Introduction: The Trend of Strikes in the UK for the Past 40 Years

The unemployment rates in the UK – that is, the number of people without a formal source of income who have been seeking employment and are ready to work – have decreased over the past decade. According to the Office for National Statistics (2021), the UK labor market continues to recover, with over 29 million people formally employed. That means that a bigger amount of people now may want to resort to strikes in times of needs. Strikes in the UK involve trade unions, championing better workers’ workplace conditions, such as pay increases and adequate rests; however, for the past 40 years, strikes have been fewer due to legislative barriers. Schooled by the events of the second half of the 20th century, the British authorities have tightened their restraints on strikes activities. Nevertheless, they had to learn to be more responsive to the needs of workers, who now need to turn to other measures to express their distaste.

Reasons for Great Decrease in Strike Levels

A reduction in strikes is a good factor for any country’s political and economic development. On the contrary, however, mass strikes increase the workers’ political awareness, confidence, and self-coordination. They help illustrate the essence of collective action; thus, giving definite evidence that socialism is a feasible option to replace capitalistic inequalities. Currently, the UK experiences fewer strikes than in any moment in its history. Low levels of strikes characterize the period from the 1990s – that is, in every particular year from 1991 on, there have been fewer strikes compared to any year before that time (European Trade Union Institute, 2016). According to Chandler et al. (2018), diminished confidence in employees usually causes low levels of strikes. That leads to the conclusion that policy changes in the 1980s reduced workers’ morale and changed the essence of employment places industrial relations.

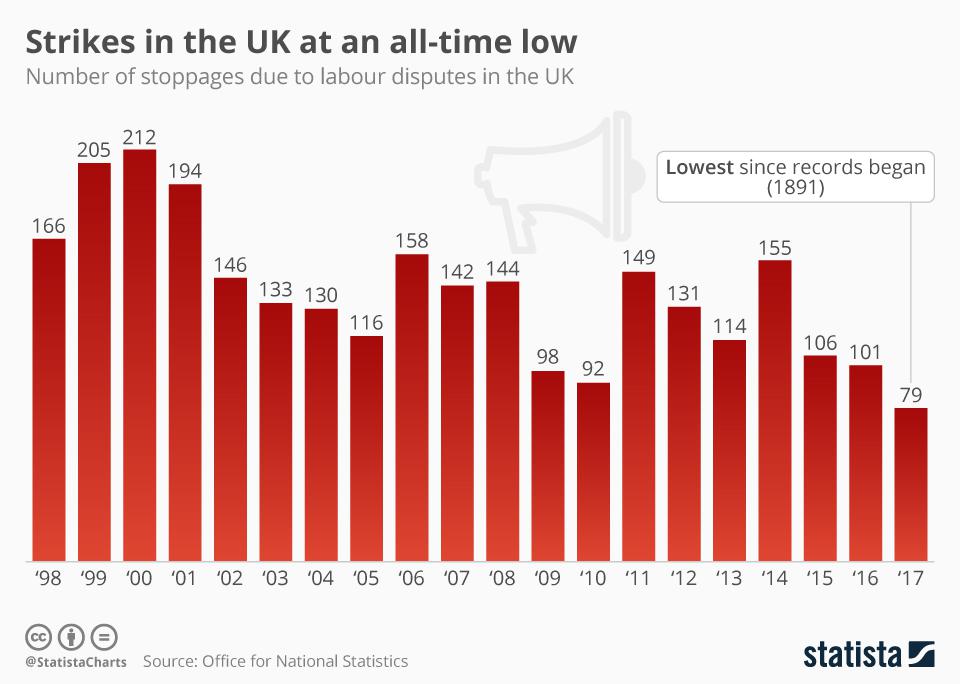

When it comes to analyzing other reasons behind the current level of strikes, what needs to be mentioned is the economic factor. Economic breakdown and collective industrial action are reported to be directly related (Pohl, 2018; Cullinane, 2018). Moreover, according to Gall and Kirk (2018), the strike activity is deficient owing to the Tory Trade Union Act of 2016. As shown in the Appendix A, there are fewer stoppages per year resulting from labor disputes compared to two decades ago (Armstrong, 2018). Essentially, employee unions now use other means of conflict resolution and expression of workplace grievances; and that has proven to yield good results to workers.

Outline of Factors Contributing to Strikes in Recent Years

Many reasons motivate strikes at the individual, local, national, and international levels. Workers, through their unions, seek to better the conditions of their workplaces. For instance, they want to earn better pay or increased wages or protect their incomes from decreasing. They could also be pursuing shorter working days at a maintained payment. Additionally, strikes could happen due to people’s dissatisfaction with employment terms and conditions. For instance, they might perceive their company to be using unjust policies in its operations; unfairness is a significant cause of strikes in the United Kingdom. Inadequate incentives or remuneration terms cold increase the urge for strikes to happen as well. Organizers of strikes have always championed against individuals’ inappropriate or unlawful discharge from their workplaces. Some cite a need for workers to have leaves with wages, rests, and special employment privileges; withdrawal of any right or privilege often leads to industrial action. Poverty, inequality in employment, employment of foreigners at the expense of locals, and the fear of getting retrenched all lead to strikes.

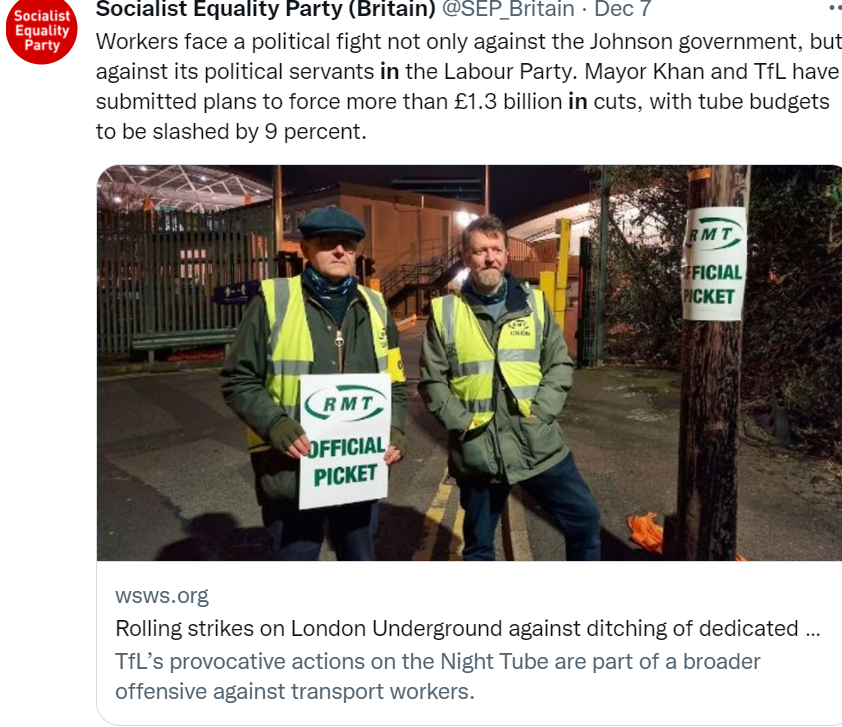

Rail, Maritime and Transport trade unions have conducted recent labor collective actions to prevent proposed changes to their functions, especially for the train conductors; this has been witnessed among train drivers on the Southern Rail. According to European Trade Union Institute (2016), the UK offers no option for striking, even though industrial legal actions are legitimate and guaranteed protection by British law. Large-scale public domain go-slows of 2014 led to a loss of 78,000 working days compared to 180,000 working days in 2015 (European Trade Union Institute, 2016). Additionally, as European Trade Union Institute (2016) states, pay-related complaints made 2015 strikes frequent in the education sector; generally, since 2004, most strikes have been due to pay, except for 2009 and 2010, when redundancy caused them. Therefore, as one can see, nowadays workers use the means legally available to them to express their concerns.

Factors Influencing Strike Activity in the Public Sector

The public sector has experienced many strikes in history; several factors influence that. According to Chiripanhura and Wolf (2019), the growth of public employment results from the development of central and local governments. For instance, public sector employment grew after the Second World War, majorly because of the nationalization of parts of the economy such as coal mining, rail industry, and other public utilities. Chiripanhura and Wolf (2019) claim that the year 1979 recorded the highest level of public sector employment with over seven million individuals, implying 28.1 percent of UK employment. However, it decreased to about 18.6 percent in the following two decades, reflecting about five million in 1998 (Chiripanhura and Wolf, 2019). Then, as stated by Chiripanhura and Wolf (2019), in the 2000s, work rates in the public sector increased significantly again – until 2008, when the UK suffered an economic downturn, resulting in only 5.36 million people employed there. Appendix B cites some of the austerity measures imposed by the British government to contain the budget deficit, reducing public employment. Evidently, such measures are not favored by the workers and that is one of the reasons for them to strike.

Factors Influencing Strike Activity in the Private Sector

Research proves that the UK’s private sector has been growing since the 1980s. That is, it grew by over 50 percent between 1983 and 2018 – in 1983 it consisted of about ten million workers, comprising 96 percent of jobs in the UK (Chiripanhura & Wolf, 2019). Now, according to Chiripanhura & Wolf (2019), the ratio has changed; as of 2018, there are 27 million employees in the private sector; thus, 83.5 percent of employment is taken by the private sector. Accordingly, such a large number of people will always have their reasons to take strike action in cases of dissatisfaction and expect to be heard, since it is difficult to ignore masses of that scale.

Significance of Low Levels of Strikes

Trade Unionism and the Defense of Workers’ Interests

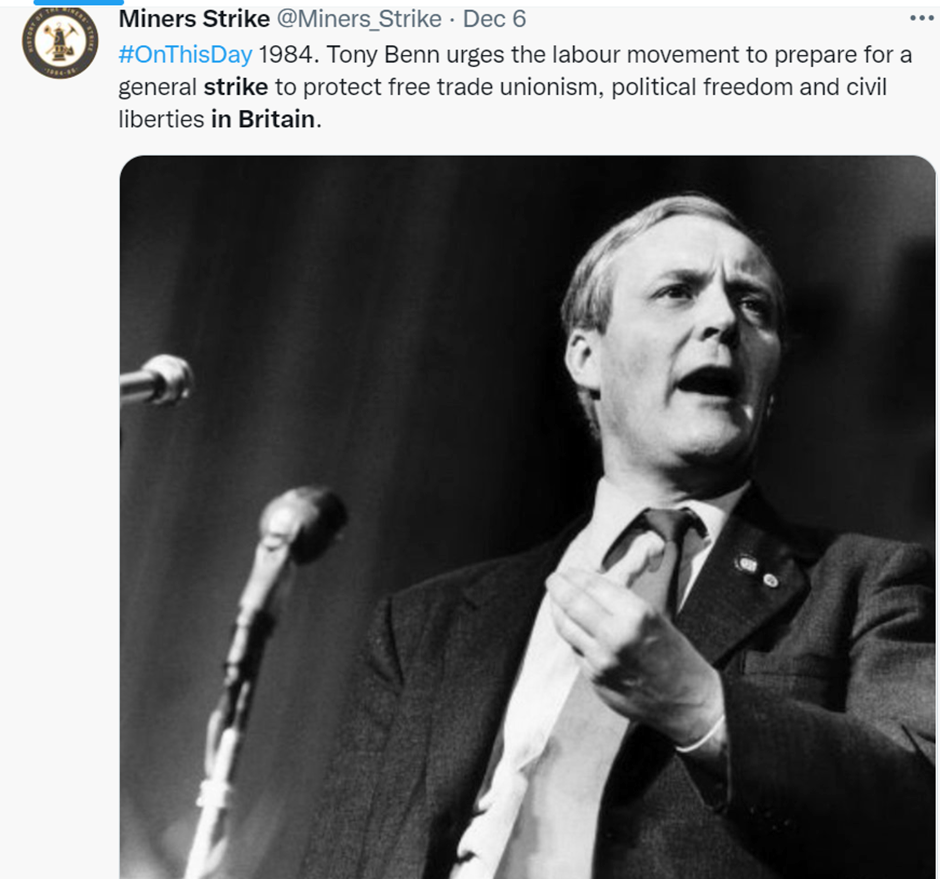

Trade unionism has declined since the 1980s, owing to obstructive public policies that legislators pass. According to Chiratos (2018), the Trade Union and Labour Relations Act of 1992 and the Trade Union Act of 2016 have hindered the capacities of industrial movements in collective bargaining and coordination of industrial actions. The decrease in trade unions’ membership from the 1970s shows clearly that their popularity is diminishing. Many individuals do not see the essence of trade unions because they do not recognize fortified union power. On December 6, 1984, as shown in Appendix C, Tony Benn advocated for a strike to champion freedoms and civil rights – that is, Miners Strike. Proper working conditions guarantee a successful or desirable career line and general welfare for an employed individual (International Labor Organization, 2016; Appendix D). Indeed, the function of trade unions ought not to be downplayed, for they promote just treatment at the workplace and removal of discrimination

Nature of Employment Relationship

The Conservative Party aimed at regulating trade unions to restore political and economic stability after the numerous strikes of the 1970s. It attempted to control the labor market, to enhance competitiveness and enterprise habits in the UK. According to Chiratos (2018), the Conservative government employed interventionist policies to minimize trade unions’ political supremacy and manage them through the Trade Union and Labour Relations Act of 1992. As much as the international labor policy framework permits the establishment of trade unionism, the UK limits them instead of supporting them.

When turning to the current situation, everything was in relative order until the coronavirus struck. As per Mangan* (2020), February 2020 statistics show that employment in the UK was at 76.6 percent, and unemployment was at 4%, with about 1.36 million people unemployed; economic inactivity was low – at around 20 percent. The regular pay rate increased to 3.9 percent in April 2019 but later slowed to 2.8 percent between December 2019 and February 2020. According to Mangan* (2020), the coronavirus pandemic heavily affected workplace conditions: for instance, employees’ pay decreased by over two percent, and employees claiming benefit increased to 2.8 million. The government consulted with Trade Union Congress (TUC) and other worker groups and had to set aside some of the 330 billion Great Britain Pounds to cushion employment relations (Mangan*, 2020). This adds to the evidence that the pandemic has hit the economy hard, and extra measures had to be implemented.

Case Studies

The Three-Day Week

The name of the Three-Day Week is derived from the order by the British government authorities to limit electricity usage to only three days. According to Gall and Kirk (2018), the Conservative government introduced it around 1973 to ration electric power, which could hardly be generated due to the strike done by rail workers and coal miners. The government specified days for electricity usage, but the restrictions were eventually lifted in early March 1974 (Gall and Kirk, 2018). However seemingly cruel, authorities sometimes saw no other way to regulate the strikes’ consequences.

Coal power stations generated most of the UK’s electricity in a significant portion of the 20th century, and the government sought to conserve coal by reducing the consumption of electricity. The Fuel and Electricity Control Act of 1973 included the Three-Day Work Order enforced from December (International Labour Organization, 2016). The system reduced miners’ salaries; thus, the National Union Movement members organized a national ballot on industrial action. The majority of the voters supported the strike, which involved coal miners, who were significant generators of electricity in the United Kingdom.

The British economy experienced increased inflation levels in the 1970s; as a result, the government placed caps on public and private sectors. Trade unions and most workers were discontented with the measures taken, for their wages and salary increments did not operate at par (Chiripanhura & Wolf, 2019). Coal miners, trade unionists, and other vital industrial players conducted strikes; for example, the National Union of Mineworkers became more radical towards pressing for wage increments and a socialist environment. Elections that followed were unique; the Labor Party attained more positions in the House of Commons, and Harold Wilson retained power with a minority.

The Winter of Discontent

Between November 1978 to February of the following year, often called ‘The Winter of Discontent,’ the United Kingdom experienced numerous sectors from trade unions and the public and private sectors. Organizers of the strike advocated raising employees’ pay higher than set limits. For instance, employees of Ford held a strike in 1978, leading to a 17 percent increment of their salaries (International Labour Organization, 2016). Road haulers, garbage collectors, many other public servants, and gravediggers operating from Tameside and Liverpool also refused to work as usual.

The Labor Party equally had internal divisions on socialism and labor law reform; thus, casing members not to support it. National Union Management could not contain strikes, for they were organized at the grassroots level. The adverse weather conditions and the haulers strike disrupted the British economy, but Prime Minister Callaghan denied that fact. Conversely, Margaret Thatcher acknowledged that the situation was difficult, which led to the Conservative Party’s win against Callaghan in the next elections (Chiripanhura & Wolf, 2019). Thatcher and many conservative leaders such as Boris Johnson used the Winter of Discontent in their campaign manifestos.

Conclusion

The strike activity in the United Kingdom has been radical since the 1970s. Initially, the trade unions were vibrant and successful in all their matters since they were protected nationally and even internationally. As of the 21st century, in the contemporary setting, the UK system of governance has limited the functioning of trade unions and labor movements. Nowadays, industrial actions are low-level and fewer than in previous times in British history. Certainly, trade unions are essential in any labor market, for they protect workers from discrimination and bargain for better working conditions for them; they use strikes as a tool.

References

Armstrong, M. (2018). Strikes in the UK are at an all-time low. Statista. Web.

Chandler, J., Berg, E., & Barry, J. (2018). Workplace stress in the United Kingdom: contextualizing difference. In Work Stress (pp. 33-51). Routledge.

Chiratos, A. (2018). Trade Unions and their role in contemporary society and economy. Kent Law Review, 4. [PDF file]. Web.

Chiripanhura, B., & Wolf, N. (2019). Long-term trends in UK employment: 1861 to 2018. Web.

Cullinane, N. (2018). The field of employment relations: A review. The Routledge Companion to Employment Relations, 23-36.

European Trade Union Institute. (2016). Strikes in the UK: Background summary. Web.

Gall, G., & Kirk, E. (2018). Striking out in a new direction? Strikes and the displacement thesis. Capital & Class, 42(2), 195-203. Web.

International Labour Organization. (2016). Non-standard employment around the world: Understanding challenges, shaping prospects. [PDF file]. Web.

Mangan*, D. (2020). COVID-19 and labor law in the United Kingdom. European Labour Law Journal, 11(3), 332-346. Web.

Miners Strike. [@Miners_Strike]. (2021). #OnThisDay 1984. Tony Benn urges the labour movement to prepare for a general strike to protect free trade unionism, political freedom and civil liberties in Britain. [Tweet]. Twitter. Web.

Office for National Statistics. (2021). Labor market overview, UK: October 2021. Web.

Pohl, N. (2018). Political and economic factors influencing strike activity during the recent economic crisis: A study of the Spanish case between 2002 and 2013. Global Labour Journal, 9(1). Web.

Socialist Equality Party (Britain). [@SEP_Britain]. (2021). Workers face a political fight not only against the Johnson government, but against its political servants in the Labour Party. Mayor Khan and TfL have submitted plans to force more than £1.3 billion in cuts, with tube budgets to be slashed by 9 percent. [Tweet]. Twitter. Web.

Strike Map UK. [@StrikeMapUK]. (2021). Our @unitetheunion members at Hoyer Petralog in Newport have secured an incredible pay deal which exceeds 16% over one year and achieves a wage £17.50 per hour. Well done to all of our members at Hoyer Petralog for remaining united and securing this fantastic win. #UniteWin [Tweet]. Twitter. Web.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D