Introduction

According to the Australian National Training Authority (2001), post-compulsory education forms an important component of Australian economic, social and cultural development. Historically, Australia has experienced periods of economic development due to the willingness of the government to adopt policies to fuel development. Some of these were the economic reforms that were implemented by the Hawke government in the 1980s and the economic reforms implemented by the Keating governments in the 1990s. With time, the government got convinced that “there is a link between education and training and economic security and prosperity” (Kirby 2000, p. 3).

This created a necessity to implement policies that would make education in the country exemplary and that would contribute to its economic development and prosperity. This resulted in compiling the Ministerial Review of Post Compulsory Education & Training Pathways the aim of which was to review the participation of young people in post-compulsory education and educational outcomes for them, as well as to offer recommendations to improve the current situation with education in the country (Kirby 2000). The report has addressed a wide range of issues and challenges by which current compulsory and post-compulsory education can be characterized.

It has placed special emphasis on the issue of social inequality in education and the consequences of this inequality for students of low socioeconomic status and their academic achievements in particular. The challenges that the review has identified are related to discrimination of students based on their academic achievements, influence produced on the students’ academic achievements by their socio-economic status, and unequal access to post-compulsory education for young people.

The policy challenges identified by the Ministerial Review of Post-Compulsory Education and Training Pathways in Victoria are to increase participation rates in post-compulsory education, to ensure equal access of different layers of the population to post-compulsory education, to avoid improper outcomes in education that can lead to unstable economy in the country, and to make lifelong learning effective and to prove its necessity for further education and employment; the review proposed several reforms to improve the situation and some of these reforms have been enacted by the government, though there remain areas which could have received more attention in the review because it did not give proper account of vocational education and training in schools and intervention into early school leaving, as well as no clear strategies have been provided to increase the rates of school participation and completion.

Challenges to Policy Makers

Discussing three major challenges identified by the Ministerial Review of Post-Compulsory Education and Training Pathways, it is worth mentioning that they all are interrelated and can be best understood if they are discussed from the perspective of social inequality within the system of education.

Firstly, it should be mentioned that everything roots in discrimination with regards to the students’ level of academic achievements. This problem has serious implications for all three challenges under consideration. Thus, for instance, participation in post-secondary education depends much on the admission of students to higher educational establishments, universities in particular. According to the report, participation of young people in education in Victoria is much higher than in other Australian states, but, compared with international standards, it is still rather low (Kirby 2000). This is largely connected with the fact that low graders do not often consider the opportunity to get post-secondary education, especially that provided by the universities.

It is well known that grades serve as a primary factor for admission to the universities this is why low graders constitute the majority of those who are not accepted to the universities: “Around 50 per cent of the lowest achievers aim for higher education, but their offer rate plummets to 12 per cent” (Kirby 2000, p. 69). This is why the majority of the low graders choose tertiary education, mainly TAFE (Technical and Further Education).

As stated in the report, the biggest part of VCE students with low grades consider TAFE as their only possibility of post-compulsory education; more than 45 per cent of them aim for TAFE in comparison with 0.5 per cent of those who have high academic achievements (Kirby 2000). This testifies to the fact that students’ ability to get higher education is judged by their achievements at school, which is discriminating because several students start performing better academically in university after the years of being low-graders at school.

Secondly, the problem of discrimination based on academic achievements also spreads to the challenge of ensuring equal access to education for different layers of population. The matter is that poor academic achievements have a direct relation to the students’ low socio-economic status, which creates an idea that it is not always that the schools can help the students realize their full potential (Young Victorians on Track for the Future 2007).

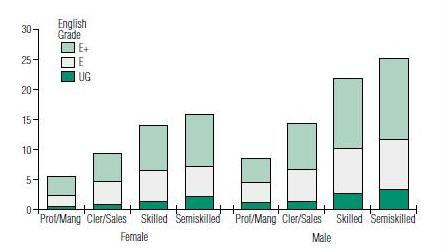

Students with lower SES, for instance, have less access to educational facilities and, therefore, less intellectual stimulation, as well as “socio-economic status seems to influence a student’s attitudes, interests, values, motivations, etc. and thus academic accomplishment” (Deka 1998, p. 22). This results in studying being more complicated for them than for students from the families with higher social status. Figure 1 illustrates this relation between socioeconomic status and students’ grades in a particular subject (English, in this case):

This figure reveals that that there are significant differences in grades achieved by students of different socioeconomic backgrounds. This points at the inequality within the system of education and creates considerable problems with regards to students’ further life. If viewed on a larger scale, inability of the students with SES to study on the same level with students whose SES is higher results in the former’s low level of general academic performance and, as mentioned earlier, inability to access higher education.

Consequently, such discrimination in education leads to the increased number of students oriented towards tertiary education (Perry & World Bank 2006); this further entails a decrease in the rates of those who are enrolled into universities and who become highly qualified professionals, which is then reflected in the overall economic performance of the country.

Besides, unequal access to education leads to a problem of early school leaving which is also typical for low achievers and students with low SES. As noted by Kirby (2000, p. 48), “each year in Victoria approximately 11,000 young people leave school without any recognized qualification.” This part of students enters labour markets but, of course, cannot occupy highly-paid positions. The main contributors into this number of early school-leavers are low achievers and students with low SES (Kilpatrcik, Abbott-Chapmann & Baynes 2002).

Low SES is characteristic for the majority of early school-leavers (55 per cent) who have two primary reasons to refuse from completing school: first of all, they are more interested in earning money than in getting any education; the second reason is their poor attainment at school (Stanley 2007) which, as the students are aware, will not let them get higher education with the tertiary education remaining their only choice. Early school-leaving is a considerable problem because it is fraught with serious consequences for students:

Research in Australia and overseas shows that early leavers are more likely to become unemployed, stay unemployed for longer, have lower earnings, and throughout their life accumulate less wealth […] They also more often experience poorer physical and mental health, higher rates of crime and less often engage in active citizenship. There are also social costs associated with increased welfare needs. (Lamb n.d., p. 23)

Ensuring equal access to education can help some students to avoid these problems. This is why the challenge of making students interested in completing at least compulsory education is emphasized in the report under consideration. Moreover, this problem has further implications on one more challenge identified in the Ministerial Review of Post-Compulsory Education and Training Pathways.

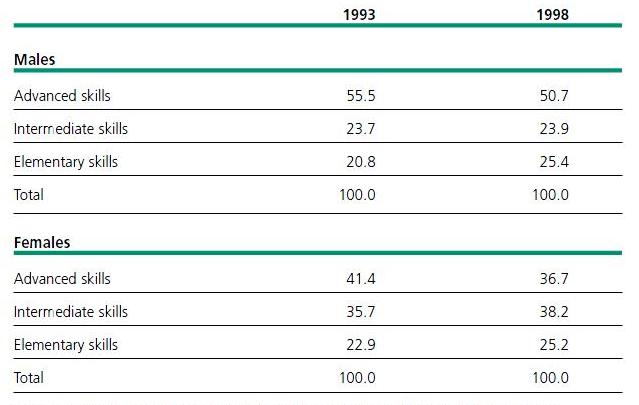

This challenge is to avoid the outcomes in education that can hamper the economic growth and development of the country. As it can be seen from everything mentioned above, discrimination in education with regards to low academic achievements, as well as low SES is directly related to the economic stability of the country. First of all, discrimination and social inequality result in fewer students getting specialized education, which inevitably leads to considerable reductions in the amount of highly skilled and educated labour force. This is a serious problem for Australian labour market where the demand for highly educated occupation groups has been increasing since the mid-1990s (Stanley 2007). As presented in Figure 2, there was a high demand for advanced skills already in 1993-1998:

Unfortunately, TAFE cannot ensure the country with qualified administrators, managers, and similar professionals that will represent the majority of employment in the coming several years. The main problem consists in that training such professionals demands much time and costs, as well as special educational programs that will ensure the students with sufficient level of work experience before they will be able to fulfil their roles effectively (Stanley 2007). This is why entering higher education is crucial for the Australian students and Australian economy.

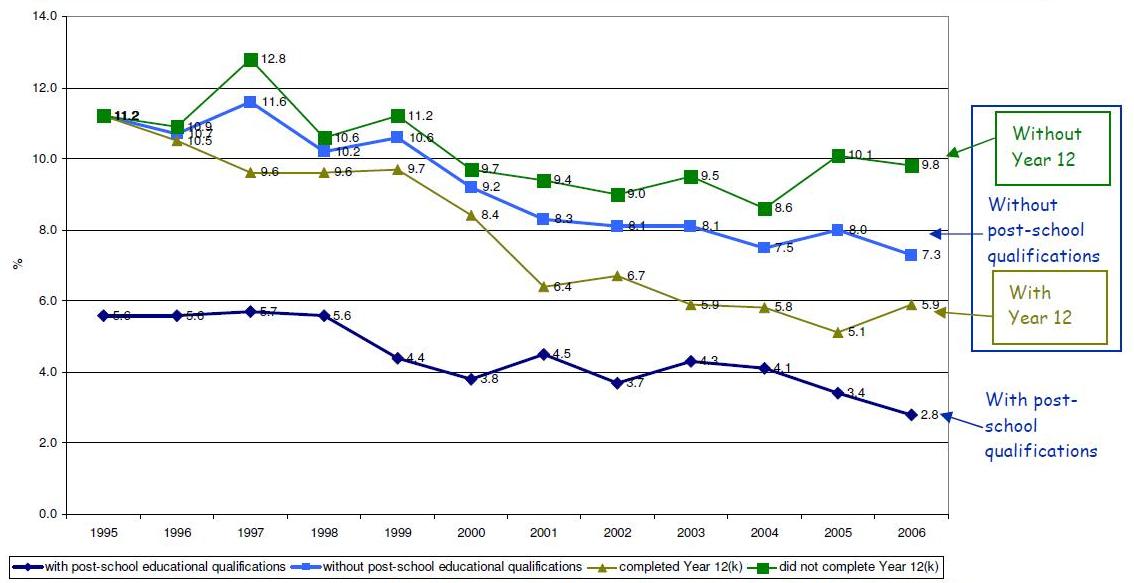

And, secondly, discrimination and social inequality lead to the increased number of early school-leavers (Kirby 2000); this results in the increased levels of unemployment, which is also not contributing into the economic success of the country. As emphasized by Kirby (2000, p. 37), “the unemployment rate of 10.8 per cent for those who did not complete secondary schooling or obtain a post school qualification is much higher than for other persons with some form of qualification.”

The increasing number of premature school-leavers leads to the wastage of employment. For instance, according to the data obtained in 2004, early school leavers constituted 60% of those who were not engaged in full-time work or learning, while only 16% were constituted by those who completed Year 12 (Stanley 2007). This testifies to the fact that namely early-school leavers contribute into high levels of unemployment.

Another group of those who create unemployment is presented by those who did not manage to complete post-secondary education. As mentioned by Volkoff and Walstab (2007), post-school qualification did not contribute much into the unemployment rates, as well as no considerable contributions into unemployment were observed from those who did not complete Year 12; however, already in 2005, the completion of Year 12 was proven to ensure the 4 per cent reduction in the rates of unemployment. Figure 3 illustrates that unemployment threatens more to early school-leavers and to those without post-school qualifications (these data are related to Victorians):

Thus, economic instability is caused by inability of the labour force to meet demands of the employers with regards to high skills required for modern professions, as well as by low rates of retention in high school and post-secondary education which lead to high rates of unemployment. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the retention rates to ensure the lower level of unemployment in Australia and to contribute into the country’s economic growth and stability, which is one more challenge identified by the review.

And lastly, all these issues are related to the final major challenge identified by the Ministerial Review of Post-Compulsory Education and Training Pathways. Kirby (2000, p. 49) mentions that “much depends on whether the individual continues in training and whether an adequate basis for lifelong learning has been built either during school or in post-school training.” Viewing this relation from the generalized perspective, each of the issues discussed above has certain influence on the students’ attitudes towards lifelong learning.

Thus, for instance, discrimination with regards to poor academic performance may result in the unwillingness of the student to continue education and to pay attention to lifelong learning in general. Attitude problems are common for low achievers and those who have been discriminated against at school, which often leads to their fear of learning due to unpleasant past learning experiences (Malone 2003). Furthermore, the attitude of people towards lifelong learning also depends on their SES; if, for instance, SES is low, a person might not be able to continue education because of financial problems or owing to being busy at work.

Similarly, early school-leavers do not have a chance to continue education because they have to work. As a result, the majority of those who did not continue education did not acquire necessary skills and knowledge enabling them to move to the higher stage in the transition process.

However, what is more important is that proper attitude to lifelong learning ensures better educational and employment opportunities. The importance of this attitude is emphasized by McKenzie (2000, p. 2) who turns special attention to lifelong learning in the modern world oriented towards constant development: “The pace of economic and social change is so rapid that young people will need to acquire new skills and knowledge throughout their adult lives to maintain their employability and capacity to engage effectively in society.”

Proper attitude towards learning guarantees that a student will be more oriented towards engaging in higher education and obtaining the qualification that will contribute to his/her lifelong learning, because the majority of the modern professions require constant upgrade of skills and knowledge in contrast to jobs demanding intermediate or elementary skills. Therefore, the review under consideration considers it its final challenge to ensure continuity between education and training, as well as smooth transition between different pathways, which will guarantee lifelong learning for every Australian student.

The Lines of Reform Proposed by the Review

After identifying and describing major policy challenges, the Ministerial Review of Post-Compulsory Education and Training Pathways has proposed several recommendations to address these challenges. Much attention has been paid to the issue of social inequality and the necessity to ensure the students with special needs with proper level of compulsory and post-compulsory education, as well as guarantee their access to lifelong learning and development. In total, 31 recommendations were proposed by the review and each of them paid attention to vital issues in the Australian system of education. The most important of the reforms proposed, however, was the establishment of the VQA that had to overtake several responsibilities related to the challenges identified by the review.

Since the most important reforms are related namely to the VQA establishment, it is worth grouping them into two major sets. The first set outlines the improvement of a vast area of the Australian system of education, namely the introduction of preparatory cycle before the VCE. The main task of the VQA here is to ensure that there is a sufficient number of quality programs that will make educational outcomes positive for the learners.

These programs, above all, are expected to prepare the students to smooth transition from compulsory education to work since, as stated in the review, the percentage of students who enter post compulsory education with unsatisfactory educational outcomes is rather high because some young people entering the VCE are not sufficiently prepared (Kirby 2000). Partially, this is the result of their history of educational failure, while another explanation is the school environment that is not suiting for some groups of students:

There is several groups of young people who find schools to be an uncomfortable setting, or whom schools find it difficult to accommodate. These include young mothers, young people involved with juvenile justice, recent immigrants, and young people who suffer ill health. Koori students frequently leave school at about the Year 9 level, although many have found TAFE to be a receptive environment. (Kirby 2000, p. 80)

Therefore, the Australian system of education should focus on early educational preparation of the students for the latter to be adequately prepared for the VCE and post compulsory education. Another reason why the preparatory cycle should be introduced is the engagement of students in education.

To make the engagement possible, certain reforms with regards to school curriculum should be introduced (some of these reforms concern the changes in teaching styles concerning the students’ learning styles and supporting the teachers in developing means for student engagement). The responsibility of the VQA as far as this strategy is concerned is to implement programs oriented towards the preparation of students for the VCE and a wide range of post compulsory programs, such as VET certificates, Certificate of General Education, pre-apprenticeship programs, etc.

The second set of recommendations consists in making the VCE more flexible and consistent with the needs of the disadvantaged students (primarily, students with low SES and Koori students). With regards to increasing the VCE flexibility, it was recommended that the VQA, joining its efforts with the VTAC (Victorian Tertiary Admissions Centre), should ensure that students undertaking three and even fewer subjects could also receive an ENTER (Equivalent National Tertiary Entrance Rank) (earlier, completing four subjects was required); besides, another moderator of school assessments, apart from ENTER, should be offered to students who are unable to receive ENTER (the review proposed the General Achievement Test), as well as dual accreditation should be introduced (Kirby 2000).

Besides, school curriculum needs diversification to make the VCE more flexible. To do this, subject choice should be allowed; this will not only make the curriculum more diversified, but will ensure higher rates of participation, which is also an important challenge to address.

Dealing with special needs of some students has also been addressed by the review’s recommendations. The review recommends reintroducing technical secondary schools to make education accessible for those who are more interested in practical learning and to make the VCE accessible to the adults, unless they have no other alternatives to receive it. As far as Koori students are concerned, the review recommends delivering distant education to them, as well as making school buses and accommodation more accessible to them. Therefore, their needs have to be taken into account when developing plans aimed at improving education and training and the task of the VQA is to initiate programs that will encourage the development of such plans.

Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that the government response to the reforms proposed has been quite positive and, since the review implementation, much has been done to address the challenges that the review has identified. Among the greatest achievements was the establishment of the VQA, as proposed by the review; correspondingly, several other reforms proposed have also been addressed because they were related to the establishment of this body.

Thus, in 2001, the Victorian Government issued a legislation that established the VQA as a body that was to determine post-compulsory qualifications for schools and other institutions providing people with post-compulsory education (Praetz 2002). The VQA was expected to ensure the Australian system of education with better quality assurance system and to encourage lifelong learning, enabling people to enter and re-enter education thus acquiring new qualifications in the course of their lives. In this way, the most important recommendation of the review has been addressed.

This, however, was not the only reform enacted by the government since the Kirby Report implementation. Another recommendation to address was increasing the flexibility of the VCE. Right after the establishment, the VQA reviewed all the recommendations proposed by the report and made it its number one objective to ensure the Australian students with additional pathways. Some time after the VQA establishment, the government “had announced targets for increasing literacy and numeracy standards and for raising the proportion of those holding the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE) or equivalent to 90 per cent of young people by 2010” (Praetz 2002, 193).

Shortly after this, the last most important recommendation has been dealt with, namely, making the education accessible to the students with special needs. Therefore, ensuring participation in the lifelong learning on the part of the disadvantaged young people has been established as sub-target of the large strategy implemented by the Australian government; these young people included students with low SES, the Koori students, non-English speaking ones, rural students, and low achievers (Praetz 2002). This is how the VQA provided equal access to the VCE to all the students.

Another issue addressed was obtaining the qualification other than the VCE. The Australian government has acknowledged that diverse qualification systems could better contribute into the development of the young Australian’s vocational interests and that none of the pathways that it offered to students could guarantee them successful transition outcomes (OECD 2000). This is why it was agreed that a mix of pathways would be more beneficial for the young people, and the VET, together with the VCE, was offered to students. Following this decision, the VQA has undertaken a program of visits to providers (Praetz 2002); this program has shown that some schools have already introduced the VET as one more qualification and it started to be gradually accepted by the students.

Finally, one more recommendation, namely improving the educational outcomes and clearing pathways for work and learning for the school-leavers was followed. The VQA considered it necessary to not only ensure the school-leavers with opportunities for learning and work, but to strengthen literacy among low achievers who, as it has been proven, are the most likely to contribute into the high levels of unemployment in the county. Owing to the policies adopted, work became a part of the curriculum because, as it was acknowledged, extended work experience “yields a powerful effect of employability, independently of students remaining with the same employees” (Praetz 2002, p. 198). This ensured smoother transition of students into work and further learning. In this way, the Australian government has addressed the most important recommendations offered by Kirby in the Ministerial Review of Post-Compulsory Education and Training Pathways in Victoria.

Criticism of the Report

Though the changes introduced into the Australian system of education owing to the Kirby Report were extremely beneficial, there are still sectors within post-compulsory education and training that the report could have paid more attention to.

Firstly, the report neglected the importance of early intervention into the problem of early school-leaving. Kirby report contained several important recommendations on ensuring potential early school-leavers with proper guidance and support, but it failed to work out proper strategies of how high rates of early school-leavers could be prevented. Early school-leavers are often associated with their history of failure in school which has certain effect on their perception of post compulsory education. It is rather problematic to deal with this problem in post compulsory phase, which is why solutions have to be worked out already at the stage of compulsory education.

Above all, the schools should identify the groups of students who are at risk of early school leaving. According to Preventing student homelessness and early school leaving 1999, these groups primarily include students with special needs, such as indigenous Australians, students with physical and learning disabilities, low achievers, non-English speaking students, as well as students living in rural areas.

Special approaches to teaching these students need to be worked out, as well as restructuring of the curricula with regards to the needs and abilities of these students should take place. Besides, intervention programs should be implemented in schools; the aim of these programs should be to offer possible psychological help to students at risk, as well as discover what they expect from the system of education. This, as a way of dealing with the problem of early school-leaving, has not been offered in the report.

Moreover, early prevention should focus on the training of parental skills. This should be done within the frames of family involvement in education. The majority of early school-leavers come from the families with low SES (Kirby 2000), which suggests an idea that students’ parents might not be well-educated or, sometimes, even literate. This especially concerns non-English learners and their parents who may have a range of reasons for not to get involved into their child’s education.

These reasons may range from the parents’ feeling deprived or ashamed for not knowing the language of school, especially when facing the need to confront with their child’s educators, to differences in cultural traits between their own and the educator’s values and beliefs regarding education (Carrasquillo, Kucer and Abrams 2004). Parents should be in no way discouraged to take part in their child’s education. Thus, it is the responsibility of the schools to initiate the training of parental skills and to make parents more involved with their children’s education.

Finally, one of the most effective early intervention strategies is early childhood education. This should also begin with identification of those groups who are at risk of early school-leaving and focusing on the work with namely these groups. Participation in early childhood education has to be increased, but, what is even more important, sustained intervention should be ensured. Schools should provide long-term supports to their students through program continuity (Lamb n.d.) and take care about students at risk from their childhood education to the final phases of compulsory education. Therefore, these are the areas that the report could have addressed in emphasizing the importance of early intervention concerning the students who are at risk of early school-leaving.

Secondly, the report has not proposed clear strategies for increasing participation in education. One of such strategies could have concerned improved school culture. The matter is that school culture has a direct relation to retention rates.

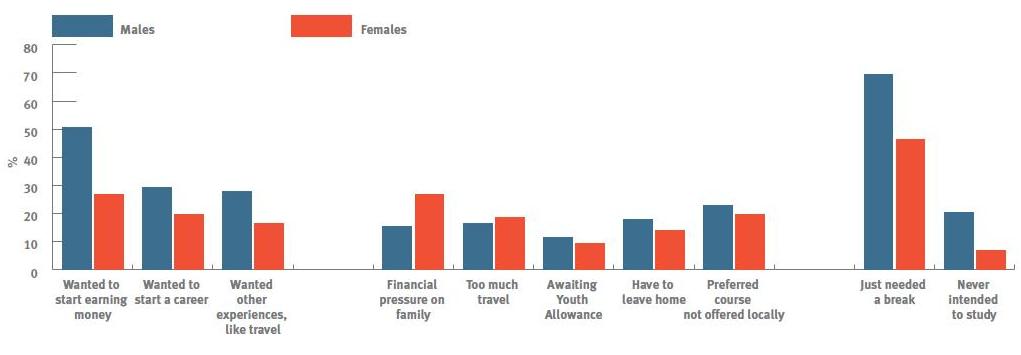

As mentioned by Wyn & White (1997, p.112) dissatisfaction with school culture is one of the major reasons of early school-leaving in Australia: “Early school-leaving is consistently associated with the ‘push’ of negative experience of school rather than with the ‘pull’ of a good job or a clear concept of how to establish a legitimate livelihood.” These negative experiences often result in students’ needing a break from school. According to The On Track Survey (2009), 29.3 per cent of early school-leavers belong namely to those who need a break from school. Figure 4 reveals the main reasons why the students leave schools early:

As the graph shows, the number of early leavers who need a break from studies prevails over those who have other reasons for leaving school early, which is related to unfavourable school climate. This is why paying due attention to school culture should be number one strategy for increasing retention rates.

Another important strategy that could have been outlined in the report is the implementation of student-focused programs instead of the school-wide reforms. Lamb (n.d.) posits that most of schools try to increase student completion through school-wide curricular and programs, whereas the interests of separate students are being ignored. These separate students are often students at-risk who, owing to different personal and social issues (low SES, ethnicity, health problems, etc) are forced to abandon education.

One of the most important activities with regards to this strategy is the implementation of programs oriented towards the reduction of social isolation of such students and strengthening the relations between them and the community; together with this, the schools can ensure the students with welfare and financial support, peer tutoring, pathway planning for the disadvantaged students, etc (Lamb n.d.). One more activity may involve the construction of curriculum in a way that would meet the needs of particular students (Caldwell and Spinks 2007). This strategy would result in students’ feeling their need for school and, consequently, increase the retention rates.

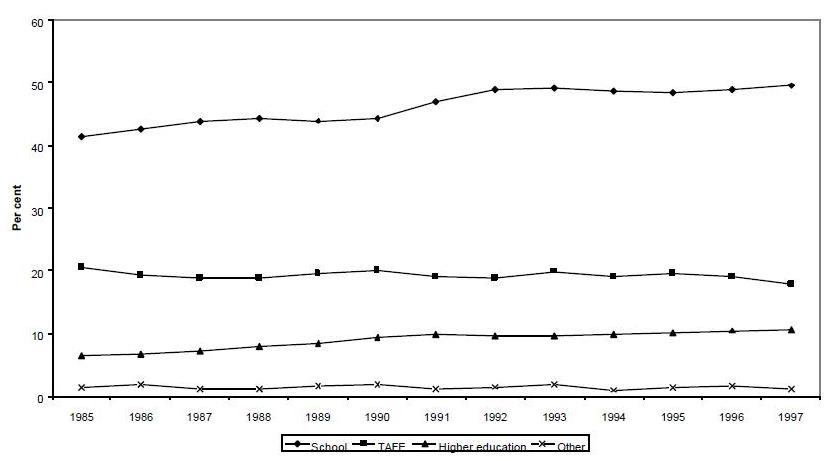

The report, however, has still proven to be beneficial for increasing participation rates. Thus, for instance, Figure 5 reveals that participation rates in higher education in Australia have been quite stable and rather low before the implementation of the Kirby Report:

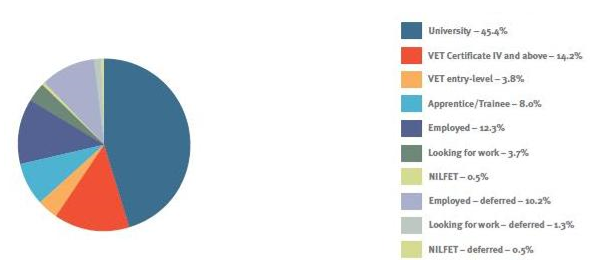

As it can bee seen from the figure, 10.7 per cent of population participated in higher education in Australia in 1997 (Education Participation Rates, Australia 1999), while after the Kirby Report implementation, there has been significant expansion in the Australians’ participation in post-secondary education and this number has risen to 45.4 per cent (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2009; The On Track Survey 2009). This can be seen from Figure 6 that reflects not only the participation of Australian students in university education, but their participation in other forms of post-secondary education:

It can be seen from Figure 6 that participation of students in higher education has increased significantly since 1997. Nevertheless, if the report outlined strategies for increasing participation more clearly, the results could have been better.

Thirdly, the report should have paid more attention to the VET and its benefits for the Australian education and its students. According to the report, VET in Australia has grown significantly and rapidly, but only 10 per cent of final-year students are involved into it (Kirby 2000). The report has discussed the necessity to use VET as a part of ‘preparatory cycle,’ as well as its use in combination with other certificates, the VCE in particular, but it did not emphasize and, consequently, address how VET could lead to better retention and school completion rates, as well as an increase in job opportunities for students.

Firstly, the report has underestimated the contribution of VET into student retention and increasing the rates of school completion. As stated by Montague (2006), VET strategies can be quite effective in coping with problems related to poor education and training participation rates in Australia. A NSW survey carried out in 2005 has shown that 60 per cent of students have chosen to stay at school only owing to their choosing a VET subject; among these, 70 per cent were low achievers (Stanley 2007). This is why VET options may be regarded as one of the main factors that influence the decision of potential early-leavers to stay at school.

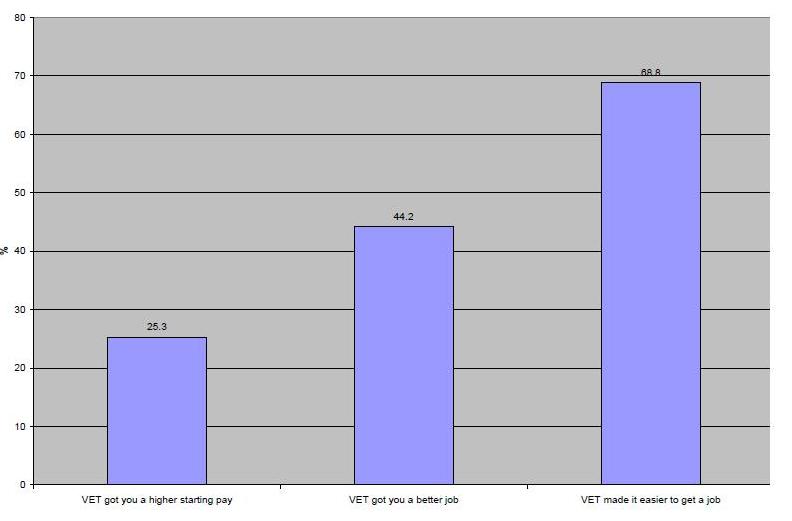

Secondly, the report has not considered the fact that VET leads to better job opportunities for young people. The main reason for young people valuing VET so much is that it ensures bridges between school and work thus making transition from learning to work smoother. In the course of VET, the students get an understanding of how their skills should be applied at work and what value they have for the employer. This results in around 90 per cent of VET participants being confident in their knowledge and skills after they complete the program with 16 per cent of them ensuring themselves with a work placement while at school (Polesel, Teese & Lamb 2005). As reflected in Figure 7, 68.8 per cent of VET participants have agreed that namely VET ensured them with smoother transition to the labour market:

It can be seen from the graph that the confidence in their future is crucial for some young people at school. This is why the meaning of VET for school completion and retention rates is indeed great. This makes VET a vital sector that the report under consideration did not account for.

Lastly, several other factors make VET appealing to young people and, thus, increase the retention rates and the number of those who complete school education. One of such factors is the adult climate in which VET is carried out which is significantly different from the climate of school education (Slade & Trent 2000).

Another factor is the practicability of skills that VET provides the students with. Unlike school experiences, VET learning is based on real-life examples, which not only makes the subject more understandable for students, but allows applying the acquired knowledge and skills in practice (Ryan 2002). And lastly, VET provides a variety of options for the disadvantaged young people, indigenous Australians and young people with disabilities in particular, which makes it attractive for the students. Thus, VET, like nothing else, can ensure high retention and school completion rates, which is why it should have been paid special attention to in the report.

Conclusion

Throughout the history of its existence, the Australian system of education has been trying to introduce changes into the ways the young people in the county are educated. Among several reforms that the government has implemented, there were no particularly effective ones. However, the Ministerial Review of Post Compulsory Education & Training Pathways implemented in 2000 proved to be quite beneficial for the Australian system of education.

This review has identified four major challenges to policy makers with regards to education improvement; these challenges included increasing the participation of young people in post-compulsory education, making this type of education accessible to disadvantaged students, avoiding educational outcomes that could threaten the country with economic instability (unemployment in particular), and ensuring lifelong learning that would make further education and employment possible for the population.

Addressing these challenges, the report has proposed several useful reforms the most important of which could be realized through the establishment of the Victorian Qualifications Authority (VQA) that, after it was established by the government in 2001, made the VCE more flexible and diversified it, as well as ensured the students’ access to other qualifications and made post-compulsory education accessible for the disadvantaged students.

At this, however, there remained education sectors that the review failed to address; these primarily concerned the importance of early intervention in early school-leaving, clear strategies for increasing school completion and participation in education, and the importance of the VET for increasing participation in post-compulsory education and training. It is through reviewing the existing recommendations and taking into account the newly proposed ones that the Australian government will be able to build an effective system of compulsory and post-compulsory education for its population.

References

‘Young Victorians on track for the future,’ (2007), Education Times, vol. 15, no. 10.

Australian National Training Authority, 2001. International practice and policy implications for Australia.[pdf] Victoria: NCVER. Web.

Caldwell, B. And Spinks, J.M. 2007, Raising the stakes: from improvement to transformation in the reform of schools, Routledge, New York.

Carrasquillo, S., Kucer, S.B. and Abrams, R. 2004, Beyond the beginnings: literacy interventions for upper elementary English language learners, Multilingual Matters, Clevedon.

Deka, U. 1998, Factors of academic achievement: a comparative study of high and low achievers, Northern Book Centre, New Delhi.

Education participation rates, Australia 1999. Web.

Kilpatrick, S., Abbott-Chapman, J. And Baynes, H. 2002, Youth participation in education: a review of trends, targets and influencing factors, Centre for Research and Learning in Regional Australia, University of Tasmania. Web.

Kirby, S 2000, Ministerial review of post compulsory education and training pathways in Victoria. Web.

Lamb, S. n.d. Effective strategies for improving school completion.” Web.

Malone, S.A. 2003, Learning about learning, CIPD Publishing, London.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2009, Education policy analysis 2001, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2000, From initial education to working life: making transitions work, OECD, Paris.

Perry, G. and World Bank 2006, Poverty reduction and growth: virtuous and vicious circles, World Bank Publications, Washington, DC.

Polesel, J., Teese, R., Lamb, S., Helmen, S., Nicholas, T. and Clarke, K. 2005, Destination and satisfaction of 2004 HSC VET students in New South Wales, Centre for Postcompulsory Education and Lifelong Learning, University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

Praetz, H., 2002, ‘Increasing equity through qualifications: the case of the Victorian Qualifications Authority,’ Australian Journal of Education, vol. 46, no. 2, pp.189-204.

Preventing student homelessness and early school leaving: putting into practice school and community collaboration 1999, Department of Families, Youth and Community Care, Queensland, Australia. Web.

Ryan, R. 2002, ‘Making VET in Schools work: a review of policy and practice in the implementation of vocational education and training in Australian schools,’ Journal of Educational Enquiry, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 1-16.

Slade, M. and Trent, F. 2000, Are they the same? A project to examine success among adolescent males in secondary and tertiary education, Paper presented to the Australian Association for Research in Education Conference, Sydney, New South Wales.

Stanley, G. 2007, ‘Education for work: the current dilemma of post-compulsory education,’ The Australian Educational Researcher, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 91-99.

The On Track Survey 2009. Web.

Volkoff, V. & Walstab, A. 2007, Setting the Scene: investigating learning outcomes with a view to the future, Centre for Post-compulsory Education and Lifelong Learning, University of Melbourne, Melbourne: Adult Community and Further Education (ACFE) Board Victoria. Web.

Wyn, J. And White, R. 1997, Rethinking youth, SAGE, London.