Introduction

Russia’s economic and social environment is based on a previously populist system, maintained despite growing tensions with Western nations and civil unrest. As no political or economic reforms are expected, there is a need to examine the country’s structure, analyze its economic and noneconomic surroundings, and explore potential prospects for domestic and foreign investment (Economist, 2018). The government currently ranks first in the world in terms of natural gas and crude oil output. Its considerable power is due to the decisions it has taken about energy security. A powerful Russia is admired and appreciated both locally and abroad. That is what Russia aimed for when it developed an energy security policy. It elevates Russia to the same level as any other foreign country. The presented technology was concerned with pumping more oil at a cheaper cost. Its political strength was dubious, and the economy was weak, but that was the risk it had to take to become as powerful as it is now.

Furthermore, Russia is a vast, cold area populated by several ethnic groups that historically clashed with Moscow’s combined authority. This leaves Russia with a legitimate set of priorities to keep the country together and secure its position as a provincial force. To begin, Russia must unite its people around a single power (Economist, 2018). Second, it must focus its energy on its immediate surroundings to create cradles against opposing forces. The establishment of the Soviet Union is the most obvious example of this fundamental in real life. Finally, it must use its unique assets to achieve a balance with the vast powers beyond its borders. This paper aims to provide a thorough and insightful analysis of Russia’s energy policy and suggest recommendations for the country to remain naturally prowess.

Energy Sector Background in Russia

The Russian Energy approach is documented in an Energy staggering policy archive, which outlines policy until 2020. The Russian government approved the essential purchases of the Russian energy procedure until 2020 in 2000, and the legislature approved the new Russian energy system in 2003. The Energy Strategy report highlights a few significant needs: increased energy productivity, reduced environmental impact, practicable improvement, energy progression and technological development, and improved viability and competitiveness. State control of the venture and open responsibilities for resources were used to define the economy. (Rousseau, 2018) The Soviet Union’s economy was based on an arrangement of state responsibility for approach for creation, aggregating cultivating, contemporary assembling, and combined authoritative arranging. The focus on identifying and analyzing Russia’s strategy, context, and performance is the best way to develop an analysis of its current status and impact on its national economic environment. Though various aspects within each of these components contribute to the outlook of the country’s framework, the most distinguishing feature of each is an awareness of the contemporary situation.

Historical Perspectives

Political Background

The Putin administration is well aware of the issues surrounding Russia’s energy sector. Russia’s efforts in the previous decade to wean itself off of dependency on energy markets by focusing on mechanical development have been largely ineffective. The country remains preoccupied with the fate of its energy sector. Russia’s policy of leveraging its energy transactions as both an exterior strategy tool and a revenue generator is occasionally contradictory: To use energy remotely, Moscow must be able to lower or raise costs and debilitate to cut off supplies, which is an obscenity from a revenue standpoint. The Kremlin has begun developing policies to adapt the country to the changes that will occur over the next two decades (Henderson & Moe, 2019). With such tactics, Russia may raise its power generation levels to a far higher level than now.

Economic Background

The Soviet financial system was designed to last for at least six decades, and parts of it remained in place when the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991. The pioneers who had the most significant impact on that framework were its organizer, Lenin, and his successor Stalin, who secured the most prominent examples of collectivization and industrialization that had to be standard of the Soviet Union’s halfway-arranged framework. In the year 1980, on the other hand, as the national economy lagged, inherent flaws had to be exposed; without further ado, change programs began to remodel the traditional framework. Yeltsin, one of the late 1980s’ boss reformers, oversaw the significant collapse of the central arranging framework in the mid-1990s (Henderson & Moe, 2019). While Russia had supply shortages in the 1980s, Russians could not regulate the cost of most things throughout the 1990s as imported goods poured into the country. Stores that had previously been empty were now stocked with many things that no one could bear to buy (Phyllis, 2021). The soviet system was being organized by elected pioneers who had the most significant impact on the energy policy that was later adopted.

Energy Background

Russia was a naturally impoverished nation, surrounded by other great countries and with no flawless borders. Furthermore, Russia is a gigantic, largely ungrateful country populated by several ethnic groups that have consistently clashed with Moscow’s combined power. This leaves Russia with a specific set of goals to keep together as a nation and establish itself as a local force. To begin, Russia must unite its people under a single power. Second, it must spread its energy across its immediate surroundings to provide buffers against various forces. The Soviet Union’s output is the clearest example of this fundamental in real life. Finally, it must persuade its shared assets to achieve parity with the significant powers beyond its borders. Throughout history, Russia has used a variety of tools to accomplish these goals, ranging from farming fares to flawless military success and intimidation (Rousseau, 2018). By the 1950s, Russia’s oil sector had become one of the country’s most important financial and political pillars.

A framework of Analysis: Strategy, Context, and Performance

The Russian Energy approach is documented in an Energy staggering policy archive, which outlines policy until 2020. The Russian government approved the essential purchases of the Russian energy procedure until 2020 in 2000, and the legislature approved the new Russian energy system in 2003. The Energy Strategy report highlights a few significant needs: increased energy productivity, reduced environmental impact, practicable improvement, energy progression and technological development, and improved viability and competitiveness. State control of the venture and open responsibilities for resources were used to define the economy. The focus on identifying and analyzing Russia’s strategy, context, and performance is the best way to develop an analysis of its current status and impact on its national economic environment. Though various aspects within each of these components contribute to the outlook of the country’s framework, the most distinguishing feature of each is an awareness of the contemporary situation.

Strategy

In 2015, falling oil prices combined with tight fiscal policy contributed to Russia’s economy entering a significant recession, which peaked in the second quarter of 2015. To strategy, Russia has concentrated on revising essential fiscal policy items in the future. Russia is bolstering its non-oil revenue base to compensate for decreased oil and gas revenues, which have fallen in lockstep with oil prices (World Bank, 2018). Furthermore, Russia established the Renewable Energy Program, which will aid in growing private sector participation in renewable energy. The program, funded by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), aims to enhance Russia’s policymakers’ global recognition that expanded energy efficiency and renewable energy technology usage can help sustain increased demand for energy resources (IFC, 2017). With the established Renewable Energy Program, Russia realized a boosted participation of both public and private sectors in renewable energy.

This policy includes the country’s ambitions to implement a green tariff for domestic renewable energy producers. The tax will be offered to domestic and foreign enterprises seeking to invest in developing facilities on the country’s territory (Gerden, 2018). In conjunction with the overall policy for a renewable energy strategy, Russia is built on attracting domestic investment and foreign country entrants such as Tesla to help construct an updated national business environment.

Context

As Russia attempts to recover from its 2015 economic crisis, much of its progress has been slowed by unfavorable external conditions and international sanctions. The consequences have continued to reduce domestic poverty rates while discouraging future global investment. According to the World Bank, Russia’s economic outlook appears to be biased to the worst with the previously mentioned variables (World Bank, 2018). Nonetheless, the dire economic environment has provided Russia with an opportunity to shift its traditional industry of exporting raw commodities to being competitive globally in more premium technologies such as renewable energy technology. Other domestic and international firms will be able to invest in Russia’s new plans and help its economic transition due to the change.

Performance

As previously stated, Russia’s economy underwent a severe downturn in the second quarter of 2015. As Russia attempts to recover from its 2015 economic crisis, much of its progress has been slowed by unfavorable external conditions and international sanctions (World Bank, 2018). The consequences have continued to reduce domestic poverty rates while discouraging future global investment. Coupled with the deteriorating economic environment caused by the drop in oil prices, Russia’s economy suffered a dramatic reduction in income, sapping customer demand and deterring investment (World Bank, 2018). These factors conspired to cause a sharp depreciation of Russia’s currency, the ruble. Currency devaluation has a negative impact on inflation; in Russia’s instance, the economy saw a double-digit increase (World Bank, 2018). Household purchasing power fell as a result of the snowball effect, the pace of monetary easing slowed, and consumer demand plunged.

Energy Sources and Market Dynamics Impacts in Russia

Russia has long been focused on the European markets. Since then, they have been overly convinced that they rule the European markets. Several new projects are being created; however, these recent efforts may balance falling yield from aging fields and not result in essential yield development in the near term. The usage of more advanced technologies and the employment of improved recuperation systems are resulting in increased oil production from current oil stocks (Makarov, 2020). With the focus on the European market for their energy, Russia has captured a substantial global market, thus raising its GDP.

The potential oil reserves of Eastern Siberia, the Russian Arctic, the northern Caspian Sea, and Sakhalin Island are all vying for attention. Various international oil companies have purchased a property and are investing heavily in research and development on Sakhalin Island’s hydrocarbon-rich. This happens despite the Russian government pushing for a more significant role for domestic companies in these operations. Gazprom acquired ownership of the Sakhalin project from Shell. It is attempting to get control of the displaying of gas supplies from the Sakhalin I anticipate driven by Exxon Neft Ltd, an Exxon subsidiary (Makarov, 2020). Russian firms are also expanding into the Arctic and Eastern Siberian regions, propelled by assessment events and decreasing oil fare levies. While a few new fields have gone online since 2009, putting other areas into production would need substantial investment and may necessitate a changed oil charge administration from the legislature (Makarov, 2020). This will finally result in high profits realized from the energy sector, thus improving the nation’s income.

International Oil (Energy) Companies and National Oil (Energy) Companies

Naturally, Russians control the Gazprom Company, one of the largest petroleum and energy suppliers in the Russian market and adjacent Europe and eastern Russia. Gazprom is a global energy company. Its primary business areas include geographical exploration, production, transportation, stockpiling, preparation, and marketing of gas, gas condensate, and oil, and gas as a car fuel (Gazprom Neft Press Office 2019). It also generates and markets heat and electricity. Gazprom’s primary objective is to provide purchasers with a stable, efficient, and adjusted supply of ordinary gas, other energy assets, and their subsidiaries. The Company’s offer in global and Russian gas outlets accounts for 18 and 72 cents on the dollar, respectively. Gazprom accounts for between 14 and 74 cents of international and Russian gas production, respectively (Gazprom Neft Press Office, 2019). At the moment, the company successfully executes large-scale operations aimed at exploiting gas reserves in the Yamal Peninsula, Arctic Shelf, Eastern Siberia, and the Far East, and its hydrocarbons exploration and generation also extend internationally (Gazprom Neft Press Office, 2019). Being the world’s largest supplier of ordinary gas, Gazprom has enabled Russia to remain an international leader in the energy production sector.

Additionally, Rosneft, Surgutneftegaz, Tatneft, and Lukoil companies dominate the Russian local market. These are state-owned monopoly Transneft, with the subsidiary Transnefte product owning and operating the oil products pipelines. Russia demonstrates the contrast between the attraction of an infinite hydrocarbon asset base for significant oil and gas companies and the difficulties associated with seeking to invest in it. Global Partnership in Russia sheds new light on the collaborative ventures formed between domestic and international partners in Russia during the post-Soviet era. Such partnerships with other international and domestic companies have enabled these organizations to dominate the energy sector despite the political instability within the Russian administration.

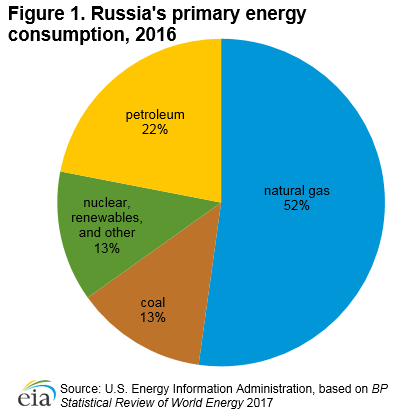

Energy Mix and Changes over Time

Russia is the world’s second-largest producer of regular dry gas and the third largest global producer of fluid fills. Regardless of its significant coal reserves, it supplies a small amount of coal in the world’s market. Russia’s economy is highly dependent on hydrocarbons, with oil and gas revenues accounting for more than half of government spending (Henderson & Moe, 2019). Russia is a significant producer and exporter of oil and natural gas, and its economy is primarily based on energy commerce. Russia’s monetary development continues to be fueled by energy prices, owing to the country’s significant oil and gas production and increased expenses for such items. In 2012, oil and gas revenues accounted for 52% of government spending plans and more than 70% of aggregate fares (Henderson & Moe, 2019). Russia is the world’s third-largest generator of atomic energy and fourth-largest in terms of introduced limits. According to the IAEA, Russia is currently developing 10 nuclear reactors, placing it second on the globe in terms of reactors under development in 2012 (Henderson & Moe, 2019). Being a world leader in energy production, Russia has realized significant outputs from energy production, thus boosting other sectors of the economy such as education, transportation, and agriculture sectors.

Energy Security Challenges

Energy security challenges are all connected to Russia’s ties with the European Union, which are strained as a result of Russia’s economic sanctions. Correspondence in energy business access is a problem that has consistently been addressed at the highest level of the EU-Russia strategy throughout time. After a while, the topic has grown to imply something different to each side of the association. Correspondence for the EU pertains to the openness of the internal energy market in exchange for access to remote markets (Aron, 2019). Correspondence also considers the insurance of the internal business against those states that have not altered their energy sectors in comparable amounts. In any event, Russia finds a correlation with the condition of the long-distance supply management that exists in the global gas exchange. It is more adept at bargaining through quantitative exchanges such as ‘volumes by volumes’ or asset swaps.

Simultaneously, venture correspondence stems from any political agreement between the on-screen actors. Fundamentally, the issue is best expressed through, on the one hand, the tenets governing third-country administrators within the EU’s internal energy market contained in the ‘third legislative Market Package,’ and on the other hand, the repeal of existing and the adoption of new Russian legislation governing the support of external organizations within its energy sector (Aron, 2019). The European Commission presented a package of proposals in 2007 to alter the inward energy market. The package comprised firm precepts on the separation of systems from production and supply activities and a correspondence provision.

Energy and Economic Development in Russia

The rapid test of standard gas rentals, on the other hand, is a sharp loss of advantage in the face of resistance from alternative generating techniques made possible by technological advancements. The latter utilizes “even piercing” to access shallow yet expanding reservoirs and water-powered breaking, in which sand, chemicals, and water, gel, or condensed gasses are infused into shale rock formations under extraordinary pressure to concentrate gas and oil (Economist, 2018). As a result, US gas imports have decreased by 45 percent over the last decade. Much more than Russian oil, regular gas rentals are at risk of disappearing entirely in the following years. Despite Gazprom’s famed pollution, its worldwide openness has ranked it as one of the least transparent organizations on the earth.

Putin’s commitment to oil and gas as the backbone of Russia’s development arises from a solid and enduring sense of the industry’s importance to the country’s economy. Much sooner than he came into office, Putin agreed that “restoring the Russian economic growth on the basis of mineral and crude material assets” was “a critical element of near-term economic development” (Economist, 2018). As one of the world’s most powerful oil producers and the primary supplier of unleaded gasoline to Europe, Russia has gradually used its energy revenues to bolster the Putin government. Russia has to minimize its reliance on advantages from these assets as new, less costly energy providers emerge and the industry becomes leaner and more aggressive in order to avoid stagnation and maybe a monetary crisis (Goodrich & Lanthemann, 2020). The administration must implement significant institutional reforms to improve the investment climate and boost the economy, but in doing so, it risks undercutting the tyrannical vertical of force.

Governance on Energy Issues

Ultimately, the EU’s plan to airlift a large amount of distinctive gas from another source is unsustainable. On the basis of current figures, and more precisely, it can be assumed that, even with the inclusion of Azerbaijani characteristic gas, shale gas in North America, and standard gas that can be imported from the Eastern Mediterranean, they will receive less than 50 billion cubic meters, or the aggregate utilization annually. Currently, the volume of gas produced by all of these other sources accounts for less than a third of the natural gas that the US purchases in Russia and less than 10% of total use in Europe. Second, by 2035, the combined use of imported and domestic gas in Europe will increase from 66 percent to 84 percent (Goodrich & Lanthemann, 2020). If these figures are broken down in light of the diminished North Sea inventories, the European Company is risky. Europe is not setting the pace for the probes. Thirdly, Iraq and Libya are defined by their internal turmoil, which extends beyond the energy sector.

Sustainability Issues Related to Energy Policies and Quest for Justice

Energy’s usefulness as a means of achieving Russia’s three primary aims has shifted throughout time as Russia has been forced to adapt its approaches in response to changes in domestic or global conditions. Moscow’s strength is in its versatility when it comes to dealing with its energy sector. The energy division has contributed to the construction of a locally stable and technological state in the past (Phyllis, 2021). Russia’s household energy consumption is high due to the country’s generally cold climate for a large portion of the year, but despite inefficiencies in the energy sector and the high cost of producing energy, the country’s residential stores have enabled Moscow to provide low energy costs to its subjects and businesses that utilize them.

Recommendations for Foreign Entrants depending on Energy Sector

According to Russia’s economic structure and their priority on their renewable energy project, Tesla is a foreign entrant corporation that will benefit from the improvements and advancements realized. Due to Russia’s declining currency, harsh winter weather unsuitable for electric vehicles, and deteriorating salaries, my proposal would be for Tesla to establish manufacturing operations in more economically viable locations of the nation, such as Moscow. The city has already incorporated multiple electric vehicles charging stations, accounts for the bulk of electric vehicle dealership sales, and is home to the country’s wealthiest customers (Bazenkova, 2017). When the renewable energy policy reaches its full potential, manufacturing under the correct economic conditions and taking advantage of government subsidies would position Tesla as a critical participant in the nation’s commercial climate.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the energy sector boosts Russia’s opportunity to augment its influence among its immediate neighboring countries. Russia’s market economy was restructured in the early 1990s following the collapse of communism, and the result was a deteriorating national business climate. Russia is taking an innovative strategy in the aftermath of the country’s current economic slump, which began in early 2015. Moscow’s use of energy to exert influence on support states varies from every nation and extends beyond controlling local energy output. Switching to alternative oil and gas trading nations may provide a short- to a medium-term solution. However, Europe’s concentration on reducing its reliance on Russia diverts attention away from the region’s constant need for hydrocarbons. While the southern Gas Corridor would avoid Russia and Iran, all indications are that Europe would remain disproportionately vulnerable to hydrocarbon energy exchanges. This situation emanates from a region that would stay under Russia’s area of power, although to a smaller level than formerly.

Rather than prioritizing energy security in terms of the price and import of oil and gas, the ultimate fate of energy security for Russia rests in the growth of energy assets and a shift away from fossil fuel dependency. The government is detaching itself from the old oil business and promoting investments in renewable energy and technology. When combined with the trade benefits and fiscal policy framework that favors local and international investment in this sector, the signals point to Russia benefiting from an increase in consumer and corporate confidence and the reduction of the sensitivity to oil prices that triggered the downturn. The plan establishes a stable future business climate for the country and fosters long-term product development.

References

Aron, L. (2019). The political economy of Russian oil and gas. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

Bazenkova, Anastasia. (2017). Russian Gas Stations Ordered to Provide Chargers for Electric Cars. The Moscow Times. Web.

Gazprom Neft Press Office. (2019). Gazprom Neft Makes First Winter Shipment of Oil from Yamal [Press release]. Web.

Gerden, Eugene. (2018). Russian government to introduce a green tariff for renewables in 2017. Russian Direct. Web.

Goodrich, L., & Lanthemann, M. (2020). The past, present, and future of Russian energy strategy. Geopolitical Weekly, 45(7), 103–108. Web.

Henderson, J., & Moe, A. (2019). The Globalization of Russian Gas: Political and Commercial Catalysts. Edward Elgar Publishing.

IFC. (2017). Russian Renewable Energy Program. Web.

Makarov, A. A. (2020). Technological progress opportunities in the energy sector of Russia. Studies on Russian Economic Development, 31(1), 52-63. Web.

Phyllis, A. (2021). Assessing national energy sustainability using multiple criteria decision analysis. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 28(1), 18-35.

Rousseau, R. (2018). The Russia-China Relationship and the Russian Far East. Web.

The Economist. (2018). Intelligence Unit. Web.

World Bank. (2016). Russian Federation Partnership: Country Program Snapshot. Web.