Poland for FDI increased after joining the EU. However, political and economic issues have generated additional barriers, which have slowed the inflow of the next big investors into this region of Europe. Investors from the automotive

industry play the main role among foreign investors. They open new factories or take over existing companies, which allows them to increase their market share and meet the requirements of their customers (mainly through the high pressure of cost reduction and high quality). This automotive FDI reflects 8% of the total FDI value in Poland and 25% of the FDI value located in the industry (Paiz, 2005). The biggest foreign automotive investors in 2005 were Fiat Auto Poland (1,6 billion USD), General Motors Corporation (1 billion USD), Volkswagen AG (835 million USD) and Toyota (507 million USD). But presently the situation is not so good. Most of the automobile investors such as Toyota and Volkswagen have stopped investing. Initially the drive for investment in this sector in Poland was due to increase in domestic sales along with exports. But domestic automotive sales are currently dwindling. So, Poland, which was once an attractive destination for automotive FDI is facing a setback.

On the other hand, Thailand’s domestic sales of automotive are increasing and foreign companies like Nissan, Toyota and Honda have the maximum market share (KPMG Report 2005). Further Thailand has an export-oriented component manufacturing sector. Global component companies like Visteon and Delphi have invested heavily in the economy. Japan too is looking at Thailand as a low-cost manufacturing base for automobiles (KPMG Report).

Further if we compare the World Bank rankings for key indicators for FDI attractiveness in table 4 we see an interesting trend. Poland – PESTLE Analysis

Table 1.

Thailand – PESTLE Analysis

Table 2.

From the PESTLE analysis of both the countries we see that Poland has a stronger total GDP but growth in GDP is higher in Thailand. But Poland is experiencing an increasing wage rate spiral, whereas that in Thailand is pretty low. Further Poland is facing the problem of diminishing population growth which will affect its workforce soon. Like other European countries, Poland too will have a workforce full of aging population. On the other hand, the scenario in Thailand is completely opposite, with almost 60 percent of its population being within the age group of 20 to 60 years. The legal situation is equally simple and advantageous for foreign investors to thrive. Politically Poland is in a more volatile situation than Thailand. Environmentally both the countries are facing a problem with pollution which needs to be addressed. So, from the PESTLE analysis we may conclude that Thailand is marginally ahead in the race to gain FDI than Poland given the current situation.

Economic Comparison

Table 3.

Table 3 shows a comparative study of the key economic indicators of the Polish and Thai economy. The figure is an average of 2003-07 data. Though Thailand’s GDP growth is more than that of Poland but in total terms it is half of that of Poland. Further, per capita income too is much lower for Thailand. This indicates that Thailand is a country which is poorer than Poland. But its growth rate is stronger. Further if we consider the population growth rate Poland is experiencing a downward spiral in population growth like most of the European countries. Further it has a growing percentage of old people in the population. Poland’s declining birth rate and aging population will lead to major changes for Polish society. It is estimated that Within 30 years, one-third of Poland’s population will be more than 60 years old. (ISA Report 2008) Whereas Thailand is experiencing an increase in population growth rate, with 70 percent of its population within the age group of 15-64 years. (www.boi.go.th) this clearly indicates that Polish economy is facing a labour problem whereas Thailand’s economy does not have a labour problem at all. Historical average inflation of Poland is at 2 percent and that of Thailand at 3.2 percent, which indicates that both the country’s price indexes are almost equally stable. FDI flow in Poland has been higher in Poland than that in Thailand.

Doing a more detailed analysis of the economic indicators of both the countries we look at a few other key economic indicators (See Appendix, Table 1 and 2). For instance, the exchange rate stability can show a lot about the economy’s fundamentals. Thailand as well as has shown an appreciating and stable currency. But Poland’s stability of currency may be attributable due its membership in EU but that of Thailand is due to purely strong fundamentals and increasing industrial base. Further considering both the country’s current account balance, Poland has a negative current account balance indicative of more outflow than inflow of foreign currency, which shows the economy’s weakening situation, whereas that of Thailand is strong. So, we may say, even though in absolute GDP terms Poland is stronger than Thailand, in terms of smaller economic and social indicators, Thailand is ahead of Poland.

FDI Trends in Poland and Thailand

Comparing the FDI flow of both countries more closely let us look at figure 2.

We see that the FDI flow in both the countries has been rising. But that of Poland is much higher every year than that in Thailand. Overall ranks given by World Bank to countries as largest receiver of FDI in automotive industry, Poland ranks fifth and Thailand ranks twelfth. If we compare the contribution of automotive FDI as a percentage of total FDI of Thailand to that of Poland we see that the former is just 8.4 percent and the later is a whooping 40 percent.

The FDI trend in post-Asian Crisis era was mostly characterized by an increase in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) as foreign firms took over Thai companies that faced severe debt and liquidity problems. In terms of the contribution of M&A transactions to total net FDI flows, it is estimated to have increased from around 50-60 percent in 1998-1999 to 90% in 2000. Indications are that this massive shift to M&A activities fell almost as quickly as it rose, with much fewer deals and estimated values in 2001 and 2002. Within the manufacturing sector, the electronics industry relatively consistently attracts large volumes of FDI, amounting to 17.6 percent in 2001. For the period 1998-2000, however, electronics was overtaken by machinery and transport equipment, deriving mainly from the automotive industry, as many Japanese automotive parent companies injected capital to assist their subsidiaries and suppliers in Thailand following the crisis.

In case of Poland, though it is not a very sought-after destination for FDI in other sectors, but automotive industry still flocks to the country for investment. For example, 20% of German automotive suppliers declared that they would increase their activity in this region in the period 2006-2011 compared with 18% in Asia. The attractiveness of Poland for FDI increased after joining the EU. However, political and economical issues have generated additional barriers, which have slowed the inflow of the next big investors into this region of Europe. Investors from the automotive

industry play the main role among foreign investors. They open new factories or take over existing companies, which allows them to increase their market share and meet the requirements of their customers (mainly through the high pressure of cost reduction and high quality). This automotive FDI reflects 8% of the total FDI value in Poland and 25% of the FDI value located in the industry (Paiz, 2005). The biggest foreign automotive investors in 2005 were Fiat Auto Poland (1,6 billion USD), General Motors Corporation (1 billion USD), Volkswagen AG (835 million USD) and Toyota (507 million USD). But presently the situation is not so good. Most of the automobile investors such as Toyota and Volkswagen have stopped investing. Initially the drive for investment in this sector in Poland was due to increase in domestic sales along with exports. But domestic automotive sales are currently dwindling. So, Poland, which was once an attractive destination fro automotive FDI is facing a set back.

On the other hand, Thailand’s domestic sales of automotives are increasing and foreign companies like Nissan, Toyota and Honda have the maximum market share (KPMG Report 2005). Further Thailand has an export-oriented component manufacturing sector. Global component companies like Visteon and Delphi have invested heavily in the economy. Japan too is looking at Thailand as a low-cost manufacturing base for automobiles (KPMG Report).

Further if we compare the World Bank rankings fro key indicators for FDI attractiveness in table 4 we see an interesting trend.

Table 4.

Table 4 shows the skill base required for automotive production; Poland ranks higher than Thailand. One explanation for this may be that Poland being an old operator in this field has accumulated more skilled labour for the industry. The same reasoning can be given for Poland ranking higher in R&D. But one down turn in this is that Poland has an aging workforce. But in other areas Thailand is a close contender. In case of labour cost, Thailand in much lower than Poland. This shows that investing in Thailand will give us the advantage of extremely low labour cost.

Porter’s Diamond Model

As we are looking at the international relationships and comparisons between Poland and Thailand and their attractiveness for FDI we have to think about international competition and the role that nations and resources play in it. For this we employ a model developed by M. Porter. This model provides a new perspective, tools and a new approach to competitiveness that grows directly out of an analysis of international successful industries. Porter underlines that, in a world of increasingly global competition, on one side a nation’s competitiveness depends on the capability of its industry to innovate and upgrade, on the other hand competitive advantage of the Companies is created and sustained by differences in home environment (that include values, culture, economic structures, institutions, history and so on).

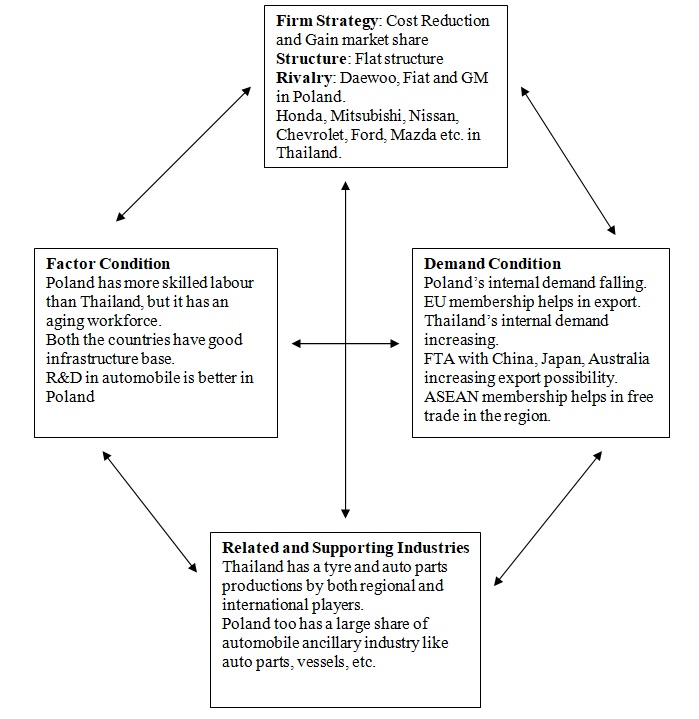

As a company our main reason for divesting in FDI in another country is to gain larger market, cost advantage and retain our competitive advantage. On the basis of the model we see that Porter’s Diamond has the following attributes:

- Factor Conditions: The nation’s position in factors of production, such as skilled labour or infrastructure, necessary to compete in a given industry.

- Demand Conditions: The nature of home-market demand for the industry’s product or service.

- Related and Supporting Industries: The presence or absence in the nation of supplier-industries and other related industries that are internationally competitive.

- Firm Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry: The conditions in the nation governing how companies are created, organized, and managed, as well as the nature of domestic rivalry. These determinants create the national environment in which companies are born and learn how to compete.

Doing a diagrammatic comparison of both the countries on the basis of the factors indicated by Porter, we see a distinct trend towards preference towards Thailand. Let us study the diagram, figure 3. For both the countries our strategy remains the same. In case of Factor condition, we see that Poland has more skilled labour and technological support to sustain an industry than Thailand, but that in Thailand in developing rapidly. What is most advantageous about Thailand is its low cost of labour, technology, land, capital, etc. Poland’s demand for automobile is dwindling. EU membership opens the gate for export in whole of Europe. Thailand’s demand for cars is increasing. FTA are also increasing possibility of export to other countries like Australia, China, Japan along with ASEAN membership it has the whole Asian market at disposal where the demand for automobiles are increasing rapidly.

Both Poland and Thailand have related supporting industry, but Thailand has a bigger edge, for its world class rubber production which aids tyre production and investment of international auto parts manufacturers. On the other hand, in Poland, most of the auto ancillary industries are local companies.

So, a comparative analysis reveals that though Poland has a sustained record of automobile FDI flow in the country, but Thailand is catching up faster. It is providing greater avenues of market expansion and low-cost production as is the strategy we adopt for FDI in a country. Moreover, Thailand will provide us the opportunity for innovation.

Conclusion

To summarize we do a SWORT analysis of both the countries and show which is a better option fro FDI investment.

Clearly among Thailand and Poland the later has a stronger fundamental and current trend to support FDI in automobile. This is so because Poland though a lucrative destination earlier, has started experiencing a downturn in automotive FDI. One reason can be slowing growth rate of domestic demand and increasing cost of production. Whereas Thailand, though a new entrant has attracted a lot of FDI with its open policy system which enables foreign investors to access a new market.

Appendix

Table 5.

Table 6.

References

Porter, Michael E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Free Press: 1990.

“Republic of Poland: Selected Issues” IMF Country Report No. 08/131,. 008.

Private Sector at a Glance, World Bank Report.

Investing in Poland, Ernst and Young Report 2007.

Murgasova, Zuzana “Post-Transition Investment Behavior in Poland: A Sectoral Panel Analysis”, IMF Working Paper 2005.

Campos, Nauro F. and Kinoshita, Yuko “Foreign Direct Investment and Structural Reforms: Evidence from Eastern Europe and Latin America” IMF Working Paper 2008.

Doing Business in Poland, Ernst and Young report, 2007.

Country Report Poland, International Strategic Analysis (ISA), 2008.

Regional Economic Outlook, Asia and Pacific, IMF 2008.

Automotive and Components Market in Asia, KPMG Report, 2005.

Thailand Economic Monitor, World Bank Report 2008.

Country Assistance Strategy the Kingdom of Thailand, World Bank Report, 2003 Southeast Asia.

Doing Business 2008 Thailand, A Project Benchmarking the Regulatory Cost of Doing Business in 178 Economies, World Bank Report 2008.