Introduction and Significance of the Study

Definition of Diabetes Type 2

Diabetes type 2 is a chronic disease that is characterised by high or low levels of sugar in the blood. The symptoms of this disease are frequent urination, excess thirst, constant hunger, and weight loss. The disease is mainly caused by genetic factors and a combination of lifestyle. Those that are caused by lifestyle can be controlled and include obesity, diet, and sometimes lack of sleep. People are advised to engage in physical activity, take balanced diet, avoid stress, and reduce food and drinks with high levels of sugar.

Health Effects of Type 2 Diabetes

Australia is the one of the first countries in the world that has good health. Nevertheless, diabetes mellitus has led to premature deaths, ill health, poor quality of life and disability in the country. This disease is also a major contributor to other diseases, such as coronary heart, kidney, vascular and stroke. An approximate of 13100 deaths in 2007 was from diabetes in Australia contributing 9.5% of all deaths to the country. Coronary heart disease has the highest number of deaths because of the diabetes.

Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes in Australia among Aboriginal People

According to the estimates of prevalence of this disease in the indigenous people conducted by National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS) and Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) showed that the ratio between indigenous to non-indigenous females 4.1 is higher than that of males 2.9. The reports also confirmed that prevalence of diabetes rises with age and the disease it is high in people with 45 years of age and more.

Necessary of Doing Study among Australian Aboriginal people

This study is important because indigenous Australians are at higher risks of type 2diabetes compared to the non-indigenous Australians. This is most in the indigenous Australians living in the remote areas (Kavanagh 2004, p.1011).

Different Ways to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes Related to Behavioural Change

National diabetes strategies have created programs to create awareness of this disease, for instance, the Live Life Well program, the National Diabetes Service Scheme (SDSS), and healthy living NT. These programs demonstrate, motivate, and educate the audiences on living healthier lifestyles to reduce the risk of diabetes, maintaining healthy weight, and becoming active to control the normal levels of sugar in the body (Eleanor et al. 2003, p.421).

Culturally Tailored Intervention

There are high chances of type 2 diabetes among the indigenous populations and this is links to the thrifty genotype. Other causes crucial to high type 2 diabetes in the indigenous population are the diets and levels of physical activity. The people in the indigenous areas tend to replace the nutrient dense diet with the energy dense nutrients with refined sugar and high fat contents. This disease develops from obesity that is by increased consumption of foods and drinks, such as snack foods, sugar-sweetened cool drinks, canned meat, and white bread. These people have less involvement in physical activities leading to overweight. This overweight or obesity facilitates the risk for acquiring diabetes type 2. People in the indigenous population are to take the traditional kind of foods, especially natural foods that are not processes.

The Aim of the Study

The aim of this study is to undertake a random research on the social aetiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus among Indigenous Australians as reflected by the health education programs.

Objectives of the Study

This paper aims at establishing whether culturally appropriate education programs in indigenous Australian settings would substantially ease the diabetes mellitus burdens: an approach-orientated study. The study will also determine why there are higher numbers of indigenous people, especially adults with type 2 diabetes and the behavioural changes required to reduce the risks of acquiring the disease in Australia.

Literature Review

The Gap Created Among the Australian Aboriginals

The conditions of diabetes mellitus can reduce in Australia by focussing on the nutrition and financial literacy of the indigenous communities. The government and investors have to ensure availability of fresh foods and employment among the indigenous people, such as vegetables and fruits because the community lacks the need for such foods. These foods are essential in reducing the risk of diabetes. The improvement of infrastructure in the communities would improve the lifestyle of the people in the communities and improve physical exercises that are important in preventing and managing the disease (Clarke 1998, p. 1245). Health education programs receive funding from the government. Nevertheless, the government should increase these funds to cover most of the areas in the indigenous communities (Crotty 2003, p.124).

According to Carry et al. (2001, p.47), health education programs are essential in communication to people about the causes of the disease, the prevention measures, management of the disease, and the cure. The programs play the role of creating awareness and influencing people to adopt the new changes in their health. This programs target the indigenous people because they have limitations in healthy living, and physical exercise because of high poverty levels and culture. An estimate of more than 51% however has taken the health education programs seriously as the rate of death increases in those communities (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2011, p.65).

Hypothesis of the Study

- H1. There is high prevalence of diabetes type 2 among the Australian Aboriginals

- H2. Diabetes type 2 is by lack of nutrition and financial literacy of the indigenous communities

- H3. Health education programs are essential in communication to people about the causes and prevention of the disease

Methods

Kind of Study

As one of the most important components of Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT), a search of literature is not easy to undertake as it includes pre-test and post-test study (Glasziou 2001, p.124). A RCT involves searching all the evidence relevant to the research question. Key steps of the random literature search must deploy using appropriate keywords, searching all the databases, considering grey literature and unpublished articles while applying search filters (White & Schmidt 2005, p.45). Of course, starting with currently available RCT would be a worthwhile effort. Various biomedical databases should be considered and include PubMed, EMBASE and ScienceDirect (Higgins, Green & Cochrane Collaboration 2009, p.134).

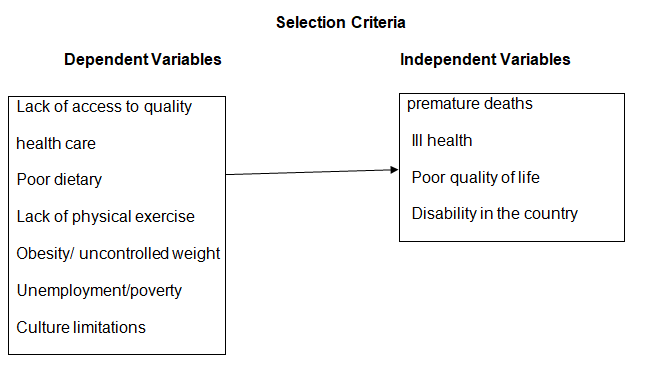

To ensure a randomly research process with academic comprehensiveness, there are several rules to obey. First, randomly place questions into categories and to search further information on the topic is important. A tactical method is to utilise the conceptual framework diagram to cover every area as well as the overlapping parts (Egger et al.). Secondly, the manipulation with the possible keywords synonyms is essential, as biomedical terminologies could be interchangeable for some topics (Damin et al. 2007, p.15). Thirdly, the search of unpublished literature, ongoing studies and grey literature is critical in order to minimise the publication bias. Last, it is necessary to comply with the research protocol to avoid missing essential information and ensure completion of the research process within the time allocated.

This research will take a random approach that will entail the researcher working from a known hypothesis that culturally appropriate education programs in indigenous Australian settings would substantially ease the diabetes mellitus burdens. Therefore, the study takes a top down approach.

To realise the use, explanatory approach, RCT test efficacy tools of collective and analysing data like questionnaires and interviews were used. RCTtools were preferred because they enable the researcher to come up with facts like a hypothesis that culturally appropriate education programs in indigenous Australian settings would substantially ease the diabetes mellitus burdens and thereafter testing and confirming the hypothesis (Glasziou 2001, p.138). Lastly, data in RCT research are hard and reliable where data collected is rich and deep (Quinn, 2002, p.219).

In addition to the above, this study takes a test kind of philosophy that culturally appropriate education programs in indigenous Australian settings would substantially ease the diabetes mellitus burdens. A test approach will make us understand more the impact of culturally appropriate education programs in indigenous Australian settings on diabetes mellitus burdens. There are no biases in this research (Miles and Huberman 1994, p.12).

Sampling

Sample Plan

The population of study in this research will be the two groups of Indigenous and non-indigenous Regions across the country. Every element of the population is important and should be studied. As these are big areas, I thought I could choose the most populated local area of the two and that is Playford in Australia, and base my focus groups in this place. A response-adaptive randomization will select the groups in the research process. The choice of the two elements to be studied is by sampling techniques. Sampling enables the researcher to study a convenient size of the population depending on the research he is conducting and the constraints (Miles & Huberman 1994, p.27).

Due to the challenges for this study, the researcher chose to use response-adaptive randomization sampling technique to select his sample of study (Catherine et al. 2011, p.23). The Australian health sector under study is a large industry and it has several companies dealing with the information technology. That would give me areas across a few different states. And then I would run focus groups in each state until I reach saturation.

Reputable health organisations with good corporate governance that the researcher has ease of accessibility and ease of collecting data will be selected for the study. The researcher will book appointments with the top management from the company for conducting interviews concerning the effectiveness of culturally appropriate education programs in indigenous Australian settings diabetes mellitus. The interviews as a method of collecting data will be made more effective since the researcher with the aid of his research assistants will collect data (Craig, Hattersley & Donaghue 2009, p.211).

Sample Size

The sample population will comprise of 1,000 people and only 100 will participate in the study. The response-adaptive randomization will choose the sample size where the two groups under study will be covered. The groups will constitute of 50 people on each to eliminate any chances of bias in the study. G-power will divide the participants randomly.

Research Sit and Participants

Projection by 2025 shows that more than 12 million adults at the age of 25 years will be at risk of acquiring diabetes if no changes are made to address the issue. The rising number is because of increase in type 2 diabetes as the people have changed to poor diets, ageing of population increases, reduction of physical activity, and the increase in the epidemic of obesity. This disease will affect indigenous communities at most and the nations economy. The communities need to recognise the disease as preventable to maintain good health of the people. The people in Playford will make the potential participants for this study as the area contains remote and non-remote areas. The people there need education on the disease, as the ratio is 2.1. The participants will be randomly selected from those with the disease.

Implementation of the Study

Questionnaire

The question will be on:

- What has been done to help curb the problem of diabetes in the indigenous communities?

- Who funds these programs?

- What are the main reasons for high numbers of people with type 2 diabetes in the communities?

- What is the outlook to this disease in Australia and especially to the indigenous community?

- What is the current situation of indigenous people in Australia and the rights they have to quality health care?

Data Collection Methods

Data collection is the precise, random gathering of information relevant to the research purpose or the specific objectives, questions, or hypothesis of a study (Canuto, McDermott, Cargo & Esterman 2011, p.133). The various methods of collecting data will vary depending on the approach that the study is using and they range from interviews, questionnaires, observations, documentation among others.

On the other hand, there are also primary and secondary methods of collecting data. Primary methods of data collection are the methods that collect data for the first time while secondary methods are those where the researcher uses data collected by other people. According to Bryman and Bell (2007, p. 10), secondary data collection methods refer to the ability of the researcher to carry out an analysis of the data that has already been prepared by other researchers. This research will use both primary and secondary methods to collect data for the study. The primary sources of data will come from interviews that will be conducted by the researcher using a questionnaire (Bruce, Davis, Cull & Davis 2003, p.85). Focus groups will be established and used to conduct the survey.

The secondary sources will include review of both published and unpublished literature related to the implications of culturally appropriate education programs in indigenous Australian settings on diabetes mellitus, while the primary sources will include the review of the findings from the responses from the interview conducted by the researcher (Jankowicz, 2005). Through the interviews, the researcher collected data on the collaboration of the various departments in the health sector and the importance culturally appropriate education programs in indigenous Australian settings and their impacts on diabetes mellitus (Creswell 2007, p.49).

Data Analysis

Responses to the interviews and questionnaires will be analysed using thematic analysis. This tool is considered to be highly inductive, as themes are not imposed on data by the researcher but rather emerge from the data itself. In this method, data from different people are compared and contrasted, similarities and differences identified in a process that continues until the researcher is satisfied that no more new issues or themes are arising (Flick et al. 2004, p.35).

Thematic analysis was chosen because it allows rich, in-depth, and detailed meaning to be derived from the collected data. It involves coding of data according to the emerging themes (Miles & Huberman 1994, p. 56). This tool categorises the findings and conclusions from various sources, according to the emerging themes, making it possible to identify similarities in the meanings and explanations from the various respondents. The researcher is also able to highlight the main issues emerging from the responses. Line by line analysis allows the researcher to highlight matching patterns in the text from the different responses allowing quantification of data (Salkind 2008, p.67).

Ethical Issues

Finances, time, and uncooperative respondents will be the main limitations of the study. The respondents have high resistance of health education programs making it difficult to acquire clear evidence on the situation at the indigenous communities in Australia. Most of the information gathered is not sufficient to make analyses on the situation in the community. Overreliance on the secondary sources of information increases the chances of acquiring data that were not effectively evaluated limiting the reliability of the data. The use of secondary data is mainly because of financial and time limitations. Time, finances, and information available from the respondents also limit the primary data acquired.

Time Line

Budget

List of References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2011, Diabetes Mellitus. Web.

Baker, P et al. 2011, Community wide interventions for increasing physical activity, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, New York.

Braun, B et al. 2000, ‘Risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease in young Australian Aborigines, A 5-year follow-up study’, Diabetes Care, vol.19, pp.472-479.

Bruce, DG, Davis, WA, Cull, CA & Davis, TM 2003, ‘Diabetes education and knowledge in patients with type 2 diabetes from the community: the Fremantle Diabetes Study’, J. Diabetes Complications, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 82-89.

Bubben, H & Beck- Bornholdt, H 2005, ‘Random review of publication bias in studies on publication bias’, BMJ, vol.331, pp. 433-434.

Canuto, KJ, McDermott, RA, Cargo, M & Esterman, AJ 2011, Study protocol: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial of a 12-week physical activity and nutritional education program for overweight Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Web.

Carry, R et al. 2001, ’Long-Term effectiveness of a quality improvement program for patients with type 2 diabetes in general practice’, Diabetes Care, vol. 24, no.8., pp. 1365-70.

Catherine, C et al. 2011, ‘Diabetes in pregnancy among indigenous Women in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: A method for random review of studies with different designs’, BMC Pregnancy and Children, vol. 11, pp.104.

Clarke, A 1998, ‘The qualitative-quantitative debate: moving from positivism and confrontation to post-positivism and reconciliation’, Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol.27, no.6, pp.1242-1249.

Craig, ME, Hattersley, A, Donaghue, KC 2009, ‘Definition, epidemiology and classification of diabetes in children and adolescents (Review)’, Pediatr. Diabetes, vol.10, no.12, pp.3-12.

Creswell, J 2007, Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches, Sage, London.

Crotty, M 2003. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process, Sage, London.

Damin, S et al. 2007, ’Delivery of preventive health services to Indigenous adults: response to a systems-oriented primary care Quality improvement intervention’, MJA, vol. 187, no.8, pp. 453-457.

Daniel, M, Rowley, KG, McDermott, R, Mylvaganam, A & O’Dea, K 1999, ‘Diabetes incidence in an Australian aboriginal population: An 8-year follow-up study,’ Diabetes Care, vol. 22, no.12, pp.1993-1998.

Edgewood College 2011, Writing a review on the literature. Web.

Egger, M et al. 2008, Random reviews in health care meta-analysis in context, , John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken.

Eleanor, M et al. 2003, A new approach intervention programme to prevent type 2 diabetes in New Zealand Maori’, Asia Pacific JClin. Nutr., vol.12, no.4, pp.419-422.

Flick, U et al. 2004, A Companion to qualitative research, Sage, London.

Glasziou, P 2001, Random reviews in health care: a practical guide, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Higgins, JPT, Green, S & Cochrane Collaboration. 2009, Cochrane handbook for random reviews of interventions, Wiley-Blackwell, New Jersey.

Jain, S 2006, Emerging economies and the transformation of international business: Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRICs), Edward Elgar Publishing, New York.

Jankowicz, A 2005, Business research projects, Cengage Learning, New Jersey.

Kavanagh, J 2004, Integration qualitative research with trials in random review. BMJ, vol. 328, pp.1010-12.

Leedy, P & Ormrod, J 2005, Practical research: planning and design, Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

Miles, M & Hurberman, M 1994, Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook, Beverley Hills, London.

Quinn, M 2002, Qualitative research & evaluation methods, Sage Publications, New York.

Salkind, N 2006, Exploring research, Pearson-Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

Saunders, M, Lewis, P & Thornhill, A 2007, Research methods for business studies, Pearson Education, Boston.

White, A & Schmidt, K 2005, ‘Random literature reviews’, Complement Ther Med, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 54-60.

Yin, K 2003, Applications of case study research, Sage, London.