Introduction

The oil crisis in 1998 and 1999 and the related financial problems encountered by the GCC states motivated the authorities to institute reform strategies to control deficits. These programs were implemented at different levels in accordance with specific platforms in every state of the GCC. But in all the states, there were increased consolidations which improved their conditions and reduced respective budgets’ weaknesses to pressures by trade shocks or oil price’s sudden fall. Some GCC states made improvements by segregating public expenditure from immediate financial concerns to programmes in oil revenues and creating savings and stabilization measures. Public expenditure programmes were difficult to execute, such as reducing employment and range of budgetary subsidies to local governments. Welfare systems had to be limited.

The reforms in the financial sector by the different GCC states as a result of the 1998-1999 oil crises were made in line with respective government platforms. For example, Bahrain formulated the Islamic government bills to correspond with the function of the Islamic monetary programmes; provided measures in improving discreet banking regulations; reformed anti-money laundering laws in 2001 in accordance with FATF guidelines; and enforced the Stock Exchange laws.

Kuwait also made reforms by adopting the foreign investment legislation granting aliens the right to own and conduct trading with companies registered with the Kuwait Stock Exchange, but with some guidelines. Kuwait has focused on population growth since it has low level of population which accounts for a lower labor force growth. The concern with its labor force growth motivated Kuwait to pour some budgeting on this problem to increase the percentage of Kuwaiti nationals infused into the labor force. By 1993, this constituted 20.4% of the entire labor force. By increasing, it also meant to add spending for manpower development and training. Kuwaiti authorities were determined to increase the quality of its labor force through education and training. Male and female employees enhanced their knowledge through distance education and lifelong learning.

Government also focused on reducing infant mortality which was then reduced to about 15 per 1,000 babies born in 1989. This continued until the liberation of Kuwait. The government was determined to support population growth by increasing child allowance to KD 50, or US $170. Other allowances for education, health, and housing for children were also increased.

The Oman government made reforms in the banking sector and enhanced laws on securities by expanding the power of the Muscat Securities Market. It also reformed banking laws and reduced borrowing. Saudi Arabia allowed foreigners to conduct business in the stocks exchange and formulated laws on capital markets. It also followed the guidelines set by the FATF by providing stiffer measures against money laundering.

During the early years of the United Arab Emirates, President Shaykh Zayid made every move to build a strong federation. He visited places in the UAE to supervise every project in the remote areas of the country, to see their progress, and to converse or personally communicate with the population and the so-called grassroots. During these modern times, the United Arab Emirates has become financially active by establishing the stock markets with a corresponding regulatory body. Along with this, the UAE activated a Securities Law to lower down volatility and violations in the security markets. The government had to ensure that money laundering was not a problem as it strengthened laws on laundering in line with FATF guidelines. The central bank provided measures to reduce risks.

On the other hand, Qatar spent more for services for its people from the revenues provided by the natural gas. Qatar got rid of interest limits on deposits; improved bank management and limite nonperforming assets; and provided new programs to improve liquidity supervision. Transactions between commercial banks and the central bank were simplified and made easy.

Recent policy initiatives were more focused on upgrading educational institutions and systems to pave the way for more high-tech, high-skilled industries. So-called first generation policy initiatives have been refined and made systematic, like in the countries of Qatar and Abu Dhabi. Education can provide more quality employment for nationals and diversification can also pave the way for high-salaried employment. The problem is with the young nationals who have not opted to work with the private sector. Young nationals have been pampered by the government policy of providing special privileges and high salaries if they are employed in public institutions.

Across the GCC states, education is the main thrust, with the big part of the national budget across different states allocated for education and training. Saudi Arabia’s budget for education in 2010 amounted to $36.7 billion; for the UAE education had a bite of $2.7 billion (equivalent to 22.5 percent of the national budget); and Qatar gave 20.5 percent for education. It was emphasized that the primary aim of the education budget was content of the curriculum.

Qatar introduced a program known as “Education City,” attracting six popular U.S. universities to provide satellite campuses in Doha. The Qatar government was successful on this by meeting the requirements and shouldering the operational costs of the satellite campuses for 10 years. On the other hand, the UAE convinced the Sorbonne and New York University to set up satellite campuses in Abu Dhabi by answering the costs for their popular institutions. In Saudi Arabia, King Abdullah donated $10 billion from his personal funds for the establishment of the graduate-level King Abdullah University of Science & Technology (KAUST). Expenses in establishing the university reached $2.6 billion. Nevertheless, young nationals are not too attracted to these new universities.

All of these programs seemed to be successful for the GCC states, but, as many commentators would say, the GCC has still a long way to go. Whether it is on the right track remains to be seen. Development is seen in many areas, but the smaller states are lagging behind. Wealthier states should help by using oil revenues to provide sustainable development to these states.

Objectives

The objective of this dissertation is to examine and investigate GCC public expenditures after its establishment in May 1981. The six GCC countries are composed of one economic giant, Saudi Arabia, and the rest are smaller ones. The UAE consists of a federation of smaller states in the Gulf.

Another objective is to find out how public economics and public finance have worked out in this region amid the turmoil and the ravages of war in the Middle East. This region is one of the most troubled places in the world, the reason why smaller states have to find ways to be secured and safe, while some depend on global powers for security and economic independence.

In discussing the subject on public economics and finance, some other factors and discipline may emerge and find their way in the discussion. For example, the GCC’s roots and formation and their subsequent projects and plans for the future were provided in the literature. One subject led to another. This is because the subject of public expenditures, including public economics and finance, are broad. Nevertheless, this Researcher focused on the GCC and the facts and circumstances surrounding the subject of public expenditures.

Methodology

The methodology provided in this paper is review of the literature. The literature was sourced from journals and articles found in physical and on-line library or digital repository. The journals and articles are peer-reviewed; they provided a great source for an interesting discussion on the subject of public economics and finance in the GCC.

Literature review as a methodology provided an analytical study of the information and data found in the literature. The main purpose was to help readers in understanding what was being researched, making known to the readers the strengths and loopholes of studies conducted in that subject.

This Researcher could not have another way of research other than the chosen methodology since it is impossible to be physically present in the geographical areas mentioned in this study. The articles and past researches by authors and commentators provided a comprehensive background for the subject matter. The job of this Researcher was to research from the databases and books about public finance and economics and the public expenditures made by the GCC countries.

Literature search was a challenging job. I had to find words from my creative imagination to feed and draw from search engines articles and journals for this study. It was an enormous job because the subject on GCC and public finance and public economies are broad. It took me days to find a specific topic and inputted the words in the databases. Right search words were used to find the appropriate articles and journals from the databases.

The databases used were Academic Search Complete and Academic Search Premier of the EBSCOHost where a vast amount of scholarly journals, ebooks, and articles could be found. This multitude of journals were retrieved through a paid account and organized in the literature review which became a research methodology.

Articles included in the study were about the strategies used by the member states of the GCC. These articles were rich with information about the GCC and public expenditures, public finance and policies instituted by the GCC authorities in the course of recovering from the turmoil of war, in seeking economic independence and security, in diversifying and freeing themselves from dependence on oil.

After the gathering of information, the next move was to analyze the literature and provide a critical analysis of the literature. But first, there was an activity known as critical thinking – to motivate my inner desire in skilful research and prepare myself for the systematic analysis. Literature review was not applied as a narrative way of telling the stories; the job required a critical analysis.

Literature Review

Background

In the period before the formation of the GCC, there were joint efforts for trade and security issues among the Gulf countries. This was a period characterized of separate initiatives by two or several countries making moves. For example, a move by the Kuwaiti authorities initiated the formation of the General Board of the South and Arab Gulf which provided for several benefits in the form of cultural, scientific, and health-related services to Arab Gulf states. The United Arab Shipping Company was also established for countries like the UAE, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Qatar, and Kuwait as members. The Gulf Ports Union was also formed for Gulf countries. The Gulf Petrochemical Industries Company was a corporation of firms coming from Bahrain, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Other activities that led to the establishment of the GCC included shipbuilding companies, petroleum corporations, shipbuilding and dry dock ports, and petroleum related businesses. Large amounts of money were poured in by the Gulf States to make their efforts work and for the job of providing security and economic cooperation. Other reasons why the GCC was formed were the unique relation existing between these countries, the similar political orientation grounded on Islamic principles, a common destiny and common goals.

The Gulf Cooperation Council is a regional grouping of six member states in the Gulf Region with a common objective – to counter security threats posed by communism, pan-Arab Nasserists, the PLO, and other dictatorial powers of the Gulf countries. In 1967, leftist groups were expanding their territories and powers over the smaller Gulf States. During this period up to 1975, forces from dictatorial regimes were aligning their powers. Aden became communist-ruled and renamed People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, which supported a group known as the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arab Gulf (PFLOAG). This group also endorsed a rebellion in Oman’s southern province known as Dhofar. But this was later dealt with by a formidable force of British, Jordanian and Iran’s military under the then Shah of Iran. PFLOAG was also supporting another liberation front in Bahrain. Because of the efforts of the GCC governments, stability in the Gulf and availability of oil for western countries are ensured. In short, the GCC was formed amid a very tense political positioning by big countries and superpowers during Iran’s Islamic Revolution followed by the unsettled war between Iran and Iraq.

The primary aim in the formation of the GCC was for defence, but the initial motive was to preserve the monarchies. This was followed by a military cooperation with western countries, then, it was triggered by the Iranian revolution and the Iran-Iraq war. But whether it was for security reasons, other reasons for the founding of the GCC evolved, such as economic in nature. GCC states are now aligning their strategies for economic development. They have big plans – to support themselves, the smaller states, and to become big as an alliance. Their most ambitious project is the creation of a monetary union, to anchor on the European Union.

The GCC first encountered security threats before and during its formation, but there were other threats, such as economic threats, or the lack of sustainable development for members in the countryside. These threats allowed them to wish for economic integration. Although there many factors to be considered in economic integration, the GCC did not have much difficulty in integrating their respective economies, unlike the integration of political and military areas which really takes time and a lot of efforts. Economic integration was sensed as the economic “secret” motives of these smaller states who had hoped to emerge victorious in the fight against giants and troublemakers of the Middle East.

The quest for economic integration stemmed from their desire to secure (and improve) a common product – oil and gas. The GCC has the biggest oil and gas reserves. GCC member states are active members of the OPEC.

There were issues that had to be resolved right away. Economic competition among the states had to be dealt with, and they had to make their efforts work well. For example, there was the issue of pricing arrangements on their oil-related products, including diversified products of chemicals and metals. The skills and educational levels had also to be addressed promptly since they were not delivering quality work. These issues were resolved because of the members’ common desire to improve and work for the country. However, the GCC states had countless problems that had to be resolved as individual states and as a collective nation.

In the 1980s, the GCC shifted focus to becoming a monetary union and to issue a single currency, to imitate the example of the European Union, despite political problems existing in the Middle East and North Africa. Experts backed the move considering that five of the GCC states, i.e. excluding Bahrain, have an abundance of oil and gas for exports, the same structures and similar cultural affinities and peculiarities. (The subject on monetary union and a single currency for the GCC is discussed on Section 2.6.3 and in the proceeding sections.)

Public Finance

The big idea behind public finance is that it is financial management for the expenditures of a country. This concept and principle is demonstrated on an example of a family, which is run by the head of the family, with money sourced from the household income in the form of wages or business earned by members of the household. The head of the family has to balance the budget and take all necessary measures that the money is distributed fairly and equally among the members of the household.

In a larger family, we have the government that supervises and administers welfare and justice, and all the other services needed for the general public, including industries and businesses (the family). The government maintains all the other functions like the armed forces, the police, social security, welfare for the elderly, the poor and marginalized, and many other services. Without money, the government cannot function and serve the people. This is the job of public finance.

Public finance encompasses government services and payments made or to be made for services for the government, including welfare fees, and other functions by which government spending can be covered through ways and methods that the government can acquire funds, like taxation, aids and borrowing from other countries or institutions.

Public finance involves money and how this can be allocated and distributed to the different departments and welfare institutions. The government can find ways, or money to support the many services, through taxation and customs duties of businesses and enterprises. The many services given to citizens’ families and businesses affect economic activity and revenues can be divided.

Public finance also involves lending and borrowing, but governments should be banned from acting like banks or private organizations that lend and borrow, and when they borrow, they do it on a large scale. They do this purportedly to build public infrastructure, bridges, schools, hospitals, and for public service and welfare. In the process, they collect taxes and tariffs so high the people cannot pay.

Public finance is for the good of the public. It has to be used for welfare purposes. Public finance therefore is not for evil intent, and has always been devised to deliver services where they are needed.

Public Economics

This dissertation is concerned with the subject of public economics, with reference to the GCC states and their implementation of public expenditures. Public economics is the link between the state and the market; it concerns government or public policies on the economy, emphasizing on taxation. But this is not just about taxation because it encompasses areas pertaining to market failure as influenced by external forces and policies pertaining to social security. The beginning emphasis is on the collection and government spending of revenues collected from various government agencies and programmes with the different aspects of intervention. Public economics also concerns public debt and incidence of taxation as it is related with social decisions. Many authors explained that public economics mostly referred to policy and how it is applied for public consumption.

The discussion on public economics can be distributed down to different specific subjects, but the most interesting and productive type should focus on how alternative policies affect the general public and the government and what is the optimal policy. In this case, there should be a distinction between positive economics and how it is affected by the introduction of a new policy. The theory should focus on how economic agents plan their activities and how these activities are executed in line with the new policy. Policy makers must weigh down the pros and cons of the optimal policy and how each policy performs and which is on the weighted balance of the equilibrium.

Public economics has been affected by neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is the ‘radical reconfiguration of the relationship between the state and the market.’ Public economics has become sophisticated because of the recent turn of events in history, such as the U.S.’s role as world leader in the Second World War, the need to rebuild the infrastructures damaged by the war, and the need to deal with welfare economics and the welfare state. With respect to the GCC, public economics refers to security and the need to focus on development of smaller states that have been lagging behind.

The theory on public economics states that the government should be able to help in maintaining the prices of commodities and products in industries so that a framework could be built for a democratic society to improve and develop. Moreover, the success of the neoliberal project depends on the use of the state as a tool in the marketization policies; examples of these are ‘privatization, financial liberalization, trade liberalization, deregulation, rolling back of the welfare state’.

Public Expenditures of the GCC States

In the 1970s and 1980s, the GCC countries were concerned with building domestic infrastructure and were not thinking of diversifying away from oil. To discourage dissent and political activities, citizens were given social benefits and there was no direct taxation. The welfare system was one of the most comprehensive and generous, and was fully appreciated by its citizens. GCC governments provided free education, looked after the health of its citizens, provided housing assistance and many household necessities including utilities and gasoline. Citizens were also provided jobs in the public sector, whose salaries were very much higher than the salaries in the private sector. After 20 years of service, GCC citizens can retire with 80 percent of their last salary. Governments had surplus money to provide jobs in order to make it appear that there was no unemployment.

In public economics, authorities study how to make use of meager resources to finance the various functions of government. The resources are in the form of taxes and other duties and income from businesses of the government. The GCC countries have made measures to use these meager resources, although oil was the main source to provide for government expenditures. Bahrain liberalized the telecom sector and invested much on mobile technologies and the telecom industry. Other states, like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, haven’t made moves of liberalizing their respective economies. There is much competition in this sector of the telecom market however, with the entrance of foreign firms involved in mobile technologies. Telecom competitors were also penetrating economies of UAE and Qatar in 2006.

The GCC benefited from high oil prices and economic activity made by investors. In 2008, the GCC produced one of the highest in its history of oil production, soaring up to 16.4 million barrels a day, amounting to an increase of about 7 percent compared to the previous year. This influenced consumption, increasing from 84 million barrels per day during 2005 to 86.9 million daily.

In 2004 and 2005, economic stability was seen in Jeddah, Riyadh and Qatar, with industries and offices outperforming the residential sector in terms of output across the six countries. The GCC provided more opportunities in terms of business and trading. More expenditure was being poured in the financial sector as corporations grabbed the opportunities of low interest rates in borrowings. Private investors had had increased investments, particularly in Islamic and conventional funds. In 2006, GCC economies were rising amid high oil prices. Governments of these states were reporting surpluses and increased economic growth. Governments were pump priming through infrastructures and more investments, allowing more jobs and requiring more foreign workers.

For the period from 2005 to 2030, large amounts of investments are expected in the oil industry. In the Middle East, around $500bn is expected for activities in exploration, development, and other oil businesses. Governments of the GCC states are also expecting private sector participation in the energy industry. But experts realize that dependence on oil cannot go on forever. Petrochemical giants are expected to enter the scene as governments start to divest their stakes in the energy sector.

Diversification efforts in the GCC economies have been focused on the non-oil sector. The authorities took advantage of the export revenues generated by the oil sector and poured it on the non-oil sector. There is now the linkage between the two sectors, the oil and the non-oil sectors. In the United Arab Emirates, there is an imbalance in wealth creation among the member states. But the federal administration has used Abu Dhabi’s money to help the smaller members. Dubai is prosperous and leading in several businesses, such as real estate, tourism, bank and finance, and is also a commercial hub as big multinational corporations hold their headquarters there. Dubai is leading in diversifying to the non-oil sector.

Sharjah, one of the emirates, has used small-scale industries in bolstering its economy and in serving Dubai and the rest of the UAE. There are educational institutions now proliferating in Sharjah, attracting students from the Gulf and the rest of the Arab nations. Fujairah, on the other hand, leads in maritime services and its international airport and container port terminal. Abu Dhabi is also diversifying into non-oil but its capital came from oil exports. The private sector is focusing on this capital for the booming economy.

The GCC states, through shared efforts, have built their own business out of oil. First, they have an oil refinery situated in Oman. This is one of the profit generating ventures that can provide source for the GCC to venture in other products, or for diversification. Refined products can meet other financial requirements for the GCC, for example petrochemical products which can be sold in higher prices. The GCC has other big plans for refineries; some of these have already been set up in Bahrain, Kuwait and in Saudi Arabia. These are necessary steps for the GCC’s diversification strategies and shifting to non-fuel products. Another big move was the building of a long oil pipeline, approximately 1,700 kilometers, that would connect Oman to other states, crisscrossing the Strait of Hormuz. The pipeline was connected from a terminal to other points in Oman.

Development of the Labor Force

Skilled manpower has always been a problem of the GCC countries. Migrant workers, who mostly come from Asia, dominate the workforce. With this situation, the private sector is largely dependent on foreign labor but this also put responsibility on the public sector to absorb the workforce. Thus, the thrust of the GCC countries – and their future plans – is to involve more the national workforce and by 2020, at least 75 percent is expected to be already involved in technical and professional jobs. GCC countries have to invest much on improvement of skills and competitiveness of the national workforce. Labor or human capital has to be improved, with emphasis on education. This is another area where the GCC states will focus their expenditures.

In the early years of the GCC, analysts predicted of the coming in of labor force from various Asian countries and the GCC’s continued dependence on foreign labor. The most important reason for this labor influx and GCC’s dependence on migrant workers was that the small and young population of the member states did not want to work in the private sector. They were used to special privileges given them by the government, such as higher wages and early retirement.

There was also the need to maintain the existing “old” infrastructures that had been there since the seventies, and the tendency to “secretly” hire foreign workers because of the stringent measures imposed by government regulations. All these affected the volume of migrant workers entering the GCC.

The growth and development of existing national labor force influences the demand for jobs in the GCC. There were changes in the GCC’s indigenous labor force, but mostly they were young and had little knowledge about the jobs offered in the oil industry. Thus, the governments had to depend on migrant workers.

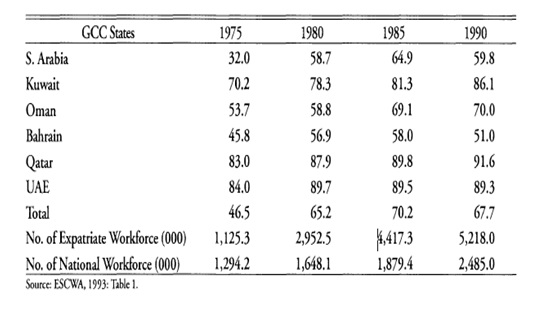

Table 1 above shows the percentage of expatriate work force in relation to the total work force of the GCC countries for the period 1975-1990.

The significance of labor or human capital to economic success of a country has been the subject of several empirical studies. There is the link between human capital and economic development. The theory states that a country can have higher economic growth if it invests in education. Human capital can trigger economies of scale with output exceeding inputs. Another way in which human capital boosts economic growth is when educated workers influence others around them. Economic growth is also obtained through research and development and human capital’s introduction of innovation and changes in products.

The GCC countries have a large population of migrant workers: in Oman, it is 33% while in the UAE, it is 90% of the entire labor force. Migrant workers are recruited by the private sector, working as professionals and as ordinary laborers. There is a discrepancy in the employment of nationals and expatriates; for example between 2000 and 2010, there were only 2 million GCC nationals for 7 million available jobs, which meant that the 5 million were expatriates.

Privatization in the GCC

After the oil shock in the early seventies, new opportunities loomed in the horizon for the GCC states. Public spending was exacerbated by the private sector, with many of the firms coming from petrochemical and fertilizer sectors building manufacturing plants in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and in many other parts in the Gulf region, particularly the GCC. In Bahrain and Dubai, the private sector built cement factories and ship repair yards.

GCC is moving towards privatization in order to acquire funds to support the governments’ public expenditures and to ease government load of managing enterprises. There is also the concern of lack of equal chances for the people. For example, there are revenues reserved for the royal families while a great portion of the population goes hungry. Privatization may lessen the present preferences of the royal families, but there is also the negative side on this as separating the private sector and the royal families may result into a political backlash. The unrest in the Middle East was due to lack of economic opportunities although they seemed political in nature, at first glance.

Privatization across the GCC is gaining ground. This includes privatization of public enterprises, like telecommunications, public necessities like water and energy needs, banking and finance. Bahrain is spearheading privatization through the formulation of a government council known as the Supreme Privatization Council. Abu Dhabi is also making its move of privatizing. Muscat’s Securities Exchange has provided a different method known as the “golden share,” making available some shares of state-owned entities for public investing.

Privatization was conceived by the GCC authorities with the following objectives:

- The general objective is to provide a wider playing field for both public and private entities within the GCC, collect more revenues to support government expenditures in building infrastructures, and motivate competitiveness in the private sector.

- The specific objective states that privatization enhances “industrial investment culture” to encourage citizens to invest in new businesses and motivating them to participate in economic activities.

- To provide the government the chance to work on other developmental projects and ease the burden of managing businesses which is a job of the private sector.

The main thrust of privatization is to free the government from running industrial institutions. These public firms had been provided privileges, or preferences in the form of government subsidies, which their private counterparts didn’t enjoy. The GCC privatization team provided measures to avoid monopoly, such as when a private firm would acquire majority shares in one industrial enterprise. This happens if the public institutions that would have been privatized are majority owned by private companies.

Organizational culture of soon-to-be privatized firms will have to be maintained through careful planning and consultation. The privatization plan will have to clearly show that share prices are not so high or not too low. Citizens are enjoined to participate, invest and acquire shares, but the maximum share available is limited at one percent.

There is a need for information dissemination about efforts of industrialization in Saudi Arabia, the other GCC countries and other details about the industrial enterprises working there. These measures are important in convincing new shareholders to invest in the privatization projects of the government so that they can be a part of the new investor community and can be a moving force for efficient management and performance. The government has to divest itself of the shares in order to collect more funds for another round of new investment for its people.

Shareholders of Privatized Entities

As stated, shares of stocks of public enterprises to be privatized are to be opened for all citizens who have the capacity to buy and become shareholders of a new private firm. The standing policy is to allow Gulf citizens to acquire and trade shares in the registered companies in the stock exchange. Non-citizens are allowed by law to own a maximum of 49% but they are second priority. Other Gulf governments and regulators of stock exchanges in the GCC countries have indicated that they are reviewing these policies in order to allow foreign investors to enter the scene and purchase shares in the privatized entities. The newly-formed Unified Economic Agreement of the GCC provided for privileges of ownership among citizens of member states. There have been moves for the establishment of a stock-exchange that would have jurisdiction over the entire GCC. Other stock markets within the GCC have regulations providing free access to GCC citizens, or to members who are: citizens in the GCC; organizations and entities owned by these citizens and the joint ventures and companies they have formed; foreign-owned corporations that have registered in the GCC; and foreign individuals and organizations who wish to invest in the Gulf.

The stakeholders include the institutions running the GCC and other agencies and individuals involved in the stock exchange. This includes the different ministries or departments of the governments, for example the ministries of Economy and Commerce, and all the other agencies in charge with money management.

Economic Objectives

It is a fact that one of the reasons for establishing the GCC was for regional security. Later, its ultimate aim was to form a monetary union. The introduction of a single currency became one of its economic objectives. This regional grouping, along with the activities it has created, has attracted the world’s increasing attention. As mentioned, the GCC is situated in a politically unstable area of the globe but it has oil reserves large enough to make it an economic might and to gain global attention.

The GCC’s economic objective is to coordinate and align the economic policies of member states by creating a common market like that of the European Union. This led to the creation of businesses and industries and other efforts for economic development in a cooperative effort among the member states. Economic cooperation was further enhanced with the 1981 agreement calling and granting privileges for citizens of their countries, like freedom of movement, commerce, and creation of an economic infrastructure. The agreement eliminated customs duties between the countries and coordination of import and export rules and regulations, among others.

The economic performance of the GCC during the economic meltdown in 2008 is worth emulating for the rest of the Arab countries and the world. The continued economic growth was caused by two factors: the continuous rise of oil prices and the increasing FDI from large multinationals willing to invest on oil and other industries in the GCC. This made Joseph Ackerman, chairman of Deutsche Bank Group, to comment that the rise of infrastructure projects in the GCC slowed down the effects of the economic meltdown in the United States.

Fiscal positioning

The GCC created a step-by-step reform strategy to focus on a broad spectrum of structural reform that would realign resources in accordance with market forces. The strategy was aimed at solidifying fiscal position to ensure fast economic growth. GCC fiscal positioning has the following characteristics.

- Fiscal realigning and focusing on budget structure to provide long-lasting fiscal strength in accordance with multifaceted economic goals, protect the economy against trade problems and improve private sector relations. GCC reduced government subsidies, improved tax collections and adopted a systematic tax collection system. The fiscal policy was formulated over a medium-term strategy with the assumption of a traditional oil price in order to reduce the dependence of expenditure on short-term oil income and gain more savings to counter possible external shocks.

- Strengthening the private sector through legal means and government reforms and privatizing existing government corporations. This would include liberalizing the institutions and minimizing controls on the private sector or businesses, encouraging property rights to provide for a healthy and strengthened market system where investors compete; the government should properly define the framework in passing on the state enterprises to the private sector in order to attain market confidence.

- Liberalization of investments coming from foreign corporations in order to acquire more money from foreign investors and acquire new technologies to support new thrusts of economic development. This liberalization will eliminate discriminatory policies pertaining to capital inflows as they invest in the domestic market; provide a wider playing field for both foreign and domestic investors and narrow down the tax treatment on these two types of investors; properly develop the capital markets within the member countries of the GCC.

- Reforms within the workforce. Expenditures will focus on providing jobs for the national workers, including those affected by the privatization efforts of the governments within the GCC.

- Closer cooperation and consolidation of the different economies. This strategy worked on facilitating a collective policy agenda for the member countries. This will further enhance market competitiveness and attract more investors.

An Agreement by the GCC

The GCC formulated the United Economic Agreement which envisions synchronization of fiscal policies of the different states. This treaty is similar to the treaty by the EU known as the European Commission Treaty which envisioned full cooperation among its members. The UEA asked for limits on budget deficits and also limited public debt. This regional treaty of the GCC affected fiscal functioning and the activities of government agencies responsible for public expenditures. In the GCC, coordination should be afforded by the members during budget planning so that public expenditures can be determined beforehand.

The GCC needs coordination among the member states. Coordination motivates decisions that enhance the general welfare of all the members, and refers to shared goals and duties to carry on with the agreed policies. Coordination provides for a clear understanding about the mission, a logical and well-conceived set of principles, a set of policy goals, and adequate legal authority to pursue the goals. The coordination formulated by the Unified Economic Agreement called for removal of the barriers, termed imbalances, and the installation of the right parameters for established governance of the GCC as well as standard investment methods.

GCC members should also have full cooperation with each other that should reflect their interdependence. The relationship should become more intense, providing more cooperation and growth. The various policies on economics and fiscal should be geared towards the region and not on a national platform. Governments are forced to accept the impact of these changes on their economic and fiscal policies so that a greater cooperation is possible.

Is Monetary Union possible?

The GCC output is considered dichotomized; meaning output for the oil section and the non-oil sector are separate. Fifty-four percent is accounted for the non-oil section while 46% comes from the oil sector. The GCC economies encounter “symmetric shocks” in the oil industry which makes it reasonable to undertake a single currency and to peg this currency to the US dollar. As oil output is dealt in US dollar in the world market, they are affected by the same oil shocks.

As stated earlier, the GCC has to diversify. It can however use oil revenues to service the general public and in other investments. The purpose is not to “run a business” but to ensure that the money grows, and then let the private sector do the rest.

The GCC has based its currency on the dollar. But the dollar has recently reacted to inflation, and with this downfall the GCC individual currencies have been studied to be de-pegged in favor of other currencies like the Euro.

The studies on the suitability of a single currency in the GCC focused on the convergence aspect, particularly the inflation similarities among the GCC states, real GDP growth, fiscal deficits, tariff structures, financial standings, debt to GDP ratio, among others.

According to the study by Rosmy Jean Louis, Faruk Balli, and Mohamed Osman, shocks asymmetry were found with respect to the Euro which makes it not feasible for the GCC countries. But there is a correlation between France and Qatar in the matter of supply shocks. Adoption of a currency will have some cost for the GCC.

Another study to examine the preparedness of the GCC in forming a currency union was that by Zaidi who found “convergence in inflation rates” and reasonable distribution in the growth rates of the currency. Zaidi suggested that GCC states should have “coordination of monetary policies.” Dar and Presley also saw the “low level of integration” among the GCC countries which could be attributed to the countries’ oil-based economic structures. They suggested more acceptable rules for trade among the states and foreign direct investment, enhancing more coordinated production, enhancing privatization, and maximizing Saudi Arabia’s trade with the GCC instead of trading with other countries.

The best option for the GCC is to peg on the US dollar since the US military policy can help the GCC countries. GCC have used oil revenues for their respective development in infrastructure and other welfare services. Their common ethnic background, common language, religion, and labor mobility are some of the major hurdles in fighting asymmetric shocks which favor monetary union.

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to provide a critical analysis on the public expenditures of the GCC countries. Another was to find out how economics and finance affected the development of the six countries. These countries formed the GCC primarily for security reasons, but later this became an economic grouping.

In carrying out the objectives for this paper, this Researcher used review of the literature as a methodology. The literature on the Gulf Cooperation Council, the beginnings, the weaknesses and strengths, were gathered from books and journals and then analyzed to become a part of this dissertation. This Researcher provided an analytical study of the formation of the GCC and how public expenditures were carried out.

The founding of the GCC, along with the objectives and surrounding circumstances, was discussed in this paper. First, there were strategic reasons why this regional pact was formed. The states instituted programs in accordance with their respective platforms.

Bahrain was good at formulating Islamic government bills to coincide with Islamic monetary guidelines. It also followed the rules formulated by the FATF to defend itself from money laundering. Others like Kuwait made reforms by encouraging foreign investments. It also focused on population growth to increase their labor force. Kuwait provided budget for manpower development and training and increased the level of education of its labor force.

Oman made reforms in the banking sector and reformatted the Muscat Securities market to handle regulations, stocks exchange and deposits. Saudi Arabia bolstered financial markets and the stocks exchange. The United Arab Emirates started by building a strong federation. It established the stock market and a regulatory body to manage it. The UAE also strengthened laws on money laundering. Qatar made use of the money from natural gas to strengthen the banking sector and provided programs to improve liquidity.

The GCC spent much on education and training. The authorities have seen that education can provide more quality employment. Saudi Arabia provided the amount of $36.7 billion for education in 2010. Others followed by pouring more money on education and development of their workforce.

The GCC needs to define means and ways of attaining coordination of expenditure. This can be attained by eliminating the so-called imbalances which served as barriers to development, and by creating a picture of stability in the different disciplines within the member states. The GCC should also focus on developing on investment techniques by providing equal opportunity for the different sectors of production.

The goal of maintaining economic stability amid unstable oil revenues is one of the primary concerns of the GCC states. This is the reason why the countries have collectively diversified but were wise enough to use oil revenues for other purposes, like business and development of the economy and general welfare of the people.

Although they have worked collectively and cooperatively, the GCC countries have made efforts – and are gaining momentum – in investigating effective ways to reduce expenditures along with low revenues coming in the state coffers. It was suggested that the member states should be open with each other when it comes to proposed economic policies and provide a mechanism to monitor the effective implementation of those policies. At first, they can discuss the policies in broad terms but later they can provide precise implementations of spending and financing.

Effective coordination and cooperation means sharing information about the various public expenditure policies and implementations. This can provide many benefits on the economic policy of each member state. There are policies in various disciplines, such as civil service, salaries and the process of recruitment and employment that can be discussed in the regional level. This can provide enough knowledge and education to other member countries, and policies can be formulated along this line. Employees and policy makers from the different member countries can compare notes and information on expenditures in the different functions (social services, health, etc.) and see how they are being implemented. In the process, they can help each other; the more knowledgeable states can help the weaker and smaller ones, particularly if the “stronger” state had conducted intensive study about the services provided inside the country.

Moreover, with plans and projects on their way, the GCC has provided support, in several forms and ways, to domestic enterprises in the form of budgetary or financial aid. They may be in official GCC subsidies for private endeavor, such as production of foodstuffs, or loans to small-and-medium-scale enterprises, and other public utility expenditures. These moves can have big effects on the member states, as each one might endeavor to help and be a part of the larger group. This can also help in the equalization move for the members; providing for differential treatment, considering that, even if they have similar ethnic backgrounds, language, and familial ties, they still belong to different states; and providing for standard laws and policies for the members.

Another important subject discussed in the literature review is about public finance and public economics. Public finance is about government funding of the various projects for the public. It was discussed in the literature that a country is like a one big family that needs income to finance the various expenditures for the general public. The government supervises and uses the income generated from various businesses. The government programs and maintains the branches and departments. Public finance involves money and how this can be allocated and distributed to the different departments and welfare institutions. Public finance involves programming and planning the services and the allocation of resources and money for the general population.

Public economics, on the other hand, is concerned of policies and the implementation of these policies. Taxation is an important part of public economics. Public economics focuses on market forces and other matters pertaining to social security.

The GCC’s next big project is the creation of a monetary union or a single currency. Whatever will be the outcome, the theory of coordination and cooperation will work out and affect the outcome of this endeavor. There are many factors affecting the outcome or success of the creation of a monetary union. This was discussed in the literature review and provided ample conclusion and recommendations.

The GCC Charter has many implications about the future of the GCC. The objectives can be achieved if the member countries choose not to follow their own volition but on the path of the treaty’s ways to make the members walk in one direction. The Charter talks of the statutory limit on a country’s credit formulated by the banking sector. There are impediments and debatable issues regarding the credit limits to pave the way for fiscal coordination. A country can borrow from outside sources, if the bank has limits. But this has to be agreed upon by the member countries, if things should run smoothly. Moreover, there should effective monitoring mechanism, which is quite difficult to implement without the coordinated efforts of the member countries and the skill of the managers and employees assigned to do it.

Conclusions/Recommendations

The topic of public expenditure, public economics and public finance focuses on policies. Policies are about how they are planned and how they are to be implemented. Each area of government, each function and each implementation necessitate a standard mechanism to make it effective. On the GCC topic and the policies the authorities would like to implement, or possibly, currently implementing, all they need is a skill – the wise skill to implement these policies.

And what is this wise skill?

This was discussed in the literature – the subject of coordination and cooperation. If they have this, they can fail only very minimally. This is because through coordination and cooperation, they can have proper and effective communication. In every field of endeavor, communication is very important. Communication enables them to have shared policies. Shared policies will lead to other improvement. However, cooperation can be attained between the different member states. As to how that cooperation can be converted into different tasks within the GCC is another matter because it needs adjustment among the employees and managers in the different institutions within the GCC.

In the discussion, we focused on coordination and the sharing of information about policies being implemented in the different levels or departments in the GCC. They significantly need this because they are still beginning, and even if they are that old in business, they still need coordination and cooperation.

There’s still a long way for the GCC – a long way because they want to be big. This is the reason why they formed this alliance, or economic grouping, or whatever they call it. But all in all, the cooperation and alliance of the smaller states will pave the way for a bigger state or country. This is the trend in many other regions of the globe. They have different groupings and alliances that can empower and make them equal with other superpowers – economically and even militarily.

Bibliography

Abu-Qarn, Aamer S. and Suleiman Abu-Bader. “On the Optimality of a GCC Monetary Union: Structural VAR, Common Trends, and Common Cycles Evidence.” The World Economy 19, no. 1 (2008): 612-630. Web.

Al-Yousif, Yousif Khalifa. “Education Expenditure and Economic Growth: Some Empirical Evidence from the GCC Countries.” The Journal of Developing Areas 42, no. 1 (2008): 69-80. Web.

Anthony, John Duke. “The Gulf Co-operation Council.” International Journal 41, no. 2 (1986): 383-401. Web.

Bawaba, Al. “GCC Investment Strategy and Sectors Outlook for 2006.” Web.

Fasano, Ugo and Qing Wang. Testing the Relationship Between Government Spending and Revenue: Evidence from GCC Countries. Middle East: International Monetary Fund, 2002.

Fasano, Ugo and Zubair Iqbal. GCC Countries: From Oil Dependence to Diversification. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 2003.

Forstenlechner, Ingo and Emilie Rutledge. “Unemployment in the Gulf: Time to Update the ‘Social Contract’.” Middle East Policy 17, no. 2 (2010): 38-51. Web.

Ghanem, Abdeljalil and Said Elfakhani. “Privatization of Gulf Industrial Institutions: The Secret of Success.” Middle East Policy18, no. 2 (2011): 84-101. Web.

Heard-Bey, Frauke. “The United Arab Emirates: Statehood and Nation-Building in a Traditional Society.” Middle East Journal 59, no. 3 (2005): 357-375. Web.

Hossain, Amzad. “Development of K-economy in the GCC Countries: A Comparative Study on the GCC Countries and Asian NICS.” Web.

Hyman, David N. Public Finance: A Contemporary Application of Theory to Policy. Ohio: Thomson South-Western, 2008.

Kechichian, Joseph A. “The Beguiling Gulf Cooperation Council.” Third World Quarterly 10, no. 2 (1988): 1052-1058. Web.

Laiq, Jawid. “The Gulf Cooperation Council: Royal Insurance against Pressures from Within and Without.” Economic and Political Weekly 21, no. 35 (1986): 1553-1560. Web.

Looney, Robert E. “Structural and Economic Change in the Arab Gulf after 1973.” Middle Eastern Studies 26, no. 4 (1990): 514-535. Web.

Louis, Rosmy Jean, Faruk Balli, and Mohamed Osman. “On the Choice of an Anchor for the GCC currency: Does the Symmetry of Shocks Extend to Both the Oil and the Non-oil Sectors?” Int Econ Policy, no. 9 (2012): 83-110. Web.

Louis, Rosmy Jean, Faruk Balli, and Mohamed Osman. “On the Feasibility of Monetary Union Among Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries: Does the Symmetry of Shocks Extend to the Non-Oil Sector?” Journal of Economic Finance 36, no. 1 (2012): 319-334. Web.

Madra, Yahya M. and Fikret Adaman. “Public Economics after Neoliberalism: A Theoretical-Historical Perspective.” Euro. J. History of Economic Thought 17, no. 4 (2010): 1079-1106. Web.

Myles, Gareth. Public Economics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Premchand, A. Public Expenditure Management. Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 1993.

Ramazani, Rouhollah, K. The Gulf Cooperation Council. Virginia, USA: The University Press of Virginia, 1988.

Rhoades, Ellen A. “Literature Reviews.” The Volta Review 111, no. 3 (2011): 353-368. Web.

Shah, Nasra M. “Structural Changes in the Receiving Country and Future Labor Migration – The Case of Kuwait.” International Migration Review 29, no. 4 (1995): 1000-1022. Web.

Shoup, Carl S. Public Finance. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 1969.

Takagi, Shinji. “Gulf Cooperation Council: What Lessons for Regional Cooperation.” Asian Development Bank Institute, 2012. Web.

Winckler, Onn. “Can the GCC Weather the Economic Meltdown?” Middle East Quarterly 17, no. 3 (2010). Web.