Introduction

In the environment of financial review, the efficient market hypothesis theory (EMH) is a general thinking which assumes that “the existing stock prices indicate the denomination of the business according to the materials available” (Shiller 23). This theory proposes that persons trading are not in a position to receive excessive gains within the information disclosed. Basically, this hypothesis operates on the facet of how the stock prices are distinguished by the pecuniary values. However, the key assumptions within the efficient market hypothesis are highly questionable.

For instance, the hypothesis alleges that stock returns are highly implausible since they are approximated from price movements. Among the antagonists of the efficient market hypothesis is Shiller Roberts. Same as the views of behavioral financial analysts, Shiller concurs with the impression that “market prices reflect animal spirits and passion, not perfect information” (Malkiel 63). This analytical treatise attempts to explicitly discuss the efficient market hypothesis criticisms by Robert Shiller. Besides, the treatise highlights the most important criticism using empirical data in order to establish its strengths and weaknesses.

Criticism of the efficient market hypothesis

As indicated by the efficient market hypothesis, the primary dynamic that contributes to price vacillations is the level of accessibility of inventive idea. Therefore, the hypothesis considers financial trade as proficient whenever the securities values respond immediately devoid of acknowledgment of the most recent data. However, Shiller totally refutes these arguments with series of rational explanations. Shiller supposes that as more data becomes available for scrutiny, there will be clear “certification of the fact that the efficient market hypothesis is ideally inefficient” (Shiller 12). The following are arguments fronted by Shiller to criticize the efficient market hypothesis.

Rational expectations

According to Shiller (2003), the first dilemma which cannot be verified by the EMH is that it assumes “all parties interested will have all the information available and create a rational expectation forecasts” (Shiller 91). In this case, the hypothesis proposes that all the trading persons possess homogenous prospect securities considerations. If this factor was to be true, Shiller then questions the intentions of the persons buying and selling in the market since trading basically “occurs when there are discrepancies in the market” (Grinblatt and Han 39).

In the financial review, the above concept connotes the ‘bulls and bears’ as applied in the stock markets. As opined by Shiller (2003), “it seemed to be almost like a mythology. The idea that people are so optimizing, so calculating and so ready to update their information, that’s true of maybe a tiny fraction of 1 percent of people” (Shiller 97). This percentage cannot represent the entire market. Therefore, Shiller dismisses the claim posted by the efficient market hypothesis that the market information is integrated in the same way by everyone. It is naïve to make an assumption that information is acquired avidly and processed perfectly by everyone trading in stocks.

Basically, a single stock buyer may predict that the worth of securities might increase, while the prediction of a merchant buyer for the same securities worth might be the opposite. Therefore, the assumption that all the modern traders have the right tools for accessing and acquiring similar and perfect information about the markets is a fallacy. This is a clear indication of a possible discrepancy in the interpretation of the information as received by different traders.

In fact, there is a clear indication that the predictions of each individual trader on asset prices cannot be random as insinuated by the efficient market hypothesis; it is defined “according to a certain individual’s knowledge and personal perceptions on the existing information on asset prices” (Hebner 19). Shiller concludes that human beings trading in the stock market are just avid customers who doubled up as story tellers based on individual insinuations. Shiller notes that “you can still memorize numbers, of course, but you need stories. For example, the financial markets generate tons of numbers but they don’t mean anything to investors” (Shiller 93).

The stock market and the buy and hold strategy

As indicated in the efficient market hypothesis, the “buying and holding approach is the same as any other strategy, thus, business generated processes in monetary markets do not exist” (Grinblatt and Han 41). This assumption basically insinuates that the decision to hold or buy stocks is similar to any other stock trading strategies. This is challengeable as discussed by Shiller who believes that the generated processes in businesses within the monetary markets actually exist. Shiller argues that similarity in the holding and buying of stocks cannot be similar since “entrepreneurs are the ones generating new ideas that spread information and in effect, create stock price rises and falls” (Malkiel 70).

In this case, Shiller (2005) opines that the rising in stock price is seen by individuals who are pulled towards buying them through a bandwagon effect. For instance, the surge in the stock market within the US at the beginning of the 1990s was basically as a consequence of psychological contagion which climaxed in irrational enthusiasm. Besides, the short-run patterns are as a result of the normal reactions by investors who are not sure or certain of any new information on stock prices. Therefore, “if the full impact of an important news announcement is only grasped over a period of time, stock prices will exhibit the positive serial correlation” (Malkiel 73).

Shiller disagrees with the claim put forward by the efficient market hypothesis that there is a specific way of earning supernormal returns. This assumption ignores the market dynamics involved in the action of either holding or buying stocks. In challenging this assumption, Shiller is categorical in stating that holding a conviction of being able to attract stock returns above the normal returns is but a dream. In supporting his position, Shiller (2003) opines, “it’s like some people can play in a chess tournament really well, but I’m not recommending you go into a chess tournament if you are not trained in that, or you will lose” (Shiller 89).

It is not very easy to pick the best performing stocks since the stock market is populated. Shiller suggests being realistic to balance the returns within the dynamics of the stock market. On the other hand, investments in markets with little competition from other investors may actually increase the chances of earning better returns. Therefore, it is illogical to argue that there is a particular formula for attaining supernormal returns (Malkiel 77).

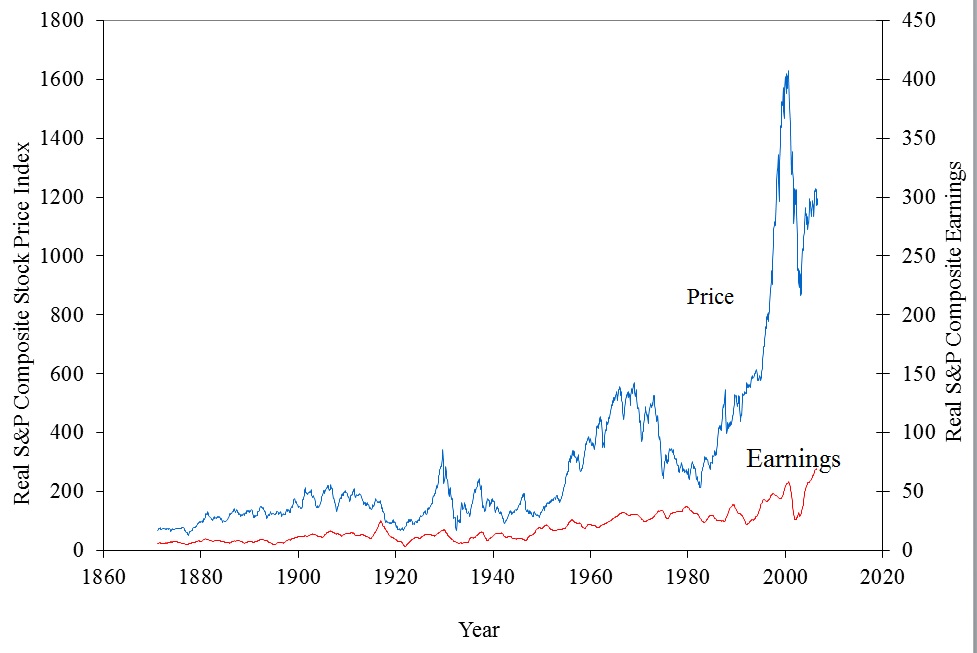

Testing the rational expectations: Irrational exuberance fronted by Robert Shiller

In order to confirm the irrational exuberance (inflation adjusted price/prior 10-year average inflation-adjusted earnings) as fronted by Shiller, the empirical experiment used stock data spanning for a century to predict the behavior of stock prices and earnings of the same period of time (Shiller 91). The price-earnings ratio was related to the S&P Composite Stock Price Index. Graphs were used to portray trend of various variables in the study over the period. The results were interpreted in comparison with ideal situations and interpretations are made based on the findings to advice on the relationship between stock prices and earnings from investments in stock in short and long term. This is summarized in the table below.

Key:

- Vertical axis: Left- Real S&P Composite Stock Price Index

- Right- Real S&P Composite Earnings

- Horizontal Index: Years of investment (ten-year periods)

From the above graph, the findings confirms the argument by Shiller that there is no way all the investors may acquire perfect information and used it in a similar way. Over a long period of time, it is not easy to predict the stock performance in a similar way. The prediction may vary as the earnings, even when several investors buy similar stocks. This is further displayed in the graph below.

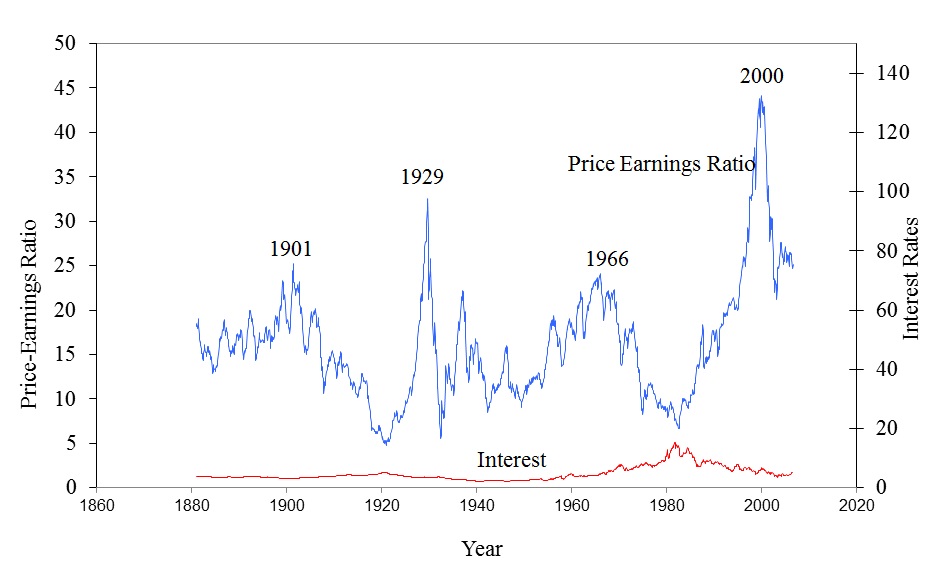

Key:

- Vertical axis: Price Earnings Ratio

- Right- Interest Rates

- Horizontal Index: Years of investment (ten-year periods)

Apparently, the price-earnings ratio displayed both even and uneven relationships with the interest rates over a long period of time. If the available market information was perfect, then all traders would experience same earnings from stock prices. The findings in the graph discredited the efficient market hypothesis’ assumption that all the modern traders have the right tools for accessing and acquiring similar and perfect information about the markets. In order to present clear information of stock price behavior of the ten-year period, the graph below offers an explicit review of the annualized returns against the price/earnings ratio.

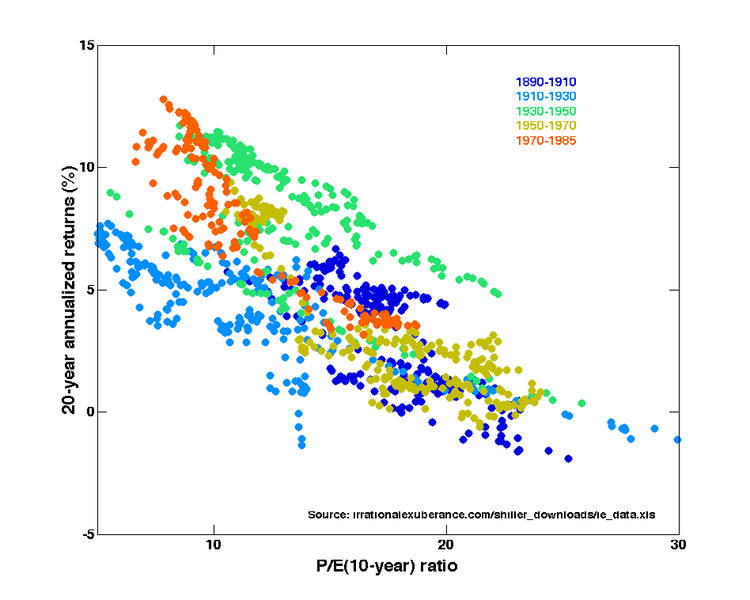

Key:

- Horizontal axis: Real price-earnings ratio

- Vertical axis: Geometric average of real annual returns after 20 years (the ten-year periods are colored appropriately).

Discussion

As stated by Shiller (2003), the above graph plot is a confirmation that the long-term stock investors (those who invest for a period not less than ten years) actually performed well when the stock prices were relatively low to earnings at the start of the 10 years. It is natural that each of the long-term investors would get private advice to “to lower their exposure to the stock market when it is high, as it has been recently, and get into the market when it is low” (Shiller 93).

Reflectively, the above correlation is not in line with the proposal by the efficient market hypothesis that the investors have full control of what the strategies at their disposal for attracting supernormal returns. This is the first strength identified. The finding has proved Shiller’s claim that holding a conviction of being able to attract stock returns above the normal returns is but a dream. It is naïve to ignore the market dynamics and decision sciences involved in the action of either holding or buying stocks.

Analysts state that “the market prices of the common stock are highly volatile and it’s likely to continue to be subject to wide fluctuations in response to a number of factors beyond the control of the investor” (Hebner 17). There are numerous factors that analysts consider as the prime cause of the volatility stock prices. First, the volatility is attributed to variation in periodic financial performance. Another factor is that working results and future anticipations often vary from the prospect of securities players who double as investors.

Therefore, it would be impractical to perfectly predict the future performance of stocks from the current stock market information that a potential investor may be in a position to acquire. From the results of the experiment using the empirical data, it is apparent that financial exchange is not proficient whenever the securities values respond instantly without acknowledgment of the most recent data that is available. An investor who bought stocks in 1980 would be in a position to earn admirable returns after the first ten years (Malkiel 70). This is the second strength identified.

This finding goes against the efficient market hypothesis which alleges that profiting is often exceedingly implausible since it is estimated from price variances. The results cannot discredit efficient market hypothesis assumption that the financial exchange can be proficient, whenever the securities values respond instantly without acknowledgment of the most recent data that is available since uneven performance is only noted in few instances (Grinblatt and Han 52). This is the weakness identified.

Conclusion

Robert Shiller’s criticisms of the efficient market hypothesis hold ground as was confirmed by the empirical experiment. Shiller’s concerns revolve around the perfectness and uniform application of stock market information by investors. Besides, Sheller offers a realistic analysis discrediting the theory’s assumption that the information on data to buy and hold stocks are within the reach of an investor who is interested in making supernormal returns. However, the findings could not discredit the efficiency of the financial exchange as alleged in the efficient market hypothesis.

Works Cited

Grinblatt, Mark and Bing Han. The Disposition Effect and Momentum, New York, NY: Wiley and Sons, 2003. Print.

Hebner, Mark. Index Funds: The 12-Step Program for Active Investors, Alabama: IFA Publishing, 2007. Print.

Malkiel, Burton. “The efficient market hypothesis and its critics.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 17.1 (2003): 59-82. Print.

Shiller, Robert. “From Efficient Markets Theory to Behavioral Finance.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 17.1 (2003): 83-104. Print.

Shiller, Robert. Irrational Exuberance, New York, NY: Princeton University Press, 2005. Print.