Abstract

Projects are key factors in the improvement of numerous organisations and communities, as they contain the possibilities for advancing the companies’ outputs and creating additional services for the residents. However, to successfully design and implement a project, numerous considerations must be followed. Therefore, comprehensive knowledge about the project life cycle is expected from project managers, who drive the execution of such endeavours and are responsible for the attained results. As such, project managers plan, organise, allocate and control available resources, making sure that the initiation, planning, execution, controlling, and closure phases of the project’s life cycle are performed. The current report critically evaluates the stages of a project lifecycle, identifying instruments utilised to ensure successful completion and using the “Creation of a Community Recreation Centre Project” in Qatar as a basis. The report concludes that completing a given project requires a significant amount of effort and thorough preparation, which requires the use of specific instruments and strategical methods to ensure efficiency.

Introduction

Projects are instrumental drivers that help organisations to learn, enhance, change, and embrace new and innovative products, services, and processes. Projects can be part of normal daily operations or part of current ongoing processes that aim at making organisations better and more competitive in their respective sector. Successfully designed and implemented projects set strong foundations for perpetual achievements (Haass and Azizi, 2020). They facilitate future accomplishments by serving as a catalyst of change in addition to producing specific tangible or intangible and unique results. Although projects are important, their effective completion is not an easy endeavour. A series of tasks are involved in the process before reaching the completion phases of projects to ensure that needs of different stakeholders are met (Teoh, Zain and Lee, 2021). Comprehensive knowledge regarding the management of project phases or project lifecycle is essential regardless of the type or size of a project.

The project life cycle encompasses a series of stages that range from the starting to the completion date. Project managers plan, organise, allocate and control resources to ensure that projects go through all the phases successfully (Galli et al., 2019). The different stages that define a project life cycle include initiation, planning, execution, monitoring and controlling, and closure (Haass and Azizi, 2020). The primary objective of this report is to critically evaluate various tools and approaches involved in every stage of a project lifecycle and relate them to the Qatar government’s recreation centre project management. The report further draws information from the literature review regarding processes and procedures in the project lifecycle’s phases and applies the same in the government project management, changing and improving the Qatar population’s lifestyle and health. This paper also explains the successful implementation of all the phases of the project lifecycle using appropriate tools and techniques in relation to establishing a community recreation centre.

Analysing the Importance of Managing the Project Life Cycle

Critical Evaluation and Application of Project Initiation

Project initiation is the foremost phase of a project management lifecycle. According to Söderberg (2020), the phase determines the feasibility and value of a project. A meeting is held between the project managers and different stakeholders to understand the requirements, goals, and objectives (Söderberg, 2020). The activities involved in this state of project management lifecycle include undertaking a feasibility study and identification of project scope, deliverables, and key stakeholders.

Community recreation centres are vital in improving the quality of life. The centres offer valuable programs to all people, regardless of gender, age, or socioeconomic status, at minimised costs (Vanclay, 2017). A realisation of the invaluable benefits of the community recreation centres necessitates a considerable investment, ranging from human to financial resources (Hill, 2017). Notably, the programs offered in these centres are beneficial to both the body and mind, especially due to the physical involvement of the residents. For instance, according to Ruegsegger and Booth (2018), individuals who engage in regular exercises have reduced risks for heart diseases, high blood pressure, and diabetes and have increased longevity. Additionally, exercises help raise the level of white blood cells, strengthening the immune system.

Therefore, the government’s project to expand recreation centres should focus on managing and reducing non-communicable health conditions to improve the residents’ well-being. However, unavailability or inaccessibility to recreational facilities, especially in the urban and sub-urban areas, may also be contributing to the development of illnesses in the community. According to the Ministry of Public Health (2017), about 70.1 % of Qatari nationals are overweight, 44.9 % have more than two risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, and 17 % of adults have diabetes. The percentages show that ensuring a better life for individuals is required (Hill, 2017). Thus, the expansion of community recreational centres should be completed by including all stakeholders, their potential needs and engagement possibilities. The shareholders for the discussed community recreation centre project are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Identified shareholders for the chosen project

According to the results of identification, there are numerous entities and resident groups that could benefit from the establishment of a community recreation centre in Qatar. From this perspective, the project initiation step suggests that launching the community centre establishment could be a highly beneficial task for the described community. However, to ensure the success of this project, proper financing, controlling, and issue mitigation, suitable execution strategies must be identified after the scope of the project, and potential beneficiaries were determined (Sharon and Dori, 2017). This is typically completed during the project planning stage, the next step in the project life cycle.

The Project Planning Stage

Planning is the next phase after the identification of all stakeholders and defining the scope and value of the project. Sharon and Dori (2017) indicate that the planning phase of the project management lifecycle structures a set of strategies to guide everyone through subsequent stages. Project managers create programs that are helpful in cost, quality, time, changes, and risk management. The key components of the project planning phase are designing workflow documents, budget estimation, resource gathering, and risks anticipation (Sharon and Dori, 2017). In addition, a power-interest grid should be completed to map out the stakeholders.

First of all, the workflow documents step requires the creation of files that will outline the suggested procedures and their performance. Starting with a draft, this documentation should evolve into a comprehensive overview of the suggested project, its key phases, potential advantages and limitations, and expected outcomes (Abou-Senna et al., 2018). After that, the budget for the project can be estimated based on the proposed ideas and available support from the Qatar government (Cavalieri, Cristaudo and Guccio, 2019). While initially, the budget might contain only readily-available funds, additional resources might be included in the future, meaning that the possibilities for financing should also be incorporated into the estimation.

Resource gathering is another crucial stage of the planning phase, which allows the project manager to ensure that the necessary materials will be gathered for the execution stage. Although the types of resources might vary depending on the nature of the project, for the current project, the requirements are construction and management employees, sources of funding, and legal considerations (Orgut et al., 2020). These factors must be thoroughly outlined and researched to make certain that all necessary guidelines are followed according to Qatar employment and business law.

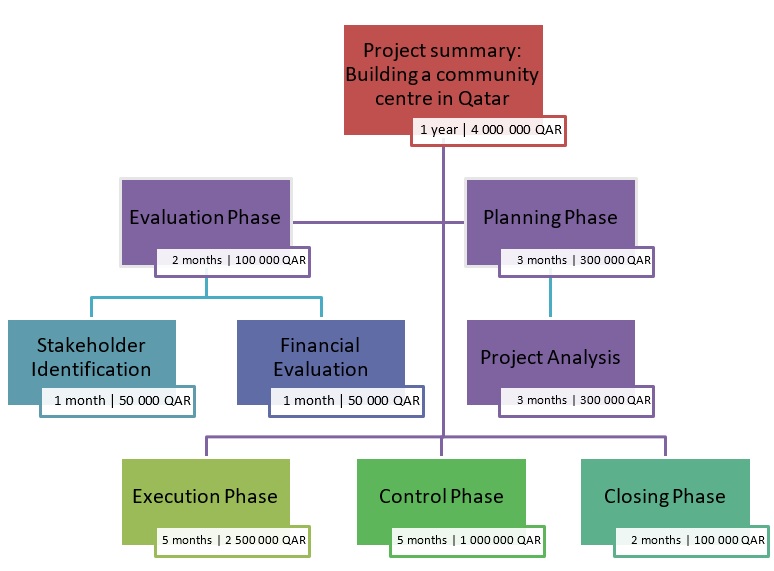

Finally, risks anticipation should also be completed during the discussed process. The project manager should extensively examine the project’s environment, creating a list of circumstances that might decrease the endeavour’s chances of success or even end it (Ahmad and Habib, 2021). For instance, in the discussed community centre case, approvals from Qatar government agencies and interest from the shareholders are essential aspects, which might also lead to such risks as disapproval or lack of involvement from the community residents (Smith and Hunt, 2018). Therefore, the manager is expected to portray a comprehensive picture of possible outcomes, explaining how these limitations might be mitigated prior to execution. Based on this information, a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) chart can be created, outlining the necessary steps. An example of a WBS chart is given in Figure 1.

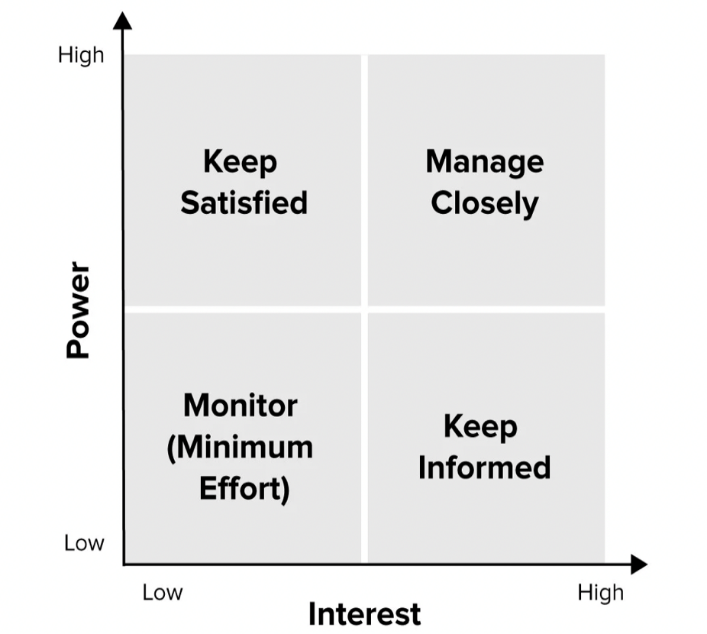

The power-interest grid is an instrumental tool used in stakeholder analysis to facilitate prioritisation. Every project impacts a wide range of people, some of whom may have the capability to advance or block them, while others may have contrasting interests (Bahadorestani, Naderpajouh and Sadiq, 2020). Therefore, project managers need to make prioritisation after classifying all stakeholders based on their power over the project and the interest they have in it. An example of a power-grid is presented in Figure 2.

The identified stakeholders for the proposed project are presented in Tables 1 and 2. These entities and community groups are directly related to the community centre’s success and must be deeply involved in the project in order to ensure its completion. However, to secure the engagement of these stakeholders, it is crucial to determine the strategies that could help them contribute to this endeavour (Bahadorestani, Naderpajouh and Sadiq, 2020). Therefore, several potential pathways that enhance their involvement are suggested.

Table 2: The stakeholders’ possible engagement procedures

For the different ministries that could be engaged in the project, the primary concern may be the provision of adequate support, such as financial, legal, and promotional, that could prevent the project from collapsing. Requesting grants, sponsorship, and financial aid is a beneficial approach to securing the engagement of these entities (Smith and Hunt, 2018). Based on the nature of the ministry’s focus and the available application methods, the project manager could determine which possibilities could advance the endeavour’s success.

The legal team is of special importance for the creation of a community recreation centre, as numerous permits and agreements should be obtained. As such, legal professionals could be involved on a pro-bono basis if the project is sponsored by the government; alternatively, the project’s funds must be utilised (Buckman et al., 2021). Typically, the legal team handles any complications connected to legal requirements, such as obtaining land documents, certificate of services provision, and more.

The research and statistics specialists should also be engaged in the execution of the given project, as the obtained knowledge could greatly enhance the project’s outputs. For instance, statistical information regarding the Qatar community residents is crucial for determining the types of services to be offered, which, in turn, influences the choice of the location, building, and other potential factors (Buckman et al., 2021). After that, research on the legal or business aspects of establishing a community centre in Qatar could be highly advantageous for the legal team and the project manager, simplifying their tasks and providing additional knowledge.

Another essential team to consider is the public relations department, whose involvement in the project’s execution could considerably improve the community’s awareness of the endeavour. As the community centre is to offer the services to the community residents, their knowledge regarding the provided facilities should be comprehensive and useful (Haugen et al., 2018). Thus, the public relations team should be engaged in creating a public awareness program, with the project manager directing the employees’ attention to the most significant details.

Finally, community leaders and the surrounding communities should also be involved in the project’s planning stage through requests for feedback and informational surveys. In Qatar, the community leaders can shed light on the residents’ needs and possible interests, ensuring that the created centre is relevant for the citizens (Vanclay, 2017). The surrounding communities could share their experiences in establishing a community centre (Vanclay, 2017). In the future, the individuals from other communities could also become the centre’s clients, meaning that their involvement can promote the overall efficiency and recognition of the establishment.

Executing the Project

After the planning phase of the project life cycle has been completed, it becomes possible to launch the project execution stage. During this step, the identified information and strategical ideas are performed under the control of the project manager, who ensures that the proposed methods are utilised thoroughly and appropriately (Kordi, Belayutham and Che Ibrahim, 2021). Typically, the execution phase is divided into three distinct processes: supporting the workflow, managing employees, and distributing project information (Kordi, Belayutham and Che Ibrahim, 2021). Each of these endeavours is essential for properly performing the execution phase and ensuring that the project will be completed in time.

Supporting the workflow is the first activity to be considered during project execution. Although the created strategic approaches and pathways might be comprehensive, they remain theoretical until execution, meaning that they must be aligned with each other. As such, the project manager should make certain that each of the involved systems is working efficiently, the departments are successfully communicating, and the overall workflow is not declined (Azhar, Khan and Zafar, 2019). After that, the second process can be initiated, where the manager should make sure that the employees involved in the execution tasks are committing to their responsibilities (Azhar, Khan and Zafar, 2019). If any problems occur, they must be handled to restore the endeavour’s outputs.

Finally, the distribution of information is necessary to mitigate potential risks and address arising issues. With the execution of the project encountering limitations and the growing activity’s scope, all shareholders, including the workers and potential beneficiaries, should possess relevant knowledge about the ongoing processes (Keshta, 2022). As the outlined tasks are being completed or delayed, the project manager should distribute this information to the interested parties or Qatar citizens.

Controlling for the Successful Project Completion

The next phase of the project life cycle is connected to the corrections needed to implement once the execution stage has been initiated. As the project is bound to encounter performance issues, such as a lack of necessary resources or unplanned disturbances, the project manager should be prepared to react to these novel alterations (Keshta, 2022). For instance, the manager could take corrective actions to diminish the impact of arising issues on the workflow, such as addressing opposing opinions from Qatar residents or managing the requests from the government.

Another feature of the controlling phase is its connection to the requirements established in the planning stage. While in the planning stage, the managers are expected to establish which Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) will be utilised to assess the project’s progress, in the controlling stage, the identified KPIs should be measured. The assessed indicators must be compared to their expected values, examining whether the project is executed according to the outlined scheme. If any potentially harmful deviations are present, for example, a delay in the timeline or the desired outputs, the manager is required to comprehensively evaluate the situation and establish the origins of the alterations. Failing to do so might result in grievous consequences for the project’s team, creating disruptions and hindering the completion of the endeavour. In a discussed community project scenario, such impediments might be delays in construction or the lack of qualified workers, which might prevent the manager from successfully reporting the project’s completion.

The Closing Stage

The final phase in the discussed process is the closing of the project, which allows to formally announce the completion of the planned activities. After the execution and controlling stages have been finalised, the project manager is entitled to determine whether project fulfilment can be announced (Alexander, Ackermann and Love, 2019). When identifying this, the manager is required to follow the analysis guidelines for clarifying closure, which include the consideration of budgetary expenses, utilised resources, tasks completed, and time management success (Caibula and Militaru, 2021). In addition, after the completion has been stated, it is expected to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the finished endeavour; examples may include early completion or unplanned costs accordingly (Caibula and Militaru, 2021). In the discussed community centre project, it will be vital to establish whether the centre will be able to perform according to the Qatar community’s needs or if additional projects must be created to ensure full coverage.

Conclusion

To conclude, the main phases of a project life cycle have been analysed in this paper, critically evaluating the beneficial strategical tools and techniques utilised during project initiation, planning, executing, controlling, and closing. It is evident that a significant amount of effort and comprehensive preparation is required to complete a given project, which necessitates the use of particular instruments and strategical methods to ensure efficiency. As projects can improve an organisation or community’s learning and changing processes, introducing new adjustments, project managers responsible for the completion of such endeavours must be aware of the project’s main phases.

Although the project life cycle typically starts with the planning phase, the initiation step, as identified in this paper, should also be considered prior to planning to ensure maximum productivity. Another crucial consideration is the inclusion of the Qatar shareholders’ interests and possible engagement options, which can tremendously enhance the project’s success and lead to beneficial results. By identifying potential stakeholders and involvement strategies, project managers can make certain that a needed number of resources and support is offered, resulting in a higher possibility of success.

In the current report, project life cycle phases were discussed from the perspective of creating a community recreation centre in Qatar. With eight possible entities and communities to be involved in the determined project, the manager can ensure proper financial support and interest from the Qatar residents. However, the project manager will be required to control for the appropriate execution, mitigate possible issues and evaluate the project upon completion. Based on the completed tasks and achieved results, the manager will be expected to present the outcomes of the project for the Qatar residents and the contributed inputs.

Reference List

Abou-Senna, H., Radwan, E., Navarro, A. and Abdelwahab, H. (2018) Integrating transportation systems management and operations into the project life cycle from planning to construction: A synthesis of best practices. Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition) [online], v.5 (1), pp.44–55. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtte.2017.04.006

Ahmad, M. and Habib, R. (2021) The role of top management as a moderator on project success during project life cycle. Journal of Quantitative Methods [online], v.5 (1), pp.111–135. DOI: 10.29145/2021/jqm/050105

Alexander, J., Ackermann, F. and Love, P.E.D. (2019) Taking a holistic exploration of the project life cycle in public–private partnerships. Project Management Journal [online], v.50 (6), pp.673–685. DOI: 10.1177/8756972819848226

Azhar, M.T., Khan, M.B. and Zafar, M.M. (2019) Architecture of an Enterprise Project Life Cycle using Hyperledger platform. 2019 13th International Conference on Mathematics, Actuarial Science, Computer Science and Statistics (MACS) [online], pp.1–5.

Bahadorestani, A., Naderpajouh, N. and Sadiq, R. (2020) Planning for sustainable stakeholder engagement based on the assessment of conflicting interests in projects. Journal of Cleaner Production [online], v.242, p.118402. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118402

Buckman, J.E.J., Saunders, R., Cape, J. and Pilling, S. (2021) Establishing a service improvement network to increase access to care and improve treatment outcomes in community mental health: a series of retrospective cohort studies. The Lancet [online], v.398, p.S28–S35. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02571-X

Caibula, M.N. and Militaru, C. (2021) Stakeholders Influence on the Closing Phase of Projects. Postmodern Openings [online], v.12 (1Sup1), pp.136–148. DOI: 10.18662/po/12.1Sup1/275

Cavalieri, M., Cristaudo, R. and Guccio, C. (2019) On the magnitude of cost overruns throughout the project lifecycle: An assessment for the Italian transport infrastructure projects. Transport Policy [online], v.79, pp. 21–36. DOI: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.04.001

Galli, B.J., Kaviani, M.A., Bottani, E. and Murino, T. (2019) An Investigation of the Development of Shared Leadership on the Six Sigma Project Life Cycle. International Journal of Information Technology Project Management (IJITPM) [online], v.10 (4), pp.15–78. DOI: 10.4018/IJITPM.2019100102

Haass, O. and Azizi, N. (2020) Challenges and solutions across project life cycle: a knowledge sharing perspective. International Journal of Project Organisation and Management [online], v.12 (4), pp.346–379. DOI: 10.1504/IJPOM.2020.111067

Haugen, S., Barros, A., van Gulijk, C., Kongsvik, T. and Vinnem, J.E. (2018) Safety and Reliability – Safe Societies in a Changing World. 28th European Safety and Reliability Conference, ESREL 2018 [online], Trondheim, Norway.

Hill, J. (2017) Why supporting patients to self-manage their diabetes in the community is important. British Journal of Community Nursing [online], v.22 (11), pp.550–552. DOI: 10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.11.550

Keshta, I. (2022) A model for defining project lifecycle phases: Implementation of CMMI level 2 specific practice. Journal of King Saud University – Computer and Information Sciences [online], v.34 (2), pp.398–407. DOI: 10.1016/j.jksuci.2019.10.013

Kordi, N.E., Belayutham, S. and Che Ibrahim, C.K.I. (2021) Mapping of social sustainability attributes to stakeholders’ involvement in construction project life cycle. Construction Management and Economics [online], v.39 (6), pp.513–532. DOI: 10.1080/01446193.2021.1923767

Mind Tools (2021) Stakeholder Analysis [online]

Ministry of Public Health (2017) Qatar Public Health Strategy 2017-2022 [online]

Orgut, R.E., Batouli, M., Zhu, J., Mostafavi, A. and Jaselskis, E.J. (2020) Critical Factors for Improving Reliability of Project Control Metrics throughout Project Life Cycle. Journal of Management in Engineering [online], v.36 (1). DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000710

Ruegsegger, G. and Booth, F. (2018) Health Benefits of Exercise. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine [online], v.8 (7), pp.1-15. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029694

Sharon, A. and Dori, D. (2017) Model-Based Project-Product Lifecycle Management and Gantt Chart Models: A Comparative Study. Systems Engineering [online], v.20 (5), pp.447-466. DOI: 10.1002/sys.21407

Smith, D.E. and Hunt, J. (2018) Indigenous Community Governance Project: Year two research findings. Australian National University: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR) Publications.

Söderberg, E. (2020) Project initiation as the beginning of the end: Mediating temporal tensions in school’s health projects. International Journal of Project Management [online], v.38 (6), pp.343-352. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2020.08.002

Teoh, C.H., Zain, Z.M. and Lee, C.C. (2021) Manufacturing organisation transformation – How customisation of project life cycle and project governance for custom solution enhances the chances of success. Asia Pacific Management Review [online], v.26 (4), pp.226–236. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmrv.2021.03.003

Vanclay, F. (2017) Project-induced displacement and resettlement: from impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development?. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal [online], v.35 (1), pp.3–21. DOI: 10.1080/14615517.2017.1278671