Introduction

Men of faith were highly reverend in early 20th century Russia when superstition and religion reigned supreme. The Romanovs employed several religious consultants and servants, whereas other nobles, royals, and upper-class individuals were captivated by occultism and mysticism. Although he had considerable charm, Rasputin was an enigma, a man of god hiding in the garb of an unclean, vulgar peasant. During the day, he acted as a spiritual counselor to kings, queens, and other members of the upper classes. He would prowl the city at night, drinking cheap liquor and looking for sexual partners. People found it disconcerting that someone with such a negative reputation gained access to the palaces of the Romanovs and their trust. Through 1916, Rasputin gained the notoriety of being a cunning manipulator who controlled the Tsarina, influenced ministers, and interfered with policymaking. The murder of Grigori on 30 Dec. 1916, inspired the Russian people to rise against the Romanovs to eliminate all that represented Tsarist Russia’s shortcomings.

The Rise of Rasputin

Rasputin had a meteoric climb in the preceding decade before his death, from being a relatively unknown Siberian holy peasant to one of the most influential characters in the Czar’s innermost circle. Rasputin was born in 1869 in Siberia in the rural community of Pokrovskoye (Harris). Notwithstanding a few run-ins with the law in his teens for misbehaving, he appeared destined for a normal life. He settled down with a local girl named Praskovya Dubrovina, had three kids named Dmitri, Maria, and Varvara, and helped in the family garden (Harris). Thus, on the surface, the Serbian preacher appeared to be a reputable family man.

The times Rasputin spent in a convent in 1892 were a turning point in his life and set him on the route to prominence. In 1905 he moved to St. Petersburg but never joined the monastic community, albeit earning the name “The Mad Monk” later in life (Harris). Unlike other men in Rasputin’s status, he maintained contact with his family. For instance, he brought his children to live with him in Saint Petersburg and continued to provide financial support to his wife (Harris). This action demonstrated that social norms did not constrain the preacher.

Rasputin’s religious zeal, mixed with an endearing personal charm, attracted the curiosity of Russian Orthodox clerics and later prominent figures of the Ruling dynasty, who presented him to Tsar II and his wife, Alexandra. Rasputin scheduled a meeting with Alexei’s mother after learning that the boy was critically unwell (Radcliffe 6). However, it remains unclear how Rasputin persuaded the Tsarina that he could lessen the child’s agony. Rasputin received a residence from the Romanovs in the city, and he started frequenting the Royal Palace. He routinely flirted with low-class prostitutes or attended wild parties while away from the Imperial family (Faulkner 8). Many women from the city received, according to multiple reports, not only spiritual instruction but also sexual favors from him.

Rasputin started to influence Alexandra, especially when the Emperor departed to head the troops during World War I. Gradually, Rasputin started bragging that he controlled the Tsarina, the monarchy, and the Russian government during his frequent pub trips. The city’s tabloids and communist propagandists found this interesting information. In 1912, Rumors began to spread that Alexandra had a romantic affair with Rasputin when one of her letters was published without her permission (Llewellyn et al.). In the letter, Alexandria described how she had kissed Rasputin’s hands and rested her head on his “blessed” shoulders (Llewellyn et al.). She further wished to sleep eternally on his shoulder and cuddle him (Llewellyn et al.). Indeed, these accusations against the empress were unsubstantiated rumors since there was no proof to support them. It is possible that this narrative was propagated to taint the unpopular family, further fueling the Russian people’s growing hatred for the regime.

The situation became much direr when the Tsar was called to the frontlines in September 1915. Before departing, he entrusted Alexandra with the responsibility of running the state. Many historians believe this to be one of Nicholas II’s several major blunders that led to the fall of the Romanov dynasty. Speculations were circulating concerning the German-born Russian queen’s possible treason to her country of birth, Russia. One theory holds that Alexandra sold the Germans Petrograd’s food supply via a middleman. In contrast, another holds that she had a radio transmitter in her bedroom and regularly spoke with Wilhelm II, the last German Emperor (Llewellyn et al.). These rumors and growing displeasure with the Serbian preacher’s affiliation with the Romanovs would continue for the following two years.

Rasputin’s Political and Governance Influence

When Alexei healed, Alexandra was convinced that the now infamous had the power to cure her sick son. Whether or not he had any control over Alexei’s health is disputed, but his impact on the empress was undeniable. The Tsarina had absolute faith in him; hence every time he acted excessively or rudely, he was given an excuse (Radcliffe 7). In Nicholas II’s absentia, Alexandra gained increasing influence over appointing ministers to the government. She relied on Rasputin’s advice when making government appointments, and he meddled in crucial matters (Walsh 291). The Serbian preacher knew no bounds, given his apparent holiness and lack of opposition.

Perhaps as a result of Rasputin’s suggestion, the Tsarina worked to ensure that no empire official would ever be able to oppose her husband’s rule. She replaced the experienced ministers with less dangerous, occasionally inept ones (Faulkner 8). They held their jobs because of their favor with the Tsarina, not their competence or usefulness. Even when Russia was at peace, this would have been a problem, but when Russia was at war, it was a disaster for both the royal family and Russia. Although there were several indications that the preacher was deceiving the Tsars, he had become too strong to be dismissed without offending prominent members of the royal family.

Rasputin’s requests that ministers he disliked be replaced with those he preferred had the most influence on the regime. He often used this to win the favor of his patrons and alcoholic friends. Rasputin would recommend a ministry dismissal or hire to Alexandra, and the Tsar would be persuaded to support it. The preacher sometimes offered guidance on matters of governmental and military affairs. Alexandra’s letters to her husband provide numerous illustrations, such as advice on army deployments and proposals for assaults on specific targets. Consequently, Rasputin fell out of favor with military leaders, including Nicholas Nikolaevich, who actively restricted the Tsar’s ideas (Harris). In August of 1915, Nikolaevich was fired, and Rasputin was undoubtedly a contributing reason for his removal (Faulkner 8). Unbeknownst to the Tsar, such actions painted an image of a ruler held captive and unable to make wise decisions.

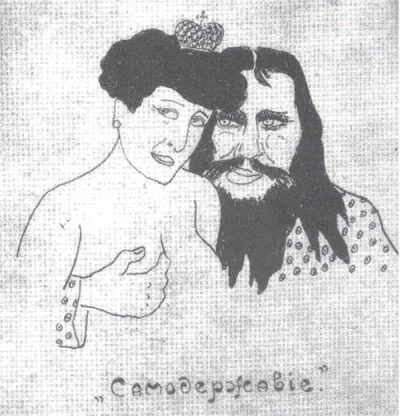

The consequences of this on Russia became clear in the long term. Russia had four different prime ministers, three different war ministers, and five different interior ministries in two years (1915-1917) (Llewellyn et al.). Rasputin’s orders resulted in the replacement of the vast majority. This leadership change destabilized an administration that was already shaky and struggling. On the contrary, Rasputin was a blessing in disguise for revolutionaries and socialists. They cited his political meddling and nighttime actions as proof that the imperial family was extremely corrupt and incompetent. Some publications and comics even had the Tsar under the preacher’s influence or grooving to his music (Llewellyn et al.). Figure 1 below depicts rudimentary evidence suggesting a sexual affair between Alexandra and Rasputin.

The Fall of Rasputin and The Russian Revolution

Unfounded reports about Rasputin’s tainted image spread, even among troops, as the war continued. Tales circulated that the preacher had collaborated with the enemy Germans, with one such rumor claiming that he had attempted to trigger a cholera outbreak in Saint Petersburg using “poisoned apples imported from Canada” (Harris). More influential than Rasputin’s actual opinions and deeds were the public’s perceptions of him, leading to calls for his removal from power by all means. In the Russian assembly, concern about the preacher was especially noticeable. Aristocrats who practiced conservatism were concerned that he could topple the empire (Harris). Several people were afraid that Rasputin’s interference was further debilitating a fragile monarchy and would ultimately lead to the defeat of Russia in the war (Llewellyn et al.). Indeed, it was evident that Rasputin needed to be eliminated.

Yussupov and his accomplices believed that if they could get rid of Rasputin, the Tsar would have a shot at redeeming the monarchy’s tarnished image. The preacher’s departure would make the Emperor more receptive to the counsel of his relatives, the aristocracy, and the assembly and less reliant on Alexandra (Harris). There was optimism that he would eventually return from his assignment at the command post and resume his role as governor in Saint Petersburg. In late 1916, a trio headed by Felix Yusupov devised a plot to assassinate the Serbian preacher (Llewellyn et al.). The starets were coaxed into coming to Yusupov’s palace in Petrograd, where he was given several glasses of alcohol and cakes that contained significant quantities of cyanide. When this strategy was unsuccessful, the three assassins shot the preacher multiple times before discarding his corpse in the freezing waters of the Neva River (Llewellyn et al.). This is considered the most accurate account of Rasputin’s death to date.

The above account is based on Yussupov’s memoirs published years before his death. In reference to the incident, Yussupov describes how the bad man who had been poisoned and shot in the heart must have been resurrected by the forces of darkness (Harris). Further, he describes his wicked resistance to dying as repulsive and horrible (Harris). Undoubtedly, the assassination of Rasputin was carried out with the intention of preserving the empire. Nevertheless, Nicholas II’s downfall was unavoidable, and nothing could have been done to stop it.

Rasputin had a murky reputation, reflected in the public’s varied reactions following his death. When the murderers emerged in public, the elite, from whom Yussupov and his accomplices were drawn, celebrated and cheered them. The common people wept for Rasputin due to his rise from a peasant to royalty, but they also saw his death as proof that the aristocracy had too much power over the Emperor. Much to the disappointment of Yussupov and his aides, Rasputin’s assassination did not fundamentally transform Nicholas and Alexandra’s policies. The emerging Bolsheviks saw Rasputin’s assassination as a real effort by the nobles to maintain power at the cost of the proletariat (Harris). That is to say, to some, the murder represented the systemic corruption that permeated the Royal palace. As far as they were concerned, Rasputin was the embodiment of everything wrong with the Russian empire.

Ultimately, chaos erupted in the capital, and senior politicians questioned the Tsar’s position. Milyukov was vocal in the Duma against the unsustainable monarchy (Walsh 125). The red flag of insurrection was spotted on Saint Petersburg’s streets 90 days after Rasputin’s murder. Even more concerning, the riots started before the grocery stores. The government was afflicted by a mental illness pandemic (Walsh 125). Alexander Protopopov responded with the whole arsenal of state repression in the last fury of authoritarian governance (Walsh 125). The city of Saint Petersburg was armed to the teeth, with machine guns perched on rooftops and street corners. 8 Mar. saw a massive street protest, during which Protopopov’s troops opened fire on the protestors (Walsh 125). In retaliation, the crowds slaughtered every law enforcement officer that came into their sight. Three days later, the Tsar sought to disband the Duma in absentia while at the army command center in Mohilev but failed. The crisis in St Petersburg had become so bad that Rodzianko, Head of the Duma, sent the Tsar the following message:

The position is serious. There is anarchy in the capital. The government is paralyzed. The transportation of fuel and food is completely disorganized. The general dissatisfaction grows. Disorderly firing takes place in the streets. A person trusted by the country must be charged immediately to form a ministry (Walsh 126).

The Tsar’s situation grew precarious, and other letters from Rodzianko demonstrated that even repression was ineffective at quelling popular discontent. In February of 1917, while the military effort was faltering and the civilian populace was in a state of desperation, a revolution spread over Russia and ultimately led to the Tsar’s abdication (Radcliffe 2). Nicholas and his entire household were assassinated a year later on orders from the new regime, which destroyed the Romanov Dynasty and its lineage.

Conclusion

Without a doubt, the Tsar’s downfall in the empire’s last days was hastened by the terrible judgments he made while under Rasputin’s control and the resentment that his existence stirred in the populace. Amid a serious crisis, the populace lost faith in their monarch. Russia was a participant in World War I and was suffering severe defeat. A lot of people back home were experiencing acute food and supply shortages. As trust in the government and the Tsar’s ability to protect its citizens eroded, revolutionary notions brewing in Russia for half a century finally came to light. Eventually, soon after Rasputin was assassinated, the Russian Revolution erupted, leading to the complete obliteration of the Tsar and his family.

Works Cited

Faulkner, Neil. A People’s History of the Russian Revolution. Pluto Press, 2017.

Harris, Carolyn. “The Murder of Rasputin, 100 Years Later.” Smithsonian Magazine. Web.

Llewellyn, Jennifer, et al. “Rasputin and the Tsarina.” Russian Revolution. Web.

Radcliffe, Jessie, “Rasputin and the Fragmentation of Imperial Russia.” Young Historians Conference, vol. 14, 2017, pp. 2-17. Web.

Walsh, Edmund A. The Fall of the Russian Empire: The Story of the Last of the Romanovs and the Coming of the Bolsheviki. Kessinger Publishing, 2010.