Introduction

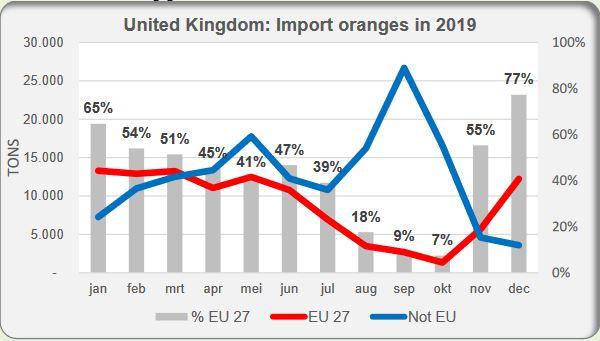

The ability to design and maintain resilient supply chains is one of the key requirements in logistics and distribution to remain prepared for unexpected events and be capable to quickly restoring to normal operations. Particularly, it is important during pandemics, when countries are not affected on the same scale, while the demand for certain food products increases because of lockdowns and restrictions. In the case of Scotland, an example of such a product is oranges, which are supplied by European and non-European countries throughout the year depending on the seasonality trends. Specifically, the imports from the former are more intensive from November to June, while the latter become more frequent from May to October (Fresh Plaza, 2020). However, with a recent government intention to announce a no-tax duty for the citrus products imported from non-European locations, it is required to reconsider essential components of the current supply chain model and elaborate on potential changes.

Based on the above context, the aim of this report is to propose a flexible and resilient supply chain model that ensures the continuous availability of oranges for Scottish consumers, given the constraints imposed by the pandemics. The following objectives are further identified to support this aim:

- To critically analyze the current route-to-market of oranges from main suppliers to Scotland

- To propose a supply chain audit procedure that helps to increase the traceability of oranges to the Scottish food market and propose potential improvements in the end-to-end integration

- To provide recommendations for improving inventory management practices so that oranges are equally available to all customers in Scotland.

Critical Literature Review

In recent studies, many researchers in the supply chain management field explored models and strategies for the distribution of fruits and, particularly, citruses. For instance, Sahebjamnia Goodarzian and Hajiaghaei-Keshteli (2020) proposed a three-echelon model for the citrus distribution network, arguing that one is required to address issues of the limited harvest period, high rates of product perishing, and special requirements for storage and distribution. By three echelons, Sahebjamnia Goodarzian and Hajiaghaei-Keshteli (2020) defined suppliers (for this case, gardeners) as the first network layer, distributors who purchase the product within the planning horizon dependent on the harvesting period as the second layer, and final customers as the third layer. It was also admitted that the distribution layer could be manifested through the sublayers of distributors, which store the unprocessed product from other distributors because of budget limitations and storage constraints. Considerably, the authors found that the harvesting period constraint leads to an increase in the product price for unprocessed citruses, which could be solved by using rental depots, forecasting product flows, and choosing optimal transportation types between the network echelons depending on the customer segmentation and predicted through the application of meta-heuristic algorithms.

The role of optimizing the upstream stages of the product supply chains has been further analyzed by Naseer et al. (2019) based on the case of Pakistan, which is the fifth larger supplier of citruses in the world. Specifically, it was mentioned that sustainable supply chains in agri-food businesses such as citrus exports include farmers as the main actors, while also having a negative effect on downstream actors such as suppliers and customers, further articulating the enormous post-harvest losses of about 40% in Pakistan (Naseer et al., 2019). To verify specific production and marketing constraints, the author conducted 5 group discussions with 41 farmers, overall identifying six groups of constraints related to quality, risk and climate, economic development, knowledge and information, transportation, and poor infrastructure (Naseer et al., 2019). Overall, it is important to note that the most critical constraints on the production level were identified as labor performance issues, mounting input costs, and poor quality of both pesticides and fertilizers, while similar constraints on the marketing level were included a lack of packaging facilities, no quality incentive for fruit size grading and packaging, and perishable product nature.

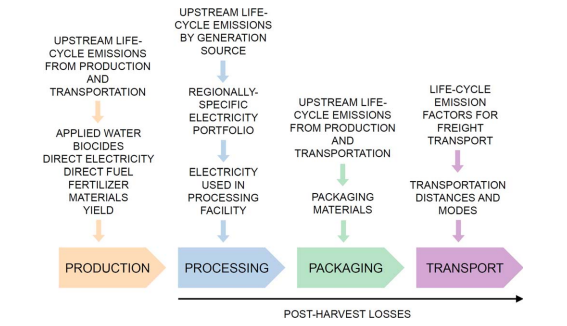

The post-harvest losses issues for the orange supply market were also explored by Bell and Horvath (2020) based on the case of the United States and related environmental impact. Using the conceptual framework shown in Figure 1, the authors outline critical areas that should be considered for designing a sustainable supply chain during the production, processing, packaging, and transportation stages. According to Naseer et al. (2019), the upstream issues are identified as being critical for the post-harvest orange distribution planning. Furthermore, it was found that depending on the transportation mode, distance, and seasonality, oranges shipped in containers from larger distances might have six less times carbon footprint compared to those trucked from nearby countries (Bell and Horvath, 2020). Overall, the authors suggest that a resilient supply chain design for preventing post-harvest losses is dramatically influenced by the electricity portfolios used for citrus processing, types of packaging materials used by suppliers, as well as transportation specifics followed by the distributor.

With respect to the previously mentioned risks and losses for traditional food supply chains, the alternative logistics models were also investigated. For instance, Enjorlas and Aubert (2018) explored the concept of short food supply chains (SFSCs) implemented among French fruit producers. It is argued that SFSCs transcend traditional views on how food is produced, distributed, and purchased taking into consideration the increasing upstream role of farmers, proximity to consumers, as well as cultural or spatial relationship between producers and consumers (Enjorlas and Aubert, 2018). The SFSC model basically builds on the economic, social, and environmental pillars of sustainability, and implies that both indirect and direct sales are required on the side of farmers rather than passively engaging suppliers for product processing, storage, and distribution. It was also admitted that SFSC improves the sustainable behaviors of farmers, who are likely to demonstrate more responsible behaviors in producing fruits through direct sales (Enjorlas and Aubert, 2018). Hence, it is important to note that SFSC could be considered as an alternative mode for European exports of oranges as a parallel strategy for meeting the orange demand and avoiding post-harvesting issues faced by traditional food chains.

Overall, the literature points to the importance of considering all stages of the food supply chain in a single model, where the focus should be made on the upstream elements during production. However, in some cases the focus of the analysis is limited to a specific country, sustainability problem, or business orientation, where major steps in logistics planning such as inventory management are omitted. Hence, it is important to develop a new model that will consider both the economic and sustainability requirements of the Scottish population.

Critical Analysis

Current State

The current state of the UK market of orange consumption demonstrates seasonal dependency from the non-European and European producers and suppliers. Considering that the major non-European suppliers such as South Africa and Egypt operate synchronously by satisfying the demand period from November until June (as shown in Figure 2), the rest of the imports are mostly served by a single European orange supplier, the Spain (Fresh Plaza, 2020). Based on the literature evidence, it means that the majority of non-European route-to-market strategies to supply oranges to the UK are based on using an adjusted three-echelon model of engaging multiple distributors operating either with fresh or processed oranges, eventually exported from the neighbor European countries such as Netherlands (Sahebjamnia, Goodarzian, and Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, 2020). Eventually, it adversely affects pricing decisions related to the choice of transportation modes other than shipping, costs of storage of perishing oranges, and might eventually cause another price increase if orange demand as a source of fresh juice will become a new consumer trend, as recently shown for the case of the US (Heng, Zansler and House, 2020). Hence, it is important to note that the current supply chain state requires certain optimization in terms of supplier strategy and stakeholder engagement.

Best Practices and Benchmarking

Current supply chain theories and models suggest several approaches towards developing the best strategy in food distribution, while for the purposes of supply chain resiliency during times of pandemics it is worth starting from market segmentation. As suggested by Bozarth and Handfield (2016), finding the balance between a number of customers and revenues through the key account selection allows for developing a customer-driven strategy that supports the appropriate product channeling ideas and provides incentives to evaluate customer value to the business. Alternatively, customer opinions and preferences could be used through the market research efforts using surveys of the orange consumption trends, focus groups related to the healthcare culture associated with orange juice based on the seasonality adjustments, as well as direct information gathering through the supply chain stakeholders (Naseer et al., 2019). Innovative models such as SFSC might be also seen as feasible in considering how the market will react to indirect supplies of oranges from neighboring countries such as Spain (Enjorlas and Aubert, 2018). However, it is important to link the above considerations to the principles of customer-centricity and seasonal demand, with both parameters eventually limited by pandemics.

Future State

The future state of the orange export market in the UK is further illustrated in Table 1 using the design principles of Klarjic’s matrix. Overall, given the client’s stance in the UK, it is proposed to leverage on exploring how supplier activities could be synchronized to manage both European and non-European producers at lower costs using a single organization, which would help to set optimal price targets across retailers. Furthermore, it is advised to consider Spanish exports through the SFSC model, which will decrease the engagement of side suppliers in indirect sales, as well as seek exclusivity in supply services based on the previous procurement experience. To the point, it is not critical to formalize agreements with suppliers and propose alternative transportation routes given the potential lockdown restrictions and economic shifts. Nevertheless, it is critical to ensure that orange supply producers are incentivized to sell quality fruits at an affordable price, which is still hardly regulated on the international level.

Figure 2. Klarjic’s matrix for the future state of supplier management.

Gap Analysis

By suggesting the future state of supplying oranges to the UK in the amounts that satisfy the needs of consumers and the capability of supply chains, the following gaps are identified:

- The upstreaming supply chain needs of farmers in remote areas are yet to be designed and aligned on the government level, since, the proposed model is mostly customer-centric and could not be fully realized under the risks of uncertainty;

- The taxation policy for product exports to Scotland is not clear after the Brexit conventions, since there is still no clarity on whether non-European orange producers will be taxed at all or European producers will receive even higher taxation margin because of the economic and epidemiological situation;

- It is hard to evaluate the presence of alternative suppliers given the budget constraints and risks related to current suppliers, as well as the geographical location of Scotland with a profound orientation of water and air transportation.

- Orange as a perishable product is easily substituted with other citruses or fruits that contain necessary vitamins; hence, during pandemics, its demand remains inconsistent.

Building a Roadmap

The suggested roadmap for the supply chain optimization related to oranges availability in Scotland comprises four steps. First, it is advised for the client to conduct robust market research of citrus consumers to understand the demographics of orange consumers and their role in company profitability making. Afterward, it would be possible to derive a better understanding of how customer-centric efforts could be applied to satisfy the specific needs of particular groups in Scottish communities. Second, it is worth conducting a supplier analysis using fishbone diagrams, Pareto analysis, and additional relevant techniques to estimate their contribution to the business and potential select new criteria for selecting alternative vendors and producers in chosen countries (Chopra and Meindl, 2016). Third, it is important to note that the client should liaison with government representatives and financial analysts to estimate further risks for arranging mutual agreements with European and non-European suppliers to ensure that those are in line with expectations from deploying the new logistics model to the business. Finally, the use of risk assessment tools pertinent to the current or similar supply chains in a food industry might be beneficial for the conclusive efforts on orange supply feasibility in economic terms.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Referring to the report’s objectives, the following conclusions were made. First, the current route-to-market of orange supplies to Scotland is stratified, since many producers and distributors operating under the different supply chain models are engaged. It creates issues with managing inventory resources and creating targeted customer engagement strategies, specifically in times of pandemics when supply delivery models become more direct. Second, it was proposed that traceability of product deliveries could be achieved by comparing profit impacts to supply risks; therefore, narrowing down the list of trusted suppliers and eventually searching for ways of implementing SFSC in Spain. As for recommendations, those were majorly described in a roadmap section and imply that the use of both qualitative and quantitative market research tools, as well as risk assessment scenarios, are paramount to search for the most appropriate partnership strategies with suppliers, producers, and customers. However, it is also important to consider the role of government regulations in meeting the citrus export requirements, as well as collaborating toward the upstream supply chain strategies optimization.

Reference List

Bell, E.M. and Horvath, A. (2020) ‘Modeling the carbon footprint of fresh produce: effects of transportation, local ness, and seasonality on US orange markets.’ Environmental Research Letters, 15(3), 034040.

Bozarth, C.C. and Handfield, R.B. (2016) Introduction to operations and supply chain management, 5th ed. Pearson.

Chopra S. and Meindl P. (2016). Supply chain management: strategy, planning, and operation, 6th ed. Pearson.

Enjorlas, G. and Aubert, M. (2018). ‘Short food supply chains and the issue of sustainability: a case study of French fruit producers’. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 46(2), pp. 194-209.

Fresh Plaza (2020) Could Spanish citrus soon fall foul of British import duties?

Heng, Y., Zansler, M. and House, L. (2020) ‘Orange juice consumers response to the Covid-19 outbreak’. EDIS, 4, pp. 1-4. Web.

Naseer, M.A.R., et al. (2019) ‘Critical issues at the upstream level in sustainable supply chain management of agri-food industries: evidence from Pakistan’s citrus industry’. Sustainability, 11(5).

Sahebjamnia, N., Goodarzian, F. and Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. (2020) ‘Optimization of multi-period three-echelon citrus supply chain problem’. Journal of Optimization in Industrial Engineering, 13(1), pp. 39-53. Web.