Introduction

In spite of various cost optimization and effective resource planning/allocation initiatives, the U.S. healthcare system cannot be considered perfect. Coupled with the system’s intrinsic flaws, external finance-related concerns, such as the increasing prevalence of substance abuse, give rise to significant financial challenges to be addressed through appropriate large-scale policy decisions. The purpose of this paper is to explore substance use as a healthcare finance issue, review its significance with regard to healthcare policy, and explain its impacts on the future of healthcare service provision in the U.S.

Substance Abuse Treatment Costs and the Need for ED Visit Prevention Policies

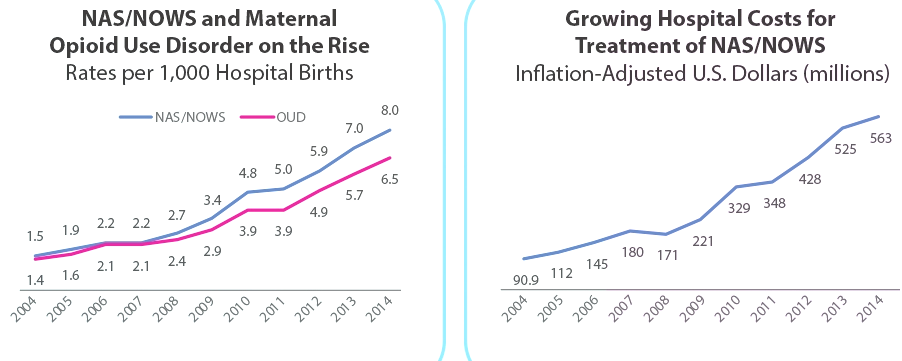

Substance abuse has emerged as a major healthcare finance concern in recent decades, and its financial manifestations incorporate the costs of abstinence-related treatments in various populations. For certain highly addictive drug classes, such as opioids, the recent consumption patterns are of epidemic nature, which leads to the expansion of drug abuse’s economic burden, including the emergence of the youngest service consumers. As Figure 1 indicates, the prevalence of opioid use disorders diagnosed in puerperal populations has been rising since 2004, leading to a six-fold increase in inpatient treatment costs for abstinence and opioid withdrawal syndromes in neonates (NAS/NOWS) between 2004 and 2014. The trend exacerbates the already substantial drug abuse treatment expenses in the U.S.

ICU and ED visits following overdose-related life-threatening conditions also add to substance use disorders’ financial burden, which cannot go unnoticed for policy decisions. In the U.S., ED visits with drug-related conditions as the primary diagnosis have seen a 44% increase since 2006, contributing to enormous healthcare expenses (Peterson et al., 2021). Specifically, as per the nationwide economic analysis of substance abuse ED and hospital encounters, overall direct costs exceeded $13 billion in 2017, including expenses from more than 124 million individual ED visits (Peterson et al., 2021). Illicit drug use is positively correlated with the likelihood of seeking hospitalization or immediate medical attention and initiates a 2.2 times increase in a consumer’s demand for services (Ryan & Rosa, 2020). Considering healthcare resources’ non-unlimited nature, emergencies from overdose events consume a considerable portion of the entire system’s offerings in terms of patient capacity, healthcare personnel’s time, diagnostic services, and pharmaceutical treatments, which creates the need for improvements in substance abuse prevention policies.

Substance abuse epidemics’ unique cost-related patterns highlight the significance of effective abuse prevention policies and early addiction treatment focused on the most “costly” and addictive substances. As per the analysis of healthcare service utilization in Florida between 2016 and 2018, the costs of drug-related admissions and inpatient visits exceeded $2 billion for opioid addiction, followed by $1.3 billion for cocaine users, with nearly a two-fold increase in total costs between 2017 and 2018 (Ryan & Rosa, 2020). Based on data from New York City, unintended overdose events linked with highly addictive substances represent 19% of ICU admissions, resulting in spending a considerable portion of emergency care resources on preventable emergencies (Cervellione et al., 2019). In substance abuse cases, the damage to the body systems’ functionality and the speed of recovery from illness grow progressively, making the prevention of disabling emergency conditions the preferable option both ethically and financially.

Healthcare Policy for Cost Reduction

The ongoing financial issue has prompted various prevention-focused healthcare policy decisions aimed at minimizing the burden on emergency medical services, though their success remains an open question. Six years ago, President Obama signed the Twenty-First Century Cures Act or the Cures Act (Davis, 2019). The Cures Act sought to streamline medication and service development and administration processes and established opioid state targeted response (STR) grant programs to fund innovative anti-crisis measures at the state level (Davis, 2019). Funds from the program have promoted the instrumentalization of the novel ED bridge model in Kentucky to reduce subsequent ED encounters for patients with intravenous drug abuse disorders and link ED service users to recovery and addiction treatment resources without interruptions (High et al., 2020). In Missouri, the program promoted the statewide adoption of the MedFirst addiction treatment program based on low-barrier buprenorphine treatments (High et al., 2020). Despite local care quality improvements, the policies’ actual cost-saving potentials are yet to be explored.

The financial issue, especially patients’ access to addiction treatments, finds reflection in national healthcare policy decisions to redistribute the drug prescription authority. From systematic review research, deficiencies in maintenance treatments’ logistics, including the scarcity of prescribers, could contribute to increased ED service utilization (Hall et al., 2021). The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) and the SUPPORT Act of 2018 aim to prevent resource-consuming healthcare encounters by facilitating access to partial agonist opioids (Davis, 2019). Prior to the acts’ adoption, less than one out of twenty physicians could prescribe buprenorphine products legally, resulting in patients’ lack of access to such treatments in more than half of U.S. rural territories (Davis, 2019). The CARA expands patient caps for physicians and grants some physician assistants and nurse practitioners a temporary right to proceed with buprenorphine prescriptions, and the SUPPORT legislation further reinforces pain management in opioid withdrawal and prevents failed opioid cessation endeavors by making such permissions permanent (Davis, 2019). Thus, policy responses to the opioid crisis’s financial aspects incorporate innovative role clarification processes.

The Issue’s Implications for the Future of Healthcare in the U.S.

Based on the financial issue’s pendency, it is possible to hypothesize two distinct impacts of the ongoing growth of addiction-related service utilization on the future of healthcare service provision in the U.S. Firstly, in the absence of alternatives to addiction prevention strategies, the U.S. healthcare system will continue experimenting with opioid STR grants to discover the generalizable approach to curbing the costs of drug abuse and overdose events for EDs and inpatient settings. Secondly, to address the financial burden of substance abuse on EDs, the healthcare system will continue searching for affordable, cost-lowering, and technology-mediated ways of reaching patients with substance addictions, including telehealth applications for high-risk populations.

The first impact is a natural consequence of the experiments initiated a few years ago. In its recent report to the U.S. Congress, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] (2021) takes an optimistic stance towards state opioid response (SOR) grants and their promise in terms of increasing buprenorphine prescription, patients’ access to pain management, and preventive services’ effectiveness. The agency also expresses the readiness to restore the emphasis on “these life-saving treatments” in the program’s “future iterations” (SAMHSA, 2021, p. 17). This determination stems from preliminary evidence, including SOR grantees’ success in establishing accessible recovery support services for healthcare consumers addicted to both opioids and psychoactive stimulants. Particularly, in SOR grantees’ projects, an 89% decline in consumers seeking ED treatments within the six-month frame makes the grant program’s continuation a crucial opportunity (SAMHSA, 2021). If the same trends are observed in all grantees, the U.S. healthcare system will be capable of translating them into substantial cost savings.

The growing care costs will likely increase the adoption of telehealth technology in abuse, overdose, and neonatal abstinence syndrome prevention. Hard-to-reach opioid users, including female injection drug addicts in rural areas, already benefit from contraceptive counseling delivered via telemedicine, which could prevent subsequent increases in NAS/NOWS and associated care costs (Thompson et al., 2020). With the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. federal agencies have approved the initiation of buprenorphine therapy via virtual and telephone encounters, resulting in the relaxation of telemedicine-related restrictions (Drake et al., 2020). Colorado’s, Hawaii’s, and Louisiana’s experiences with telehealth within the frame of the SOR program suggest its positive effects on treatment retention, which could factor into savings in the future (SAMHSA, 2021). As a promising mode of service delivery for substance abuse prevention and decreasing ED resource utilization, telehealth will probably continue to expand in substance abuse treatment services, promoting the healthcare system’s ongoing digitalization.

Conclusion

To sum up, problematic substance use patterns constitute a healthcare finance issue by increasing healthcare consumers’ demand for inpatient treatment and ED overdose treatment services followed by long-term recovery. The challenge’s tremendous importance as a healthcare policy concern has resulted in state-level grant programs for responders to the opioid crisis and drug prescription authority redistribution initiatives to achieve reductions in ED service costs by emphasizing the prevention of life-threatening drug-related events. The financial concern’s possible implications for the future of healthcare for U.S. consumers are the continuous support of SOR grantees’ innovative drug abuse prevention approaches and telemedicine’s increased adoption.

References

Cervellione, K. L., Shah, A., Patel, M. C., Curiel Duran, L., Ullah, T., & Thurm, C. (2019). Alcohol and drug abuse resource utilization in the ICU. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 13, 1-5. Web.

Davis, C. S. (2019). The SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act – What will it mean for the opioid-overdose crisis? New England Journal of Medicine, 380(1), 3-5. Web.

Drake, C., Yu, J., Lurie, N., Kraemer, K., Polsky, D., & Chaiyachati, K. H. (2020). Policies to improve substance use disorder treatment with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 14(5), 1-5. Web.

Hall, N. Y., Le, L., Majmudar, I., & Mihalopoulos, C. (2021). Barriers to accessing opioid substitution treatment for opioid use disorder: A systematic review from the client perspective. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 1-16. Web.

High, P. M., Marks, K., Robbins, V., Winograd, R., Manocchio, T., Clarke, T., C. Wood, & Stringer, M. (2020). State targeted response to the opioid crisis grants (opioid STR) program: Preliminary findings from two case studies and the national cross-site evaluation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 108, 48-54. Web.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2019). Dramatic increases in maternal opioid use and neonatal abstinence syndrome. Web.

Peterson, C., Li, M., Xu, L., Mikosz, C. A., & Luo, F. (2021). Assessment of annual cost of substance use disorder in US hospitals. JAMA Network Open, 4(3), 1-8. Web.

Ryan, J. L., & Rosa, V. R. (2020). Healthcare cost associations of patients who use illicit drugs in Florida: A retrospective analysis. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 15(1), 1-8. Web.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). 2021 report to Congress on the state opioid response grants (SOR). Web.

Thompson, T. A., Ahrens, K. A., & Coplon, L. (2020). Virtually possible: Using telehealth to bring reproductive health care to women with opioid use disorder in rural Maine. MHealth, 6, 1-11. Web.