A common technique used in modern law enforcement is offender profiling. Driven by the use of investigative tools, evidence, and data, forensics can provide characteristics which can aid in the identification, apprehension, and conviction of an offender. While it is less common that a specific perpetrator is identified, criminal profiling can narrow down the pool of suspects by highlighting physical, social, behavioral, and other descriptions. Offender profiling is the backbone of modern forensics and crime solving, but it is an imperfect system and each of the distinct approaches has its practical limitations.

Common Profiling Approaches

The clinical profiling approach seeks to utilize clinical judgment, training, and experience along with clinical methods, particularly in cases where the offender is potentially experiencing mental health or psychological issues. The focus of this approach is to focus on the details of the specific cases and make individual clinical evaluations. The key principles of clinical profiling indicate that each advice to law enforcement should be:

- Custom made – not relying on generic material or anti-social stereotypes;

- Interactive – depend on the level of sophistication based on officer understanding of psychological concepts;

- Reflexive – advice should be dynamic, based on available evidence, with new information impacting not only future elements, but the construct as a whole (Cospon et al., 1997).

The clinical profile starts with visiting the crime scene and analyzing case material. It seeks to answer the three primary questions of what happened (in detail), how it happened, and to whom it happened. The profiler attempts to infer reconstruction of events based on evidence and infer motive based on relevant literature. It then leads to developing a psychological picture in the attempt to answer the primary questions. Demographical and social factors may be introduced as well for the depth of description. It is at this point the advice with markers of probability is introduced and discussed with the investigative officer. This approach is commonly criticized because it is relative subjective, relies on the practical experience and intuition of the clinician, and has biases such as potentially the need to please the officer by providing information which may contribute to the investigation (Vettor, 2011). One case of a clinical approach was described by Clarke and Carter (2000) when they identified descriptors of sexual murderer types with their work with sex offenders. For example, they found that there are sexually motivated, sexually triggered, grievance motivated, and neuropsychological dysfunction sexual murders.

Typological Profiling

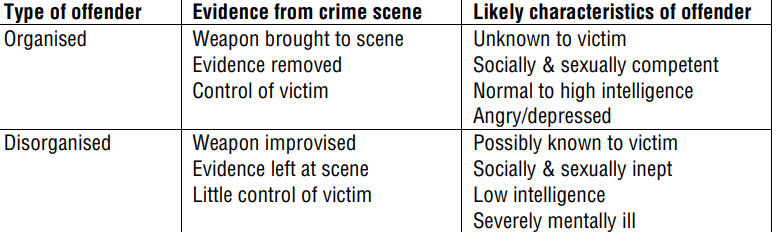

Typological profiling aims to investigate on behavioral evidence and clues obtained at crime scenes. This approach is based on the premise that different categories of offenders have differing psychological characteristics. Evidence on how the offender committed the crime is used to assign them to a typology. This approach is typically useful only in serial murders and rapes where several offences are connected in a series. It was developed by the FBI in the 1970s and follows a 4-step process. Data is collected from the scene and multiple sources; the crime scene is classified to determine if the offender is organized. As seen in the table below, different characteristics can be determined based on evidence. After, the investigators attempt to reconstruct the crime with all details. Eventually, the profile is generated based on physical, demographic, psychological characteristics, with all details included such as potential employment, age, sexual history, and others (Sammons, n.d.).

The typological approach was one of the first systematic approaches to offender profiling in law enforcement and has been tremendously influential. The benefit of this approach is that the typologies are key identifiers and can be used to facilitate predictions about timeframes and methods of future crime. It has been instrumental to codifying investigations to avoid perceptions that law enforcement is stereotyping or holds biases. The continuous research into typologies demonstrates that common stereotypes are usually wrong, such as an inadequate loner behaves like an average family man in social circumstances, being intelligent and employed (Palermo and Kocsis, 2005). However, the approach is criticized for being subjective and without relying on scientific evidence which on its own can be unethical. Furthermore, the crime scenes are often incomplete, and many assumptions have to be made, and if such evidence was to be used to make arrests and charges despite low reliability, it would compromise trust. There are suggestions that offenders can be both organized and disorganized, as well as that the sample on which this system was developed was too small, without any serious attempts since to determine the validity of these typologies.

Investigative Psychology Profiling

Investigative psychology is a technique which seeks to determine facts about an offender based on past crimes and behavior. However, unlike typology, investigative psychology profiling does not seek to categorize the offender, nor necessarily to diagnose their clinical dysfunctions as in the clinical approach. In investigative psychology, psychological theories are used to determine behavioral characteristics and potential patterns. In fact, Carter (2004) one of the primary promoters of this approach noted that creating truly valid and accurate classification schemes is difficult. It is a systematic methodology, emphasizing that psychology can benefit criminal investigations in various ways. Essentially, all aspects of psychology related to the investigation can be helpful.

While the approach does include research of offender groups, the created profile is a combination of similar studies examining similar casts. The approach is inductive and dependent on amount and accuracy of data collected. IP utilizes what is known as the five-factor model for the evaluation of the offender, which includes areas such criminal career, criminal characteristics, interpersonal coherence, time and space considerations, and offender’s forensic awareness (Petherick and Turvey, 2008). This approach takes elements from all the other approaches and attempts to create a holistic profile of the perpetrator based on the behavioral characteristics and choices in the context of the five factors.

Geographic Profiling

The geographic approach to offender profiling seeks to predict the offender’s approximate location, among which could be their residence, place of work, regular visitation locations, and others. The technique focuses on analyzing geographical elements such as the location of the crime, meeting place between criminal and offender, places where objects were abandoned, or body was disposed (in murder cases) and examining other influential factors such as familiarity with the location, potential barriers, and buffer zones. The premise to this approach suggests that crime locations are not chosen randomly. It is either a decision made through rational analysis of physical environments or subconscious reflections of the offender’s personality or personal life.

Geographic profiling is supported by a range of theories. First, based on environmental criminology, the principle of minimum effort indicates that given options, humans will choose the one that takes less effort, so criminals are more likely to commit a crime physically closer to their location, with the incidence of crime declining in likelihood the further away from ‘base’ an offender is. Furthermore, based on the familiarity principle, perpetrators tend to commit crimes in areas that they are familiar with and have a wide range of information such as potential hiding spots or escape routes, in addition to being more emotionally comforting (Lino et al., 2018). Geographical profiling has associated with location-oriented crimes, particularly at a serial level since the offenders typically operate within one geographical region or pattern in repeated crimes.

A well-known case was when geographic profiling was being developed, with one of its prominent contributors a Vancouver criminologist Kim Rossmo was contacted to aid with a serial rapist investigation. The area of the crimes covered a range of more than 7,000km2 among 3 major cities, with over 12,100 suspects. In one of the more recent cases, the offender took a credit card and used it for a range of daily life purchases in one of the cities. Rossmo conducted a geographic analysis overlapping the areas of the purchases and known crimes, narrowing the search to 2 districts significantly lowering the area and investigation focus. After hundreds of hours of manual fingerprint matching due to incomplete evidence, the perpetrator was found, with DNA matching. The offender was narrowed down to the area as it was the residence of his mother, whom he visited regularly. The geographic prioritization allowed to narrow the search area to top 3% of the geoprofile, but without this technique, it would have been only a 50% possibility (Medeiros, 2014).

Most Effective

Considering and comparing all of the above approaches, it can be argued that the geographic approach is the most effective, but likely not all cases will have enough data to make an accurate analysis. The effectiveness of geographic profiling is measured through a concept known as hit score, which is the percentage of the total area covered by crime sites in an area where the analysis identifies as the ‘home base’ of the offender. A random hit score would be 50% but most average hit scores of investigations are under 5 percent, greatly narrowing down the area of search and sharpening the geographic focus of an ongoing investigation by 10x (Laverty and Maclaren, 2002).

As technology progresses, along with many more data points available due to the digitization of the modern world, this approach becomes increasingly more accurate. While psychosocial analyses and typologies used in other approaches are potentially helpful, they are subjective and theoretical. The geographical approach takes into account characteristics of the perpetrator. However, it is more effective, because law enforcement usually does not hold databases of psychological characteristics, which can differ based on evaluating expert as well. Law enforcement holds empirical data such as addresses of people and relatives, past arrests, fingerprint and DNA data, and financial information. Therefore, to present a smaller area with some potentially defining characteristics of the offender is much more likely to find a match in comparison to determining a typology or clinical diagnosis with mostly hypothesized attempt to predict behavior. Furthermore, approach is the most ethically competent as it relies on calculations and empiricism rather than personal profiling, significantly limiting the number of biases and misconceptions that can be implemented in this approach.

Court of Law

Beginning of the 1990s, offender profiling began to be presented in some cases as forensic evidence. Both prosecutors and defendants have called criminologists, special agents, and psychiatrists as ‘expert’ witnesses. The three types of offender profiling evidence which has been considered are motivational analysis, linkage analysis (connecting more than one crime committed by the same individual), and modus operandi evidence. For decades, the general standard for expert testimony was evaluated under Frye v. United States which gave the judge an opportunity to evaluate whether the techniques described represent scientific or technical consensus. However, in a trilogy of Supreme Court known as Daubert trio the Federal Rule of Evidence 702 was established (George, 2019). The new rule establishes standards such as that the expert’s specialized knowledge will help the trier to understand the evidence, the testimony is based on sufficient facts and data, reliable principles and methods are used, and they are applied correctly to the case (Legal Information Institute, n.d.).

After the Daubert rulings, the requirements of admissibility are now based on reliability, peer review, error rate, acceptance and standard, and proper fit to the case. Therefore, given the current standards, offender profiling technique and methodology must be based on scientific evidence, reliability, and relevance. Offender profiling, despite all of its attempts to attest to scientific principles, remains not fully reliable and subjective in many ways. There are no standardized methods in the forensic application which can be constituted as scientific evidence (Bosco, Zappalà and Santtila, 2010).

Out of the four approaches investigated, the geographical approach is once again the most fitting of the standards of admissibility. It relies not only on psychological theories guiding offender behavior, but seeks to support this with data. The concept uses largely empirical data such as coordinates, distances, geo-pinged locations (from smartphones), financial data, dates, and others. Using the geographical approach, complex empirical analyses are conducted based on the data to generate probabilities of potential locations (Lino et al., 2018). If presented competently, it will meet the necessary level of scrutiny under rule 702 for court admission unlike other approaches which rely strongly on theory and hypotheses formed from incomplete investigations of crime scenes.

Reference List

Barreda, D.S. (2020) ‘The application of Newton and Swoope’s geographical profile to serial killers’, Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, pp.1-11.

Bosco, D., Zappalà, A. and Santtila, P. (2010). ‘The admissibility of offender profiling in courtroom: A review of legal issues and court opinions’, International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 33(3), pp.184–191.

Canter, D. (2004) ‘Offender profiling and investigative psychology’, Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 1(1), pp.1–15.

Clarke, J., & Carter, A. J. (2000). Relapse prevention with sexual murderers. In D.R. Laws, S. M. Hudson & T. Ward (Eds.), Remaking relapse prevention with sex offenders (pp.389-401). London: Sage.

Copson, G., Badcock, R., Boon, J., & Britton, P. (1997). ‘Editorial: Articulating a systematic approach to clinical crime profiling’, Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 7, 13-17.

George, J.A. (2019). ‘Offender profiling and expert testimony: scientifically valid or glorified results?’, Vanderbilt Law Review, 61(1), pp.221–260.

Laverty, I. and MacLaren, P. (2002). ‘Geographic profiling: a new tool for crime analysts’, Crime Mapping News, 4(3), pp.5–8.

Legal Information Institute. (n.d.) Rule 702. Testimony by Expert Witnesses. Web.

Lino, D., Calado, B., Belchior, D., Cruz, M. and Lobato, A. (2018) ‘Geographical offender profiling: Dragnet’s applicability on a Brazilian sample’, Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 15(2), pp.149–161.

Medeiros, J. (2014) ‘How geographic profiling helps find serial criminals’, Wired. Web.

Palermo, G.B. and Kocsis, R.N. (2005) Offender profiling: an introduction to the sociopsychological analysis of violent crime. Springfield: Charles C Thomas Publisher.

Petherick, W.A. and Turvey, B.E. (2008) Nomothetic methods of criminal profiling. Edited by B.E. Turvey. Cambridge: Elsevier Academic Press.

Sammons, A. (2013) Typological offender profiling. Web.

Vettor, S.L. (2007) Offender profiling: A review and critique of the approaches and major assumptions. PhD Thesis. University of Birmingham. Web.